It's a good bet that, despite their apparent elation, many U.S. leaders wanted Saddam found dead, not captured alive. As they ponder the consequences they're probably increasingly upset that the disheveled fallen dictator wasn't riddled by a hail of bullets, blown up by a grenade, or self-dispatched by cyanide capsule when all seemed lost.

Instead, prominent Americans could find themselves playing a role in what may be a very long, drawn-out and embarrassing trial. Imagine, for instance, seeing Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, former Presidents George Bush and Bill Clinton, and a parade of CIA directors and secretaries of state called as witnesses -- for the defense. Not to mention a clutch of headmen from other Western and Middle Eastern countries. This may be exactly what Saddam now craves: the chance to publicly implicate other leaders and countries in his own brutal past. It won't be difficult.

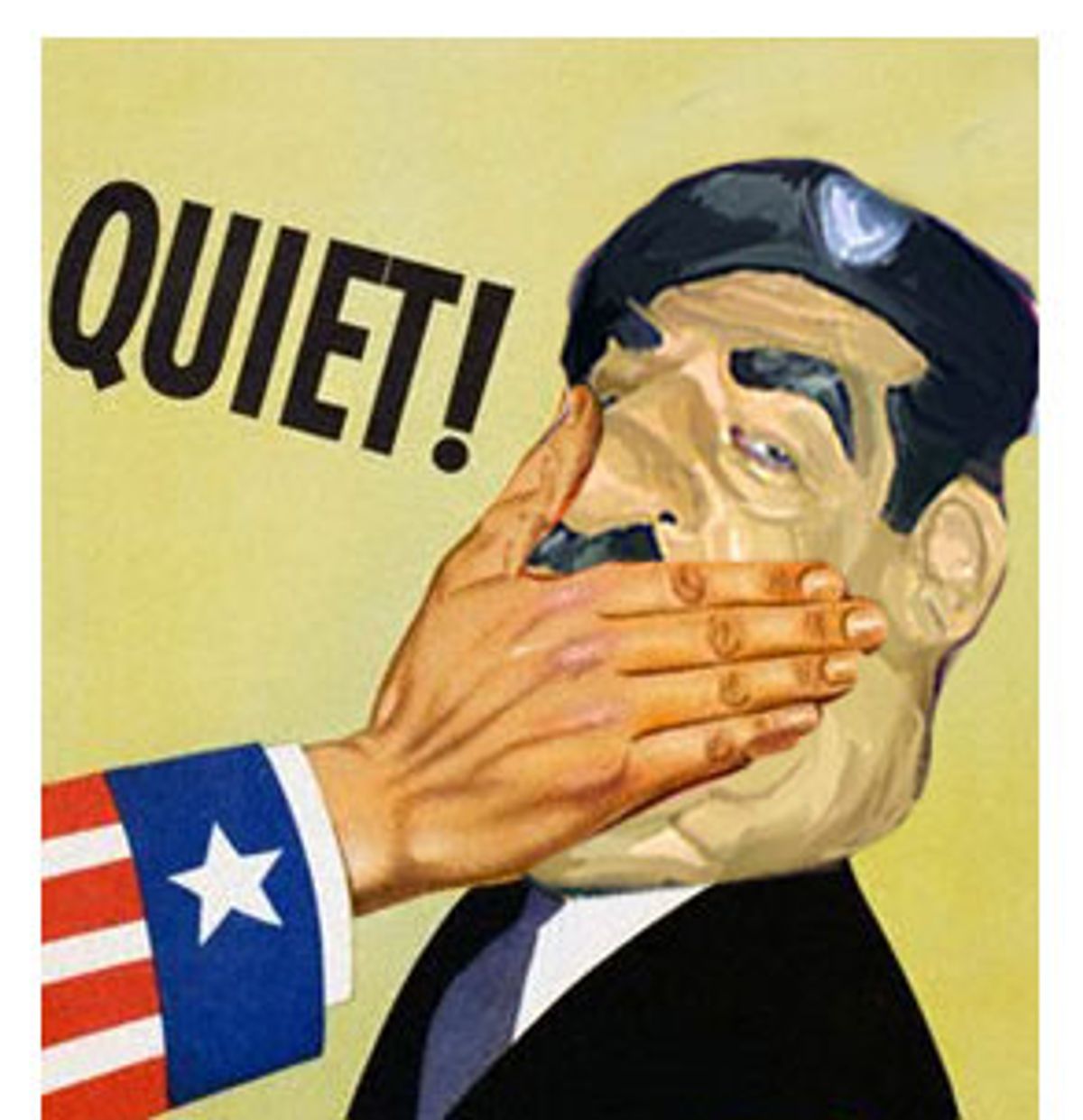

Some of the tawdry background about Saddam's ties to world leaders has trickled out in the press over the past year, but tied together during a dramatic trial, the collateral damage could be devastating. Saddam's attorneys could present an interesting dilemma to Washington, demanding access to U.S. government documents detailing its leaders' dealings with Iraq, documents that would almost certainly implicate other nations as well. The New York Times' conservative columnist William Safire speculated Monday that Saddam "is looking forward to the mother of all genocide trials, rivaling Nuremberg's and topping those of [Nazi Adolf] Eichmann and [Yugoslavia's Slobodan] Milosevic. There, in the global spotlight, he can pose as the great Arab hero saving Islam from the Bushes and the Jews."

Of course Saddam is no hero, but he may have evidence showing that when it comes to Iraq, many American leaders haven't exactly been heroes, either.

Saddam and his attorneys might begin with footage shot back on Dec. 20, 1983, by an official Iraqi television crew when Donald Rumsfeld arrived in Baghdad as special envoy from President Ronald Reagan. Saddam, wearing a pistol on his hip, already had established himself as a brutal dictator -- as Newsweek put it, "a murderous thug who supported terrorists and was trying to build a nuclear weapon." According to the official note taker at the meeting, Rumsfeld "conveyed the President's greetings and expressed his pleasure at being in Baghdad" to the murderous tyrant.

At the time, of course, America's chief concern was Iran and its Ayatollah Khomeini, with whom Iraq had gone to war. And so, over the next five years, until the conflict finally ended, the United States supplied Saddam with economic aid and such nifty items as a computerized database for his interior ministry, satellite military intelligence, tanks and cluster bombs, deadly bacteriological samples, and the very helicopters that were used by Saddam to spew poison gas over his own Kurd citizens. And when those atrocities finally became known, the Reagan administration also lobbied to prevent any strong congressional condemnation of the Iraqi dictator.

Fast forward to 1990 and the invasion of Kuwait, a territory that, according to some interpretations, had once been part of Iraq. In that year, Assistant Secretary of State John Kelley called Saddam a "force of moderation" in the Middle East. Saddam, in fact, moved into Kuwait only after consulting with the ranking U.S. diplomat in the region, April Glaspie. So why shouldn't the fallen dictator's attorneys now summon Glaspie and her State Department masters to explain why she assured Saddam back then that the way he handled his border dispute with Kuwait was of "no concern" to the U.S.?

Following Saddam's defeat in 1991 came the brutal repression of the Shiites. Tens, maybe hundreds of thousands of Shiites were massacred by Saddam after they rose up against Baghdad with U.S. encouragement. Saddam will probably argue he had no alternative to keep his splintered country intact. And he can point out that the same fact occurred to the Americans, who cheered on the Shiite rebellion and then turned their backs after they began worrying what might happen to Iraq if Saddam were to fall. During the trial, Saddam could ridicule as hypocrisy the shock recently expressed by American leaders as grisly evidence of his mass executions was uncovered. It's hard to believe that U.S. government files would not contain desperate pleas from the Shiites for help as their followers were herded to their graves.

A similar fate, for similar reasons, befell the Kurds, who received U.S. encouragement to seek independence under presidents from Richard Nixon to Bill Clinton, only to be abandoned. The Kurds never seemed to learn. The U.S. had left them to Saddam's bloody reprisals in 1975, prompting Henry Kissinger's famous explanation that "covert operations is not missionary work."

As for Saddam's quest for a nuclear weapon, the former dictator will point out that, if weapons of mass destruction in the Middle East are a concern, they exist in Israel and Pakistan as well. Maybe here the French could be brought forward to testify how they helped both Iraq and Israel with nuclear facilities. A host of other suppliers in the WMD field, from Germany, Italy, the U.K and the U.S., would be subpoenaed. And Saddam's lawyers might want to investigate the old charges that Vice President Dick Cheney's firm, Halliburton, violated sanctions against Iraq and provided it with oil-industry equipment. (Cheney, it will be recalled, lobbied to end U.S. sanctions against Iraq while he headed Halliburton, arguing they hurt companies like his more than dictators like Saddam.)

None of this makes Saddam innocent of his barbaric crimes. But it certainly muddies the moral waters and gives the former dictator and his supporters much more than their day in court. Which is why you know a lot of people in Washington wish Saddam had used that loaded pistol he kept in the "spider hole" where he was finally captured. But true believers in Iraqi democracy have to be glad he didn't.

Shares