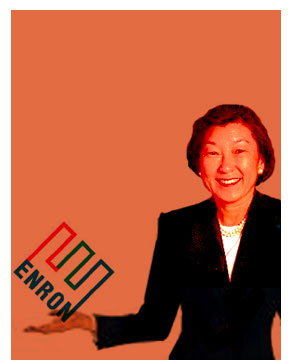

More than two years after its spectacular bankruptcy, Enron remains synonymous with the wave of corporate scandals that torpedoed stock prices and investor confidence. Guilty pleas from Andrew and Lea Fastow notwithstanding, Enron executives have mainly remained silent. But one key Enron director has spoken out — to defend the practices that left her rich and Enron shareholders broke.

Wendy Gramm, a member of the Enron audit committee that approved Fastow’s shady partnerships, filed one of the reported record 12,000 public comments on the Securities and Exchange Commission’s proposal to tweak the rules for choosing corporate boards of directors. The SEC proposal grew out of a consensus that, thanks to a Soviet-style election system that effectively sidelines shareholders, directors were neglecting their legal duty to investors to oversee managers, creating a climate conducive to corporate scandals. For example, the failure of Enron’s board of directors in general, and its audit committee in particular, led to the company’s stunning bankruptcy, vaporizing stockholdings once valued at $90 billion.

You’d expect Wendy Gramm, now head of the Regulatory Studies Program at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, to recognize that the Enron board’s extraordinary failure indicated a dire need for reform. You’d be dead wrong.

Gramm thinks the system works just fine. After all, she pocketed an estimated $2 million as an Enron director.

Gramm joined Enron’s board after chairing the Commodities and Futures Trading Commission, where she issued regulations that legalized the type of electricity trading that helped Enron make millions in illegal profits (on Gramm’s watch as a director). As a member of Enron’s audit committee, Gramm found nothing wrong with accounting tricks that inflated earnings and siphoned money to selected executives in violation of company rules, if not federal laws. Coincidentally, Enron also delivered campaign cash to Gramm’s husband, former U.S. Sen. Phil Gramm of Texas, and now provides that arch opponent of big government with his first private-sector job in decades at the Swiss bank UBS, which owns the rump of Enron’s energy trading operations.

Wendy Gramm’s comments to the SEC combine her signature knee-jerk dismissal of any government regulation as unnecessary and potentially harmful with this analysis of how boards of directors should function vis-à-vis investors:

“Boards who [sic] consistently operate at variance with shareholder interests (i.e., who do not maximize share values) will see the values of their firm’s shares fall, other things equal. As the shares become cheaper, the firm becomes a more attractive target for takeover. Even barring takeover (because of, say, a poison pill provision), a persistent abuse of shareholders interests must eventually result in bankruptcy. In either instance, assets will be stripped from the self-dealing board’s control and surrendered to others who may be better able to enhance share values. Indeed, the recent spate of corporate scandals has, if anything, provided vivid testimony as to how quickly and efficiently this market process works in practice.”

In other words, Enron’s bankruptcy was a triumph of market efficiency. Gramm’s vision understandably ignores directors’ fiduciary duty to shareholders; she ignored it while sitting on Enron’s board, too, so at least she’s consistent. She’s opposed to regulations that might give investors tools to ensure that directors perform their legal oversight obligations; the market demands that shareholders watch helplessly if executive malfeasance skins the value of their holdings toward zero (and vultures like UBS can get the bones cheap).

While she preaches living by the market’s risks and rewards, Gramm found a pretext to avoid that risk herself while making decisions that helped bankrupt Enron.

In 1999, Gramm declared that owning Enron stock presented a conflict of interest with her duties as a director. That assertion is pure drivel, violating basic common sense and norms of good corporate governance; directors legally bound to protect investors should be investors, too. By Gramm’s logic, only non-citizens should be lawmakers or judges, so their decisions won’t be tainted by having to live with the consequences.

Gramm’s ludicrous claim made sense in one context: It provided a convenient alibi to cash out her Enron shareholdings for $300,000 and to insist on getting paid in cash while she was approving the company’s secret steps along the financial precipice. When Enron went over the cliff, the Gramms even portrayed themselves as victims: Wendy’s stand on her imaginary moral high ground led her to sell before Enron’s price peaked, they whined, so she forfeited some potential profits. Enron employees lacking Gramm’s finely tuned ethics, and the rest of the investing public lacking her inside knowledge of the company’s twisted finances, were left holding worthless paper.

As Gramm sees it, if you lost your retirement savings or your job because you trusted me to do my duty, quit whining: That’s how markets work. My friends and I made lots of money because we kept government regulators out of the markets and rigged things in our favor. Don’t introduce even a hint of democracy into voting for corporate directors that might prevent us from doing it again.

It’s sad to see this argument on the letterhead of George Mason University. The real George Mason was a passionate defender of democracy with a claim to be the first American shareholder activist. Mason protested strongly in 1763 when the British government unilaterally revoked the charter of the Ohio Company, where he served as a director. Mason exhorted those who accept the responsibility of serving on boards “never to let the motives of private interest or ambition to induce them to betray, nor the terrors of poverty and disgrace, or the fear of danger or of death deter them.”

It would be great to hear Wendy Gramm explain her work at Enron to Mason — or to the public, for that matter — instead of hiding behind his name to take cheap shots at reform that might prevent abuses from which she personally profited.