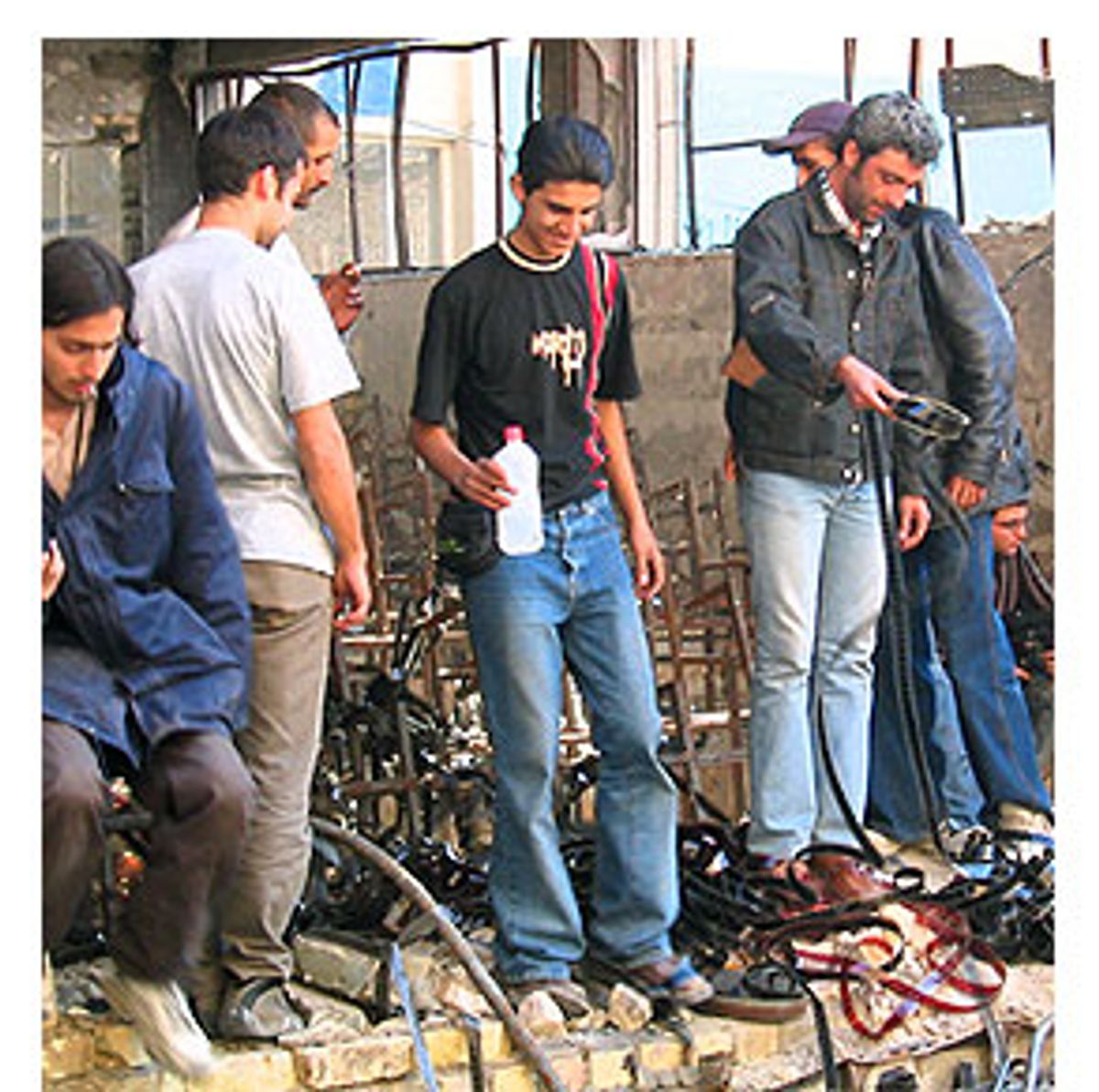

I met filmmaker Oday Rasheed the other day on a pile of bricks that had once been a building in the Baghdad College of Fine Arts. The building's front half lay in fractured chunks of cement and steel on the ground, exposing its stripped interior. Even before asking, I knew it had been destroyed in the postwar bedlam of looting and fires and not by U.S. bombs. It had that particular look that I've come to know well: Not pockmarked or blown out from shells, but pulled down and emptied out by frantic, hungry hands. As Oday picked his way over the rubble to greet me I thought, I'll never get used to seeing these buildings (the National Library, the Baghdad Museum, The National Theatre and hundreds of others) -- never get over the stupidity, both Iraqi (for doing it) and American (for standing by and doing nothing), that led to their literal downfall.

Oday was shooting a scene on the building's wasted remains for the film he is making, titled "Over Exposure," which follows a clutch of characters through the period immediately following the war. I had heard that he was making this film with little equipment and less money. His actors and crew are fellow members of an arts collective, "Najeen" (meaning "survivors") that he's been involved with for many years.

Najeen has been active all over Baghdad since the end of the war. They erected a statue dedicated to freedom in Firdos Square to replace the famous toppled Saddam statue. They performed a collaboratively constructed play within a month of the war's (official) end. They do this work without grant money, without official support. Every day, they pool whatever funds they have, small fistfuls of dinars, and go make art. Now Oday is directing the first Iraqi feature film made in 12 years.

Oday came over to where I sat and said a brief hello. He's 30 and, like many members of Najeen, he wears his hair longer than is customary here. I practically ogled him and the other Najeen members I met. Seeing a dozen guys in one place with long hair and no mustaches deserves a little ogling in Iraq. (When I asked, later, how they dealt with traditional Iraqis who might disapprove of this look, Oday said, "I don't give them a chance to be a stone in my road.") Oday apologized for having to work and I apologized for interrupting him. Then he went back to filming.

I sat on some steps and watched the art director build a small, smoky fire to create the effect usually made by a smoke machine. Imagine: real smoke playing smoke in a film. Nearby, on a half-crumbled wall, another artist in the collective, Basim Hamad, creator of the Firdos Square sculpture, had started an abstract work of art. He adhered ripped paper to still-wet azure blue paint, creating the barest suggestion of a face that reminded me of some Sumerian works of art I had seen at an archeological site. One of the members of the collective saw me looking at Basim's wall and explained to me that it was not part of the film. With art supplies so scarce, Basim makes work wherever and however he can.

Oday was shooting a scene in which a filmmaker character, modeled after himself, surveys the building's wreckage. He rehearsed a shot a number of times with the actor. A simple shot -- the actor lights a cigarette and hefts a broken camera lens. But they went over it again and again until Oday was satisfied that they had it right. He has barely enough film to finish the picture and every second (or rather foot) must be used wisely.

When Oday decided to begin shooting, he e-mailed the people at Kodak for advice. The only film stock that Oday could access turned out to be from 1975. Kodak stopped making the film in 1983. Most of the film Oday uses was originally looted from the Ministry of Culture. The new owners of the looted film sell it to a silver-recovery factory (all unused photographic film contains minute amounts of silver). Oday visits the factory and buys the film before the factory destroys it in order to eke out the miniscule amount of silver from the celluloid.

Oday got a response from Kodak: If you want to do this, maybe you are a fool or a genius but we'll help you. He did a test with the film and sent it to the Kodak lab in Beirut. After developing the film, the lab told Oday he needed to underexpose the film when shooting, due to its age. And so the name "Under Exposure."

Oday didn't really have time to talk while filming so, the next evening, I went to an apartment that he and other members of Najeen use as a headquarters and crash pad. We sat together in the small, unheated living room. I wrapped my scarf tightly around my neck and smoked the cigarettes they offered me in order to prevent myself from shivering.

I started the conversation by asking some slightly stiff journalistic questions about film. Oday answered absently and told me he was feeling very sad because it was the anniversary of John Lennon's death. Other members of the group trickled into the living room and listened and interjected their own thoughts. They spoke poetically about the importance of art. About the fact that, now that the war of guns and bombs was over, a new, even more crucial war was being waged; the war to reintroduce culture in Iraq. Art, they said, could provide the knowledge that would save their nation. At first I thought perhaps they were a little overly doctrinal, speaking in a way they thought artists should speak. But it quickly became clear that I was totally wrong. These guys have spent most of their lives trying to make art in an artless environment. Before the war, they worked mostly underground, outside the system. Even then, they could never have overtly criticized the regime. In their plays, they used music and oblique metaphors to convey the emotion of resistance.

Quite soon, Oday and the others were asking me questions, and I found it difficult to remember to take notes as we began talking about books (e.g. "The Brothers Karamazov") music (from traditional Iraqi to heavy metal) movies (why do so many foreign directors start making crap in Hollywood?) and books made into movies ("Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas"). I had never had a talk like that with Iraqis. It turns out, Oday had never had a talk like that with an American. We each found ourselves embarrassingly surprised at the other's diversity of interests and cultural acuity.

A lot of influences he and the others cited were American, but they don't see America as some cultural grail. They all seemed much more interested in making their work in Iraq than even thinking about going to America. Now, too, their view of America has been complicated by the occupation. "We used to hate Saddam," Oday said, "But we're not able, yet, to be glad he's gone." I found this surprising, given Najeen's new artistic freedoms. But it made more sense when, moments later, Oday described the day he and his brother and other members of the collective tried to stop the Theater and Film Center from being looted. He ran up to a soldier and tearfully asked him to fire shots in the air to scatter the looters. The soldier couldn't, didn't have orders. He tried to calm Oday down, saying, "Chill man, chill man," until Oday left.

Like so many Iraqis -- like me -- they still can't believe what happened in those days. "Ask Americans to make George Bush explain," Oday said to me. "Explain what happened, and why he didn't stop it."

Occasionally, Oday would stop mid-sentence and jump over to the computer in the corner in order to deejay for the rest of us. We started the night listening to Eric Clapton while the accompanying videos played on the computer screen. I'm not a huge Clapton fan, but every so often, a few of the guys would begin singing along. They all sang along to "Tears in Heaven" and it was one of those sweet unabashedly sentimental moments that you just can't argue with.

When the song ended, Oday selected another Clapton video. "You have to see this," he said. The video was rolling some bland moodily lit concert footage. Given the kind of film influences we had just been discussing -- Federico Fellini, Brian DePalma, Martin Scorsese -- Oday's excitement seemed a little misplaced. But he sat, rapt, waiting for one specific moment. It passed so quickly, he had to replay it a few times before I saw. In the background of the shot, a large Panaflex camera, balanced precariously on some equipment, crashes to the floor. We watched the shot over and over and each time the camera fell to its inevitable fate, Oday quietly said, "booom." Finally, he stopped the video. "I would do anything to use a camera like that." He put his hands, half-mockingly, over his face. "For years," he said, "I am suffering from this shot."

One of Oday's favorite films is Fellini's "8 1/2." He's read about it extensively, knows it more or less by heart. He's just never actually seen the movie. There's no way he could have.

Now in Baghdad, you can buy a crappy bootleg DVD of just about every newly released Hollywood film. In the last week, one of my housemates has picked up "Master and Commander," "The Matrix Revolutions, and "Elf," to name a few. I watch them at night on my computer before falling asleep. It's a good way to wind down and give myself over to something besides the tensions and sadnesses of this city.

I lie on my bed and try to block out the racket made by the house generator -- an industrial panting noise that easily penetrates space, walls, and windows. The generator's been on for almost 24 hours straight. We have no idea why the city power has been out so long. It's impossible to guess at the far-off events that dictate its comings and goings. It's like dealing with a sullen teenager. Where have you been? What were you doing? When will you be back? The vibrations from the house generator subtly animate the bottle of water next to my computer, making it look nervous.

In the Green Zone (the massive walled-in area in Baghdad where the U.S. administration, American contractors and some soldiers live, work and hole up, rarely venturing into the rest of the city unless accompanied by massively armed convoys) little kiosks selling bootleg DVDs line the sidewalks now. Iraqis who have houses in the zone sell DVDs, cigarettes, blankets decorated with American flags, kitschy heart-shaped cigarette lighters with pictures of Saddam and George Bush. Iraqi boys -- their sons, perhaps -- ride bicycles up and down the streets with their own stash of DVDs for sale.

These boys are the porn brokers. None of the men who run the kiosks want to risk having the porn on display, offending devout Muslims who might pass by. Soldiers flag the boys down (and vice versa) and flip through their collections, looking for something new. The money the families make balances out what a hassle it must be to live there. If they leave the zone, they have to wait, when returning, in long lines where they are searched for weapons.

In Baghdad, a city roughly two and a half times the size of Chicago, you cannot go to a movie theater and watch a movie unless you want to visit one of the few decrepit cinemas showing Turkish porn. In all of Iraq, in fact, you won't find a single real movie theater. Cinema died here a long time ago. Saddam started the job by putting the good old totalitarian chokehold on any art that didn't serve as a monument to his own glory.

I asked Oday and the other members of Najeen about what Saddam did to culture in Iraq. "This fucking regime," said Oday. "He [Saddam] broke the society." The way Oday sees it, every country has villages and cities. When people from the villages go to the cities, their mentality undergoes a certain change. The culture and loosening of traditional strictures evinces a shift in their thinking, opens them to further experience. But Saddam was a village man who, along with his cronies, came to the cities and made them into villages. He forced the most narrow-minded of rural sensibilities onto a sophisticated populace and slowly, slowly, shrunk its worldview to match his own.

Oday grew up searching out access to books, films, music, movies. How did he get hold of music before downloading off the Internet made it so easy? I asked. "Oh man," he said, "you can't imagine. It took me four years to get the complete Beatles."

Now in Iraq, you can theoretically write, paint, watch, hear whatever you want. But it isn't happening yet. There's been no explosion of books, films, plays, poetry. And in a country with shortages of power, medicine, potable water, safe streets, there hasn't been much focus on filling the libraries. (When I told Oday I had a DVD of David Lynch's "The Elephant Man" that he could borrow, he jokingly got down on his hands and knees and bowed.) In the meantime, Iraqis get a heavy dose of American pop culture at its worst through DVDs, satellite TV channels, and the Britney Spears et al. pop that plays on many radio stations here. Oday sees this as a critical time, in terms of reintroducing culture to their country. And he and his comrades are going at it with whatever they have.

"It's like the country has been in a locked jail cell for 30 years," he said. "We're still blinking from the light of the sun."

Shares