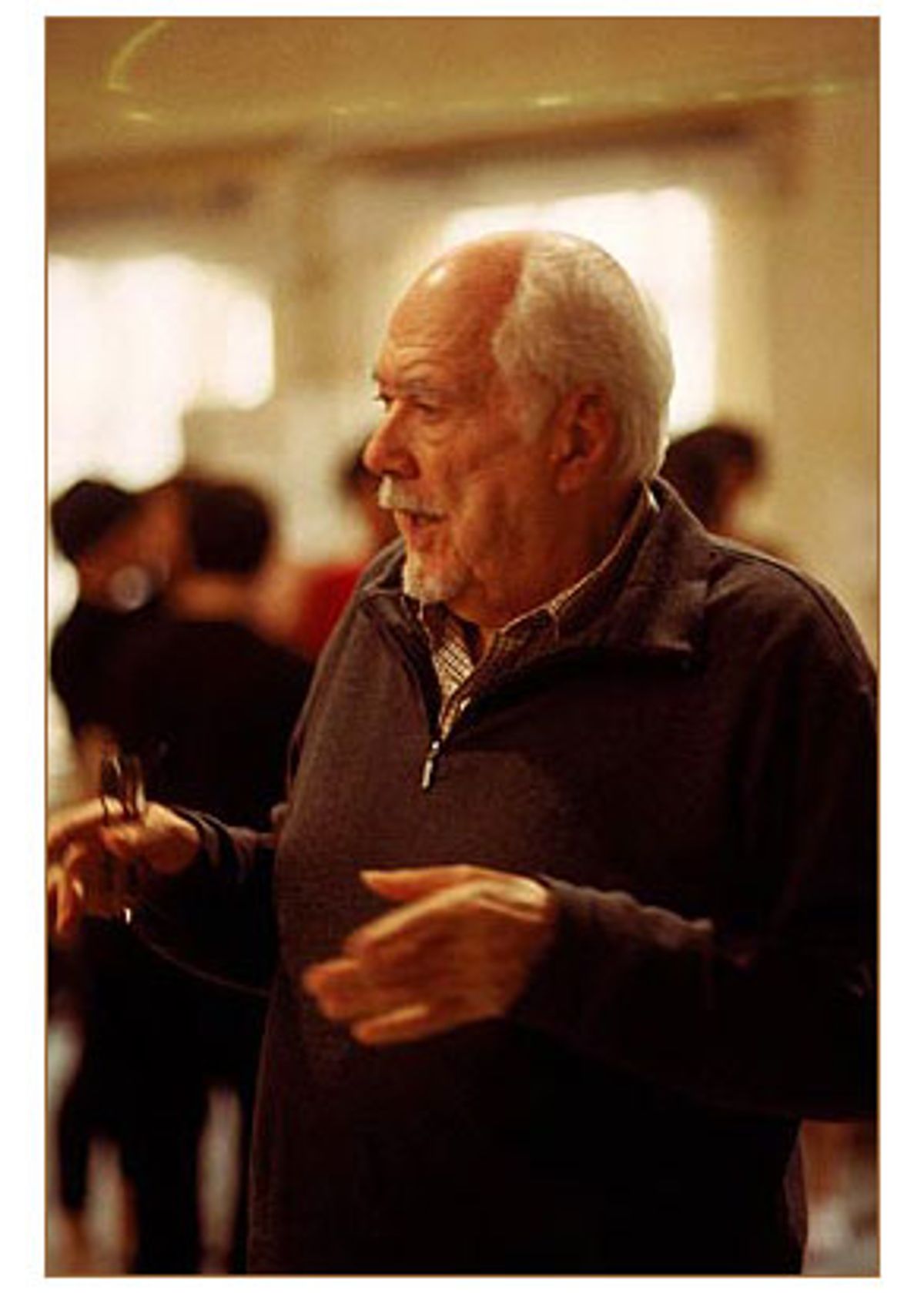

Director Robert Altman has taken audiences into the meticulously detailed, utterly alien worlds of Korean War doctors ("M.A.S.H."), wannabe country singers ("Nashville"), Hollywood power brokers ("The Player"), fashion ("Ready to Wear"), and mid-20th century British upper-crust ("Gosford Park"). But even he admits that his new film, "The Company," was a stretch.

"I didn't know anything about the ballet," he says, adding that when he read the script, "I didn't understand a word of it." All of which seems to have made the project more appealing to the 78-year-old Altman, who appears to relish throwing caution to the wind.

He likes, for example, to be naughty. In the New York hotel room set up for our interview, two armchairs have been arranged in a conversation-conducive configuration in one corner, but the drapes have been pulled and the dark room is dominated by a king-size bed, which, for some mysterious reason, has been turned down. When Altman enters, he gleefully exclaims, "Well, look at this!" before eyeing this reporter. "Is everything fair game in this interview? I could pull an Arnold! I could grope you!"

Gently rebuffed, Altman sinks into his chair and assumes an avuncular air. In the past, though, he hasn't always been able to charm his way out of his salty off-the-cuffs. His quips to the British press about the post-Sept. 11 flag-waving fervor at home included, "When I see an American flag flying, it's a joke," and calling George W. Bush "an embarrassment." Scolds at the Wall Street Journal and Fox News and others like Oliver North took aim. This followed his unfulfilled promise in 2000 that "If George W. Bush is elected president, I'm leaving for France."

Altman talked with Salon about why he made those comments, as well as the difficulty his new movie will have in reaching the coveted teenage boy demographic -- "It's not gonna get any 14-year-old boys, unless they're gay" -- and the less subtle pleasures of watching ballet ("It's a fuckfest!").

What inspired you to make a film about the ballet?

[His screenwriter Barbara Turner] called me and said she'd written a script and would I read it. And I said, "Well I'm very busy now and I don't read well, and anyway, what I think of the script doesn't have any bearing on what other people would think of it, but I'll try." Then she kept nudging me. Finally I read the script, and I didn't understand a word of it. I said, "I don't even know what this is. What are you talking about?" I was supposed to do another film at that time, and I said, "Well, I just can't do it. I don't know anything about ballet and it's just not really right for me."

And then I got thinking, should I just do things I already know about? I'm getting a little bored. And I thought, that's just what I should do, I should jump into the abyss. So I called the abyss back and jumped. I went in as blind as you could be.

You collaborated closely with the Joffrey Ballet in Chicago, which really stars in the movie. Were you surprised at what you found in that world?

I was constantly surprised, and I was also moved emotionally and motivated and humbled by these dancers and the dedication that they had. They just amazed me. And there's a melancholy about it because you realize that at 35 they're finished. Actually at 18. These girls start at 6, and then suddenly at 18, they look back, and they now walk like a duck and their whole social intercourse with people is totally changed because they can't have a relationship with someone who can't accommodate their regime. And yet they can't give it up because it's something they've done all their lives. Then at a certain point, they start teaching kindergarten kids and 8-year-olds to dance at Long Beach or someplace. I just find it very sad. There's no chance that any of them can make any money out of it or get any security. Most of them have double jobs anyway. I kind of fell in love with them.

Did you intend to contrast the pain of the artist and the beauty of the work?

I don't really know. I didn't set out to do anything in particular. I just kind of jumped into this world and what I was saying to myself and to everybody all the time is that what I wanted to do was to get around behind them, to turn over rocks, look under the rocks and see what's there, not just what they show people. You know, it's very two-dimensional, the dance. You sit in the audience out here and the dancers are up there and you don't see behind them. If they didn't turn around, they could have clothespins holding their costumes up. So I wanted to three-dimensionalize it.

And also, it's very sexy. Oh yeah. I mean, these people are buck naked out there! It's like they spray a little thin suit on. These guys sit there with these [he gestures down in front of himself] big packages in front and the girls are [pauses] well! That's why I think all these rich old men support the ballet. Their wives get into it, and they say, "Oh, I'll do it! I'll put my bow tie on." They sit there, and all these pas de deux are all about sex. It's a fuckfest! But that is an enormous part of all choreography. And it's really interesting.

You definitely address that in the film, and how the dancers carry that sexuality with them offstage as well.

It becomes so incestuous, they can't really penetrate or allow the outside world to penetrate them because you couldn't have a relationship with the schedule that they have. So they tend to start carrying on with each other. Half the male dancers are straight and half of them are gay -- that's just an arbitrary guess. So these girls, they come in, and they get with the straight ones, the lifters. That's the one they're having all their touchy-touchy stuff with. So they fall in love with one of the lifters and they become an item. Then they're so together all the time that there's almost no way that can endure. There's a couple of married couples that dance, but it's rare that they stay together.

How long did you have to prepare for this film?

We shot only about 33 days, but I spent a couple of months with the dancers every day. There are 44 of them in the film, and I had a private interview with each one of them. Then I just started hanging out with them. And, of course, Neve [Campbell, the star of the movie] was working with them too.

She was a dancer in her childhood. But now she was coming in as this Hollywood actress ...

If she had come in like a diva, it never would have worked. But when I saw the dancers, Neve would just be in there. She'd be sitting on the floor with them when I'd talk to them about what we were gonna do. I told her, "Neve, you cannot have a dressing room. They cannot even perceive that you have anything different from what they have. If you want to be a part of them, and you have to be a part of them, then I don't want you to come up and talk to me even." You know, she's the producer. I said, "You can call me at night if you want to talk about something, but I really don't particularly want to hear from you any more than I would any of the other dancers." And that's the way we played it.

She was pretty instrumental in getting the film made in the first place, right?

Yes. She started it. She was a dancer with the National Ballet School of Canada when she was a kid. And then she got into that movie star thing with "Party of Five" and "Scream." She said, "I want to do a ballet picture. I want to dance in a picture." And Warner Bros. spent, oh, I don't know how much trying to develop a script for her to dance in, but they were all the same script. You know, the little girl from the chorus gets her big chance, blah blah blah, and succeeds. She said, "I don't wanna do that. I just want to do a film that's truthful about dancing." So she got ahold of Barbara Turner, and they started writing this thing. They stayed with the Joffrey for three years, traveling and going in and out.

So a lot of what's in the film is based on real life?

Everything that Barbara had in her script when it was sent to me had occurred. Nothing was fabricated.

Were you worried about using dancers as actors?

Yes, at first I was very worried about whether the dancers could act or not, but they have all the elements except the voice. They spend their lives in front of the mirror, so they're not shy. They like themselves. They just don't have the practice or the philosophy of it.

Did you do anything special to deal with that?

Well, they never saw a script. I would just set up a scene and say, "Oh, by the way, why don't you talk to her about this, tell her that you hurt your ankle or your mother died or something, blah blah blah." And they'd just kind of take that and kind of go.

You're talking about improvising in rehearsal?

No, in shooting. It was improvised through all that. Because if I'd given them lines to learn, I think that they would have become bad actors. Those scenes with Deborah Dawn, the older dancer who said, "I can't dance that," for instance, were improvised, but she knew what she was going to say. So it wasn't like she was fumbling through. And all these things were truthful things about themselves or something that had happened to someone in the company. Like the girl who tore her Achilles'. That happened. She'll never dance again. And that's pretty much the way people remember it occurring, so we just restaged it.

You've talked in past interviews about valuing the truth over the facts. It sounds like this is a good example of you saying, all right, the script was very factual, but let's get to the truth of this world.

Yeah. The facts are the things that occurred. The door closed; that's a fact. It rained during the performance; that's a fact. But the truthfulness is the truthfulness of the characters themselves and how they really are with what they're doing.

Sort of boiling it down to its essence.

Right. But it's really fucked up my career.

Why?

Because it's hard for me. Now I read a script and I say, "Oh, god, these people are talking all the time. And they're telling you things. Why do we have to have that? And there's too much plot!" You know, I don't think this picture's gonna be huge at the box office. It's gonna be well-received and it's gonna be nice, but it's not gonna get any 14-year-old boys, unless they're gay. But it'll get a lot of 14-year-old girls.

Do you think about that when you're making a movie?

Sure. It would be irresponsible if I didn't. For me to go out and make a film and then sell it for the wrong reasons to the wrong people is just silly. So I don't imagine or envision an enormous audience for this. Unfortunately, in these times, films are done and they disappear. They're in the theater for how long? Two weeks? Three weeks? They're like popcorn; they're totally disposable. But a film like this should be able to be around for a couple of years. And it should be able to build an audience, a repeat audience, people who will say, "Oh, you gotta come and see this. It's really something."

Do you worry about your audiences? This film has a lot of your trademarks -- the big ensemble cast, the overlapping dialogue, the emphasis on character over plot. Do you feel like audiences are always up to the challenge?

No, but that's their problem, not mine. And the fact that you could even form a sentence that says that the films are not so interested in story. Well, who said there was going to be a story in the first place? You did, because that's the conventional wisdom that comes down to us. "Oh, it's a great story." Well, I could tell you the story about the guy [in "The Company"] who didn't have a place to sleep. You know his story. You know as much about him as I could tell you in the film. I don't have to end that. Or the guy who gets fired from the company, the guy who has the mentor, you could make his story up and be absolutely dead-on with it. I don't have to tell you any more about it. And I don't have to tell you about Harriet, the woman who we first see dancing, kind of working out, and when the other dancers, the real dancers, come in, she quits. Then she's in her mufti, her uniform, all day and -- you know her story, I don't have to tell you any more about that. The little love story is just sort of a concession to a film audience, because they come in, they've gotta see something.

Yes, the love story is so stylized. It's almost impressionistic.

I did that like a pas de deux. There is no conflict in that. Boy meets girl. Boy is attracted by girl. Boy fucks girl. Boy and girl fall in love. Boy and girl are becoming very happy. They each get injured and they laugh. But that's what a dance would be. And the same music is going on the whole time they're on, just like a pas de deux. That's the way a dance would be done. I wanted the whole thing to be just the mirrors that they're surrounded by in their milieu.

Do you think you have to be an established director to get a major picture made that hews so little to the Hollywood formula?

Well, in the first place, I don't work in Hollywood. This wasn't done in Hollywood. This money is all European money that I make my films on, and it's not very much. But that's just the way that is. And I frankly don't care. We're gonna show this picture tonight. It's gonna do well. We're gonna do really well with this picture, but it's never gonna make anybody any money. And it's never gonna win any big prizes. It simply can't because it's outside of the mainstream. It's closer to that wild goose film [the documentary "Winged Migration"] than it is to "Mystic River."

Let's talk about your notorious interview with the Times of London a while ago, when you said you were horrified by the Bush election and that after 9/11, when you saw the American flag flying everywhere, it felt like a joke to you. Do you still feel that way?

I spent all that time, the election -- the nonelection, etc. -- in London, so my sleeping time was totally reversed. Over there I have to be up until 5:30 in the morning to watch the news come through. And then I came back to New York after 9/11 to open "Gosford Park" and I got in a taxicab and the cab driver had on a turban that was made out of a flag. There were flags everywhere I looked. There were flags stenciled on the sidewalk. People were throwing up on them. And in one of these endless lines of one-liners that you go through at these premieres, I was asked, "How does it feel to be back in America?" And I said, "I think I'm gonna puke if I see another American flag." Well, Ollie North got hold of that and then I was harassed and really put in a position I'd never been in in my life. I'd never felt that kind of hate from people who don't know me and that I don't know. I just was stunned by it. If you question anything, you're a bad guy. And I just won't accept that. So fuck 'em all.

In that same interview, you said you thought Hollywood was somewhat to blame for 9/11, that movies gave the terrorists ideas and that "we should be ashamed of ourselves."

Oh, I didn't say that.

Well, they quoted you as saying it.

They may have quoted me that way, but I didn't say it.

OK. What about the story I read about you having invented a way to tattoo pets so that they could be identified and tracked to their owners. True or false?

True. After the war [Altman was a pilot in WW II], I had a dog and we developed this thing called "Identi-Code" so you could prevent vivisection. You could find your dog because inside of its groin, it had a number tattooed on it. It had a number of the state it was in, the county in that state, and then the dog's individual number. These records were all kept at the sheriff's department in each county. And I was the tattooer. I was the one who had to learn how to tattoo the numbers.

Wow. What happened to that business?

Eventually, we sold it to a dog-food company.

But sometime before that, you managed to tattoo President Truman's dog?

That was P.R. My dad knew Harry Truman. I'd played poker with Harry Truman. So I went to Washington and had a little influence with the secondary people. And Harry had this dog. He didn't care about this dog. It was just a family dog, so I tattooed it.

Shares