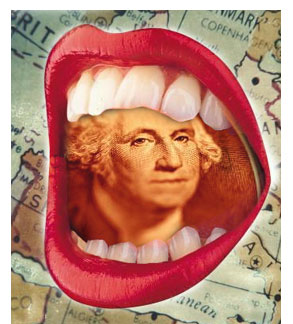

As transatlantic bickering continues over Iraq, there’s talk of America and Europe drifting apart. Washington’s ruling party policymakers shrug at the thought. Good riddance. Who needs “Old Europe”? But if the political feud were to spill over into economic relations, the results could be devastating to Europeans and Americans.

While America’s global military superiority is unmatched and unchallenged, its economic might is not — something that many of those around President George W. Bush obviously fail to understand.

The ties between America and Europe have never been as tight, intertwined and vital to the peoples on both sides of the Atlantic as they are today. “The sooner opinion leaders on both sides of the Atlantic recognize just how entangled and interdependent the transatlantic economy has become, the sooner they will realize what is at stake and the stakes, indeed, are huge,” write Joseph Quinlan and Daniel Hamilton of the Center for Transatlantic relations in Washington.

The largest part of U.S. corporations’ overseas profits come from Europe. American subsidiaries in the U.K. alone employ more workers than they do in all of developing Asia. The amount of American money invested in Germany — $300 billion — is greater than total U.S. assets in all of South America. And despite all the talk about NAFTA, in the 1990s American firms sank nearly twice as much money into minuscule Netherlands as they put into Mexico. In 2000 the sales of U.S. affiliates to China were just one-quarter what they sold to France.

And despite all the bluster from Washington over the last year about punishing France and Germany, U.S. investments in those two countries actually soared. Why? Because, though there may be plenty of grumbling about traitorous Europe in U.S. corporate boardrooms, when it comes to pragmatic decision making, it’s clear that Europe is still a much more attractive and lucrative overseas market than just about anywhere else on the globe. That’s where the consumers are. That’s where the profits are. And the best way to grab a slice of that market is not to export, but to go there and set up your own plants.

But that’s only half the story. While American firms are flocking to Europe, European firms have been pouring even greater amounts into the United States. For the same reason: to exploit a huge and highly profitable market. Many of Europe’s largest firms are more at home in the United States today than in Europe itself.

Already by 2000, Europeans held a whopping $3.3 trillion in U.S. assets, representing two-thirds of all foreign assets in the United States. Europeans have invested more capital in Texas alone than Americans have invested in Japan. And over the past year, while European and American leaders were slinging barbs across the Atlantic, European investment in the U.S. continued to soar.

Not least of all from the vilified French. Despite rabid anti-France rhetoric on bumper stickers, T-shirts and Fox News, despite “freedom fries” in the Senate restaurant, and “Freedom toast” with whipped cream on Air Force One, over the past year, the French were the second ranking foreign investors in the U.S. stock market — and No. 1 in direct investments.

There are now some 2,500 French subsidiaries in the U.S., all of which, of course — along with the capital pouring in from other European countries — provided a vital boost to the U.S. economy, and tens of thousands of new jobs for Americans. European subsidiaries in the United States employ more Americans than American subsidiaries do in Europe.

Which is one reason why those Americans pushing for a boycott of “French” products have had such a tough time. Even if a patriotic consumer wanted to punish cowardly, money-grubbing “frogs,” he’d have to be a committed student of mergers and acquisitions to spot tainted Gallic products.

Liquor: Stay clear of Dom Perignon, right? But what about Seagram’s, Royal Canadian, Glenlivet, Wild Turkey Bourbon, Jacobs Creek Australian wines (all owned by France’s Pernod Picard)?

Magazines: Woman’s Day, Car and Driver (France’s Hachette Group). Soft Sheen Black Hair Products, Helena Rubinstein, Giorgio Armani (L’Oreal), the Athlete’s Foot (Group Rallye). The First Hawaiian Bank (BNP Paribas), RCA TVs and DVDs (Thompson), Motel 6 , Red Roof Inns (Accor), Nissan, which just built a giant $1.4 billion plant in Mississippi (Renault), Uniroyal Tires (Michelin), Taylor Made Golf Clubs (Adidas-Saloman).

Good old American entertainment? Smokey Robinson, Stevie Wonder, Motown Records, MP3.com, Polygram, the Sundance Channel, Universal Studios (all belonged to France’s Vivendi until the flailing company recently shucked off its U.S. entertainment interests, a move that had nothing to do with politics. Vivendi, however, still runs the water system for cities like Indianapolis).

You could always hire a consultant from Ernst & Young to guide you through the tangled skein of corporate ties, but beware: Ernst & Young is also French-owned (Cap Gemini.)

O.K. But what about France’s flagship product, fine wines? Surely the boycott must have had some effect there? But it turns out the dollar value of sales of French wines rose 8 percent over the past year. According to trade officials at the French embassy in Washington, there seems to have been no serious economic reprisals, to date, despite early fears. “At one point there seemed to be kind of a brush fire, but it didn’t last long.” Any decline of French (and other European) exports to the U.S. has much more to do with the increased value of the Euro, rather than the would-be boycott.

The Pentagon’s recent announcement cutting French and German firms out of lucrative Iraq reconstruction products may be one final attempt to exact vengeance. The irony, however, is that in the United States itself a key customer of French subsidiaries is the U.S. government and the Pentagon. The huge French catering firm Sodexho, for instance, is paid over a hundred million dollars a year to feed U.S. Marines, at every one of their American bases. That eight-year contract was denounced last spring by a clutch of furious congressmen. They backed down when they realized that ending it would cost American, not French, jobs. Sodexho has 130,000 employees across North America.

That’s for starters. Aerospatiale provides helicopters to the U.S. military and Coast Guard, while Dassault sells Falcon 20’s to the Coast Guard. The American subsidiaries of France’s Michelin supply the Pentagon with tires for everything from advanced fighter aircraft to tactical wheeled vehicles, not to mention sales to NASA for the Space Shuttle.

But just as important to the U.S. as the hundreds of billions of dollars in French — and European — investment is the European willingness to bear the brunt of the declining dollar and rocketing U.S. debt. The U.S. government is borrowing over $1.4 billion a day to finance its current account deficit. Much of the lending comes from Europe.

But what would happen if, say, Europeans became more interested in pouring their capital into Eastern Europe or China. What would happen if they were to lose faith in the dollar? If they were to reduce or suddenly stop investing in U.S. treasuries and the S&P 500? What would happen if all the blithe rhetoric by American leaders — all that talk of punishing “Old Europe,” and shrugging off worries of a split between the United States and Europe as trifling — actually provoked a breakdown in economic relations between Europe and the U.S.?

A lot of questions for the folks on top in Washington to ponder.