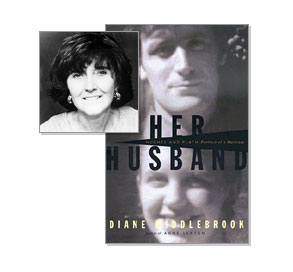

Diane Middlebrook has never shied away from controversy. Her biography of the poet Anne Sexton was a critical success — nominated for the National Book Award in 1991 — but it was also a national sensation, drawing from transcripts of Sexton’s sessions with one of her psychiatrists (with the family’s and psychiatrist’s consent) and revealing her affair with another. Her second biography, “Suits Me: The Double Life of Billy Tipton,” explored the life of a female jazz musician, born in 1914, who lived as a man from the age of 19 until she died in 1989, having fooled Duke Ellington and five wives and having “fathered” three children. But controversy is decidedly not the point, or even of particular interest to a writer like Middlebrook. Instead, the heart of the mystery seems always to be: How do artists become?

In this respect her latest biography, “Her Husband: Hughes and Plath, Portrait of a Marriage,” is no exception. It is not a biography of either Ted Hughes or Sylvia Plath, but a biography of their marriage, and it is safe to say that Middlebrook took this approach because within this first, youthful marriage, two of the 20th century’s most important poets came into being. For a time they prospered together. Like many married couples they also struggled: with romance and ambition, sex and work, children and mothers-in-law.

I first met Diane Middlebrook at a book salon in London, where she lives for part of the year with her husband, the chemist and playwright Carl Djerassi. (The couple spend the rest of their time in San Francisco, where Middlebrook is a professor emerita at Stanford University.) I told her I was writing a memoir about my experience getting married; she told me she had just completed a book about marriage herself. At first glance it seemed that our projects were very different, but Middlebrook knew immediately that we would have a lot to talk about, and she was right. Recently, we talked about “Her Husband.”

Most people know what went wrong in the marriage of Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. He fell in love with another woman, leaving Sylvia with their two very young children; she fell into a deep depression and took her own life. It ended notoriously badly. But in the book you argue that it was an extraordinarily productive marriage for both of them, even a lucky one.

Well, the marriage was about two things: One of them failed and the other succeeded. What failed was the formation of a new family. It failed because Sylvia Plath was not psychologically prepared — and by that I mean something quite respectful and descriptive — to absorb and accommodate a dimension of the man she was married to, which was just as characterological in him as her refusal of it was in her.

His need to …

His need to have sex partners outside the marriage for the continual restimulation of his creative powers.

Huh. But you could also say that it was Hughes’ fault for entering into a contract that according to most people requires fidelity.

You move immediately to the question of whose fault it was.

Right.

And I’m trying to be descriptive. My book is trying to say that you can understand these people if you set aside the question of who are you going to blame, and look at what happened. Because if this is a book about marriage, then it’s a case study of a failure, at one level, that is pretty interesting and common, in which the female in the pair is absolutely antagonized and threatened in her emotional security by the behavior of the male in the pair — and vice versa. Sylvia Plath’s sexual jealousy was a burden to Ted Hughes. It finally became an intolerable burden to him. His behavior cannot be admired, but it was, I argue, a lifesaving act on his part. But that’s quite aside from what they contracted for. They contracted to become a family.

But in her mind they’d also contracted to be faithful to each other sexually.

Well … can you contract for that?

A lot of people when they enter marriage believe that they are doing just that.

OK, let’s go to that question. Because I think the relationship that people form inside the contract of marriage is dynamic, and they mature and go on maturing inside of it through their psychological interaction. The notion that the contract can cover with rules the behavior of the people in it is, I think, highly questionable. I don’t believe you can ever, ever, ever predict how human beings will develop — there are too many factors at play.

But it’s a fundamental idea that a lot of people have about marriage, that it’s possible to promise yourself and your behavior for the rest of your life. That you are standing up there saying: By entering into this contract and this particular relationship, I promise for the rest of my life to behave a certain way, and faithfulness is part of that. The vows explicitly cover the sex question.

I don’t believe so. You can say, “I will be faithful to my pledge to understand you in your needs, which are different from mine.” But people don’t know what’s going to be expected of them. For example, if you have a rigid code that absolutely spells out not only what you may and may not do but what the punishment will be — and that’s a definition of “contract,” in my view — I don’t know of a single one that actually says to men: You can’t have sex with other women. Honestly I don’t. It’s females who are forbidden to practice adultery. It’s not men.

So in that context you could say that Ted Hughes, in his marriage to Sylvia Plath, did not breach the contract between them.

Yes, well. I don’t know what the contract was, you see.

It’s specific to each couple?

All I know for sure is that relationships are dynamic, and people don’t know what’s going to happen. They don’t know what’s going to happen in life, and they don’t know what’s going to happen inside their relationship, either. What he discovered, I believe, was that he had some needs that he didn’t understand at the time he married Plath, or that he didn’t think were important.

It’s not like it was premeditated … murder.

No! No. Well, as far as I know Hughes was not unfaithful to Sylvia Plath; he did not have sex with other women, during the first six years of their marriage. Their partnership was focused on their writing.

Well, let’s talk some more about that. We talked about how the marriage was in one sense a failure — in what sense was it a success?

Was it a success! It was the success that made them people you and I know the names of. Unlike most married people. Why? Because they became poets together. At the time that they met — I love this part of the story — neither one of them had brilliant prospects for success as artists. They were pretty good, but they were college students, and they were good at the college-student level: full of promise without much testing in the real world. But when they met each recognized the other’s talent and formed exorbitant expectations about where that talent might lead. When Sylvia Plath met him, the first thing she did was quote to him what he had written and published in a literary journal, that she had memorized. It was a magical moment for him and for her, too. It was the basis of their bond. Hughes calls it luck. In a letter to his brother, he says: Sylvia is my luck entirely.

That’s beautiful.

He was mad about her! And one of the things he loved was that she had exactly the kind of literary education that could appreciate everything he did, everything without exception. She had not only a kind of daffy goofy appreciation of him, such as one has for objects of desire when one is desiring them, but she also had the same education he did, and very good literary judgment.

And you point out in the book that they were exceptionally good critics for each other, while being incredibly supportive.

Yes. They provided the lab conditions for each other in their purposeful pursuit of a ridiculous professional decision. You know? I mean ridiculous! You don’t become a poet with any expectation of success in the material world. So how are you going to become a poet at all? How poets become poets always has a story of this kind somewhere in it. Somebody whose judgment matters to you keeps you going while you get to be good at it, which usually takes a hell of a long time even if you’re very talented.

Plath was incredibly ambitious. But one of the very interesting things I found out about in the book was her conventionality, too, her very 1950s husband-hunting while she was at Cambridge.

Well, they were both conventional in the assumption that they should marry.

Although she proposed to him.

She proposed to him, but he said, why not? I think. Remember, he came out of a family where people married or they weren’t respectable, or there was something wrong with them. Plath held the same view, as we know from her journals and from her poems. She thought that to be married was the only socially acceptable mature position for a woman. But he made a kind of unconventional marriage, and she did too.

They were a dual-career couple in the 1950s.

Yes. She figured out how it was going to work for her, and he figured out how it was going to work for him right away, because Sylvia Plath was not only a wonderful critic, she was a wonderful typist! So there was this ordinary side to their marriage, and then there was the extraordinary side, which was their discovery of each other as perfect counterparts in their developing vocations, the partner that luck had handed them. He said as much in “Birthday Letters,” where he makes the astrological claim that the solar system married them the night they met.

Obviously this is an exhaustively written-about and thought-about couple. Paul Alexander’s play “Edge” was performed in New York recently. He takes a very different view of their relationship. He presents it in a way that paints Hughes as the villain.

But Alexander is writing a play, which is a different genre entirely; it requires a dramatic arc. A biography is something else.

He’s written a biography as well [“Rough Magic: A Biography of Sylvia Plath”].

Well, to be charitable about the question, he didn’t have the advantage of the Ted Hughes archive. I believe that that archive absolutely once and for all changes the base for making a judgment about him. Lots of things can be found out about Ted Hughes in 2003 that couldn’t be known before.

So is it your belief that this entrenched view that has been so reinforced about Sylvia Plath as a victim of a husband who left her — and a father who died and left her, I’m thinking of her poem “Daddy” and of Alexander’s play — is it your belief that with the Ted Hughes archive being opened that that view will change?

Who knows? Society, culture absorbs information in the form of stories. And in the 20th century, we had a favorite story, the victim story, which was widely distributed in our culture. “Sylvia Plath was a victim of a bad man.”

She was made into a sort of victim poster girl.

I never thought that fit her very well, personally, but it was easily absorbed. Then too whenever people get a divorce, other people choose sides against one of the pair. Somebody is always to blame.

And when one member of the couple takes her life …

Well, yes, and then Sylvia Plath kills herself, and people think she killed herself because he left her. How do they know that? Sylvia Plath had already tried to kill herself. The available evidence suggests that she was having a repetition of the major clinical depression that she had had when she was 18. Her obsessional suicidal thoughts were symptoms of her illness. Suicide was a solution to the problem.

Which she wrote about in “The Bell Jar.”

“The Bell Jar” had just been published when she killed herself. I envision it as sitting in plain sight during the hours when she was deciding what to do. She had a suicide in her. And the options that Sylvia Plath might have seen would have been A) hospitalization, which she had been through before, and B) that her children might be taken away from her. I have never seen a shred of writing about this, but I feel pretty sure that that would have crossed her mind. Mental illness was held to be a very, very bad thing, and you definitely wouldn’t want children being raised by “a nut case.” As a British woman said to me, “Cut to the chase! Was Sylvia Plath a nutter or not?”

A nutter. That’s nice.

It was an important question to hear put so bluntly. Honestly, I can hardly bear to think about those last hours of Sylvia Plath’s life. I have a real rescue fantasy about this. If somebody had just put her in a place where she was safe, until she got better, and could come back to her children, I think she could have survived the breakup of her marriage.

And that marriage would have been a good thing for her. Just because a marriage ends doesn’t mean it’s a failure.

Yes, that’s what I think. Though I used to say to my female students, men can marry, but women shouldn’t.

Really. Were you married at the time?

No. I had observed in myself that I could have a relationship to a man that was pretty satisfactory, consoling, and even conflict-oriented, and that was fine as long as I wasn’t married to him. But as soon as I got married to him, all of a sudden I had a script playing in my head all the time. And feminism was saying: Let’s just take a look at this stuff. The personal is political, so where’s the politics? Well, the politics was the politics of being the wife, in my head. When I married my current husband, my last husband, I had outgrown the script. I wasn’t going to have children with him, and we both were well-established in our professional worlds.

You were beyond the script.

Literally beyond it. So we can make it up as we go along. I can’t tell you how gratifying it is to make it up as you go along. It’s wonderful! Because at any given moment you can say, I think we’re doing this all wrong. I’m not happy with this. Or, what would happen if we did this? The conventions don’t rule you the way they do when you’re a reproductive pair. Because there’s no question that women bear a different kind of emotional responsibility for child raising from men.

And still you think this is true? I’m certain it’s true right now.

I just realized who I was talking to.

The three-months’ pregnant writer. I think about this all the time. About how my husband and I will handle it, and what will happen to my work. One of things I was feeling, being a newly pregnant woman writer reading your book, was Sylvia Plath’s worry and anxiety over whether she had to make a choice between her writing, her career, and being a wife and mother. And even now, in this post-feminist universe, I worry over it too.

The way she formulates her options in her journal is that marriage will probably require that her writing become secondary, so there’s the conflict. She gives caps to writing and to life. For life, she needs to be married —

And to be a mother.

And to bear children. Let’s preserve that distinction if we may, because childbearing is what she thinks about; she doesn’t think about children. She’s thinking about accessing her fertility, if you want to put it that way. That’s not her phrase for it, but the consistent references in Plath have to do with a celebration of her fertility.

And with confirming it. She needs to know she’s fertile.

And confirming it! But the outcome of being fertile is really not in her imagination. She’s not drawn to children, she doesn’t fantasize about them, their little shining faces.

She does seem, for awhile, to have it all.

Yes. And Plath truly enjoyed caring for her children.

She’s so different from Anne Sexton in that regard.

And boy, I’m on Sexton’s side in a lot of ways on this one. Let somebody else take care of the children! Women aren’t good at taking care of children just because they’re female. That is very important to know in life. It doesn’t come with the territory of being female, at all. Plath understood this. Her poetry contains recognition of the biological bond, which is endocrinological, between herself and the baby while she breast-feeds. But what’s voluntary, what has to be created inside her because it doesn’t come with the breast milk, is love. Is fascination, is benign, benevolent curiosity.

It must have been fascinating, having written a biography of Sexton, who is so often connected with Plath. I was struck by how different these two women are, and how different their marriages were, if you want to look at that part of their lives.

Yes. Sexton had a wife, so to speak. (Her husband, Kayo Sexton.) Actually she had something better. She had the extended family in which the other people were caretakers. And thank god! Because women have to be able to hand off child care, if they’re going to be able to do other things. If you’re going to be creative you have to be able to hand it off. In Plath’s case, she had a man who acknowledged, without apparent difficulty: We’ve got this child to take care of, so you get the morning and I get the afternoon.

They shared child-care 50-50!

Which he does mention to Aurelia Plath — somewhat annoyed, like he doesn’t get proper credit for this — that Plath regarded her writing time as the most important writing time in the house. That was the most important writing time in the house! Now if we want to talk about selfish, my dear.

OK. Let’s talk about sex. There’s a lot of sexuality and sensuality in your book in talking about their marriage, and especially their courtship.

Which she wrote about so often. So vividly.

Especially in that amazing, famous journal entry you spend a lot of time on. Clearly they turn each other on from the beginning, if bleeding is any sign. How important was sex to their relationship?

Well, it was an instant test that they gave each other.

The poetry first —

Yes, poetry first, then sex. They established the priorities right away. I don’t know much time elapsed from the time that she said, “I did it, I,” till she bit his cheek and he grabbed her earrings and walked out of the door. But it wasn’t very much time. Right away they knew that they were attuned to each other. They didn’t follow up right away. It took a little while for things to clarify.

But that first encounter and the way they physically interacted with each other that first time was pretty telling …

It was a paradigm, I think. At least it was the paradigm that Plath chose to write about. And we have to be aware that many of the things we think we know about Sylvia Plath come from her journals, and she’s always heightening things.

The journals are one of the things Paul Alexander uses — just to bring him up again — to put forth his understanding of their story, in which Ted Hughes is somewhat abusive. They had rough sex.

Well, Kamy, may I just politely observe that “abusive” is another loaded cultural term? It’s a huge umbrella! And it doesn’t fit very well over sexual transactions, it seems to me. Because aggression is very important in people’s sexuality, one way or another. In the spectrum of possible aggression-expression in sex, they seemed to have been on the heavy-duty end. But there is no sexual encounter that does not have some aggression in it. None! According to Freud, according to experience! And their sexuality seemed to have been most gratifying when it licensed some expression of the primitive. This is where D.H. Lawrence is very important.

We should talk about that. Lawrence was very important to both of them.

Like Lawrence, Hughes held the view that the authentic experience of sex is an expression of animal force, vitality — animal vitality, that is. And in his lexicon there’s a metaphorical violence to it. But sex is not experienced in words. It’s experienced in physical sensation and the urge to do it! What flows from that intensity is language, of course, because we need to capture it. But I don’t think the terms “abusive” and “violent” and even “masochistic” and “sadistic,” “S/M,” I don’t think they can justifiably be applied to the register of their sexuality. It definitely was an expression of great importance — given the frequency — to both of them.

I love the New Year’s resolution to have Friday afternoon blowups, followed by makeup sex.

That’s right! Friday afternoon blowups, because the sex is better when you’ve had a blowup to stimulate you!

And they seem to be in sync.

Very much. And the pleasure principle seems to be the point there. I personally think that people who are trying to put together a brief against Ted Hughes can go to those things and say “violent and abusive,” missing the point entirely. Their sexuality was a core expression of their bond, and it had a lot of intensity and negative charge in it.

And mutuality. That’s probably the most important thing.

It is the most important thing.

I was struck by Plath being, for 1956, or the mid-1950s, a very sexual person.

Me too!

And that she was sexually active, before marriage.

I was interested in tracking her discovery of her sexuality. And we can track it because of letters in her archive addressed to Eddie Cohen, a man she began corresponding with just before she went to college. Plath published a story in Seventeen magazine, and he wrote her a fan letter that initiated an active correspondence. After she confided to him her feelings about the injustice of the double standard, he more or less became her consultant on sex, giving her a man’s point of view.

She was very angry about that idea that —

Men could have sex and women couldn’t.

Right. Before marriage.

Right, for fear of pregnancy.

You get the feeling she’d be happy about your husband’s invention of the pill.

She was happy enough when she got a diaphragm! But Cohen encouraged her to practice, practice, practice. He encouraged her to masturbate, and to experience orgasm. He said you had to learn how to do it.

That’s very forward-thinking.

I’ll say. And she did learn. I paraphrased the juiciest things I could find in her journal, about the way she achieved satisfaction by rubbing against her partner — rubbing together their “tender pointed slopes.”

Ooh, a very poetic description of a dry hump.

Right, a dry hump, as we would say. See? What a put-down, eh? But she gives it poetic language because she really loved it, it was delicious. And it was what she felt safe doing.

I have to say, I mean, on Hughes’ side of things, he did seem to have a distinctive sexual style. It wasn’t just in his relationship with her. When he went on after she was gone with other women, he seemed to think of himself as a hunter. Is that true?

Well, that’s my account of him. I don’t believe he applies that to himself and his sexuality, although his account, in a consistent, ongoing way, of men’s sexuality is that they’re driven by what he calls the zest of the sperm. There’s this principle of vitality in you that’s always looking for an expression of itself. And it has no interest in any social contract.

That’s the heart of the matter.

It’s biological. But Hughes knows that the zest of the sperm is also embedded in the religious tradition in the story of creation. God created Adam, and two women. There’s Eve, and for her there’s only one man. But there’s Adam, and for him, there’s Lilith!

His wife and his mistress, from the beginning.

From the beginning. And Hughes doesn’t spell it out, by the way. I’m attributing to him an interpretation I made of his use of Lilith in the poem I’m thinking of, which was written to Assia, the “other woman” in his life with Plath.

I guess this brings us to one of the other things we’ve talked about before, which is the adultery dispensation for the rich, talented and famous. Mostly for men, but women, too — Sexton, notably. If you look at the biographies of major artistic figures, or just of ambitious, extraordinary people, there’s a lot of adultery there.

Yes, there’s a lot of adultery in their biographies. And there’s a lot of adultery in the literary world of London. It wasn’t just adultery. There is a different social, sexual milieu of Englishness that makes Americans look puritanical. Now Ted Hughes was raised in a puritanical environment himself. But in the world of literary London, where people just freely exchanged partners and there was just a lot of casual sex, adultery was an expression of being a bohemian, so to speak.

In that sense he was almost behaving in a more conventional way than she was.

In a very conventional way! And that’s why, his friends said at the time, and even put in their memoirs now, that she really made far too much of it. What she needed was some good advice from a maternal figure, you know: Let him get it out of his system. And that would have been the way a family-oriented advisor would have spoken to her.

Or a literary-bohemian-oriented advisor. There’s some notion that a monogamous, rule-bound marriage is not functional for artists.

It’s not functional for anybody, in my view.

That’s controversial.

You know what the rules are, and then you see that — it depends on what “is” is. If only it were clearer what you should do in any given situation. If only it were! If only it were, how happy we would — or no, how dull it would be. This is why people are interested in reading about other people’s marriages. What do they actually do when push comes to shove, and people make — I almost said “make mistakes,” but I won’t say that. Let me put it this way. When one person hurts another person, but actually loves them, too, how do both of them deal with it? Because the rules just don’t cover all the cases.

I know in the book that you’re really trying to look most closely at Ted Hughes’ creative development and his creative crisis. But we do get to see that he marries again, and within that marriage he does find a woman who seems to be at least tolerant of his need to continue pursuing affairs —

Hughes doesn’t have another marriage until 1970. Instead he finds a variety of rather unsatisfactory circumstances under which to take care of the children. Aurelia Plath wants to take care of them on her daughter’s behalf, and Hughes refuses this. He hires nannies, he gets help from his sister, he involves Assia [the woman Hughes had the affair with while he was married to Plath], who has a baby, and as I say, he creates a tribe in which he’s the chief. So the solutions are really kind of fluid until 1970 when he marries a woman who really has the ability and the desire, apparently, or the will, to take care of the children with him. He hasn’t solved the problem of his creativity, though. That’s what I’m talking about in my book. How is Ted Hughes going to solve the problem of being a poet on the scale he aspires to? A poet on the scale of Yeats, on the scale of T.S. Eliot. How did he get there? That’s my question. Because he indubitably did. And I don’t know what role his last marriage played in his achievement, but I do know what role his relationships outside his marriage played in it.

And you do know what role his marriage to Plath played in it.

Yes, I do know what role his marriage to Plath played in it. He referred to the marriage to Plath as a marriage that was his contact with what he would have called the feminine principle, the “goddess of complete being.” Which doesn’t mean she was complete in herself, but that his being is completed in conjunction with her.

So even after Plath’s death, it remains important to talk about the two marriages, which you introduced at the very beginning of our conversation. Because while the reproductive unit marriage failed, and truly ended with her death, the other marriage continues.

It continues to the end of his life. And there is a poem which is the last poem in the marriage, which I designate: “The Offers.” In this poem Plath returns to Hughes in a dream, younger than she’s ever been, flawless, and she says to him, “This time, don’t fail me.” That marriage goes on, and he doesn’t fail it.

Hence, “Her Husband.”

Yes.

So, I’m still hung up on this adultery thing.

That’s OK.

One of the things I’ve been writing about, that I write about in my book, parts of which you’ve read, was my struggle as I contemplated getting married with the idea of fidelity, and my fear of failing at it. I felt like I had to believe that I could stop pursuing sexual relationships with other men, for the rest of my life, or I couldn’t marry. I felt like I had to believe I could stop doing that.

OK, but can I interrupt you and say, presumably, that you were projecting into the future. But to be businesslike, how long is the future?

Till you die!

My dear! You have no idea how long you’re going to live. I think if you’re a serious person you understand that you are doing your best.

Yes.

And you don’t know what’s going to happen in your life, but you are going to try your best.

I promise to try my best. Well, back to Plath and Hughes.

But you see, I wrote this book because I think this is so fundamental: Marriage is a commitment to form coping mechanisms with which to handle the unintended consequences!

I sensed that reading the book. It’s a very literary book, but at the same time it’s really dealing with marriage, not just Hughes’ and Plath’s marriage, but ideas about marriage itself. Do you see it as a book for people struggling and prospering in their own marriages?

Yes, because I’ve had three of them!

And your ideas about marriage were basically the same as Sylvia Plath’s?

Pretty much. I was born in 1939 and she was born in 1932. But the world of Spokane, Wash., let’s say there was a bit of cultural lag there. But marriage was the destiny of a girl; and nice girls did not have sex outside of marriage. I had sex outside of marriage so I married the guy I had sex with. Then I got a fellowship and I left the man that I’d had sex with and gotten married to. The conflict between my writing and my life, so to speak — what a muddle. So I sympathized with Sylvia Plath’s struggle very much. But I won’t go on personalizing Sylvia Plath’s script. I’ll just say that as I got older myself I got more interested in the fact that men and women have different stakes in marriage.

What was it like writing about two people who have been so written about?

I limited myself to writing about their marriage, partly because it turns out to be such an important theme in the work of both of them. The availability of Hughes’ papers after his death made it possible to probe this subject without inhibitions.

It is really a biography of a marriage.

Theirs was one of the most important literary marriages ever. And one of the reasons is that as her survivor, and as her executor, Hughes made Plath famous. He did! And then he wrote himself into the story of their marriage, and made them inseparable.

Would you ever do a biography of someone who was still living?

Never. No.

You didn’t start this project until after Hughes’ death.

Not just after he died, but also with the knowledge that Hughes himself had selected everything in the archive he sold to Emory University in Atlanta. I thought, well, Ted Hughes has a reputation in the world of a man who doesn’t want to be known … I don’t think so! I really understood, too, how Ted Hughes got the reputation of being a man who didn’t want to be known. He was protecting is privacy, but in addition, he wanted to write about his life. And he did. He didn’t want journalists writing about his life. You make talk and journalists turn it into writing. And as Janet Malcolm says in “The Journalist and the Murderer,” it’s the journalist’s story, not yours.

And it’s the biographer’s story.

Yes.

What’s next for you?

My next project is a biography of somebody who’s been dead for 2,000 years, the Roman poet Ovid.

You couldn’t be much deader than that!

No estate, nobody to interview, and actually, no history. Just me and him!

– – – – – – – – – – – –

We want to make you a part of this series. What is the state of your union? Did you find the one and never look back, or has finding lasting love been a marathon of trial and error? Did you have a fairy-tale wedding only to watch things crumble once the reception was over, or have you glided along in marital bliss since Day One? We want to hear your stories of joy, romance, heartbreak and pain. After all, partnership, as we all know, is a complex concoction of all of those things. (Please remember: Any writing submitted becomes the property of Salon if we publish it. We reserve the right to edit submissions, and cannot reply to every writer. Interested contributors should send their stories to marriage@salon.com.)