While teen pregnancy rates fell during the 1990s, the national rate is still miles above other industrialized countries. Four out of 10 teens will become pregnant before they are 20. In the South, where 55 percent of schools receive federal funding that prohibits them from endorsing contraception, birthrates are significantly higher than average.

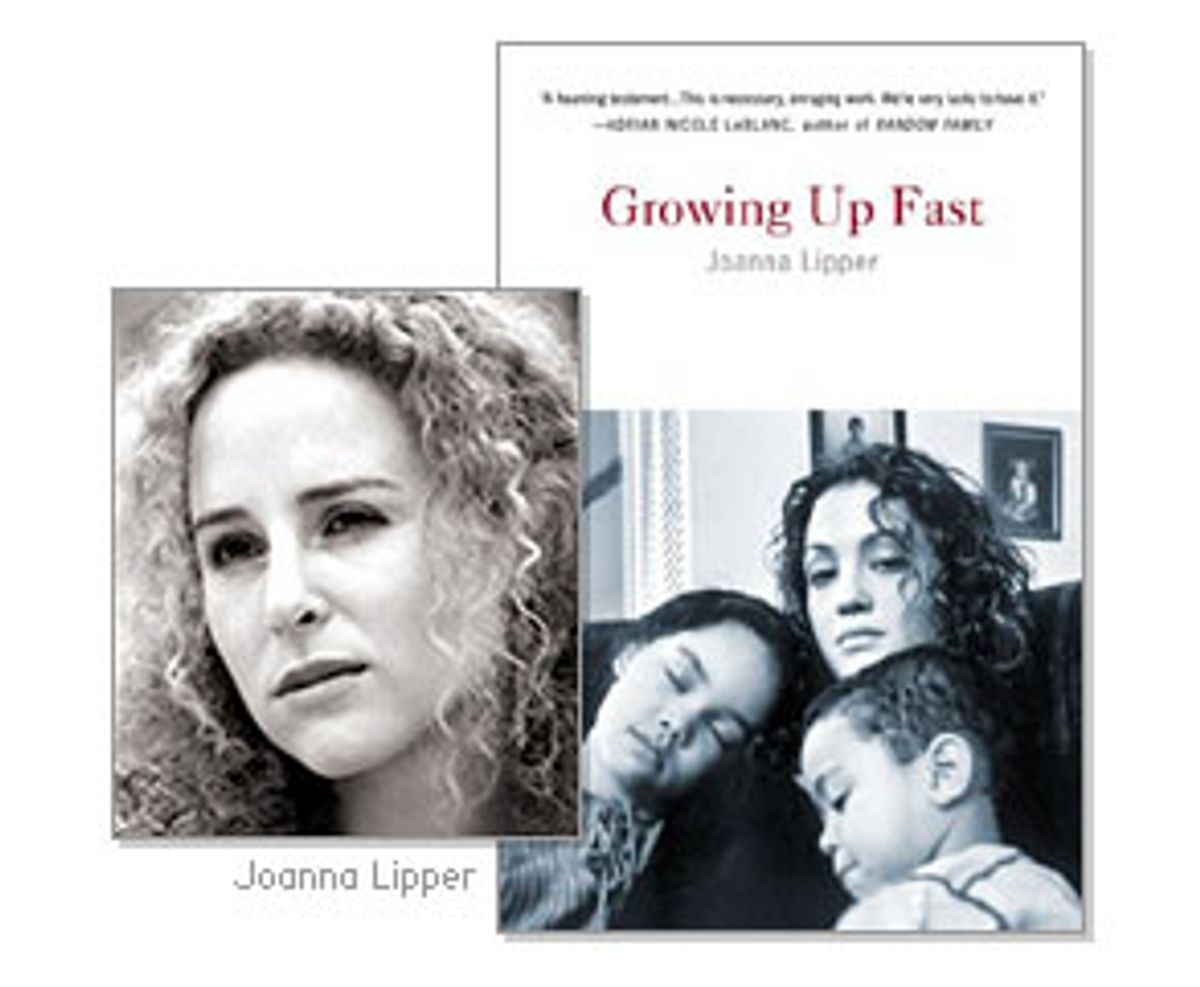

In her new book, "Growing Up Fast," filmmaker Joanna Lipper follows six teenage mothers from the working class town of Pittsfield, Mass. -- Amy, Liz, Colleen, Shayla, Sheri, and Jessica -- over a period of four years as they navigate a rocky adolescence, with a baby (or two) on their hip and a whole lot of baggage. "Growing Up Fast" began as a documentary film by the same name. Asked by psychologist Carol Gilligan to videotape writing workshops she was conducting at a teen parent program in Pittsfield, Lipper was so inspired by the stories she heard that after the six-week program ended, she decided to stick around and get to know the girls -- their problems, their hopes, and their children -- on a deeper level.

Pittsfield, once the main manufacturing base for General Electric, has become an economic and cultural ghost town ever since the company left in 1986. "Growing Up Fast" explores the girls' circumscribed worlds -- fast food chains, dank daycare centers and violent housing projects -- and uncovers six histories marked by abuse, poverty and low expectations. Although each girl "longed to be independent and self-sufficient," Lipper writes, "they confessed that they had never taken the SAT, nor did they remember ever being told that the test was required for admission to most four-year colleges." (Not surprising, according to the Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention program,only about one out of every three teen mothers finishes high school.) Far from isolated cases, Lipper argues that these women are part of a complex social web, and her book is a touching treatise on the role of individuality, responsibility and luck in American society.

Salon recently spoke with Lipper about teen sexuality, family values, and six young mothers who are doing everything they can to beat the odds.

This project began as a 30-minute documentary. What motivated you to spend an additional four years of your life writing a book in what Jessica, one of the teen mothers profiled, called a town so boring that there's nothing else to do but have sex?

It began when Carol Gilligan asked me to videotape writing workshops she and Normi Noel were conducting at the teen parent program in Pittsfield -- and when Carol Gilligan calls, you come! But what made me stay after the documentary were the oral histories I encountered. I let the words of my subjects dictate my research. It was my talks with Bill, Jessica's stepfather, that led me to research the devastating effect GE's departure had on the town. Liz's experiences drove me to study foster care, sexual abuse, and the juvenile justice system. These are the stories that inspired me. And while they are incredibly detailed and specific in their own right, they are not isolated cases. They reveal a lot about American society as a whole.

Given that trust does not come easily to these girls, their candor is remarkable. How did you gain access into their lives, win their confidence and that of their family members?

It was definitely a gradual process. The fact that all the girls were already in a teen parent program was very helpful. And with Carol and Normi's workshop, they were starting to become more confident in sharing their feelings. As time went on, I met with them more individually. One day I'd go with Amy to pick up Kaleigh, her daughter, from daycare. Or I'd stop by Friendly's, a fast-food restaurant, early when she was on the morning shift. I did whatever I could to fit into their lives on their terms.

And while it's difficult to generalize because each girl had her own individual motivations, it is fair to say that they were eager to defend themselves against the normal stereotypes and stigmas about teen parents. In speaking to me, they seemed to say, "Rather than accept someone else's definition of me, I would like the chance to define myself." And that journey of speaking for yourself and defining who you are is in many ways a rebellious act against a society that wants to label, marginalize, and ultimately write you off. That's why I end the book with Sheri saying, "When I was pregnant lots of people told me, 'You're gonna be a teen mom -- you're life is over.' Whoever says that to teen mothers is lying. My life is just beginning."

Speaking of marginalization, 83 percent of teen births are to poor moms. Only 17 percent are to higher income teens, since nearly three-quarters of them have abortions. What do you think accounts for the connection between poverty and teen pregnancy?

On a practical level, these kids are not getting the same opportunities at school as their wealthier counterparts, because instead of using free time to do homework and extra curricular activities, they're working. Jessica had so many jobs before she became pregnant -- at Burger King, Pretzel Time, Bonanza, you name it -- all before she was 16. When you aren't economically burdened, there is the expectation that you're going to graduate and go onto college, where you'll meet new people and new doors will open. For many economically disadvantaged girls, however, there simply isn't such an established "rite of passage." Or, too often, if there is one, it means going from working part-time at Burger King to working full-time, from cleaning rooms at a hotel during high school to cleaning rooms afterwards at a bed and breakfast.

So did these girls become parents because they saw no reason to avoid it?

While most teen pregnancies are unintentional, many do "fall into it" because they lack any other appealing options. But that's not to say they have no desire to participate in their world, or that they utterly lack motivation. The sociologist Kristin Luker has noted that for many low-income girls love is one of the most valuable resources they have to give. Having kids allows them to define a place in society for themselves. They become more involved, more connected -- their kids go to school, they use services. The children also become vessels for their hopes and dreams. Interestingly, many of the girls altered the spelling of their children's names -- Ezekiel became Ezakeil; Leah became Leeah. It seemed to be their way of saying their children are special, unique, and would hopefully have a better childhood than they had had.

Let's talk about the girls' environments growing up, because their untimely pregnancies were always presented as one of many problems -- a parent's addiction, poverty, poor foster care, and especially domestic violence and sexual abuse. And violence only seems to beget more violence. One of the girls, Colleen, was beaten badly by the baby's father during her pregnancy and her son, Jonathan, was born with cerebral palsy -- which has many possible causes including severe physical trauma which can cause a stroke in utero.

In my endnotes I cite studies which have found that almost 60 percent of pregnant teens report histories of sexual abuse. Twenty percent of high school girls say they've been physically or sexually abused by a dating partner. We spend millions on teaching young kids to avoid the dangers of smoking and alcohol, and yet sexual abuse, which is equally devastating, is so often hidden. This may be slowly changing, with movies like "Mystic River" and the coverage of the crisis surrounding sexual abuse in the Catholic Church, but it's interesting that it's so often about priests and young boys. There was "The Pledge," a great movie directed by Sean Penn starring Jack Nicholson, and it was about the sexual abuse and murder of a young girl, but it didn't get nearly as much attention.

Silence and denial are major themes in the book -- particularly as they relate to teen sexuality. These girls grew up at a time when Britney Spears (and countless others) ignited social anxieties about girls' sexuality -- stripping one minute, pledging to remain a virgin until marriage the next. In fact, a few weeks ago the governor of Maryland's wife said she wanted to shoot Britney, not long after she french-kissed Madonna.

One of the things that characterizes countries with a low teen pregnancy rate is their acceptance of teen sexuality. So the fact that it's such a conflicted topic in the U.S. leads to silence. If someone can't talk about something and discuss it, they are more likely to enact it. You see the effects of this silence in the girls who hide their pregnancies for six months. Or in Jessica, who got pregnant after lacking the energy to refuse her boyfriend's advances. She was tired, had no ride home, and worried that objecting would cause a fight.

So remaining silent about teen sexuality has consequences. Most girls don't even know what consent is -- literally, how and how not to give it -- so when you're talking about comprehensive sex education you can't only focus on sex, but rather you need to focus on gender identity, on how to have a relationship with someone, and on how to express yourself. In my book there are examples of programs, like the Council Program with its Mysteries Curriculum, that do just that.

Yet in recent years, politicians have spent approximately $300 million supporting abstinence-only programs. Consequently, over one-third of U.S. school districts have policies that require educators to teach students that abstinence is the only effective way to prevent pregnancy and STDs. In fact, they are not even allowed to discuss contraception, except to discount its effectiveness.

The abstinence-only movement perpetuates the problem of teen pregnancy, since it's largely based on silence about sexuality and a refusal to discuss it in an educational framework. This is not the case in countries like Sweden or France, where people acknowledge that teenagers are sexual creatures, and don't punish them or make them feel that they are doing something bad, but rather try to help them. Consequently, according to a study done by the Alan Guttmacher Institute, teen birthrates here are approximately four times higher than in Sweden and France. I mean, how can you teach someone about, say, consent and alcohol in an abstinence-only program if you can't talk about sex? How can you talk about what happens when you're drunk and you might not have the inhibitions, judgment, or decision making skills you normally would?

In his book "The Broken Hearth: Reversing the Moral Collapse of the American Family," William Bennett argues that social services, like welfare, only encourage out-of-wedlock births. As a remedy, he suggests cutting benefits to this population, starting with unmarried teenage mothers. Why do teen moms provoke so much vilification and resentment in our society?

For one thing, pregnancy can't be hidden. Sexual abuse can be hidden. Domestic violence can be hidden. But not pregnancy. It's undeniable. So with these girls, their bodies spoke for them. Their bodies said what society does not want to verbalize. And this has incredible implications, economically and socially, that most people would rather not confront. When you hear Liz talking about being in foster care or being absent from school for several semesters and no one caring, you start to see a mirror of society in her experiences. One of best lines about how society regards teenage mothers is in Toni Morrison's book "The Bluest Eye," where the narrator talks about Pecola, a young girl who became pregnant after being raped by her father: "We tried to see her without looking at her, and never, never went near. Not because she was absurd, or repulsive, or because we were frightened, but because we had failed her ... We were so beautiful when we stood astride her ugliness ... We honed our egos on her, padded our characters with her frailty, and yawned in the fantasy of our strength." Of course, when you meet these girls in the flesh you see that they are hardly destructive forces, but beautiful, young, hardworking women.

In the past few years, there have been a number of books, such as "Queen Bees and Wannabes," that suggest teen girls are hardly passive creatures, but rather brutal social opportunists. The recent movie "Thirteen" also plays on this theme. How do you see your book in relationship to these works?

This is a totally different kind of book. The authors that inspired me were Dorothy Allison, Rick Bragg, Studs Terkel and Barbara Ehrenreich. The book is about teenage girls, but it's primarily about American society. Through these girls, I wanted to write about the experience of being in an American family that is struggling. There are a lot of characters in the book, including male characters -- a police officer, a worker at GE, educators, teen fathers, a Vietnam vet and a doctor. I never wanted to look at these teenage mothers in isolation. It's really about the interplay between them and society.

As for risks, stories are presented and readers have a right to judge the girls. Readers can and will bring their own perspectives to it; and I hope they learn something about themselves from the book. I hope the amount of information I provide precludes any threat of exploitation, however. No one incident, no one mistake, is ever presented without context. In the time I was in Pittsfield, good and bad decisions were made. That's life.

Toward the end of the book Jessica, who attends community college, works part-time, and has sole responsibility for her child, says, "I don't want to be on welfare. I'm trying to do what I have to do to get off of it. I don't want to be stuck in the system, but thank God for the system." How important are social safety nets? And how do our safety nets compare to those of other industrialized nations? In France, for instance, emergency contraception can be handed out in high schools.

The United States has the largest gap between rich and poor among industrialized countries, and yet many other nations offer more support to youth during the transition from adolescence to adulthood -- and the existing support to American youth is dwindling as many programs -- particularly those in education, health, and human services -- are being cut left and right in attempts to rein in state budgets. In some European countries, kids don't already have to be suffering or be a teen parent to get services and support in the transition from childhood to adulthood. But in America, the belief is that every individual is responsible for her or his own destiny and welfare, but that can be difficult especially when there is such disparity in, say, public education.

Welfare reform -- with its five-year limit, long work requirements, tough sanctions, and strict rule that teenage moms must live with a parent or a guardian -- has made it challenging for these girls. If this country properly funded many of the innovative prevention and education programs I write about in the last chapter of the book, there is a good chance that we might come closer to a more cost-effective and positive strategy -- for society at large and young mothers. I can't say it enough: Far from being lazy and unmotivated, as the right and others so often label them, these teen moms prove not only through their own lives, their jobs, and their kids, but through their own dedication to this book that they are motivated, and that they do want to make a difference. They want a place in the world.

Shares