Over the years, Michael Caine has played everyone from Cockney womanizers to Oxford professors to New England doctors -- and, heck, he's even played Austin Powers' father -- but in Norman Jewison's "The Statement," this great man of the modern screen plays something he's never played before: a French Nazi.

Even Caine admits that the role was "a bit of a stretch" for him. But Jewison says that as soon as he read the script, he thought of Caine for the role of Pierre Brossard, an old religious zealot on the run from what appears to be a group of Canadian Jews hoping to kill him to avenge the cold-blooded murder of seven Jews during World War II. (Tilda Swinton and Jeremy Northam costar as a judge and a colonel, respectively, who are trying to track Caine down before his would-be murderers do.)

"I immediately felt that he was the only one to play this, because he's such a confident actor," Jewison says. "Brossard is not an important man. The people manipulating him are important, but he himself is a failed individual. Bigoted people, who hate people they don't even know, are very small people. They're very sad. And I knew Michael was someone who could really bring that out."

Caine recently sat down with Salon at a New York hotel to discuss his role in "The Statement," his long acting career, his rocky relationship with the British press, his knighthood and, oh yes, his aversion to nudity -- his own or other people's.

I was just talking to Norman Jewison about you ...

Hello! Did he say lots of bad stuff?

He said great stuff. He was talking about your courage in choosing this role.

It wasn't particularly courageous. What it is, is it's my fascination with doing tougher and tougher work and testing myself. Because, I mean, I can play a Cockney gangster in my sleep, you know. But to play a French Nazi, that's a bit of a stretch. It's not exactly my normal, everyday life. And so I give myself these difficulties and then I have little treats, like I play Austin Powers' father or do "Miss Congeniality" or Batman's guardian [i.e., Bruce Wayne's butler Alfred], which is my next thing. I think to keep audiences interested over the period of time that I've managed to, I first of all have to interest myself. I can't just get up and say, "Oh, I'll churn out this same old boring thing, I'll get a few quid, I'll make some money and I'll go home."

You know, I'm 70 years old. I have to get up at 6 o'clock in the morning and go do a load of rubbish with a load of people I don't like. I do it to stimulate myself. One of the next things I'll do next year is a remake of a picture I did called "Sleuth" with Laurence Olivier. I'm going to do that with Jude Law. And I'm going to play Olivier's part, obviously. I'm the older man. That's what I do. It's a challenge. Everything's a challenge, and I like it.

So you chose to play Brossard because it was something you hadn't done before?

Well, and also I think it was the message, as it were, in "The Statement." This whole generation of young people, I think, every now and then, we should give them a little jog and a reminder about things. I don't think it hurts. Because, you know, I was talking to some of my youngest daughter's young friends, and I mentioned Bette Davis, and no one had ever heard of her. It's like, wait a minute. You have to be aware that it all goes by and you think everybody knows what's going on and they don't.

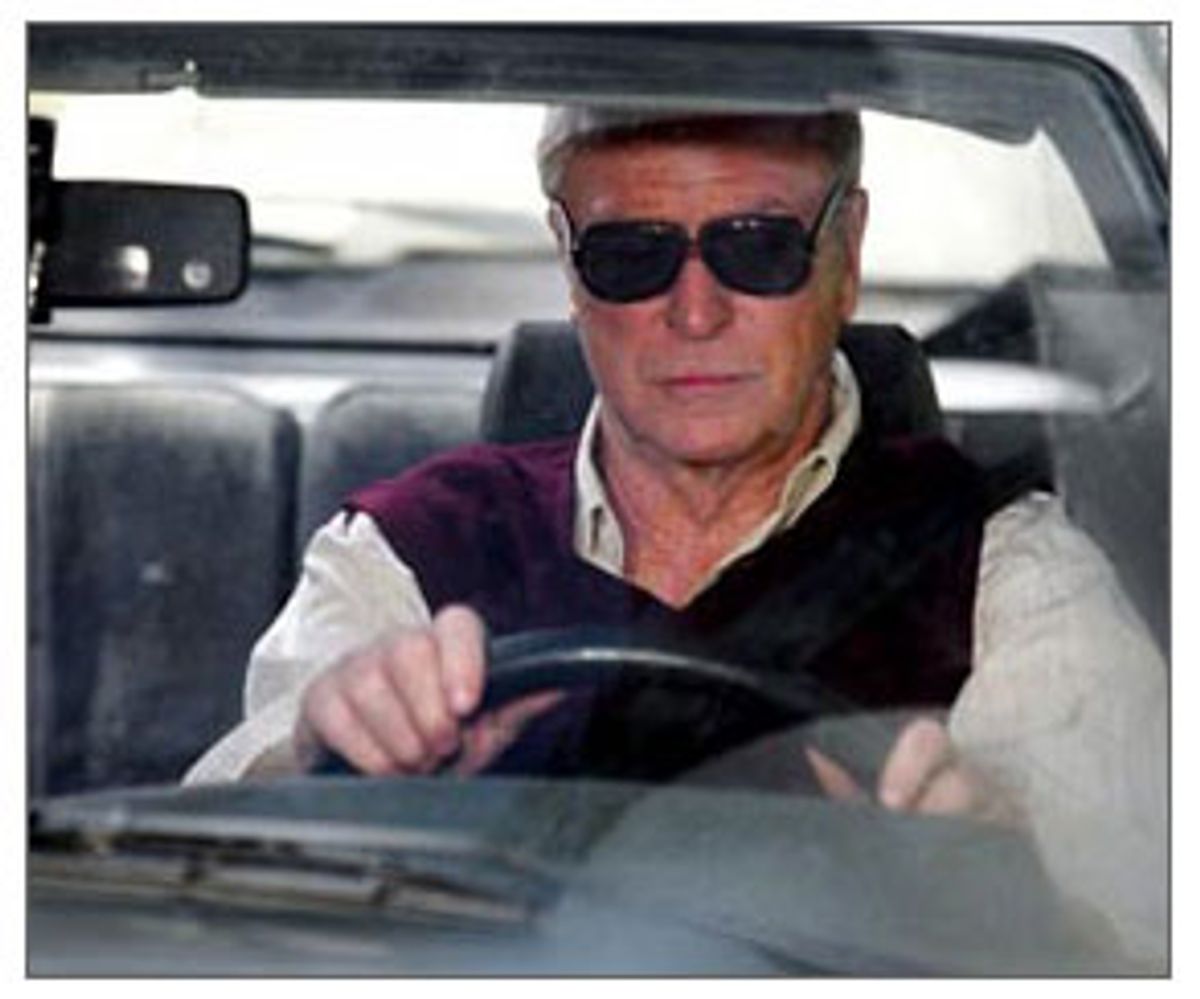

Plus, you have a very good script from a very good book and, from a movie point of view, a chase-thriller in a way. The only thing is, it's the slowest chase in the world with an old guy in a rental car. [Laughs.] It's a chase at 48 miles an hour!

Yes, it is sort of slo-mo for a chase movie. What about how unsympathetic Brossard is? Obviously, you've played all sorts of different characters. Is it more interesting to play an unlikable character?

It's more interesting, but it's also more difficult. I've never played someone who I've disliked so much. It's usually a bit of gangster who's a bit funny and sometimes his villainy is amusing, you know? There's always a bit of a funny side to everybody. This is the first person I have ever played to whom there is no funny side whatsoever. There's not a laugh, a titter; there's nothing. He's just totally unlikable. And my only fear was that, being as it's me, I would engender some kind of sympathy for a character like this. I think people like him are pathetic and sad and so that's what I made him.

But a couple of people I talked to said, "Well, I know he's a scumbag, but I kind of felt sorry for him." And I said, "Well, it's because I made him pathetic. Also, he's a fugitive, on his own, and it's a natural human instinct to go with the loner being hunted. Plus, he was sick; he had a heart condition." You just take the "sympa" off, and he's pathetic. He's pathetic without sympathy.

Plus, he kicked the dog. Killing people is one thing, but kick a dog and the audience will never forgive you.

That's the thing. He kills these people and they go, "Boy, what a scumbag." And then he kicks a dog and "Jesus! What a --! How terrible!"

Do you feel like you learned anything about yourself making this film?

I got a surprise that I've never had before in a movie. Because I disliked the character so much, I developed a kind of selective amnesia. At the end of each day, I couldn't remember what I'd done with it. At the beginning of the day, I knew exactly what I was going to do, obviously, as one would. But I couldn't remember. And at the end of the picture, I couldn't remember any of the performance at all. I think I tried to switch myself off. I think there was a sort of guilt in having played it at all, you know? And then I went and saw the movie, and I realized for the first time in my life what it's like for someone to sit there and watch Michael Caine on screen doing something.

Because I've never done that. I always knew what was coming. You know, you usually say, "Well, there was this scene where I did this and I wish I had done that." This time, I didn't know what was coming, couldn't remember a single thing. And I was very happy because I never saw me. All I ever saw was Brossard. I saw the character and that was it. So I was happy with what I had done. He worked. You believed he was who he was, and that's all I can do as an actor.

I understand it's common for British actors to work from the outside in, as opposed to American actors, who tend to work from the inside out. What is that process like for you? Do you simply layer on a role?

Well, in this case, I'm quite a big guy, and I wanted him to be a small man. And I wanted him to look harmless. His clothes we took from newsreels of middle-aged French men who made pilgrimages to Lourdes. That's how they were all dressed, in that very cheap clothing. I had them make it one size larger, so that I looked smaller and then bent myself over, round-shouldered, very furtive and small and pathetic. Start there.

Then you go into sense memory -- I was trained in Stanislavski, and sense memory is everything with that. Brossard is a man of incredible religious beliefs. I mean, extraordinary. I had no experience of extraordinary religious beliefs, but I had believed in other things extraordinarily. I've known great fear, tremendous fear of death. So I have all these things in my background that I could use. Also, there's an insanity to religious zealots, and I've played many psychopaths before. That I've figured out.

I've known many religious zealots of every religion as well. My own religious background is I'm a Protestant, a Church of England Protestant. My father was a Catholic, my mother was a Protestant, I was educated by Jews and have a Muslim wife. So I'm very eclectic about religion and I've met zealots of all of them. And there's always a slack madness about it.

Do you feel that the movie was saying something that makes it particularly topical now, given what's going on in the world?

We did a Q&A after the showing last night with Norman, me and the producer, Robert Lantos. Norman isn't Jewish and neither am I. Robert is. And someone in the audience said, "Are you Jewish?"

He said, "Yes."

"Well, why make a movie about the past?"

He said, "It isn't a movie about the past. Unfortunately, it's a movie about the present. It's a warning. It's a movie about the could-be future."

That's what Robert said, and that's what I felt about it, but I didn't feel, from a religious point of view, able to say things like that. Even doing interviews on a picture like this, you have to be very careful what you say because -- do you have the right to say those things? You know what I mean? I mean, I can't speak as a Jew from experience, but I know the entire thing, and I'm here partly because of that, out of sympathy for it.

You've talked about how you keep fresh by taking all different sorts of roles. Why do you think so many actors get stuck in a groove and typecast?

It's a movie-star thing. Some people think they're movie stars and some people think they're movie actors. I think I'm a movie actor. The difference between a movie star and a movie actor is a movie star gets a script -- movie star Michael Caine gets a script and he says, "Now how can I change this script. It's not quite Michael Caine. I've got to change it." And they say things like, "Michael Caine wouldn't wear that kind of thing. Michael Caine wouldn't say that to a girl. Michael Caine wouldn't drive that sort of car. So we'll have to edit the script." And everyone says, "Oh, of course, Michael, we'll change all that." They change the script to suit them. A movie actor, he changes himself to suit the script. He wears glasses, puts on a fat belly, gains weight, loses weight, grows a beard, moustache, any bloody thing.

A supreme example of that for me was when I did "Sleuth" with Laurence Olivier, who was one of the greatest actors in the world. We rehearsed and he was screwing up, badly. We were very worried, because there were only two of us in the movie, but no one said anything. And then one day, Larry came in with a moustache, and he put it on, and he was fantastic. And at the end of the day, he took it off and he said to me, "Do you know, Michael, I cannot act with my own face." And he couldn't. You see Olivier in anything, he puts on a bloody nose, a wig, something. He doesn't look like Larry. Unbelievable. And that's one of the greatest actors in the world.

I wanted to talk to you a little bit about the stuff you won't do. Like nudity.

Yeah, I never do that. It wasn't rife when I was young enough for anyone to want me to be doing that. And now nobody wants to see me doing that anyway. But I always remember a story about when "Oh! Calcutta!" first opened in England, which was the first stark naked musical with men as well. You know, there'd been striptease before with women, but this was the first time with men. They asked Robert Helpmann, who was then the director of the English ballet, "Would you ever do a naked ballet?" And he said, "No." They said, "Why not?" And he said, "Everything doesn't stop when the music does."

So that's my point. It's ridiculous. If you are an actor and you come on with nothing on, you're doing a speech, no one is looking at your face. They're not necessarily getting excited about it or getting off on it or doing anything. Other men will be looking purely out of curiosity, comparing themselves. But they are not looking and listening to you. I've gone down there, I've got my face made up, I've learned all this bloody dialogue and no one's listening, no one's looking. They're looking at something that's got nothing to do with the plot. And it doesn't stop when the music does.

Do you think there's ever a time when nudity on film or on the stage is justified or necessary?

If you do it outright, right out. There's the famous case of the L-shaped sheet. Where the man is sitting in bed and he's covered to here [gestures to waist] and the woman's sitting next to him and she's covered up to here [gestures to chest]. The sheet looks like an L. And then you've got the other one where the woman's sitting in bed with her husband, she's been married to him for 20 years, there's no one else there, and she's holding the sheet over her breasts. What for? You know what I mean? So I'm trying to give a great performance, which is based on honesty, and the whole bloody thing's dishonest right from the start.

Then there's the atmosphere on the set. Even if you're not nude -- as a man, obviously, a lot of the time you're not -- if the girl's gotta be topless or something, well, a lot of actresses are terribly upset about it. And it's very wearing on the set to have someone bursting into tears and rows and things: "It wasn't in the contract. I never agreed to ..." And you're going, "Shit, what is the point?" Just from a practical point of view. And also, all right, if you're an actor and you've got all your clothes on and the girl's got nothing on, who the hell's looking at you when you're talking? They're all looking at the girl! They're looking at the naked body!

I didn't realize that not only would you not do nudity, but you'd rather not even be involved a scene with someone who is.

I don't want the girl to do it! No. Because they get nervous. It's a nerve-wracking thing: Clear the set!

Plus it's a creepy double standard.

It is. It's terrible. I don't like it.

What about your comment at the BAFTA awards a couple of years ago, when you got the award for lifetime achievement and you said you felt like an outsider in your own country?

It was a press thing. I had just been slaughtered for "The Cider House Rules" in England the week before, critically slaughtered. And I can't say I was shocked at the English critics, because they've always slaughtered me. But I hardly won any awards at all for "The Quiet American," and for the first time in my life I won leading actor from the British film critics. So I can't grumble, but it's just that was the week "Cider House Rules" came out. And I have a history ... I mean, I started off getting the worst reviews you've ever seen for "Alfie" [his first major role, in 1966] and right the way through, I've always been criticized badly.

I've always worked for and with Americans, and if you are English -- and obviously, I come from the working class -- there's an extraordinary freedom in coming here, where people judge you for what you are and don't prejudge you just because you've opened your mouth, because a lot of this judging is quite insulting if you've got a Cockney accent. It's not just, "Well, he's come from a very poor family." It's that you're stupid, unintelligent, unskilled, whatever, you know? That reflected itself a great deal in the British press with me, over a long, long time. I thought everybody realized that, but of course, everybody hadn't read the press. So that comment at the BAFTAs caused an uproar, but every time I've opened my mouth in England I've caused an uproar about something.

There have been other instances?

I remember the last big uproar. I did an interview with a woman from the New York Times over the phone. We'd just lost the World Cup in football, in soccer, and during the course of this long interview, she asked, "How do you feel about losing in the World Cup, eh?" One line! And I said, "Well, it's OK. We're England. We're used to it. We lose all the time." Headline the next day in the paper: "Michael Caine tells America the British are losers." They attacked me for five weeks every day in the press. One sentence.

How about the knighthood, then? What does that mean to you? How does that feel?

Fantastic. It's the recognition of a life. I thought it was great. I loved every minute of it. I love being a knight. I never insist on anyone calling me "Sir." That's not the point of it. And I especially wouldn't insist on it in a foreign country where there isn't any knighthood. I suppose if I went to court and was introduced, I'd say, "Well, I am Sir Michael, if you're going to introduce me in those surroundings." But you can't use it if you to go to the jungle and say to an African, "I'm Sir Michael Caine." He'd say, "So what?"

If you've felt so frustratingly out of place in the U.K., why didn't you move to America?

I did. I moved to L.A. for eight years. And then I went home. I got homesick. It never rained or anything in L.A. It was never cloudy. There was sunshine every day. There's no weather. I got homesick for the weather. So if I ever left England again, I'd live in New York. I would have to. I relate to a big city. I was born in London.

But you have a whole world there. I understand you're really into gardening.

Oh, me. I have a house inside a 200-year-old barn. My daughters, they don't live with me, but they have their own guest apartments, which they designed themselves. Everybody's got their own space. And then there are marvelous public spaces and there's a wonderful new cinema. I just spent $60,000 redoing my cinema with the most brilliant DVD system, and first they tell us that we're not going to get the screeners for the Oscars and then they send us videos. I wasted all that money!

Speaking of regrets, is there anything you haven't been able to do that you'd really still like to?

I never won a leading Oscar. I have two Oscars. They're both supporting, which is very nice. But I've been nominated four times for a leading Oscar and you get fed up sitting there losing, you know? I keep sitting there with that smile on my face, that same sickly smile, saying, "Well done!"

Do you feel like this role might do it for you?

This is too unsympathetic to win anything. It's very unsympathetic. You look at the history of Oscars, it's always sympathetic people who win.

Shares