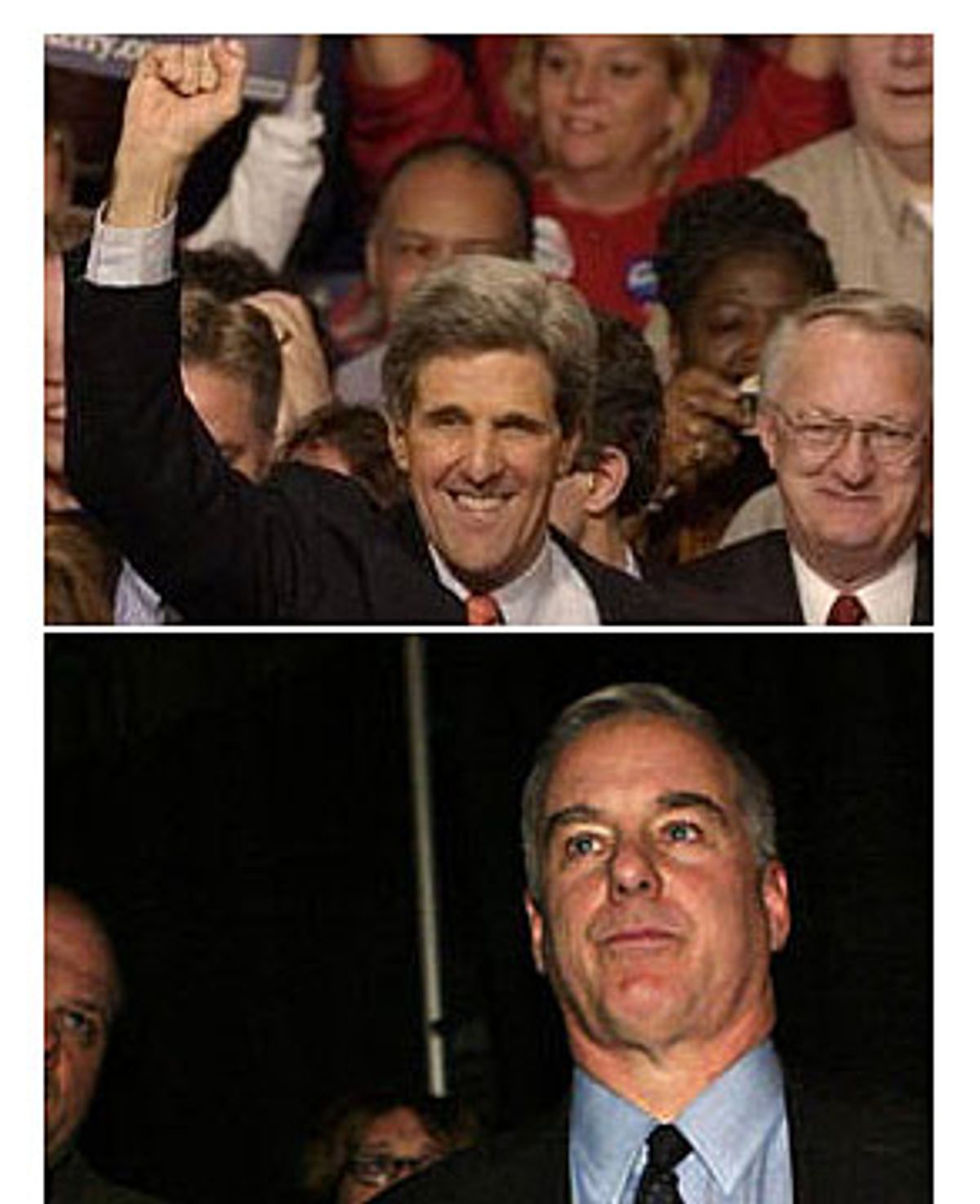

Even before the Iowa caucuses had closed, John Kerry's headquarters was consumed by celebration and Howard Dean was on television explaining why his stunning loss wasn't really a loss at all.

The results were surely beyond even their most extreme expectations. The Massachusetts senator, whose campaign seemed to be on death's door just a couple of weeks ago, claimed 38 percent of Iowa's caucus-goers. Dean, for weeks seen as the front-runner here and nationally, finished with less than half that total -- 18 percent. The night's other big winner was North Carolina Sen. John Edwards, who, like Kerry, came on strong at the end of the race to finish with 32 percent.

"Thank you, Iowa, for making me the comeback Kerry," the winner said to jubilant supporters in a ballroom of the Hotel Fort Des Moines. "Not so long ago, this campaign was written off ... You listened. You stood the ground. And you stood with me on caucus night so that we can take on George Bush and the special interests and give America back its future and its soul."

The Iowa caucuses are traditionally the formal kickoff to primary election season, but as with New Hampshire, where voters go to the polls for a vote next Tuesday, it's easy to overstate its importance. Clearly, though, the outcome last night reordered the Democratic contest for the nomination that will end in Boston in July. Kerry's back in. Edwards is back in. Dick Gephardt, the Missourian expected to make a strong showing next door in Iowa, placed a distant fourth with 11 percent and quit the race. And while Dennis Kucinich might stay in, he barely registered in the final tally.

"I think it will be easier if the race is as close as it appears for pundits to identify losers rather than winners tonight," Iowa Gov. Tom Vilsack, a Democrat, said in an online discussion today on WashingtonPost.com. "A candidate who finishes a distant third or fourth may have difficulties in future primaries or caucuses."

Indeed, it was arguably Dean who suffered the most significant setback. Just a few weeks ago, pundits predicted that he would clean up here and in New Hampshire, and use that early surge to overwhelm all opposition. Even though he's leading in New Hampshire polls, that scenario is shot. Not only will he be up against Kerry's momentum next week, but he'll also face retired Gen. Wesley Clark, a Democrat who skipped the Iowa contest and who has made a strong showing in recent New Hampshire polls.

Tonight's results are going to be imbued with all sorts of meaning over the next week that they may not deserve: Just as the consensus drumbeat for the last several months was that the contests will be Dean's to lose, his rejection by Iowa voters will doubtless be overinterpreted as a sign that he can't win anywhere. He told supporters last night that he would press his campaign in every state of the nation -- and, perhaps more than any other candidate, he has the money and the organization to do so.

But Dean's money and organization only went so far in Iowa. His campaign invested heavily here, and he seemed to be headed for the sort of strong showing that would have allowed him to dismiss opponents' and the media's criticism of his campaign as the rantings of political insiders who are biased against him.

On Monday night, Dean was left to put the best face on disappointing results. "If you would have told me a year ago that I was going to finish third in Iowa," he said on CNN, "I would have been delighted."

But the margins of Dean's defeat provide some crucial insights: It debunked the notion that he's inevitable, and that attacks somehow only make him stronger. His early popularity here was clearly diminished by his opponents' attacks on him on the air and on the stump, and by some of his comments that the press called "gaffes," but which Dean defended as mere honesty. More important is that, during a week's worth of conversations, Iowans with surprising regularity described Dean as arrogant, and it's clear that his style played a significant role in driving support to Kerry and Edwards.

At best, Iowa will serve as a warning to Dean about his stylistic shortcomings; at worst, it will leave him fundamentally weaker for the contests to come. A week after New Hampshire, there are contests in seven states: Arizona, Delaware, Missouri, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma and South Carolina. While Clark and Edwards, both Southerners, have looked forward to that day, none of those states seem like advantageous ground for Dean.

For Kerry, the result could provide a critical boost going into New Hampshire. But it's no sure bet: He still trails Dean and Clark. Back in November, Kerry dramatically overhauled his operation, changing his campaign manager and essentially pulling out of New Hampshire in order to concentrate his efforts on the contest in Iowa. In recent weeks, he has taken a more hands-off approach to the tactical decision-making of the campaign, focusing almost exclusively on his personal appeals to Iowa voters.

It is also important to take notice of the strengths of Kerry and Edwards as candidates. Their showings defied the indisputable superiority of the Dean and Gephardt organizations in Iowa, and were largely attributable to their exhaustive personal appeals to Iowans, in which they won over supporters rally by rally and town by town. And it also showed that appeals based on "electability" can work among the sort of active Democrats who participate in the Iowa caucuses, and who seemed united by a desire to defeat President George W. Bush in November.

A number of factors changed the dynamic late in the race. Dean got some tough coverage in the press, including a story that was widely reported in Iowa about comments he'd made four years ago that were critical of the Iowa caucuses. Dean's popularity may also have suffered, along with Gephardt's, because of a mutually destructive negative ad campaign between the two camps over support for Medicare and the war in Iraq.

At the same time, Kerry found the form that had eluded him in the early stages of the campaign. Kerry essentially wiped his slate clean by moving to Iowa, rechristening himself the "Real Deal," and presenting a more forceful and decisive face to the voters of Iowa. The tortured balancing act between his opposition to the Bush administration's foreign policy and his vote to authorize the war subsided as the media and the other candidates trained their focus on the new front-runner, Howard Dean. In the two weeks before the caucuses, Kerry drew bigger and bigger crowds to his appearances, surrounded himself with firefighters and veterans, and presented himself -- to great effect -- as the only candidate who could "stand up" to President Bush on the issue of national security.

And Edwards, who was also lagging badly in the polls just a few weeks ago, snuck back into contention by presenting himself as the nicest candidate in the race -- and one who abstained from negative campaign ads -- even as his opponents savaged each other. This was a particularly effective strategy in Iowa, whose voters traditionally punish negative campaigning. But like Kerry, Edwards also relied heavily on an electability argument, saying frequently he was the only candidate who could beat Bush in the South.

But even many Iowans were shocked by the degree to which support was shifting at the 11th hour. At the Walnut Creek Community Church in the Des Moines suburb of Windsor Heights, 167 Democrats gathered to go through the process of caucusing. After a brief review of the rules, and a passing of the envelope for contributions to the local Democratic organizations, caucus chairwoman Angie King asked for a show of hands before separating the participants into preference groups.

Three results elicited reactions. John Kerry, who had 46 supporters, drew a few cheers. Edwards had 79, drawing applause and louder cheers. But the truly shocking result was for Dean: 20. Under the rules of the Iowa caucuses, that rendered him unviable, putting his supporters in the same category as Dennis Kucinich (five) and Joe Lieberman (two, whom the chairwoman rather pointedly sent out into the hall, because Lieberman, like Clark, had skipped the Iowa contest).

Maria Mattiace, a young local and an Edwards supporter, told what must have been a typical story: "I started out liking Gephardt because of his passion," she said. "But then I heard Edwards speak, and I just decided he's the one. I also liked Dean at one point, because he was willing to stand up to the government, but I don't like his arrogance."

Shortly afterward, at Kerry headquarters, there was jubilation as the reality set in about what was happening. In front of one of the televisions in the upstairs lobby, Drew Whitlow stood pumping his fist and whooping. Whitlow was a gunner on Kerry's fastboat in Vietnam, and had come up a few days ago from Arkansas to make calls to Iowa veterans for the campaign.

"We're off and running," he said. "More surprises to come."

Asked if he planned to travel to other states to do more volunteer work for "Comeback Kerry," he smiled and said, "Anything for the boss."

Shares