As U.S. courts take an increasingly skeptical look at the long-held belief among journalists that they enjoy a special privilege when it comes to protecting their sources, two high-profile legal skirmishes are addressing that very issue. Unfortunately for advocates of a free press, these battles don't involve stirring instances of media courage, but stories that exemplify what many believe is wrong with journalism today.

"We often have to defend the principle of protecting sources on the least appealing grounds," says Geneva Overholser, a professor at the University of Missouri Journalism School and a former editor of the Des Moines Register. "We can't pick the circumstances. If we could, we'd pick cases prettier than this."

The press's working model for confidentiality has often focused on government employees who risk their careers in order to help uncover a gross injustice that would have otherwise remained hidden. Think of Daniel Ellsberg leaking the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times, or the Washington Post's Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein protecting their Watergate sources more than 30 years later.

But what about sources who hide behind their confidentiality agreements and mislead reporters to score political points via the press? What about those who lie or break the law with their disclosures? As Los Angeles Times columnist Robert Scheer recently noted, the argument for confidentiality "is undermined by the increasingly common practice of government sources using reporters to spread falsehoods or discredit foes, knowing reporters will hide their identity."

It's hard to find much public good that has come from either of today's simmering sourcing controversies: a lawsuit over New York Times stories accusing scientist Wen Ho Lee of espionage, or the Justice Department investigation into who leaked the name of CIA operative Valerie Plame to conservative columnist Robert Novak. Taken together, they create "one of those situations where people are holding their noses because the stench is so bad," says Aly Colon, ethics group leader at the Poynter Institute in St. Petersburg, Fla., a school for journalists. "But the consequences of not defending the principle that you've made a promise is even worse. Because if you don't defend the ones that stink, how do you defend that ones that don't?"

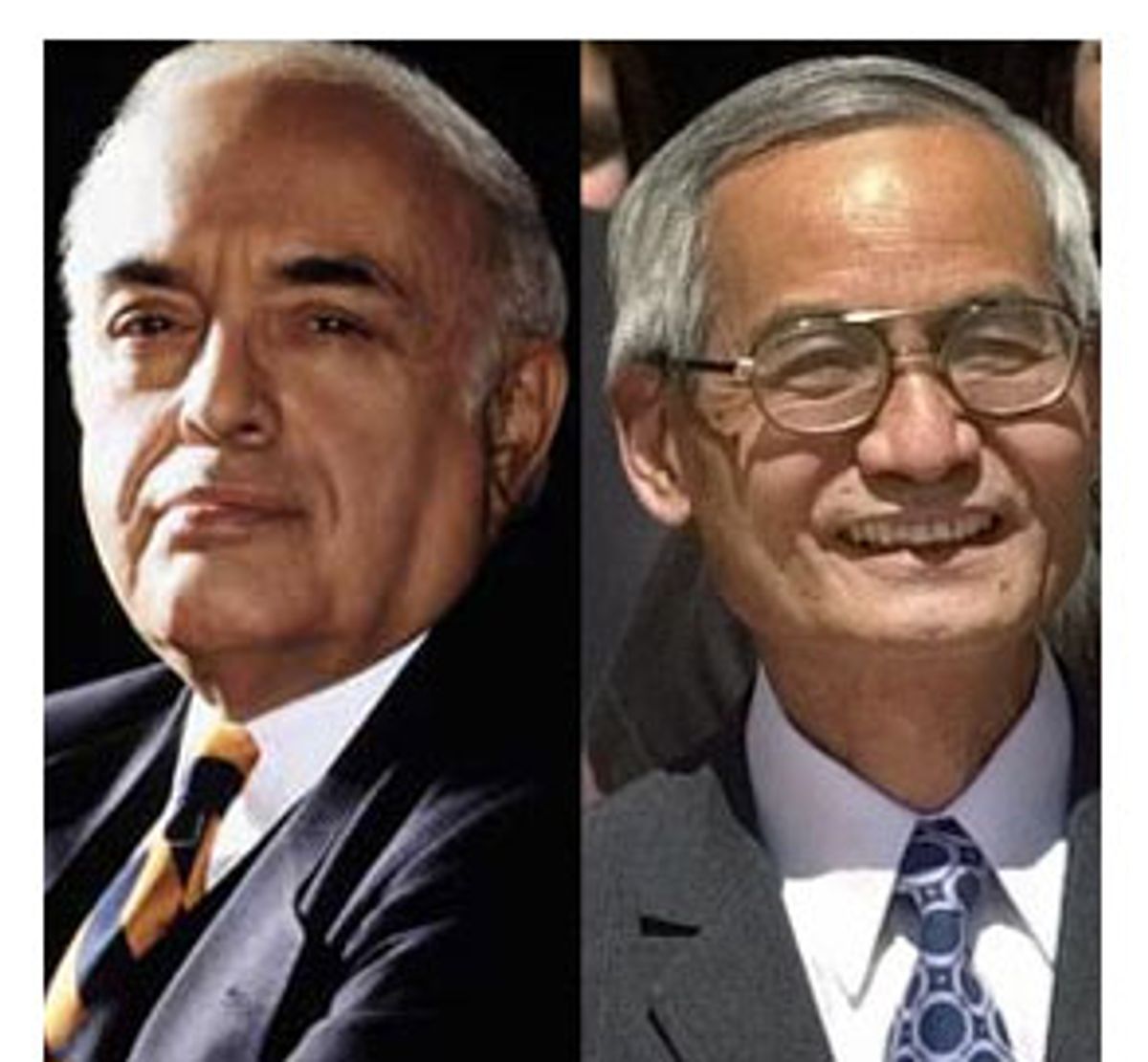

Wen Ho Lee is the scientist at the Los Alamos nuclear laboratory who was accused of espionage in 1999, and who for months was the subject of damning reports by the New York Times' Jeff Gerth and James Risen. Their work often reflected -- as fact -- the views of a key source, Notra Trulock, the Department of Energy intelligence official who had been shopping his conspiracy theory about Lee -- and about the Clinton administration's refusal to catch an "obvious" communist spy -- to various government officials and agencies for months before the Times embraced it in the spring of 1999. A one-time contributor to the right-wing chat site Free Republic, and now an associate editor at the right-wing media watchdog group Accuracy in Media, Trulock's political agenda is well known.

The problem for the Times turned out to be that virtually none of the allegations that Trulock helped lay out for the newspaper were true. One year later, after the Times' front-page accusations about spying at Los Alamos, government prosecutors, who once claimed Lee had downloaded the "crown jewels" of the nuclear defense system, agreed to free Lee if he pleaded guilty to one count of improperly downloading classified material to a non-secure computer.

Lee is now pursuing a Privacy Act lawsuit against the U.S. Energy Department and Justice Department, alleging that government officials supplied reporters with private information about him and suggested he was a suspected spy. "The New York Times stirred up a big hornet's nest," says Lee's attorney, Brian Sun. "Dr. Lee was damaged in a way that's irreparable. He can't recover his reputation after being identified in the press as a spy."

To prove government liability, Sun wants reporters to divulge their sources, and to date the presiding judge agrees, recently waving off journalists' objections that their sources should be protected. Not if the sources violated the Privacy Act in the process of leaking, wrote Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson of the U.S. District Court in the District of Columbia.

The Times stands at the center of the case. Up until the Jayson Blair fiasco last spring, the Times' worst-case-scenario coverage of the Lee saga stood as perhaps the paper's most embarrassing reporting episode of the last quarter-century. Fast-forward five years later and Times reporters are facing the prospect of jail time for protecting the same politically motivated sources who helped embarrass the paper in the first place.

"It's insult to injury," notes Ian Hoffman, coauthor of "A Convenient Spy: Wen Ho Lee and the Politics of Nuclear Espionage." "This case is ugly all the way around. But those reporters have to stand by those agreements. Even if it appears as though the information they received turned out to be incomplete or tilted to manipulate them, that's what they're stuck with. It ought to give everyone pause about using confidential sources."

The other high-profile case is hardly more appealing. It centers on the ongoing Justice Department investigation into senior Bush administration officials leaking the identity of an undercover CIA operative to Robert Novak, who published the information in a July 14 dispatch. In his column, Novak mentions "two senior administration officials" as his sources.

The agent was Valerie Plame, whose husband, former U.S. ambassador Joseph Wilson, was given a sensitive CIA mission of going to Africa in 2002 to investigate the claim, mentioned in a Bush State of the Union Address, that Iraq was trying to obtain uranium from Niger. Wilson concluded that the charge was baseless and he soon became a public critic of Bush's case for invading Iraq. In hopes of undermining Wilson's credibility, some inside the administration tried to advance the story that Wilson was picked only because of his wife's position at the CIA.

Six other journalists, including ones at Time magazine, NBC and MSNBC, reportedly received the same tip. But Novak was the only journalist to print it, complete with Plame's identity. For now, Novak, who refuses to name his sources, is protecting administration officials who not only misled him on the facts but may have also broken the law to score political points.

"It's clear to me he's allowing himself to be used by what now seems to be a spectacularly inappropriate and illegal effort by the White House to discredit [Wilson] by revealing Valerie Plame's name," says Overholser. She notes the stalwart Republican columnist "is participating in something that was illegal and should say who the source was. But it's a political and ideological decision he's made not to do that."

Novak is not alone in his dilemma. The other journalists who reportedly got the tip could come forward, even anonymously, and identify the administration leaker, particularly if they feel senior administration officials breached the Intelligence Identities Protection Act by uncovering a covert CIA agent. According to the Supreme Court's 1972 ruling in Branzburg vs. Hayes, the last time the high court dealt with the issue of the press's privilege, reporters may be compelled to testify if they witness a crime being committed. In Branzburg the court, while setting aside some exemptions, ruled that the public's right to that kind of information took precedence over a reporter's need to protect sources.

Novak himself insists he broke no law by leaking Plame's identity. In a follow-up column, he suggested he was wrong to refer to Plame as an "operative," and that sources subsequently told him she was simply an "analyst" -- which would mean that even though he got the story wrong, he broke no law, because it's not illegal to identify CIA analysts, only operatives. That fallback theory has crumbled, though. As even the conservative Washington Times made clear, "reports are incorrect in reporting that Mrs. Wilson is an analyst whose identity would not be protected" by law.

If investigators determine the leak constitutes a crime, Novak could be called to testify before a grand jury. "I don't think Novak would cooperate," says Lucy Dalglish, the executive director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, which represents journalists ensnared in legal showdowns over sources. "And the most likely outcome would be major fine and jail time."

The idea of Novak, or the Times reporters, being turned into martyrs for their questionable work makes some press advocates uncomfortable. "We're not defending Novak's right to out a CIA agent or the New York Times' right to characterize Wen Ho Lee in a way the government had to apologize for," stresses Colon at the Poynter Institute. "Those journalists and news organizations have egg on their face." Rather, he and others want to defend the general right of the press corps to work without fear of being subpoenaed.

"I agree they're unattractive cases," adds Kevin Goldberg, legal counsel for the American Society of Newspaper Editors. "But it would be nice if people looked beyond that to see reporters trying to do the right thing" in protecting their sources.

George Freeman, assistant general counsel for the New York Times Co., agrees that the big picture ought to take precedence. "The ins and outs of the reporting and the outside criticism [of the Lee coverage] really doesn't have any bearing on the situation," he says. "The protection of the principle is the overriding concern."

"Reporters can't maintain their credibility unless they keep their promises to sources," notes Dalglish, at the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. "A journalist's word is his bond. And if you break your word, who's going to talk to you again? The chill for those gathering information is a real threat."

The other threat is coming from the courts. Along with Jackson -- who decided in the Lee case to force journalists to cooperate -- another U.S. District Court judge, in August, ordered authors working on a book about Irish terrorism to hand over tape-recorded interviews with a suspected terrorist so they can be used in a trial in Ireland. Fearing they might lose the legal battle and that the case would become precedent setting, the journalists surrendered their tapes.

Despite the concession, Judge Richard Posner of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit in Chicago went ahead and issued a full-fledged ruling, taking aim at the press's privilege of protecting nonconfidential sources -- their refusal to share background information on people they write about. "We do not see why there needs to be special criteria merely because the possessor of the documents or other evidence sought is a journalist," Posner wrote. Two dozen media organizations quickly filed a friend-of-the-court brief, calling Posner's opinion a "stunning break from long-standing precedent" that was "far-reaching and radical."

Still, the unsettling details of the Lee and Plame controversies have opened a debate within the journalism community as to whether protecting sources always makes sense.

"Guaranteeing our sources that we won't out them is a terribly important principle," says Overholser, former ombudsman for the Washington Post. But when considering whether to maintain agreements of confidentiality, "reporters should at least take into consideration if they've been badly used. If they've been lied to, are they still going to protect their source? That's an odd ethical bond. Why protect somebody who spun you and endangered somebody's livelihood, which was certainly true in the Wen Ho Lee case." Nonetheless, Overholser concedes she's torn because if reporters do make exceptions, the courts could take that as evidence that a blanket privilege for the press is unnecessary.

Wilson, a government servant for 25 years, says he strongly defends the press's First Amendment rights. But the Lee case and the leak surrounding his wife are instances "where sources misled the press," he notes. "That's a different story. What retribution does the press take on a source who misled them? The question is, will the press allow itself to be used even more as a tool of disinformation than it already is?"

One option is voluntarily outing the source. Press advocates argue that's career suicide. But just three years ago Novak himself publicly revealed a confidential source: FBI agent Robert Hanssen. After Hanssen was arrested for espionage, Novak wrote that "in order to be honest to my readers, I must reveal" that Hanssen had been an unnamed source in prior Novak columns. Novak feels no such necessity today to reveal the identity of the sources who unmasked a CIA operative's undercover status.

But Dalglish fears that if journalists start making exceptions, the courts could soon take the privilege away altogether. "If a source behaves unethically, I think the responsibility of the reporters is to say to the source: You screwed me over. I'm never going to trust you again and don't come to me looking for favors. I'm going to keep my promise but I'm going to report the truth and the record will be clear including that the information you gave me is false."

Critics, however, argue that in the Lee case the Times never did that. In response to external criticism, the paper did go to the unusual lengths of publishing an "assessment" of its Lee coverage, in September 2000. But the defensive letter from the editors, while finding some fault with the "tone" of the paper's work, essentially stood by the Times' reporters. Jay Rosen, chairman of the Journalism Department at New York University, calls the assessment "one of the most tortured and strained notes ever to appear in the pages of the New York Times."

It was the Times' now-infamous March 6, 1999, story that set the Lee saga into motion. In retrospect it seemed to be a classic case of reporters becoming captives of their sources, to the point of not even considering alternative explanations: that is, that Lee was innocent. Although it did not name Lee (that came three days later), the 4,000-word story, "Breach at Los Alamos -- A Special Report: China Stole Nuclear Secrets for Bombs, U.S. Aides Say," made it clear Lee was the prime suspect in what the paper called a historic bout of communist espionage, and one that the Clinton administration had dragged its feet in uncovering.

At the time, the sensational story dovetailed nicely with a previous Times exposé on the alleged transfer of satellite technology to China by two U.S. defense contractors, and how the Clinton White House had granted a key launch waiver to one of the companies, Loral, simply because the chairman was a longtime contributor to the Democratic Party. Once granted that waiver, the Times asserted, Loral leaked military secrets to the People's Republic of China. Neither charge proved to be true.

Relentlessly prosecutorial in tone, the March 6 story often, in unqualified terms, referred to "the espionage," "the leak," "the theft," and "the crime" leaving readers no room for doubt. Interrogating Lee the next day at Los Alamos without an attorney present, FBI agents waved the Times article around. "You know, Wen Ho, this, it's bad," said one agent. "I mean, look at this newspaper article! I mean, 'China Stole Secrets for Bombs.' It all but says your name in here."

The Times story also quoted an anonymous source saying that the suspect, a Chinese-American Los Alamos computer scientist who failed a polygraph the previous February, "stuck out like a sore thumb." It was just one example of how the Times was misled by its sources, chief among them Trulock. Although never described as a source, the Times' March 6 story certainly mentioned Trulock positively: "In personal terms, the handling of this case is very much the story of the Energy Department intelligence official who first raised questions about the Los Alamos case, Notra Trulock."

That's one of the odd aspects about the ongoing Lee case and its search for government leakers. Because unlike the Novak controversy, which remains for now an actual whodunit, most people who follow the Lee story feel as though they know who some of the key sources in the stories were, such as Trulock. "It's one of the worst-kept secrets," says Hoffman. Yet the Times' reporters refuse to confirm that fact in court.

Journalists ordered to provide depositions, along with Gerth and Risen at the Times, are Robert Drogin of the Los Angeles Times, Josef Hebert of the Associated Press, and Pierre Thomas, formerly of CNN. None of the Lee news coverage in those outlets was nearly as accusatory as the Times' stories.

None of the journalists have answered questions about their sources, refusing to even say which government agency the sources worked for. Lee's attorney, Sun, is expected to return to court in early February to ask that the journalists be held in contempt. Attorneys for the reporters are expected to argue that Lee's legal team has not exhausted its search for the source and that more depositions from non-journalists are needed. If the judge rejects that plea, reporters would soon be brought in and cross-examined and could ultimately face jail time if they refuse to cooperate.

Meanwhile, according to news accounts, the Justice Department investigation into the Novak leak has been gaining momentum in recent weeks as well, and a grand jury may be called to hear testimony. Punctuated by the announcement on Dec. 30 that Attorney General John Ashcroft was recusing himself from the case, investigators continue to zero in on the White House as the primary source of the potentially illegal leak.

Yet the investigation remains in the early stages, with lots of scenarios still possible, including Novak's being ordered to testify. And complicating factors remain, such as Justice Department guidelines that discourage subpoenaing reporters for grand jury testimony. Also, it's not entirely clear the Plame leakers breached the Intelligence Identities Protection Act, a law that nobody has ever been prosecuted under. Some Novak supporters argue that to be guilty, the leakers would have had to know Plame's precise CIA status and then passed it along to a reporter in hopes of blowing her identity. If they simply told Novak that Wilson's wife worked for the CIA and didn't consider the consequences, then it's conceivable a judge or jury would find that a crime was not committed.

Wilson notes it was the CIA itself that asked for an investigation in the first place. "I don't believe the CIA would have referred this case to the Justice Department unless it thought a crime had been committed," he says.

Quietly watching the unfolding drama are the journalists who reportedly received the same information about Plame. Should they come forward? Overholser doesn't think so. "Those six received the same information as Novak and made an admirable decision not to use it," she says. "Perhaps they questioned the import, or thought the leaker was behaving in an unsavory way. But I think their decision not to use it takes them off the playing field."

And Colon notes, it hasn't been established yet that the law was broken. "Maybe we'll find the information wasn't disclosed illegally," he says.

But what if Justice Department investigators announce tomorrow that they concluded leaking Plame's name was a crime and asked for the cooperation of anyone with relevant information? "As an editor," says Overholser, "that's when I'd call [the newspaper's] lawyer. Because then it becomes a more complicated legal matter and not simply a journalistic decision that a reporter has to make for him or herself."

Russell Weaver, a professor of law at the University of Louisville, says under those circumstances, the six journalists who know the leaker's identity would almost certainly be subpoenaed to testify before a grand jury. And because the case is being handled on a federal level, which means state-based shield laws would not protect the reporters, they would be forced to reveal the information or face jail time, says Weaver.

For press advocates, the unappealing specifics of the Plame and Lee cases remain less compelling than the larger privilege at stake. "Whether or not Novak behaved in an appropriate way, I'm not going to go there," says Dalglish. "The same thing with New York Times and the Wen Ho Lee case. But I'm perfectly comfortable defending reporters' rights to keep their source information confidential."

Shares