Unnoticed by much of the public, the Bush administration and the Republican-controlled Congress have been laying the groundwork for a repeal of abortion rights. The effort to ban late-term abortion was just the beginning — anti-abortion activists expect the president to sign several landmark pieces of pro-life legislation next year. Meanwhile, in the wake of the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban, John Ashcroft ordered the Justice Department’s civil rights division — attorneys responsible for prosecuting anti-abortion terrorism, among other crimes — to go after doctors performing late-term abortions, a move that sources inside and outside of the Justice Department say is meant to endow the fetuses with civil rights. Abroad, unfettered by domestic scrutiny, the Bush administration has slashed away at funding for family planning programs that have failed to renounce the mere mention of abortion.

Even as Bush placates moderates by saying that the country isn’t yet ready for a total abortion ban, he’s doing his best to prepare for that eventuality. And except for committed pro-choice activists, American women aren’t mounting much of a defense. Roe vs. Wade might stand a while longer, but it’s being hollowed out, termite style. Another Bush term augurs its eventual collapse.

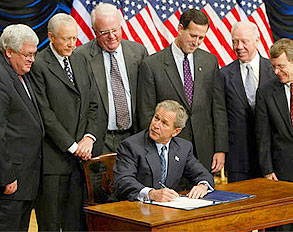

Backed by a crescent of beaming congressmen, Bush signed the Partial Birth Abortion Ban on Nov. 5, marking the first time since Roe vs. Wade was decided in 1973 that the government has outlawed an abortion procedure. According to Cynthia Gorney, a University of California at Berkeley professor of journalism and author of “Articles of Faith: A Frontline History of the Abortion Wars,” the ban was “the biggest victory that the abortion opponents have had in a long time,” and the fruit of a strategy that began even before Roe vs. Wade.

Just hours after the ban’s passage, though, three separate courts enjoined the federal government from prosecuting it, and it will likely take years for it to work its way through the appeals process. For the time being, then, abortion is unlikely to command much public attention, even as Republicans push a host of other anti-abortion legislation, federal appointments and policy.

That’s just how the anti-abortion movement wants it. “People really don’t imagine that Roe could be overturned, and anti-choice groups continually try to reinforce that sort of complacency,” says Susanne Martinez, vice president for public policy at Planned Parenthood. The anti-abortion movement is making tremendous progress, she says, but “they’re doing it below the radar.”

The anti-abortion movement has grown savvy, chipping away at the margins of reproductive rights, laying siege to their foundations, but leaving the edifice apparently intact. None of the anti-abortion measures being pushed by the Bush administration is in itself significant enough to stir the public, and many, such as the Partial Birth Abortion Ban, have wide public support. Yet they add up to an attack on a right that a generation of women has taken for granted.

This is a source of profound frustration to pro-choice activists, who see the rights they cherish slipping away with hardly any public outcry. An April 7 survey commissioned by the Center for the Advancement of Women, a feminist group, found that only 41 percent of women see keeping abortion legal as a top priority for the women’s movement. Activists, then, are in a difficult position: They’re trying to warn quiescent American women, many of them pro-choice but morally uneasy about abortion, that their rights are being eroded. But so far, they can point to no specific rights that actually have been lost.

Right now, several bills that would either curtail abortion or confer personhood on fetuses are wending their way through Congress. Laci and Conner’s Law, also known as the Unborn Victims of Violence Act, will punish attacks on a fetus separately from attacks on a pregnant woman. (It’s named after Laci Peterson, the murdered California woman, and her unborn son, Conner. Whenever possible, Republicans title their legislation after high-profile victims.) When a pregnant woman is attacked, “the pro-life movement says there is a second victim, therefore there should be two victims recognized as being murdered,” says Jim Backlin, director of legislative affairs for the Christian Coalition.

Laci and Conner’s Law has 133 co-sponsors in the House and is expected to be signed into law next year. “There’s momentum behind it,” says Backlin. “Realistically, it will probably pass in the spring of next year, definitely before the election.”

According to the text of the bill, it is meant “to protect unborn children from assault and murder” and applies at “any stage of development.” Though it makes an explicit exception for abortion, within the rhetoric of a law that defines killing a fetus as murder the exception seems absurd — and that’s precisely the point.

Meanwhile, even as attorneys for pro-choice organizations were in court to block the Partial Birth Abortion Ban on Nov. 5, Reps. Jim DeMint, R-S.C., and Roscoe Bartlett, R-Md., introduced a bill to suspend the FDA’s approval of RU-486, the abortion pill. They’re calling the bill “Holly’s law,” after Holly Patterson, an 18-year-old who died in September, a week after taking the pill, making her the second American woman to die from RU-486 complications. In comparison, according to the Food and Drug Administration, as of 1998, 130 Americans died after taking Viagra.

Accusing the Clinton-era FDA of “questionable” practices in approving the drug, Bartlett said, “RU-486 is unrelated to healthcare and anyone who prescribes or administers it shouldn’t be described as a healthcare worker. RU-486 is designed to kill a healthy baby. Now, we know that it kills healthy women such as 18-year-old Holly Patterson who was barely the age of majority and still living with her parents.”

Also high on the anti-abortion lobby’s agenda is the Child Custody Protection Act, which would punish any adult accompanying a minor across state lines for an abortion. It’s meant to stop minors who live in one of the 33 states that mandate parental notification from circumventing those laws by having their abortions in more lenient states. Under the law, anyone who takes a girl to another state for an abortion, including an older sister, aunt or grandmother, is liable to be fined $100,000 and sentenced to up to a year in prison, and may also face civil penalties. The bill, a priority of the anti-abortion movement at least since the Clinton administration, has the White House’s endorsement.

Meanwhile, statewide restrictions on abortion keep multiplying. These include parental involvement laws, mandatory waiting periods and costly regulations governing everything from the landscaping on clinic lawns to the temperature air conditioners must be set to. When challenged, these laws are reviewed by Federal Appeals Courts, which Bush is stacking with zealously anti-abortion judges.

Abroad, assaults on reproductive rights have been even more profound. Bush last year cut funding for the United Nations Population Fund based on the allegations of a radical anti-abortion fringe group that the fund was involved with coerced abortions in China, allegations that an investigative team sent by his own administration found to be false. The freeze on American aid led to cutbacks in reproductive health services worldwide, from Vietnam to Bangladesh to Kenya.

Even more devastating has been Bush’s reinstatement of the Global Gag Rule, which denies American aid to family planning agencies that even mention to pregnant women that abortion is an option. A recent study by Planned Parenthood, Population Action International, and Ipas, an organization that promotes safe abortion worldwide, documented health clinics throughout Africa that have been forced to shut down as a result of the rule. AIDS prevention has also been curtailed. For example, Lesotho, the nation in Southern Africa where a quarter of all women are HIV positive, no longer receives condoms from America because of its government’s refusal to abide by the Gag Rule.

To many experts in abortion politics, the international impact of Bush’s abortion policy may foreshadow what’s to come in the U.S. But thus far, most women in the U.S. haven’t really lost any of the abortion rights they had at the start of the Bush administration three years ago. “Most of the very clear hardships have been internationally,” says Martinez, at Planned Parenthood. “In the United States, it’s harder to document. I think that’s intentional. They’re working on the margins, trying not to play their full hand yet.” If Bush is reelected, though, Martinez and others expect him to become much more aggressive.

Yet if Americans aren’t rising up to oppose Bush’s anti-abortion agenda, it isn’t simply because they’re unaware of it. Even if most Americans are pro-choice, studies show they remain morally conflicted about abortion. They support mandatory parental involvement and restrictions on late-term procedures and oppose government funding for abortion. The Center for the Advancement of Women poll shows that while only 17 percent of women want to ban abortion, half believe it should be more strictly limited. “The reason there’s not a groundswell on the incremental stuff is that so far the incremental stuff is actually acceptable to most people,” says Cynthia Gorney.

As Slate columnist William Saletan writes in his recent book “Bearing Right: How Conservatives Won the Abortion War,” “The people who hold the balance of power in the abortion debate are those who favor tradition, family, and property. The philosophy that has prevailed — in favor of legal abortion, in favor of parents’ authority over their children’s abortions, against the spending of tax money for abortions — is their philosophy.”

The Partial Birth Abortion Ban, after all, may have been part of a long-term right-wing strategy, but it garnered bipartisan support, passing the Senate 64-33. An alternate proposal that included exceptions for the health of the mother was voted down 60-38. “Partial-birth” abortion is a political, not medical, term, and describes abortions performed at any stage of gestation in which the live fetus is partly extracted and then killed outside the woman’s body. The bill described the procedure as “gruesome and inhumane,” a description that much of the public agrees with.

“Why is this not causing more uproar? Because most people who have read an account of what intact dilation and extraction or partial birth abortion actually is are too appalled by it to be able to articulate any kind of defense,” says Gorney. “I’m sure they [pro-choice activists] are really grappling with the best way to address this ban. This is a very hard argument to take before the American people, because they know the American people can’t stand this procedure.”

Contrary to right-wing rhetoric, the ban doesn’t just outlaw third-trimester abortions. It’s worded so as to apply to second-trimester abortions, too. “If you look at the language of the bill, the term ‘partial birth’ refers not to the fact that it’s a nine-month-old fetus. It refers to this method where sometimes part of the fetus is outside the woman’s body,” says Gorney. According to Heather Boonstra, a senior public policy associate at the Alan Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive rights think tank, the law’s language means it may encompass dilation and evacuation, or D&E, a common type of second-trimester abortion.

In one sense, all this might not matter, since most experts think the law is unlikely to pass Supreme Court muster — unless Bush has a chance to replace a pro-choice justice with one who opposes abortion. In 2000’s Stenberg vs. Carhart case, the court struck down a Nebraska Partial Birth Abortion Ban because it didn’t provide exceptions for the health of the mother and didn’t contain a precise definition of the procedure it purported to ban — a crucial point because “partial birth abortion” is not a medical term. The law Bush just signed has identical flaws.

Judie Brown, president of the hard-line American Life League, didn’t support the ban because she felt it didn’t go far enough, and she doesn’t expect it to ever take effect. “We predicted it would be held unconstitutional from the beginning because of vagueness,” she says. “The court has already spoken on that.”

Yet Gorney says that even if the law is never enforced, it still represents an anti-abortion victory. “They have been trying since before 1973” — the year Roe vs. Wade was decided — “to outlaw methods of abortion on the theory that, No. 1, it would at least limit the number that were done, and No. 2, if you could outlaw a nasty method of abortion, you had a public relations vehicle for confronting Americans with how abortion is actually done,” she says. “It is the pro-life view that if you can force people to really look at and think about how abortions are performed, they won’t be able to stomach it, no matter how much they think it should be legal.”

In that, abortion opponents have succeeded. With the Partial Birth Abortion Ban, “what they’ve done is to get a public legislative body to say this is too disgusting,” says Gorney. “The big secret about all this is if this thing stands up, it means there are certain forms of abortion that we think are too disgusting to be legal. If you buy that argument, you’ve basically gotten rid of abortion down to about 14 weeks. If you have a problem with pulling out an intact fetus that has been suctioned by the brain, you’re going to have a bigger problem with pulling out arms and legs that aren’t attached to anything,” she says, noting that dismemberment is commonly used in second-trimester abortions.

Indeed, right now much of the pro-life strategy is focused on changing the way people think about abortion. Some of that happens largely outside the law, through things like clinics and pregnancy crisis centers, anti-abortion organizations that disguise themselves as health clinics. But within the law, opponents of legal abortion are using a variety of subtle measures to create legal and rhetorical recognition of fetal personhood, which they hope will in turn undermine Roe.

Attorney General John Ashcroft demonstrated this immediately after the Partial Birth Abortion Ban was passed. At 11:40 a.m. on the day Bush signed the law, the Justice Department’s entire civil rights office was called into what a Justice Department source describes as a highly unusual meeting. There, civil rights attorneys — who ordinarily prosecute offenses like hate crimes, racial harassment and anti-abortion terrorism — were told they would be in charge of prosecuting the doctors thought to be in violation of the new abortion ban.

To an outsider, the question of which division prosecutes a law might seem like a minor bureaucratic detail, but it would have had two immediate consequences. First, it would have impeded the efforts of career civil rights lawyers to prosecute crimes against clinics and doctors by abortion opponents. According to the Justice Department source, merely by accusing those same doctors of violating the Partial Birth Abortion Ban, anti-abortion activists could force prosecutors to turn around and investigate the very victims they’d set out to protect.

Even more important, though, Ashcroft’s move was meant to frame partial-birth abortion as a violation of a fetus’ civil rights. And if a fetus is endowed with civil rights, abortion itself becomes legally and philosophically untenable.

This is also the logic behind measures like Laci and Conner’s Law. Abortion opponents, says Martinez, are “trying piece by piece to create fetal personhood that they can use to argue that Roe was wrongly decided because a fetus is a person entitled to all the rights of a person.”

The genius of some of these measures is that they actually benefit individual pregnant women. Last year, the Department of Health and Human Services amended the State Children’s Health Insurance Program to cover fetuses, but not the women who carry them. It was a fairly transparent attempt to give fetuses rights independent of their mothers, but it left pro-choice advocates in the uncomfortable position of advocating against a law that would at least indirectly provide prenatal care to women who might not otherwise have it.

“Each individual item is hard to deal with,” Martinez says of these initiatives. “They don’t lend themselves to being seen as part of an overarching agenda, but in each case there is always a better way to do what they’re trying to do.”

For example, with the government health insurance program, “the easy solution would have been to declare pregnant women eligible,” says Martinez. “By making it just the fetus, it left women out. They actually debated whether pain medication during delivery would be covered, because it would benefit the woman, not the fetus. In the end they said it would be allowed because if labor was prolonged because of pain to the women, the fetus might be injured. This is treating the woman like she was a vessel.”

Similarly, she says, when the Laci Peterson law was being debated, pro-choice lawmakers offered legislation to increase penalties for injury to a pregnant women. “They rejected that,” says Martinez. “They’re not interested in protecting a woman who is beaten and killed. They’re only interested in elevating the fetus.”

Anti-abortion activists don’t wholly disagree. “From our perspective, until the majority of Americans see abortion as the killing of a child, we are not going to substantively change things,” says Brown.

Indeed, very few people believe that there is a national abortion ban in America’s immediate future. That doesn’t mean, though, that Roe vs. Wade is secure. If Bush is reelected and has the opportunity to appoint a new Supreme Court justice, the court will have an anti-abortion majority, and the precedent will likely be doomed.

If Roe vs. Wade is overturned, abortion won’t become illegal everywhere — it will be up to individual states. Middle-class women on the coast will continue to have access to reproductive care, much as they did before Roe. Women in conservative states who can afford to travel will also be able to get abortions. Other women with unwanted pregnancies will be out of luck.

In many ways, though, they already are. The combined threats of terrorism, harassment and onerous government regulation has driven many clinics out of business. According to the National Abortion Federation, 97 percent of non-urban counties don’t have an abortion provider. In Texas, there’s no abortion clinic north of Dallas. Nor are reproductive health clinics welcome in other parts of the state. David Morris reported in AlterNet that when Planned Parenthood hired a construction company to build a clinic in Austin, a right-wing coalition organized the Austin Area Pro-Life Concrete Contractors and Suppliers Association, which boycotted the builder. “The Association’s boycott of the project achieved complete success,” Morris wrote. “Every concrete supplier within 60 miles of Austin refused to supply materials. Construction stopped.”

Are abortion rights imperiled, then? “If you live in [a conservative] state and you regard having to drive a very long way to get to the nearest provider as a threat to your health, then yes,” says Gorney. “But that’s been true for a long time.”

Yet it’s also clear that the architects of these policies have in mind much more than the perpetuation of the status quo, or even a return to the pre-Roe days when abortion legislation was left to the states.

In 1996, 45 leading conservatives signed a document called “The America We Seek: A Statement of Pro-Life Principle and concern.” Among the signatories were Michael McConnell, one of Bush’s federal appeals court nominees, former Christian Coalition executive director Ralph Reed, and neoconservative intellectual William Kristol. The statement laid out their hope of eventually amending the Constitution to outlaw abortion, but acknowledged that in the immediate future, only incremental measures were feasible.

“In its 1992 Casey decision, the Supreme Court agreed that the State of Pennsylvania could regulate the abortion industry in a number of ways,” the document says. “These regulations do not afford any direct legal protection to the unborn child. Yet experience has shown that such regulations — genuine informed consent, waiting periods, parental notification — reduce abortions in a locality, especially when coupled with positive efforts to promote alternatives to abortion and service to women in crisis. A national effort to enact Pennsylvania-type regulations in all fifty states would be a modest but important step toward the America we seek.

“Congress also has the opportunity to contribute to legal reform of the abortion license,” the statement continued. “A number of proposals are now being debated in the Congress, including bans on certain methods of abortion and restrictions on federal funding of abortions. We believe that Congress should adopt these measures and that the President should sign them into law. Any criminal sanctions considered in such legislation should fall upon abortionists, not upon women in crisis. We further urge the discussion of means by which Congress could recognize the unborn child as a human person entitled to the protection of the Constitution.”

All of this is being fulfilled. “I don’t think Bush will be shy about signing pro-life legislation,” says the Christian Coalition’s Backlin. “He’s proved his courage in so many areas, and that will continue in the pro-life legislation field.”

Pro-choice activists can only hope that those who seek a different America begin to notice, and to care.