The Bush administration's invasion of Iraq has revived debates not heard since the end of the Cold War. America's leaders, and those Americans who support them, see the war on terror in general and the invasion of Iraq in particular as a necessary battle against evil, like the fight against Communism. Much of the rest of the world, and the American left, see Bush's crusade as simple-minded to the point of hysteria -- the same critique they leveled against Reagan-era anti-Communism.

In fact, neither side is right. These Cold War-era categories and battles are no longer relevant in addressing the issues posed by Islam, terrorism and the politics of the Middle East, and they obscure the real issues at stake. A further distraction are the passions, positive and negative, inspired by George W. Bush: Those who despise him are unable to accept that anything he does could be defensible, while his acolytes are equally myopic about the dangers and errors of his policies.

By insisting that the war on terror is a moral stand against evil, hawks elevate terrorism to a unique category that it doesn't deserve. They scare citizens into giving up freedoms -- undercutting America's credibility as the defender of freedom. They blur distinctions between different types of threats and risk demonizing Islam itself -- a dangerous development that is already sharply felt by people in the Middle East.

But leftists who rightly reject the vision of Islam as the enemy tend to dismiss its links to terrorism, underdevelopment and repression in the Middle East and outside it. And they are unable to understand how the invasion of Iraq -- despite the fact that it was sold under a false guise -- could and can move the region forward.

The Iraq invasion has a far more complex relation to the war on terror, and the battle to improve Arab and Muslim societies, than most partisans of either side are willing to admit. The invasion was justifiable, although extremely risky, because Iraq was a festering sore that was destabilizing the region and posed a definite threat to the West, though not an imminent one. The risk, of course, was that invading might result in unplanned consequences -- from mass anti-Americanism to Sunni rage, from the rise of Shiite fundamentalism to internecine strife, civil war and partition.

Many of those possible consequences are now threatening to become realities, thanks to the Bush administration's gross planning failures and bungling of the postwar period. The peculiarity of this historical moment is that the stakes are so high that if everything does in fact goes wrong, the invasion could turn out to have been a mistake. But it's too soon to tell.

Iraq under Saddam represented a major threat, but it is important to be clear about just what kind of threat. Saddam was a nasty dictator and a regional expansionist who might have launched more military campaigns against his neighbors if he had been allowed to. But it is becoming increasingly clear that he did not have any weapons of mass destruction, nor any ties to al-Qaida. He was a tin-pot dictator who did not pose a military threat to the West (in fact, the U.S. used him when it found it convenient to do so.) The real Iraq time bomb was not just Saddam's regime but the entire situation there, in particular the sanctions -- which were destructive and impoverishing, which generated Arab rage against the U.S. and could never have been ended without Saddam's departure.

It is commonly overlooked that during the entire decade of the Oslo peace process, the unresolved crisis in Iraq competed with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as the worst cause of tension between the Arab world and the West. On top of that, whereas the Palestinian leadership clearly made a choice to cooperate with the U.S., Saddam Hussein was a rallying point for defiance. Taken together, Iraq, sanctions, the presence of U.S. troops in Saudi Arabia (the issue that set off Osama bin Laden) and more general Western encroachment upon traditional Middle Eastern societies gave rise in the 1990s to a new, internationally active, violent movement that was quite separate from the earlier internationally active Palestinian movements.

The left, afraid of passing judgments on other cultures, has erred by not recognizing that there is something in the Arab world that has made it turn to international terror, when other regions facing similar problems have not done so. Removing Saddam's regime, and putting pressure on other states in the region to reform, could be a way of forcing the Arab world to face up to its shortcomings. But by blurring the distinction between Iraq and al-Qaida and using crude but politically useful fear tactics to create an Arab-Muslim terrorist bogeyman, the Bush administration has gone too far in the other direction. Partly because of these ideological blinders, partly because it is not as firmly committed to liberty and justice as it claims, either at home or in the crucial Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it has failed to take the necessary actions, both in post-invasion Iraq and in the region, to bring lasting positive changes to the region. And it has undercut America's ability to win the most crucial war of all: the war of ideas.

Instead of simultaneously fighting terrorism and concentrating on eliminating its root causes, Bush has only done the first. To whip up American support for his war on terror, he has played on Americans' fears, turning terrorism into an absolute moral evil and claiming that it poses as great a threat to the U.S. as the Cold War did. This is a mistake. First of all, terrorism strikes everybody, everywhere, not just the West and Westerners, even if they often seem to be the intended target. Second, terrorism simply doesn't pose the same threat as the nuclear standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union. Terrorism and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction in rogue states are urgent security threats, but they cannot be compared to the apocalypse the world faced during the Cold War. Terrorism, however painful and terrifying it is, is ultimately insignificant. It will not bring down any Western government; indeed, it is not even doing that in less stable parts of the world. It is a containable problem, just as it was in the days of the Cold War. We should not now promote it to something grander.

The war on terror does indeed reflect a confrontation between the West and the Arab or Muslim world, but it bears no resemblance to the Cold War. There is no common enemy on the Muslim side, no Arab Warsaw Pact. There is no monolithic front against the West or anybody else, as indeed there is no unified attitude on this in the West. Nor is there a real ideological contest. Islam, despite its sometimes expansionist agenda (which it shares with many other religions), is no ideological rival to the Western way of life. It is true that many in the Arab and Muslim world fear being overwhelmed by Westernization, but many other regions share this concern, and have just as many other points of contention with the West.

Moreover, the international terrorist campaign the world is witnessing today is not particularly new. In the 1970s, an alliance of largely left-wing movements around the world, partly inspired and backed by the Soviets, also formed a huge network of interrelated terrorist cells. The international terrorist Carlos was the bogeyman then. Today's Afghanistan is yesteryear's Lebanon.

The idea that the current wave of terrorism is radically different from earlier forms, apocalyptic rather than political, is also misguided. Osama bin Laden's al-Qaida and similar groups have very clear political goals, even if they have a religious background or justification -- and many people in the Middle East share those goals. The perpetrators of the attacks and their backers have very similar aims to some of the terrorists who operated in the 1970s. What indeed is the difference between groups such as Germany's Red Army Faction and al-Qaida? Is there a real difference in the Communist fight against capitalism and the fundamentalist fight against Western cultural and political dominance? And is al-Qaida's attempt to drive the U.S. out of the Middle East so different from the actions of smaller nationalist movements, such as the Irish Republican Army and the Basque ETA, who are trying to drive respectively Britain and Spain out of regions they claim?

Had it not been for the 9/11 attacks, it is doubtful al-Qaida and other fundamentalist groups would have been assigned a new category of terrorism all to themselves. And despite the horrific scale of those attacks, it was neither wise or constructive to do so. Elevating Islamist terror to a special category has had disastrous consequences both within America and abroad. Domestically, it has led to loss of liberty; internationally, it deepened the suspicions of Muslims and Arabs that the U.S. had no intention of dealing fairly with them.

Nor has it had a positive effect on our battle against terrorism. Years of experience have taught the West that the best way to fight terrorism is by using a law-and-order approach. Terrorists are criminals, to be hunted down and apprehended. (Afghanistan was a special case, a state whose ruling Taliban regime was virtually indistinguishable from an international terrorist organization. Invading Iraq was justifiable but not because of terrorism.) The very phrase "war on terror" is therefore dangerous, because it exaggerates and mischaracterizes the threat.

A clear-eyed look at the conflict shows that the Bush team is not winning this war -- but it hasn't lost it yet, either. The American efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq are floundering, despite the capture of Saddam, but the Iraq invasion has not led to the huge increase in attacks around the globe that some had feared. Indeed, if you exclude the "hot zones" -- Israel and the Palestinian territories, Iraq and Afghanistan -- the number of terror attacks has been about the same in 2003 as the year before. (Actually, because of the Bali bombing, the death toll in 2002 was even higher than that in 2003.) Nor has the invasion convulsed the region, as many feared: The Arab regimes are still as firmly or shakily in charge as before. On the other hand, the positive developments that the war's architects claimed would follow the invasion have not taken place: Democracy and freedom have not spread throughout the Middle East, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict remains unsolved.

The most ominous fallout of Bush's war on terror has been the dramatic rise of anti-American and anti-Israel sentiments around the world. There is a widespread feeling that both countries are overreacting to terrorist attacks that don't threaten their existence -- abusing genuine security concerns to further an expansionist political agenda. If resentment is a reliable indicator of the possibility of future terrorist attacks, then the prospects are grim. And America's errors in dealing with postwar Afghanistan and Iraq and its failure to use its power to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are compounding this resentment.

Not terrorism itself, but the way states react to it, will ultimately determine who wins the war on terror. Not one Western democracy has ever been fatally destabilized by terrorism. Even in the (flawed) democracy most plagued by terrorist attacks, Israel, the state, society and even the economy have continued to function moderately well. On the contrary, it is the Palestinians whose governing institutions, society and economy have been devastated in this battle.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict offers an interesting object lesson on the purpose and impact of terror campaigns. Insofar as it has a political objective, the goal of Palestinian terrorism since the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993 has been to disrupt the peace process, not to advance it. (Although some Palestinian terror attacks, as the Israeli journalist Amira Hass has noted, are simply acts of revenge or despair.) The violence has been partly successful in achieving this goal because the extremists knew that they had a partner on the Israeli right, which was also working to torpedo the peace moves. If the Sharon administration, rather than clinging to the occupied territories and the settlements, had actually pursued murdered Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin's famous injunction to "negotiate as if there was no terror and deal with terror as if there were no negotiations," Palestinian terrorism would be challenged and eventually eclipsed by a political solution.

In other, less-stable or non-democratic countries, both the goals and the impact of terrorism can be different. In the Middle East the clearest example of this is Egypt. In the 1980s the fundamentalist group Gamaa Al-Islamiya waged a violent campaign against the government. Along with other fundamentalists, its members assassinated the country's president, Anwar Sadat, for making peace with Israel. The peace treaty has survived, as has the Egyptian government in a largely unchanged form. The Islamists were suppressed partly through a ruthless and violent campaign against them.

But the other element in the government's campaign to neutralize the fundamentalists was to adopt their agenda. The peace with Israel has remained cold largely because of this. But domestic policy changes were even more significant.

Freedoms across the board came under fire. The government cracked down not only on fundamentalists but on all forms of dissent, including political movements, human rights organizations and intellectuals. Anxious to woo the Egyptian public -- composed mainly of moderate yet deeply conservative Muslims -- Mubarak's regime took steps against a wide variety of groups and phenomena, including homosexuals, the Coptic Christian minority, belly dancers, sexual innuendo on television and "lewd" or religiously charged publications. The result has been that jailed leaders of the Gamaa felt simultaneously threatened and comfortable enough to declare last year that they had made a mistake in launching the campaign of violence. The government had vanquished terrorism, but at what price? It can as easily be argued that the terrorists had achieved at least part of their objective.

Despite the dispiriting results of these two very different terrorist campaigns, they have not completely succeeded. Egypt's government is still firmly in charge and the country has not turned into the puritanical Islamic state that the fundamentalists seek. In Israel, the attacks and Prime Minister Ariel Sharon's failure to pursue a political solution have succeeded in derailing the peace process, but the militants' longer-term goal of regaining the whole of Palestine remains a pipe dream.

In this regard, how Turkey responds to November's terrorist attacks in Istanbul is a key indicator of whether or not the war on terror is being won. The first twin attacks on the synagogues in the center of town hardly caused as much as a traffic jam in this huge and bustling metropolis. Life went on, and the occasion provided a marvelous opportunity for the moderate Muslim party in power to demonstrate its tolerance and concern for minorities. On a geo-strategic level, the same firm yet concerned tone was in evidence in a pledge to maintain friendly ties with Israel. If Turkey stands fast and refuses to make concessions to the radicals, that would demonstrate the nation's increasing stability and confidence -- and would be a far greater success in the war against terror than capturing Saddam or any displays of high-tech military wizardry.

Unfortunately, the self-appointed leader in the war on terror, the United States, has already lost a crucial battle in that war. By cutting back on civil liberties, the Bush administration has shown weakness to America's enemies and weakened its own standing as an exemplar of freedom.

Bush's compromising of civil liberties has been spearheaded by his attorney general, John Ashcroft. Allow the writer one personal anecdote at this point. While covering the congressional midterm elections in 1998 in Dick Gephardt's St. Louis district, I came across then-Sen. Ashcroft at a Republican fundraiser. Upon hearing that I was from Europe he proceeded to question me about a variety of issues such as healthcare and social benefits. After every answer, he almost immediately interjected something along the lines of, "But isn't it much better here?" It does not seem very surprising that he grew into the promulgator of the USA PATRIOT Act. My experience of U.S. senators is limited, but it seems to me that the United States needs leaders who are not quite so unfamiliar with the rest of the world and not quite so smug.

By taking such extraordinary measures in the face of Islamic fundamentalist terror, the authorities in the West give it a status that was not even achieved by Communist networks during the Cold War. By changing its internal posture the U.S. sends a signal of weakness, one that people in the Middle East, attuned to such measures by the actions of their own repressive governments, are especially sensitive to.

But even worse, the U.S. is giving up on the war of ideas that this confrontation is really about (and that the administration invokes for propaganda purposes). When President Bush talks about bringing democracy to the Middle East, he addresses the core issue of the West's relations with the Arab world. But how can he talk about bringing civil liberties to the Middle East while limiting them at home, and failing to deal evenhandedly with the Israeli-Palestinian issue -- which more than any other issue shapes Arab attitudes toward the U.S.? This points to a central paradox that plagues this administration's high-minded war on terror: It is fighting that war on premises that it itself does not fully believe in or act on.

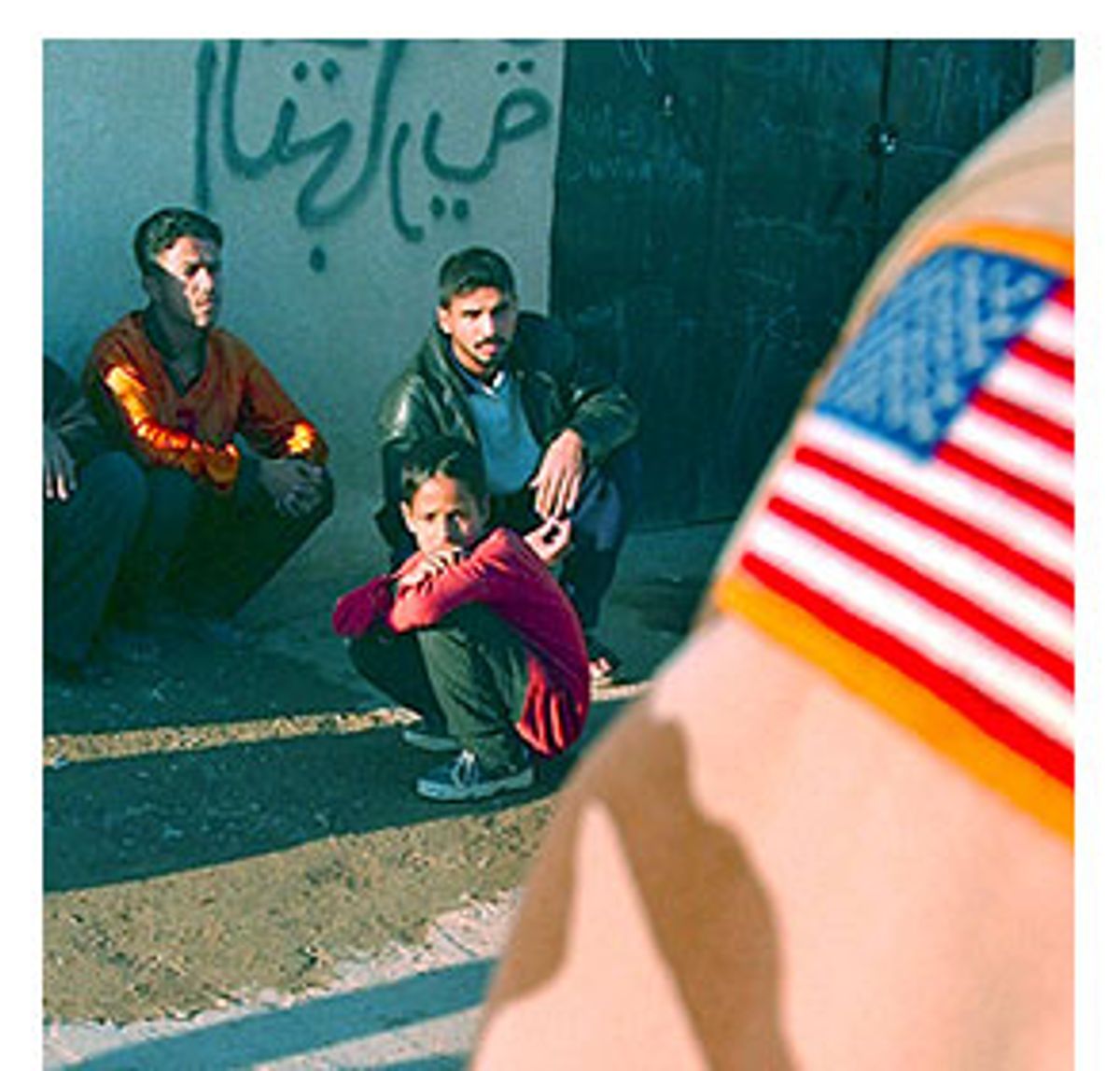

The invasion of Iraq is a case in point, to the horror of people who have witnessed it firsthand. What should have been a celebration of democracy became a ham-fisted occupation. It's true that the population brought much of its woe upon itself with unrestrained acts of pillage and looting. But nothing can excuse the terribly botched postwar planning (which allowed that looting to take place) and the near-total lack of any injection of enthusiasm about democracy. The first thing that America should have done, after restoring basic services (much more rapidly than it did) or even during that process, was to organize festive local gatherings throughout the country to elect temporary representatives of the people, even if that process was bound to be flawed. It is understandable that the U.S., having won the war, wanted to safeguard its interests, but it should have set a timetable from the very beginning for handing over civil responsibility to an elected Iraqi government. The high-handed way in which the occupation was handled did not spell democracy to the people of Iraq, nor to potential European allies -- whom Bush had already alienated in the run-up to the invasion.

The problem is that in the Bush administration, the U.S. does not have the great defender of liberal values that the West needs at this crucial point in history. An ideologically extreme group that is mean-spirited about a whole range of liberal, civil-liberties and personal-choice issues, from abortion to the environment, from tax-breaks for the rich and crony capitalism to gnawing away at benefits for the poor, does not a good defender of the West make.

It is true that many on the left, especially the European left, have for too long failed to stand up for the ideas that have formed Western society since the Enlightenment. Even today many European leftists are somewhat shamefaced about openly defending the values that make possible the kind of open society that has become a beacon for so many others around the world. Even when confronted with militant Islam, which makes no bones about its values and is willing to promote them through violence, some in the West hesitate to clearly declare their allegiance to liberal values, as if to do so would be to engage in cultural colonialism or to echo the racist, imperialist rhetoric of "the white man's burden."

Toppling Saddam was a worthy deed, and much good could still come from the U.S. presence there. But this administration is particularly ill-suited to convince the rest of the world and the Iraqis themselves of its good intentions. The Bush team is fighting this war of ideas almost exclusively with military tools and displays of power politics, both abroad and at home.

Force has its place. A violent threat, such as terrorism, sometimes has to be combated by a well-chosen military action, as in Afghanistan. Vested interests in the Arab and Muslim world and elsewhere may resist the opening up of their societies, and it may be legitimate to counter them when their stagnation and repression threatens others. But in the end, it is essential for the West and the U.S. to convince most of the people who find themselves fearing Westernization and globalization that they can take the best of the West and still retain their own cultures and identities. And it is essential that the West practice what it preaches -- in Baghdad, in New York, in Nablus. That is the arena in which the real war, the war of ideas, is taking place -- and it is a war that America, under George Bush, is losing.

Shares