Joe Trippi, the iconic architect of Howard Dean's Internet-driven campaign, is gone. And so are the millions of dollars that Dean raised from legions of grass-roots supporters over the last year.

Following defeats in Iowa and New Hampshire, and less than a week away from a make-or-break series of Democratic primary election contests, Trippi on Wednesday quit the Dean campaign after being offered a lesser position. At the same time, Dean announced that his high-flying campaign is broke, and he announced to workers that their paychecks will be suspended for two weeks because of a multimillion-dollar debt.

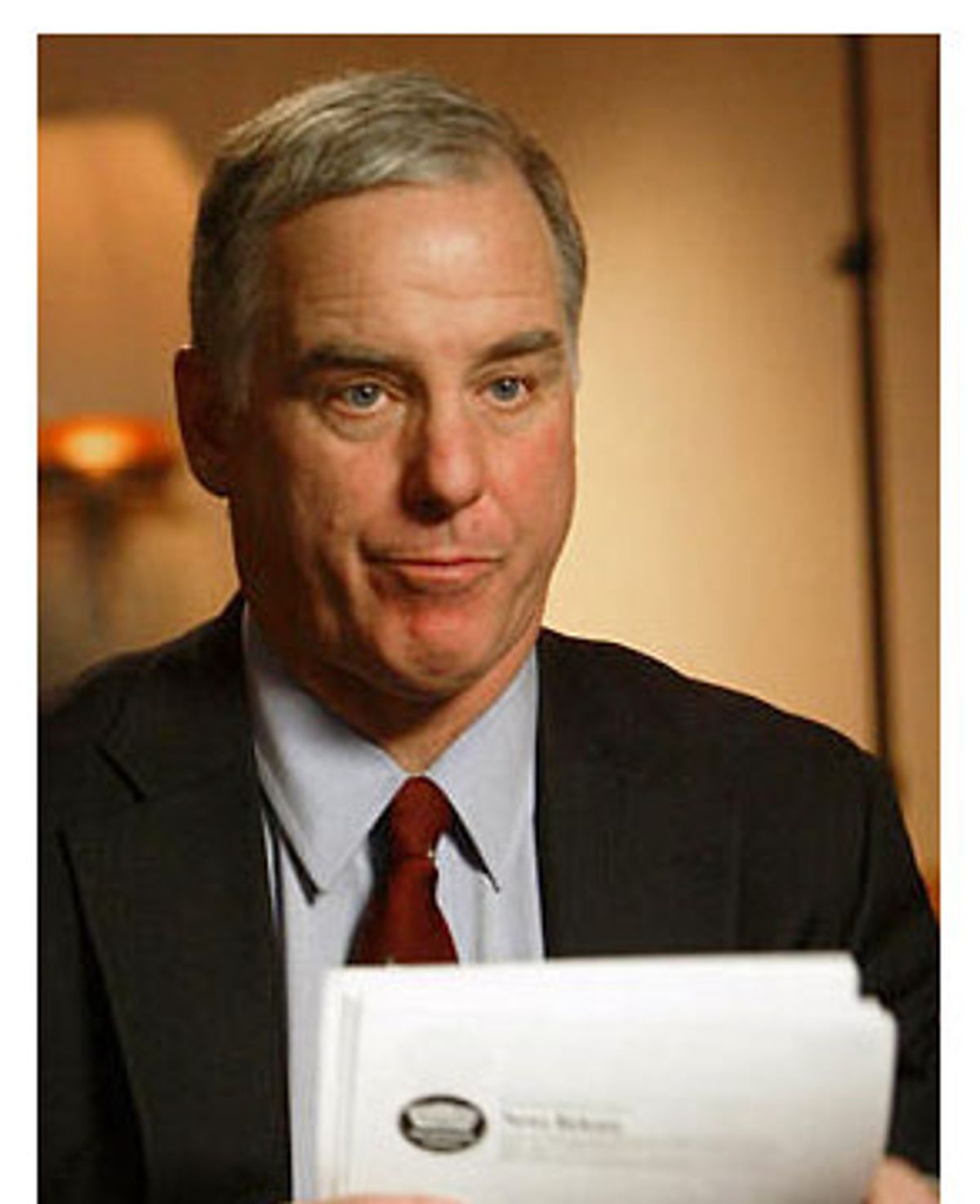

Roy Neel, former chief of staff to Al Gore, was appointed CEO of the campaign, supplanting Trippi, who served as a high-profile campaign manager, ad man and inspirational icon to many of Dean's Internet supporters.

It was devastating news for a candidate who, just four weeks ago, had been seen as the strong front-runner to win the Democratic presidential nomination. The campaign was basking in the glow of upbeat news coverage, fundraising prowess and endorsements from elected officials, labor leaders and celebrities. But after two decisive losses in the space of eight days, chaos that apparently had been percolating through the campaign organization broke into open view.

After Tuesday's clear defeat at the hands of Massachusetts Sen. John Kerry, Dean's "one remaining hope was to be able to pivot very quickly this week onto a sort of new substantive message," said Democratic consultant Howard Wolfson. "This is going to completely interfere with that."

The pessimism even had spread to many of the operatives and volunteers who staffed an organization known for its idealism and optimism. "The wheels are coming off the chassis," one said yesterday.

Even before Wednesday's shakeup, Dean had been undergoing a public, on-the-fly makeover -- tempering his language, making fun of himself on the David Letterman show and appearing with his wife, Judy Steinberg Dean, for an emotional TV interview. But the latest developments were more than cosmetic, and they made clear that a campaign once deemed unstoppable is now in very real danger of disintegrating.

Financially, donors wondering about the viability of the campaign are likely to hold onto their money. And critics are certain to question whether a candidate who could not manage the estimated $40 million he raised last year is capable of managing the world's biggest economy.

There will be political fallout, too. With a crucial, seven-state primary day coming Tuesday, stories about the campaign turmoil are likely to drown out Dean's appeals for votes. And with John Kerry coming off of two monumental wins, and with John Edwards and Wesley Clark moving into contests on friendly soil in the South and West on Feb. 3, prospects for the former Vermont governor are not bright.

While Dean was in Burlington Wednesday reorganizing his campaign and dealing with the fallout, front-runner Kerry and other candidates were already on the ground and courting votes in crucial states like Missouri and South Carolina.

The Dean campaign was a pretty disorganized affair from the beginning. That was almost the point: It was a "different" kind of campaign, driven by the candidate's refreshing spontaneity and consultant-free cadences, and fueled by the zeal of its idealistic volunteers and small grass-roots donations. That "roll with it" aspect carried over to the campaign's organization as well, which was roughly divided into three groups of the governor's top advisors from Vermont -- Kate O'Connor and Bob Rogan in one camp, Trippi in another, and everyone else in a third.

The result was that internal decision-making processes tended to be chaotic, with top supporters getting contradictory marching orders from Trippi and the Burlington staff in the same day.

"We couldn't get answers on simple things," said one, who asked to remain anonymous. "It just seemed like there was no coordination between Trippi, the fundraising machine and the governor's closest aides from Vermont. I guess that turned out to be the case."

But none of that mattered in the fall, when the Dean campaign could seemingly do no wrong. The media was writing process story after process story about the brilliance of the movement and Trippi, its tech-savvy orchestrator. After all, it was hard to argue with the enthusiastic crowds who flocked to campaign events, the estimated $40 million the campaign raised over the Internet, and the resultant lead compiled by Dean in the polls.

While Dean fought fierce opposition from moderates in the Democratic Party and from Kerry and Dick Gephardt on the campaign trail, he won an avalanche of high-profile endorsements from politicians such as Al Gore and Bill Bradley and from activist celebrities like Rob Reiner and "Acting President" Martin Sheen, star of the popular "West Wing" television series.

By early January, Dean's strategy was clear: The campaign would overwhelm all contenders in Iowa and New Hampshire, making clear that opposition was futile. But a series of inopportune comments and outright gaffes fueled questions about whether an antiwar candidate with no foreign policy experience could defeat President George W. Bush. And in Iowa, voters repeatedly suggested that they found the candidate arrogant.

After finishing a distant second in New Hampshire this week, the campaign's spin was that Dean was making a comeback. But that was called into question -- sharply, and unexpectedly -- on Wednesday.

According to staffers, Dean held a meeting with campaign workers in which he announced that there was no money to pay staff at the beginning of February. He said that the campaign had $3 million in the bank, but that it had also racked up $3 million in debt that needed to be paid off. A senior aide confirmed the meeting, but not the numbers in question.

Even before the Iowa caucus, the Dean campaign spent aggressively in states with later contests in order to drive home the advantage of being the only "national" campaign. In Iowa, the campaign spent millions on advertising and on a massive organization of paid staff and volunteers in custom, bright-orange watch caps. But that spending did more to attract press attention than actual caucus-goers, and Dean finished third. And in New Hampshire, Dean outspent his closest rival by hundreds of thousands of dollars to air an ad blitz that helped to reverse damage to his campaign from Iowa.

"[Money] has nothing to do with the management changes at all," Dean said on an evening conference call with reporters.

According to some campaign sources, it was a change that Dean had contemplated since the Iowa loss, if not before. But it came to a head this week. "I think the governor just kind of had it with losing," said one campaign source who asked to remain anonymous. "He was itching to make a move, but he made a very good call post Iowa to stand pat. It was just time."

Whatever his ultimate reasons, Dean had seen enough, and decided to bring in Neel. Trippi, upon hearing the news, handed in his resignation Wednesday and left.

On Wednesday night, Dean said Neel was brought in to be a "centralizing" force in the campaign. Others suggested the appointment is meant to impose discipline on the reeling campaign, and, just as importantly, the appearance of discipline. Neel is a close friend of Gore's and a longtime aide; he was also a central figure during the 2000 campaign. But while Neel's lobbyist background only confirmed Gore's image as a Washington insider to those who wanted change, his corporate leanings are unlikely to harm Dean's outsider credentials -- and may even bolster his campaign with centrists.

Clearly, though, the timing is less than ideal.

When Kerry's campaign seemed moribund in November -- he overhauled his staff and attracted a ream of critical coverage. But Trippi's departure comes just a week before a series of contests in which Dean must either win something or risk going into free-fall.

At such a crucial juncture, it's not clear whether Trippi's departure will dent the seemingly infinite enthusiasm of the legions of "Deaniacs" who propelled him to the front of the field in 2003. Trippi, a veteran political consultant who came to the Dean campaign from a private-sector job with an Internet company, was the visionary behind DeanforAmerica.com, and was something of a hero to many of those supporters.

Shortly after news of Trippi's departure broke, "Brad in Mass" posted this comment on Dean's Blog for America: "Man. This is genuinely, truly harsh. I really, truly do not want you to go, Joe."

The danger is also that supporters loyal to Trippi will come to see him as a scapegoat, as some strategists clearly believe him to be. "I guess it was Joe Trippi who told Dean to act hysterical and say dumb things every day," Wolfson said sarcastically. "If there was ever a situation where a candidate should have fired himself, it was this one."

But Dean expressed no hostility for his former campaign guru. Instead, he said he regrets Trippi's decision, and hopes to convince him to come back and work for the campaign "after he's thought it through."

Trippi, for his part, also sought a graceful exit. "Howard Dean is the guy who is going to fight for the country for real change and [I] hope people stick with him," Trippi said as he left campaign headquarters with his wife, Kathy Lash, who also worked for Dean.

"I'm out of the campaign, but I'm not out of the fight," he said in an account reported by the Associated Press. "We need to change America."

Can Dean recover? Maybe. Even without Trippi, he has a core of supporters that will never abandon him. And while the other campaigns will be fighting each other all over the country in the Feb. 3 states, the Dean camp will hope to rebound by focusing on and winning delegate-rich states like Michigan and Washington on Feb. 7. As John Kerry can attest, comebacks have been built on less.

On the conference call, Dean discussed the strategy of patience. "It's going to be a long, long war of attrition, and we're preparing for that," he said.

But it's an untested theory, and time is running out.

Laura McClure contributed to this report.

Shares