"I've seen the way you behave with women. In that respect you are totally unreliable, but we could have an interesting life together."

-- Pauline Potter, proposing to her future husband, Baron Philippe de Rothschild

My girlfriend Natalie is not classically pretty, but that's never been a problem. She has a little belly, but she flaunts it. She has a little bit of extra butt. She flaunts that too. She's had her share of romantic encounters, but she's still single, over 35, and has lots of baggage, including a 5-year-old from a previous marriage who's earned the nickname of Rasputin. In many respects Natalie is the perfect candidate for Rachel Greenwald's new book "Find a Husband After 35 Using What I Learned at Harvard Business School." She's perfect except for one thing: Natalie is French.

"I feel sorry for American women," she says over the phone. Natalie is in Paris; I'm in Los Angeles. We're talking on the phone about love, lust, girlhood, womanhood. Somehow we touch on Greenwald's new book, which exhorts women to use the same marketing techniques to find a mate as they would to, say, launch a new brand of tennis shoes. "You, the reader, are the 'product,'" Greenwald writes.

I hear Natalie sigh over 6,000 miles of fiber optic cable. "Only in America could you get away with this type of lunacy. There is so much pressure on American women to be happy. To sweep away all traces of loneliness, to forget who you are in your search for a lover or a spouse. In France young girls learn that happiness is elusive; we learn that happiness is less important than passion."

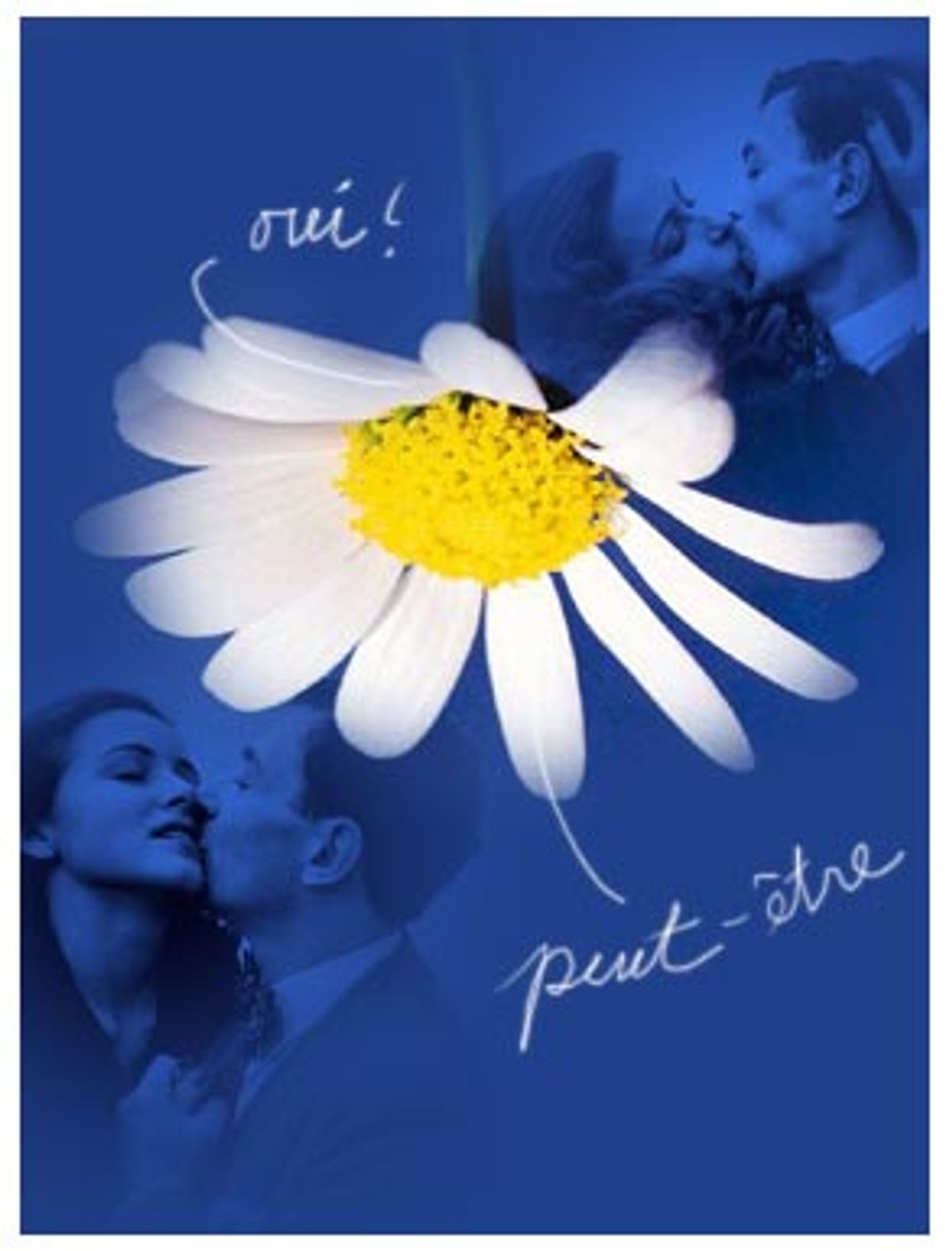

Natalie's comments remind me of a salient little metaphor: As girls we Americans sit in our field of daisies and pull off petals with, "He loves me, he loves me not, he loves me, he loves me not." Meanwhile French girls sit in their meadows with their marguerites and pull off petals with: "He loves me a little. A lot. Passionately. Madly. Not at all." Why does the little French girl innately think in nuances and increasing levels of passion while we're mired in the black-and-white of total love or utter rejection?

According to Christophe, a French journalist with a seriously lush history of romance on both sides of the Atlantic: "Everything in your culture is defined like a contract, even the business of love. That's precisely the opposite in France. I've dated French women for months before I ever really knew who they were or what they wanted from me. After the first or second date, the American woman wants everything spelled out: 'Are we dating? Are you my boyfriend or just a friend?' A French woman doesn't do that. She doesn't give much away. She's comfortable letting things evolve naturally, but the ball's almost always in her court."

Natalie concurs with this assessment. "There is a culture in France of the 'non-dit,' the not-spoken. What you don't say in France is as important as what is said. There are boundaries in language that create tensions. Even sexual tensions. The simple act of saying "tu" or "vous" is a boundary that invites intimacy or precludes it. We learn that we have more power when we keep things to ourselves than when we give things away. We learn that the art of seduction is based on innuendo and silences."

Innuendo and silences? This sort of quiet, coded game of love is entirely baffling to us buffoonishly direct Anglos, and it's partly what's kept French women in the sexiness hall of fame for centuries. Never mind haute couture or racy lingerie. French women are a bundle of alluring contradictions that seem to perfectly coexist, like the unlikely mélange of sweet and sour. They're often annoyingly coy and darkly wanton. Many of them are not great beauties and yet are gorgeously compelling in the way they reconcile their imperfections. They tend to be more concerned with experiencing pleasure than with being liked and far more passionate about having a life than making a living. (Multitasking does not rank high on their list of positive attributes in a woman.) Plus they all seem able to walk gracefully in high heels on cobblestones the size of grapefruits. Talk about poise.

This amalgam of qualities has given French femmes a singular sophistication that makes the dictates of Rachel Greenwald seem almost bizarrely childlike. In her classic "The French and Their Ways," Edith Wharton had already singled out this sophistication back in 1919. The French woman "is in nearly all respects, as different as possible from the average American woman," Wharton wrote. "Is it because she dresses better, or knows more about cooking, or is more 'coquettish,' or more 'feminine,' or more emotional, or more 'immoral'? The real reason is not nearly as flattering to our national vanity. It is simply that the French woman is more grown-up. [Wharton's italics.] Compared with the women of France the average American woman is still in kindergarten."

Excusez-moi: Did you say kindergarten? I suppose if Wharton were comparing French and American women over the long course of history, then we Americans would be the innocent toddlers. When I was a girl I used to marvel at French women in history books precisely for this reason. They led armies of querulous men. They were burned at stakes. They got their heads chopped off for being petulant little queens. They were sexy and bellicose and bare-breasted. Even the symbol of the French Republic, the fair-haired Marianne, stormed Paris with (if we take Delacroix's depiction of her as our reference) her impudent and perfectly pulpy breasts exposed. French girls grow up with this legacy of women who were utterly feminine and totally kick-ass; a legacy of bare breasts, revolutions, royal courts, sex, death, blood, guts and great hair. Meanwhile, my generation of American girls grew up with Betty Crocker, Girl Scouts and training bras -- and Julia Child was as French as it got. How unfair is that?

Perhaps American women are ahead of the French when it comes to liberation. "You Americans were grown-up feminists," Natalie says when I bring up Wharton's comments. "We took all of our cues from you. We were incredibly old-fashioned and repressed compared to American women when it came to feminism. But we never confused the power of feminism with the power of femininity, the power of the femme. Being a grown-up to a French woman means being complete, with or without a man, but still being in love with love."

Christophe looks at the question differently. "We're a grown-up culture. America is a super power but historically you're barely adolescent. We were dismissing the Church because of its corruption hundreds of years ago while you Anglos were naively embracing it. History has taught us that you can't rely on dogma or doctrine. Relationships burn brightly, then die. We have our passions, our human tragedies, our loves and our losses. We have a couple of centuries of living and dying over you Americans."

I suppose you have to call a historical spade a spade. We Americans are big, hormonally super-charged 13-year-olds raiding the fridge in quick-fix binges. The French are wizened denizens sipping Bordeaux and plumbing the depths of passion and pathos. To their credit the French, who can be exasperatingly pig-headed and irascible, do have a certain ripened maturity and an insatiable appetite for the harsh realities and curious lusts that characterize matters of the heart. This is partly why the myths of the French mistress and the Latin lover have endured over the centuries. It might also explain why the French are so iconoclastic, even quixotic, in their interpretations of love.

I'm reminded of this sexy, baffling quality about the French time and time again. Most recently, it was while watching the Claire Denis film "Friday Night": Two strangers meet in a car in a traffic jam. They spend nearly the entire film in silence, end up in a hotel, make love rhapsodically, exchange a few words (barely) over pizza, make love again, then say goodbye. What just happened? Our leading lady -- who's not a great beauty but still lovely in an ordinary, je ne sais quoi way -- runs through the streets of Paris at night after her affair. All we know about her is that she's going to move in with her boyfriend. She's just left her mysterious lover in the hotel. Who is he? Will she see him again? Was it a one-night stand or the beginning of a long-term relationship? Our heroine runs down the street toward an unknown future, a liberating and strangely happy glow on her face. She doesn't seem to care. Clearly, Rachel Greenwald would not approve.

Shares