On the first night of “Operation Iron Hammer,” the continual and thundering boom of the American bombing sent me and my housemates up onto our roof to try to figure out what the hell was going on. The bass repetition of the sound clearly distinguished the bombings from the occasional mortars launched by the Iraqi “resistance” that we’d heard at night in recent weeks. There was no doubt: These bombs were big, they were plentiful, and they were truly frightening. A group of us leaned against the roof’s low wall, peered into the dark and guessed vaguely at the intended target. Around the neighborhood, silhouettes of Iraqis on their own roofs stood out against the night sky. One housemate — a guy who was in Baghdad throughout the war — likened the sounds to the “shock and awe” blanketing of the city during those days. After about 15 minutes, the noise ended and we went back inside to watch the news on television.

Since that first night, the Bush administration has been touting “Operation Iron Hammer” as its response to the stepped-up violence against American soldiers in Iraq. It’s a means of squashing the Baathist “dead-enders” (as the president has come to refer to them) with a strong show of American assault technology. The administration seems to revel in heavy-handed branding of military action, imbuing all operations with a tough-talking grandiosity. I often try to picture the room in which young members of the administration sit around and pitch potential labels for these operations. Or, no, perhaps it’s a single insomniac general with creative writing aspirations and a very big thesaurus. One thing is certain — there are no historians or fact-checkers working the job. If there were, they would have politely advised the president that “Iron Hammer” already has a claim to fame. In 1943 and again in 1945, Hitler developed Plan Iron Hammer to wipe out Soviet electrical capacity by attacking the country’s main turbine stations. In both cases, Iron Hammer failed completely.

On Wednesday, I went out with my driver and translator to see the results of the bombing around Baghdad. Though the operation continued to make enormous noise over the course of a few nights (in addition to the bombing, we can hear the stuttering sound made by the helicopter gunships as they strafe their targets) there was surprisingly little talk or information about what all that firepower had done. But then, I had been in bed for five days with the flu and hadn’t been out in the city at all. Still, even television and newspaper coverage that I woozily accessed was emphasizing the action in cities outside of Baghdad, with slight coverage of any destruction in Baghdad itself.

We drove to the Dora neighborhood, directly across the Tigris from the Jadriya neighborhood where I live. As we crossed a bridge linking the two neighborhoods, I saw a long line of cars snaking back from a gas station up ahead. Electrical towers have been falling down in the north — a result of high winds, outdated construction, and saboteurs. The diminished power impedes production at the oil refinery. Hence the long lines, and the long, long waits. Men sit in their cars or get out to chat in groups on the road’s shoulder. When the line moves, they help each other push their cars a few meters forward, leaving the engines off to save benzene (the word always used for gasoline here). I haven’t seen lines like that since the summer and it’s a depressing sight. Power shortages also mean that the main Baghdad grid has been down more than usual, leaving much of the city without electricity for half-day or daylong stretches. The house I live in has a dumpster-size generator that picks up most of the slack in those cases. But the majority of Iraqis in Baghdad can’t afford such a luxury.

We flagged an Iraqi police officer to ask about the bomb sites. He pointed us toward a dirt track next to the benzene station. The track wound past some makeshift brick and metal shacks and led to a huge dirt plain. In the distance, a couple of half-destroyed bunkers sagged ground-ward like shot elephants. It felt strange to find such a wide-open space in the middle of Baghdad. Usually, a space like that would at least contain trash heaps or improvised soccer fields. But when we stopped to speak to some men who lived in a few poor, ad hoc houses on the edge of the open area, they explained that it had been a military compound, occupied by Iraqis before the war and Americans right after. The Americans left it sometime in July and, though a few dwellings ringed the perimeter, it remained essentially barren.

The men showed me where, the night before, bombs had landed on and around the empty bunkers, leaving armchair-size holes, and scattering chunks of dry earth, bricks and rebar. For the past three days, the men said, American convoys had been showing up in the afternoons to tell the men to leave overnight and sleep near the benzene station. They would be bombing, the soldiers said. Military exercises. On the first two nights, nothing happened. So, on the third night, the families stayed in their homes rather than sleep in the open, in the cold. (Temperatures have dropped with dramatic suddenness over the last week. In the house at night we’re wearing sweaters and using heavy blankets. Even during the day, the air has a distinct chill and the sun, an unrelentingly fierce presence all summer, feels like little more than a stage prop.)

That third night — the night before I spoke to the men — the helicopters came.

Basam, a young guy wearing a black, knit, Nike-swooshed cap pulled down to his eyes, ancient jogging pants and broken plastic sandals, told me through my translator: “The bombing started at 9 o’clock. It shook the house so much, I couldn’t get my sandals on. I ran to a door that I knew was locked, but I was so scared, I kept pulling, pulling on the handle.” Eventually, he and his family got out and ran for the safety of the main road, where they stayed many hours after the bombing had stopped. Some of them, he said, were vomiting from fear. When I spoke to Basam and his neighbors, they were about to gather their things so they could go to the benzene station before sunset to spend the night. They anticipated the Americans would be coming again.

I stood and talked for a little while longer with the men, trying to make sense of how their descriptions of the previous night lined up with the bluster and resistance-busting intentions of “Operation Iron Hammer.” I asked them whether the abandoned bunkers and land had been used as a launching place for resistance-fired mortars. They assured me that it hadn’t. “We’re here all the time,” Basam said. “And we can see everything.” He swept his arm across the empty plain. Also, the men said, if the Americans wanted to catch resistance fighters, why did they come in convoys every afternoon to warn people of the impending operations? It’s just a show of force, they told me. It’s to make a big noise.

Standing in that very desolate place, I felt inclined to agree with Basam and the other men. It seemed possible that the strategy behind Operation Iron Hammer lay, at least in part, in demonstrating the breadth of American firepower without actually killing anyone. Intelligence about the resistance has been notoriously spotty. Every night soldiers raid homes, only to discover that the correct target lies down the street or a few blocks away. Or even that the tips themselves (encouraged by heavy reward money) came from disgruntled neighbors intent on solving personal disputes. If American bombing killed a neighborhood’s worth of innocent Iraqis right now, it could easily spark a massive and dangerous backlash. In other words, Iron Hammer seems intended to be (at least in Baghdad) heavy on the sound and light on the fury.

Lt. Col. Mark Coats, whom I met later that day at a checkpoint for trucks entering the Green Zone (the barricaded encampment where the American government has its headquarters here), didn’t agree with that theory. As he tells it, the AC130 gunships are directly targeting resistance all the time. “Those things are in the air, and when the bad guys fire something, they triangulate and find the spot and kill what’s there.” I drove to the checkpoint because I wanted to find out whether any of the bombs I had been hearing at night were Iraqi shells headed for the Green Zone. That particular checkpoint lies on a road along the Tigris, less than half a mile, as the crow flies (and across the river), from the house I live in. The road has been transformed into a special trucks-only entrance to the secured Green Zone area. Trucks edge forward over the deep speed-reducing divots that striate the road. At one spot, American subcontractor employees (who seem to be mostly giant-gutted, middle-aged white guys in baseball caps) check the drivers’ paperwork. A little farther down the road, trucks pass through an X-ray machine shaped like a giant houseless doorway.

Lt. Col. Coats told me that he thinks Iraq is a wonderful country. He’s become good friends with many Iraqis, he said, and he’s glad to see that things here are getting better all the time. Security is better. The infrastructure is rapidly being fixed. Iron Hammer has the bad guys on the run.

We stood on the roadside and watched the trucks. Nearby, three soldiers wrestled the metal stem of a large “No Photographs” sign into the dirt. Reeds and scrub nodded against the wind and the river looked almost blue to me. I commented that it was a nice spot to work. The lieutenant colonel agreed. “But we’re putting up the cement T-barriers between the road and the river tonight,” he said. Meaning a very high, very thick wall.

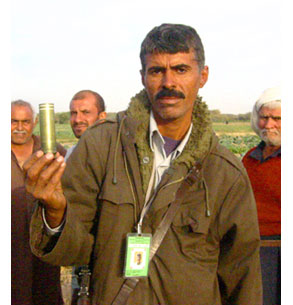

As we were driving away from the checkpoint, an Iraqi man with a Kalashnikov and a Facility Protection Service badge (which means he is officially employed by the U.S. as a guard) stopped us and spoke animatedly to my translator, Amjad. After a minute, he jumped in the car and directed us toward a nearby side road. “The Americans bombed his farm last night,” Amjad told me. “He’s taking us to see.” We drove past a dilapidated playground, then past some scattered trees where a few cows nosed around the grass. Very quickly, we came to a small farm. We couldn’t have been more than a quarter-mile from the checkpoint. The man, who introduced himself as Hamza, headed off with long and purposeful strides toward the middle of his furrowed cabbage patch. He talked over his shoulder, gesturing with one arm and holding his gun against his side with the other. Amjad and I struggled to keep up. “He is saying the Americans killed three of his cows last night with their helicopters,” Amjad said. “And they injured another. He’s saying, ‘Did they think they were terrorist cows?'”

Hamza showed us the straight lines of shell prints from the helicopter’s guns. Larger holes showed where heavy mortars had sent plants flying in all directions. I asked him whether it was possible that the resistance had used the farmland. No, he said, he and his family were here all the time. No resistance. Just cows. Men and kids gathered from where they had been working. No resistance, they insisted. They were eager to show me the injured cow, but it was getting late and the cold air and my lingering flu left me feeling wrecked. The three dead cows had already been sold for meat.

Before leaving I asked the men whether they hoped that the newly announced elections would change things for the better in Iraq. It’s a question I asked everyone I spoke to that day. Since the announcement, there’s been worldwide debate as to what it really means. Is the Bush administration using premature elections as a way to cut its losses here and get out? Is it the carrot that serves as complement to the iron stick? Will it make the Iraqis feel as though eventually their country will belong to them again? Everyone I spoke to in Baghdad yesterday, including Lt. Col. Coats, had the same response: They hadn’t heard a thing about elections at all.