Bill Ellis goes to some lengths to convince you that he's a normal American. The biographical blurb in the back of his new book, "Lucifer Ascending: The Occult in Folklore and Popular Culture," assures readers that he's an "active member of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America" -- perhaps the most mainstream and least controversial religious affiliation one can imagine.

When I first contacted Ellis about an interview, he replied by e-mail that a reporter from another publication had recently insisted on visiting him at home in Hazleton, Pa., to watch him celebrate Halloween and then attend church the following Sunday. "I'm not sure what he expected," Ellis wrote, "but we did not sacrifice any goats on the former date and didn't have anyone slain in the spirit or exorcised of demons on the latter."

Indeed, when I finally reach Ellis by telephone one recent morning, he does not come off like the goat-sacrificing, demon-exorcising type. He's a soft-spoken man with a mild demeanor, careful to avoid overstatements and generalizations, and his sense of humor is so dry as to be almost imperceptible. He has to take a moment near the beginning of our conversation to help his arthritic dog in the door and up the steps to her food bowl. At one point, he describes himself as a "solitary," a word used by Wiccans to denote a person who is interested in witchcraft but belongs to no coven. There is no folklore department at the Hazleton branch campus of Penn State, where Ellis teaches English, and almost all his contact with colleagues is via the Internet.

Yet one could make a case that this unglamorous professor is a curious kind of cultural hero. At the very least, Ellis has demonstrated courage and fortitude for little tangible reward. His research field -- Satanism and the occult, especially as perpetuated in the folklore and rituals of teenage culture -- is not seen as respectable either by the society at large or the academic world. He has sporadically been attacked by fundamentalist Christians for spreading the evil gospel of the Horned One. "If you think that Satan is not alive and an ever present threat to Christians," wrote one Penn State alumnus, "then you are either (A) not a Christian or (B) a dupe of Satan himself." The writer went on to say he would pray for Ellis' removal from the classroom -- a prayer the university administration, to its credit, has declined to answer.

When I ask whether people in Hazleton judge him harshly because of his scholarly interest in Satan, Ellis chuckles quietly. "I would say they would judge me harshly on my commitment to literacy," he says. "We're in an area where intellectualism is not especially liked."

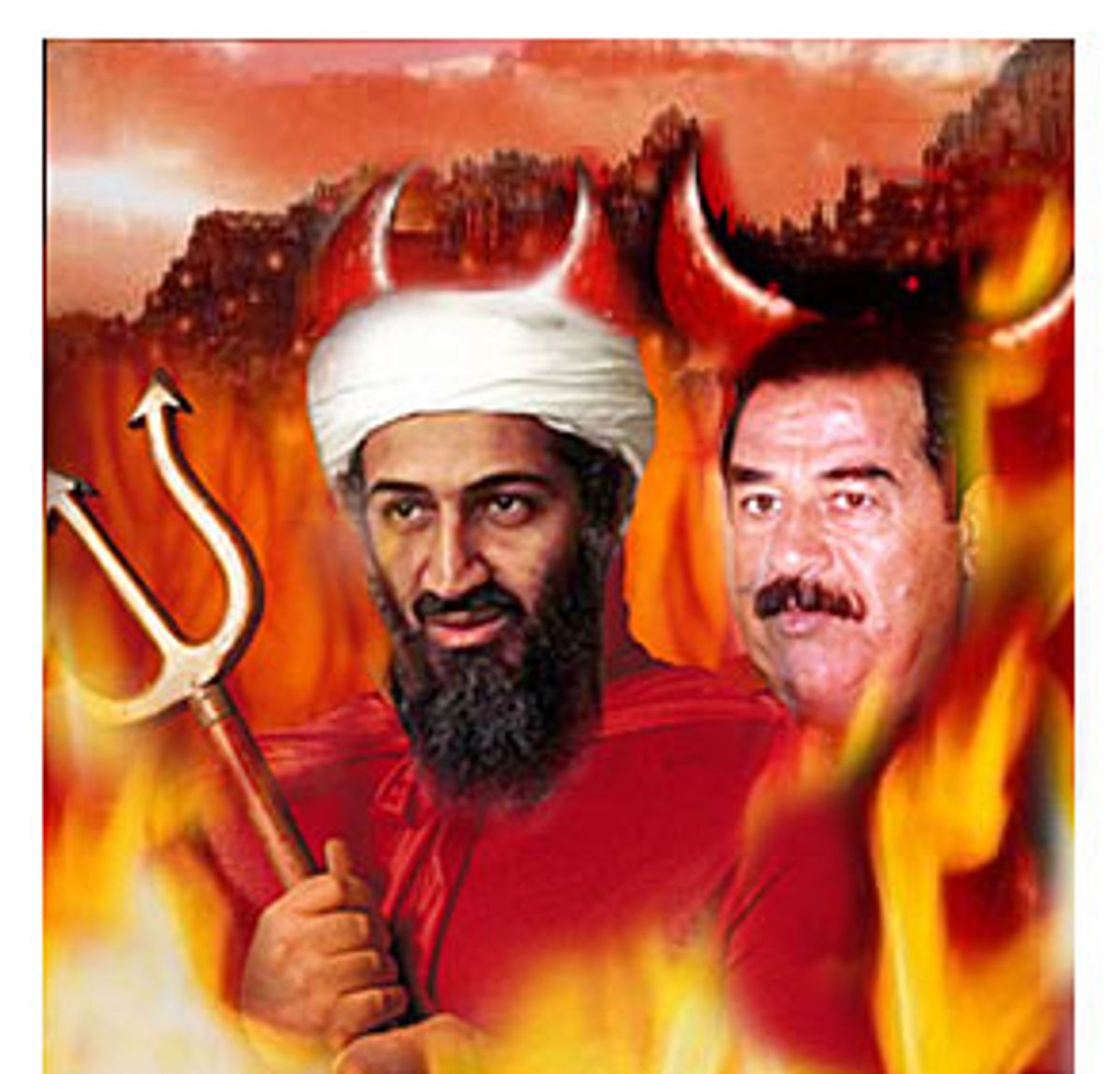

But the more you read about Ellis' research into the history of Ouija boards, chain letters, lucky rabbit's feet and adolescent "legend-tripping" (i.e., late-night visits to haunted graveyards and other spooky locations), the more you understand that behind these obscurities lie key questions in contemporary culture. Among other things, Ellis says he understands exactly why so many Americans believe that Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden were working together, despite the lack of any factual evidence to support that claim.

In both "Lucifer Ascending" and his 2000 book "Raising the Devil: Satanism, New Religions, and the Media," Ellis builds a sober and persuasive argument that the recent hysteria over the influence of Satan in America, much of it emanating from the Christian right, reflects a misunderstanding of a cyclical or dialectical process that has repeated itself for centuries. The dorm-room séance and the midnight cemetery voyage in some dude's unmuffled Camaro, he argues, are debased fragments of an ancient and genuine folk-witchcraft tradition. (More so, perhaps, than the New Age feminist happy-talk of contemporary Wiccans and neo-pagans, although Ellis speaks respectfully of such boutique beliefs.) As such, they reflect an eternal struggle between individuals and institutions over access to spiritual and supernatural realms, and the equally eternal struggle of teenagers to resist adult authority in general and the strictures of organized religion in particular.

Most significantly, Ellis argues that occultism and evangelical Christianity are more closely related than the devotees of either are likely to admit. The two phenomena have shaped each other, with the Spiritualism craze of the 19th century (which produced the Ouija board, among other phenomena) leading to the explosion of Pentecostalism, with its emphasis on individual experience with demonic possession and the Holy Spirit, early in the 20th. Today, after an interlude in the middle of the last century when American Christianity was dominated by mainstream Protestant and Catholic theologies -- religion based on "intellectual ethics," in Ellis' words -- the charismatic, holy-roller, born-again faiths are back with a vengeance. And so is Satan.

For many evangelical Christians, Ellis explains, the Man-Goat and his legions of demons are not metaphorical or intellectual constructs. "The trend in Christianity toward Pentecostal, charismatic modes of worship really has revived the experience of Satan, rather than the concept of Satan," he says.

As difficult as this can be for atheists, agnostics and even mainstream religious types to accept, Ellis insists that the ecstatic transformations seen at a Pentecostal revival -- speaking in tongues, being slain in the spirit, the exorcism of demons, etc. -- reflect something genuine and powerful. (No one who has ever witnessed such a service, regardless of his or her personal beliefs, is likely to doubt this.) Whether you believe the experience is spirit possession or a dissociated psychological state is, of course, an irreducible question of faith. But all religions that rely on such incandescent moments -- from snake-handling Pentecostalism to Christian Science to Wicca to the animist faiths of sub-Saharan Africa -- must confront what it means when the spiritual experience turns sour.

"Any religious movement that involves being born again, some kind of ecstatic experience, is quite aware that you can have good trips and bad trips," says Ellis. "When you dissociate your personality and allow someone else to step in, so to speak, most of the time it's going to be somebody good. It's going to be the Holy Spirit, it's going to be your spiritual helper, whatever term you wish to use. And then, a certain number of times, it's going to be somebody bad.

"Satan is the cultural name that has been given to those experiences for several millennia" within the Judeo-Christian tradition, he goes on. So believers who have witnessed ritual spirit possession in their churches, both positive and negative, "don't have to be convinced to believe in the devil. They've felt the devil. They've experienced the devil."

In other words, the explosion of fundamentalist Christianity in the United States in recent years has led directly, even inevitably, to widespread public belief in the Father of Lies and his nefarious schemes -- a topic avoided by mainstream religion for most of the 20th century. Not so paradoxically, it has also led countless heavy-metal musicians and their fans to embrace the trappings of Satanism, on the time-honored premise that anything that outrages and horrifies adult authority figures is inherently cool.

Nothing exemplifies this dialectic better than the infamous Onion article published in 2000 titled "Harry Potter Books Spark Rise in Satanism Among Children." To regular Onion readers, this article, with its ludicrous factoids about millions of J.K. Rowling readers fleeing from Sunday school to Satanic churches, forming their own schoolyard covens (membership fee: $6.66!) and proclaiming that "Jesus died because He was weak and stupid," was an obvious and even rather heavy-handed spoof. (Its outrageous coup de grace was a spurious quote from Rowling, crowing that "the weak, idiotic Son of God is a living hoax" who will be forced to "suck the greasy cock of the Dark Lord" on the Day of Judgment.)

But as Ellis discusses in "Lucifer Ascending," fundamentalists took the story at face value, and it spread through Christian anti-occult circles like an unstoppable virus. A chain letter containing the text of the Onion piece was forwarded from one believer to another (usually with the obscene quotation redacted), along with appended messages urging recipients to "forward to every pastor, teacher and parent you know ... Pray also for the Holy Spirit to work in the young minds of those who are reading this garbage that they may be delivered from its harm."

What Ellis may not have noticed is that even now, more than three years after the hoax article was first spread (and then widely debunked), and despite Rowling's frequent avowals that she herself is a believing Christian, fundamentalists on the Internet have not quite abandoned the cause. At the evangelical Web site Greater Things, pseudo-damning quotations from Rowling are assembled ("Death and bereavement and what death means, I would say, is one of the central themes in all seven books"), and the site's author explains that the Onion article itself was yet another diabolical machination: "One of the tactics of Satan is to make fun of those who cry 'evil' or 'foul,' by creating parody designed to make the concerned Christian look foolish."

Sincere believers, the site continues, "intuitively sense (by the Spirit) that there is cause for concern about these books" and so became vulnerable to the Onion hoax. By the same token, Ellis argues, you can't understand contemporary American politics without understanding the importance of profound spiritual faith, and specifically belief in Absolute Evil. "An experience-centered believer," he says, "is going to think and vote different ways from someone who -- like me, being a Lutheran -- checks the precedents and reads the Bible and thinks for a while before making a decision."

So when our born-again president refers to Osama bin Laden as "the Evil One," he is not dealing in metaphor or analogy, even assuming he is capable of such things. Rather he is addressing his co-religionists in a not-so-secret code. "That makes perfect sense to a born-again believer," Ellis says. "Evil, like God, is One. So you can say, and believe in, an 'Axis of Evil,' because you know that the person who is giving the orders to bin Laden and Saddam Hussein and the leader of Iran and the leader of North Korea is, of course, Satan."

Ellis also believes that the current belief in Satanic evil (and the Saddam-Osama linkage) is connected to 20th-century right-wing fantasies about the Illuminati, a Jewish-run conspiracy that aimed at taking over the world, often through the United Nations, an international banking consortium or some other nightmarish force. "You did not have to believe that the members of the Illuminati all belonged to the same ideology or ethnic group," he says. "Some would be communists, some would be alleged liberals, some would be terrorists. But they would all be working together in the same diabolically inspired plan."

As a scholar and historian, Ellis is inclined to believe that religious manias, both of the Christian and occult varieties, inevitably burn themselves out. Organized religion and the folk-witchcraft traditions, he suggests, balance each other out in the long term in what he calls a "Luciferian dialectic." But as the witch trials of medieval Europe and colonial Massachusetts, the Red Scare of the 1950s and the Satan panic of the 1980s also indicate, these moments of ecstatic belief can also produce fervent persecutions of dissidents, heretics and perceived enemies of all kinds.

Ellis explains this in neutral, anthropological language, but its relevance to George W. Bush and John Ashcroft's America -- where the Constitution seems increasingly endangered and prominent Christian ministers accuse Muslims of worshipping the Moon God -- should be obvious. "One group can become so convinced of its religious rectitude, and so convinced of the danger that the Other puts them into," he says, "that they end up taking political and legal action against the Other. And of course, the fact that they're doing this for God makes them even less critical than they otherwise might be about the evidence and about their own motives. This is why I'm writing these books -- I'm trying to get people to see these dangers."

Shares