The other day, on a trip to the Ministry of Public Works, I sat in an unmoving car with my driver and translator. A mysterious but typical snarl up ahead had turned the road into a parking lot. Frustrated drivers U-turned over a median, edged their cars into wrong-way traffic, jumped sidewalks in misguided attempts to escape the mess. "Look at this," said Amjad, my translator. "They think democracy means you can do whatever you want." Inevitably, a fender scraped a door panel. Men jumped from their cars and began shouting and shoving in the ribbons of space between vehicles. One guy went for his tire iron and waved it like a sword over his head. Before things got truly ugly, Iraqi traffic cops came running from somewhere nearby and calmed the situation by directing the cars, gesturing with their Kalashnikovs. Eventually, the mass untangled and the cars continued to edge toward their destination.

Amjad's take on the Iraqi definition of democracy is certainly simplistic, but it's not completely out of line. Iraqis tell me all the time that they don't understand what democracy means. So far, they associate the word with chaos and the freedom to do whatever the hell you want. That's not democracy as Americans understand it, but the confusion is understandable. Since before the war, the United States had been promising the Iraqi people that Saddam's ouster would be followed by a wee bit of occupation and a whopping portion of democratic nation building. So far, the opposite has been true.

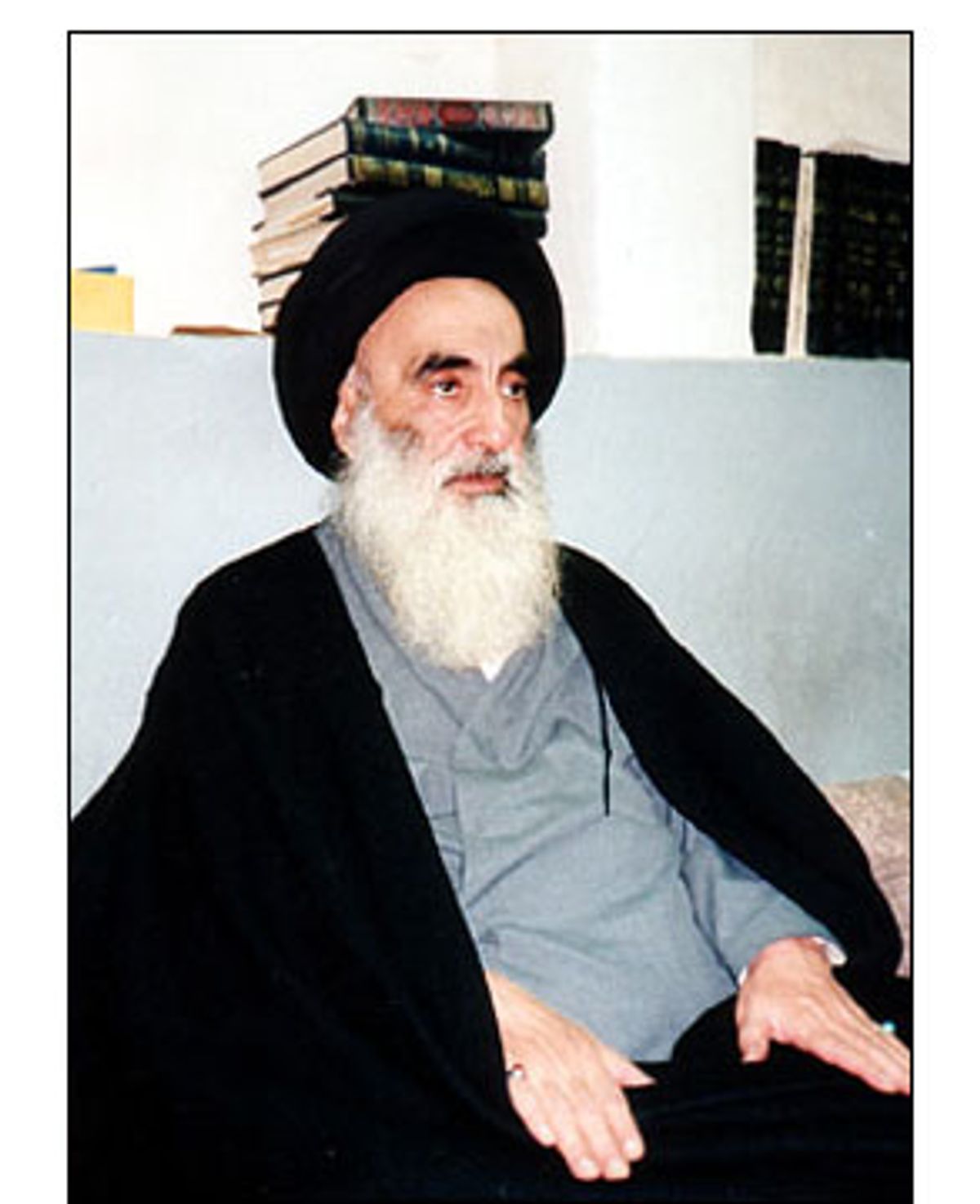

In the next few months, Iraq and the United States will be struggling to figure out what the handover of power will look like. A few weeks ago, Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, Iraq's most respected Shiite leader, demanded free and open elections in lieu of the caucuses the U.S. favors to create a transitional government at the end of June. In Najaf, Basra, Baghdad and other towns around the country, tens of thousands of Iraqis demonstrated in the streets to pressure the U.S. to pay attention to the Shiite religious leader's demands. And it worked. Proconsul Paul Bremer returned to the United States to confer with the Bush administration and ask the United Nations, which had pulled out of Iraq after a devastating Aug. 20 bombing destroyed its headquarters and killed its top official in the country, to reinvolve itself in Iraq -- specifically to see if elections are possible. Since then, U.N. chief Kofi Annan has announced that, as long the United States can provide proper security, the United Nations will, indeed, return.

In theory, open elections represent the most democratic option for Iraq. But there's a problem. Shiites constitute a majority in Iraq, with 60 percent of the vote. And while Sistani and his followers aren't gunning for a full-out theocracy at this point, followers of his that I spoke with indicated that a Shiite-dominated government would do its best in the long term to shift the nation toward Islamic rule. That could lead to the marginalization of minority groups such as the Kurds, Christians and Turkmens, not to mention the Sunni Arabs who ruled the country under Saddam's long reign. It could greatly compromise the rights that women maintained under Saddam's secular (albeit dictatorial) regime. And it could completely screw up the Bush administration's hopes of fabricating an ally smack-dab in the middle of the Middle East. (To be honest, such an alliance may be a long shot no matter what the political outcome is.) In a worst-case scenario, hardline Islamic rule could mean the abrogation of future elections and a theocratic state. In other words, the democratic process might result in the death of democracy. It's a scary prospect for the Bush administration, which is scrambling to keep everything at least looking like it's under control until the U.S. election in November.

Earlier this week, I made a trip to the holy city of Najaf, a few hours south of Baghdad. Najaf is the religious epicenter for Shiite Iraqis and indeed Shiites around the world, because it's where Imam Ali, godfather of the Shiite sect of Islam, is buried. Sistani maintains his headquarters there, as do most Shiite leaders, though they have satellite offices in Baghdad and other parts of the country.

On the drive to Najaf, I asked Amjad (who is Shiite) about Sistani and the control he is suddenly wielding over the United States and its plans. As a rule, Amjad told me, Sistani doesn't involve himself in politics. He focuses purely on religious issues. It's part of the reason he garners such respect. Iraqis see Sistani as someone driven by the welfare of the Iraqi people, not by personal ambition or desire for glory. (By contrast, many Iraqis mistrust most members of the Iraqi Governing Council, believing that they made Faustian bargains with the United States.). Since the end of the war, Iraq has been suffering from a major leadership vacuum. Sistani (who has indicated he will not occupy political office) is stepping into the breach until someone else emerges, Amjad said.

As we neared Najaf, I began seeing posters, billboards and large hand-painted portraits of Sistani (as well as pictures of famous Shiite martyrs). He is an older man with a full white beard and sharply peaked dark eyebrows, wearing the black turban-like emama worn by Shiite religious leaders. During the day, the road to Najaf is busy and relatively safe. We passed through a number of checkpoints where Iraqi police and soldiers asked my driver, Thamer, whether the car belonged to him (car theft remains one of the many major security issues here). A simple "yes" got us waved through. The method seemed pretty flawed to me, but Thamer said the police look for telltale signs of nervousness or evasion and base their decision on intuition.

Traffic became heavier on the outskirts of the city, as cars, dilapidated passenger vans, and smoke-belching buses converged on the city center. On top of many of the vehicles lay plain wooden coffins lashed to the luggage racks, some partially covered with blankets that had been disordered like bedcovers by long highway trips. Just about every Shiite Muslim who dies in Iraq (and many who die in other countries as well) is brought to Najaf for burial in a cemetery so large it is supposedly visible from outer space. The cemetery begins along one of the city's main roads and sprawls over the outskirts like an endless subdivision of miniature houses. Steamer trunk-sized burial markers are so tightly packed together that it seems impossible a body could fit beneath them. Only a few roads snake through the cemetery. Amjad's father is buried somewhere in there. Amjad told me that the last time he came to the cemetery, he found it nearly impossible to locate his father's grave site.

We drove down a boulevard lined with squat glass-and-cement tourist hotels and parked buses that seemed on the verge of shedding one or more parts. Since the end of the war, Iranian Shiites have begun making tourist visits to the holy city, crossing easily over the once-restricted border, which is only a little more than 150 miles away.

Sistani will not speak directly to the press or members of the Coalition Provisional Authority (another reason he holds such respect among his followers). He sometimes speaks through representatives, but on the day I went to Najaf, recent articles in the Western press had left the Sistani camp feeling frustrated and misquoted. One cleric told me that, if I waited until 8 p.m., I could submit some questions in writing. Making the three-hour trip back to Baghdad late at night would have been very stupid -- a significant number of hijackers haunt the roads then -- and since Sistani rarely answers such questions anyway, I begged off.

Instead, I met with the spokesman for Ayatollah Bashir al-Najafi, one of the three most important Shiite leaders in Iraq apart from Sistani. (The others are Mohammed Said Hakim and Mohammed Ishaq Fayyad). The three lesser leaders all command significant numbers of followers and their teachings differ from Sistani's in modest ways. But overall, they and their followers acquiesce to Sistani's ultimate authority (especially now, since they've put on a united front to deal with the Americans). This is not necessarily the case with Muqtada al-Sadr, a young Shiite cleric whose popularity derives foremost from his legacy as the son of Muhammed Sadiq al-Sadr. In the 1990s, the older al-Sadr gained a significant following by defying Saddam Hussein's iron-fisted anti-Shiite edicts (for instance, his attempt to forbid Friday prayer). Saddam had him assassinated in 1999. Though Muqtada does not have his father's seniority or clout, he's shown he cannot be ignored. Shortly after the end of the war, Muqtada organized large anti-American protests and, at one point, attempted to set up his own alternative government. Shiites tell me that, in general, he is not widely respected. But he has served as the focal point for anti-American sentiment and, these days, that means a lot. Lately, though, he has dropped somewhat from the scene. I've heard that he's being checked somewhat by Sistani's influence, but I cannot say that with certainty.

Bashir's headquarters are in the old section of the city. Sand-colored brick row houses with metal doors bordered the streets. In front of one, a skinny boy worked a large piece of sandpaper over a wooden headboard propped on sawhorses. A man in a brown pinstriped dish-dash robe and matching suit jacket walked along carrying a plastic bag of vegetables in one hand and a string of prayer beads in the other. As we parked the car, two very young boys in sweat suits rode past in a small donkey cart pulled by a smaller donkey. A pair of women walked down the street wearing abayas -- the head-to-toe black covering favored by conservative Muslims. In Baghdad, less than half the women I see wear the abaya but every woman I saw in Najaf had one on.

I had dressed in full loose clothing and brought a scarf to cover my hair. Most of the time, I don't wear a hijab (headscarf) -- it's just not necessary. In Najaf, it would have been highly insulting, to both men and women, to go without one -- the equivalent of wearing a bikini to Sunday mass. (Since yesterday, when I wrote this, I've had a bit of a policy shift. I've started to wear a scarf in the car and out on the street for safety reasons. Three days ago, armed attackers pulled alongside a car carrying a mostly Western CNN crew and opened fire, killing two Iraqi CNN employees. One of the men killed was the cousin of a friend of mine. He told me that, in the interest of keeping as low a profile as possible, I should wear the scarf. Sadly, he's right.)

In the foyer of Bashir's headquarters, we were thoroughly searched by men carrying guns of various sizes. They temporarily confiscated a small pocketknife from my bag and led us to the office of Abu Saduk, Bahir's spokesman. We passed along the edge of an empty room with a well-worn carpet that was used for prayer. At the open door of the office I paused to take off my boots before entering. I had planned poorly for the trip, wearing high boots that required me to perform some spastic gymnastics to remove them. Eventually I freed myself and entered the room from which Abu Saduk had been watching me with a granite expression. He nodded in greeting as I came in -- a solid man with an oval platter face and thick black beard who looked to be in his 30s. He sat on the floor behind a legless desk and I sat on the floor along the wall to his right. As we were exchanging greetings, an assistant arrived with small glasses of the strong, sweet, excellent tea that visitors are always offered in Iraqi homes or places of business. Through Amjad, who acted as interpreter, Abu Saduk told me that he would be tape-recording the interview. The heavy security precautions plus a fear of being misquoted felt oddly reminiscent of a trip to the Coalition Provisional Authority headquarters -- a place Abu Saduk will certainly never go.

I began by asking Abu Saduk what he thought about the American presence in Iraq. He shrugged and focused on the ceiling above my head. "Before we were ruled by the student," he said. "Now the teacher is ruling." Abu Saduk went on to explain that the United States was responsible for Saddam (backing him in his early days and providing support during the Iran-Iraq war). "The Americans came to Iraq for strategic and economic interests -- to secure the region for themselves. They cannot be trusted, nor can any election conducted during the occupation."

Before the war, Saddam persecuted -- often brutally -- the Shiites in Iraq. This is the reason that U.S. neoconservative strategists, whose starry-eyed optimism was not shared by scholars who actually knew something about Iraq and its people, assumed that the Shiite population would cheerlead the U.S. invasion and at least tolerate the occupation. Sistani's demands caught the United States off guard.

In the house I share with other journalists, we're constantly debating what Iraq's future will look like. One of our key questions is: Will the United States remain committed to rebuilding the country, or will it quietly retreat to secured bases, leaving most of the work undone -- in other words, repeating the Afghanistan scenario? One thing we all agree on: If the Shiites turn against the Americans -- if Sistani declares jihad, or holy war, against them -- the result will be a full-out armed uprising and the United States will be forced to pull out of the country. Civil war will follow, as the three major groups in Iraq -- the Kurds, Sunni and Shiites (previously repressed by Saddam) -- vie for control of the country. It's a pretty terrifying thought, and it's the reason Sistani has the United States over a barrel right now.

"Right now," Abu Saduk told me, "it [jihad] is not necessary. We hope that America -- a distant hope -- will keep its promises and leave Iraq."

Most Shiites I've spoken to say that the chances of Sistani's declaring jihad are incredibly slim, that such a radical step would be a last resort for the moderate cleric. And without his green light, I'm told, none of the other leaders would declare without him -- except, possibly, Muqtada, who doesn't have the authority to declare official jihad but could incite, if he chose, a dangerous uprising. Abu Saduk told me that such a decision would be made by many Shiite clerics working together.

I asked at what point he felt it would be time for a Shiite leader to discuss a unified resistance against the occupation. "I can't put a date," he said. "Maybe tomorrow, maybe six months."

We spoke for a while about his skepticism about the Americans' good intentions. He talked about the occupation in a calm and thoughtful way -- not with the vitriolic fervor the Western media portrays as innate to fundamentalist Muslims (a sadly inaccurate stereotype). While he spoke, he avoided looking at me, most likely because I was a Western woman whose headscarf kept slipping backward to reveal some unwelcome hairline. He acted less than friendly and even a little exasperated, reminding me of a particularly tough history teacher I had in high school. At one point, though, he interrupted himself to say, "I don't mean my words to hurt your feelings as a person -- I'm directing this at the government. I mean, if an Iraq government was occupying your country and ruling by whim, what would you do?"

On the one hand, Abu Saduk and millions of Shiites like him want the United States out of the electoral process, because they think the system of caucuses that the United States favors is just another way for the Bush administration to keep its fat thumb in the governing pie here. Under the cumbersome caucus system, the U.S.-appointed Governing Council will appoint local caucus officials to appoint a legislative body, which will then appoint all Iraqi officials. Not exactly an ideal democratic process. On the other hand, it's hard to believe that open elections would lead to anything except a Shiite government, and quite possibly a nondemocratic one.

Ostensibly, Sistani does not want an Iranian-modeled theocracy. And Abu Saduk told me that a Shiite-led government in Iraq would not look like Iran. But even if the clergy stayed out of the government, it's likely that Shiite policymakers would ultimately follow Sistani's dictates. And a shift toward Islamic law (if not Islamic government) would likely be the result. As Abu Saduk told me, Shiites wish to have a government of "God Justice" -- in other words, one that enforces Islamic law. Much as I respected Abu Saduk, I desperately hope he does not get his way.

A few weeks ago, a portion of the Iraqi Governing Council quietly voted to replace Iraq's existing family law, which is secular, with sharia -- Islamic law governing domestic issues. The vote means nothing without ratification by American Proconsul Paul Bremer, but as an indicator of what might happen in the future, it's very disturbing. Sharia puts decisions regarding issues such as divorce, marriage and inheritance in the hands of Muslim or Christian clergy, endangering rights that women have under family law.

Pascal Warda is a women's rights advocate in Iraq. She represents the Assyrian Women's Union -- one of the many women's rights groups that have formed here in Iraq since the end of the war. I met her at the office occupied by Nasreen Barwari, the minister of public works -- the only female minister appointed by the CPA. After the GC voted to abandon family law, the minister took to the streets to protest, along with over a hundred other women, including Pascal. Last-minute business had forced the minister to cancel our appointment, so I chatted with Pascal in the stale-smoked waiting area outside the minister's office. Dressed like a stylish New York mom in a blue suit and short haircut, she spoke animated, heavily accented English, though a bad cold had left her hoarse and snuffling. "Iraq is multiculture, multi-religion to be respected," she said. "If it's religious law, there's not respect for everyone." As an Assyrian Christian and a woman, she fears for her future under possible Islamic rule. "If we change to the Iranian experience, we've done nothing."

Pascal told me that she and other women's groups have been meeting with people in the CPA, including Paul Bremer, to try to make women's rights a priority. "We are fighting and fighting and fighting," she told me. "We believe we must do this for our daughters to be better off." Though opposed to the occupation in principle, Pascal wants the United States to stay in Iraq and oversee caucus elections to ensure that all factions of the population have proper representation.

Right now the United States finds itself in a "damned if they do, damned if they don't" situation. The future of this country, and the U.S. occupation here, look bleaker than ever. I do wonder sometimes whether President Bush wakes with a start every morning and asks himself why why why he had to go and invade Iraq. Things just haven't worked out as he hoped.

Involving the United Nations will help. It will not only placate the Shiites but will also make the blundering United States look better. No doubt the Bush administration will suddenly take the high road and say that strong U.N. involvement was exactly what was wanted all along.

Kofi Annan reportedly agonized over the decision to return the world body to Iraq. He knew that by doing so, he would be bailing out a leader whose beliefs and actions are a slap in the face to everything the United Nations stands for. But he made the right choice. The situation here is dire. It is vital that the United Nations get involved now. But if everything goes to shit and the Bushies hightail it out of Dodge, leaving the United Nations the fall guy, I will take advantage of the best Arabic insult I know and shave off their mustaches with my shoe.

Shares