"How do you get AIDS?"

"Do people get cranky when they eat drugs?"

"Is it normal for one breast to be bigger than the other?"

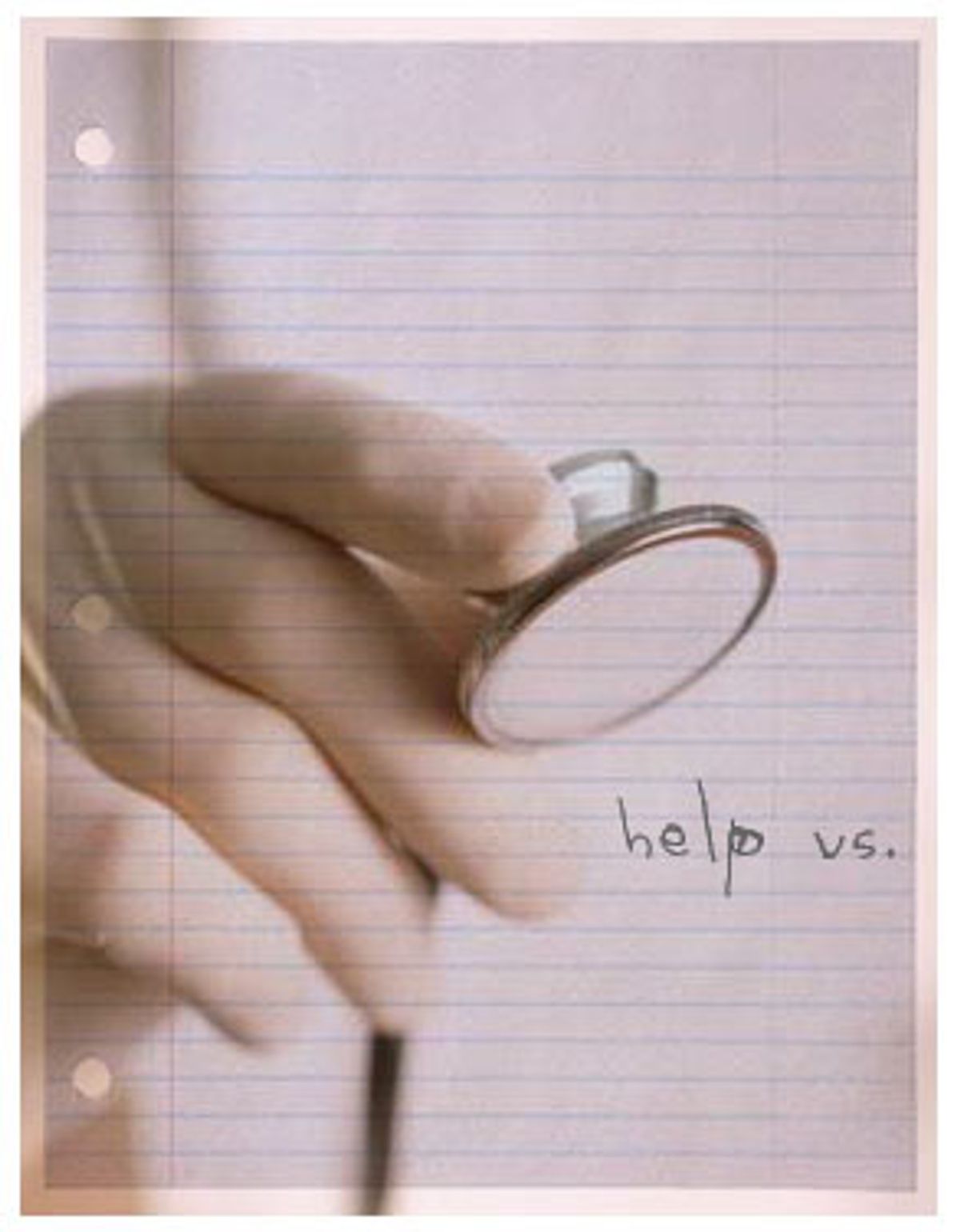

These are some of the anonymous questions -- printed on index cards and dropped in a Manila envelope tacked to my office door -- that I have received this month.

I work as a nurse in two San Francisco elementary schools, where many of my students, ages 5 to 11, face problems more complex than adding fractions or writing in cursive. A few are hungry; some are homeless; some are here illegally. All too many have parents who must work two or even three jobs.

When I was growing up in Boston, in the 1960s and '70s, the school nurse was a uniformed woman who lived in a peaceful little office near the gym. I visited her once with a stomachache and vaguely recall a white room with a pristine cot and a scale. She was there all day, every day, for whatever was needed. That era has passed forever. Today, in San Francisco, I am considered fortunate to have only two elementary schools and about 800 students; some of my colleagues have many more. In some school districts nurses travel to as many as seven schools, each with hundreds of students. And there's much more to do now than give out Band-Aids. Families are fragile. With work hours and commutes increasing, many of my students are in school from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. every day. I know a few who wake as early as 4 a.m. so that their parents can make it to their shift.

One of my schools draws from a nearby housing project, where Marcus, a first-grader, has already witnessed four shootings, the first at his preschool. Exposure to violence has left him tense and angry. He sits in class and glares, unable to focus on reading and counting, although his teachers know him to be extremely bright. Down the hall, his sister, who is reluctant to leave the house except for school, which she adores, hides her face and sucks her thumb. Still, for the most part, the children are surprisingly resilient and cheerful. Brianna, a tiny first-grader with golden shoes and a thousand braids, grabs at my stethoscope every time she sees me to hear her heart "beeping." Jason, an 8-year-old who is anxious about the complexity of third-grade social maneuvers, sends me notes through his teacher, addressed to "Dr. Lisa," giving me updates on his day. And Minerva, an angel-faced 9-year-old, and self-described "drama queen," regularly shows up just to chat because, as she puts it, with her winning smile, "I have issues."

The families are also resilient and cheerful: showing up in the rain to applaud the Halloween costume parade that marches around the block; snapping photos at the fifth grade graduation; picking up and dropping off each other's kids; spending hours in the evening listening to their children reading aloud and holding flashcards.

I have been a nurse for 11 years, and this assignment is the most compelling and challenging of my career. I started working in the schools on Halloween of 2002. Quickly, I became swept up into 60-hour weeks of finding emergency mental healthcare for the 8-year-old who says she wants to kill herself; teaching 50 first-graders how to brush their teeth and when to wash their hands; assuring teachers that while lice are a nuisance they are by no means fatal; and tracking down someone to bring in a child's asthma inhaler when all of the phone numbers on his emergency card have been disconnected.

"Why do we pee?"

"What do bones look like?"

"If you eat unhealthy food what will happen to you?"

As San Francisco becomes increasingly unaffordable, more children are commuting an hour or longer from less-expensive outlying cities or are boarding with grandparents in town. Many lack health insurance and depend on urgent-care clinics or emergency rooms. Increasing numbers of students come to school with chronic conditions, such as asthma and obesity. Some are not allowed to play outside their homes because it isn't safe.

The image of traveling school nurses bewilders people from my generation or my parents'. At a recent gathering, I described one of my schools to another nurse, an extremely competent woman in her 50s, with decades of patient care experience.

"Are you the only nurse at that school?" she said.

"I'm the only nurse at both my schools," I replied.

"God," she said, refilling her glass, "that sounds stressful."

Being split between schools is a bit disorienting. When Ryan comes in complaining of a stomachache I have no idea whether he shows up every day with the same ailment. Sometimes I ask the secretaries whether a student is a "frequent flier," but they are not always certain themselves. Out of necessity, sick students get squeezed into the office bustle, tucked among phone calls, discipline problems and UPS deliveries. I rarely hear about what happens on days I'm not there, except from the kids themselves, who might run up on the playground and reproachfully inform me: "I threw up yesterday and you weren't there."

Why do people catch asthma?

What are the bumps on your tongue for?

"Why are boys attracted to girls and vice versa?"

Unlike hospitals, where I worked for many years, schools have few available diagnostic or therapeutic tools. Accustomed to intravenous solutions, radiology departments and nice, clear physician orders, I was initially indecisive when students showed up with headaches, weird rashes, bumps on the head. Was Alicia's stomachache bad enough to warrant a phone call home (waking up Mom, who had just come off night shift), or would 10 minutes with a hot-water bottle and some crayons do it? What about Gustavo, the lonely new boy who fell down the stairs and then claimed he couldn't open his eyes? Most troubling, what should be done with 5-year-old Justin, who -- feverish, coughing, miserable -- burst into hysterical tears when I prepared to call his mother and cried, "I don't want to go home!"

The job consists of constant judgment calls and I'm slowly acquiring a few tricks. I have learned, for instance, that some children simply need occasional breaks from class. Last week, 8-year-old DeShawn appeared at my door with a headache. I handed him a jigsaw puzzle and he settled down on the floor while I resumed my paperwork. It was perhaps 10 minutes before he rose and told me, "My headache's better," and dashed back to class. Splinting injured fingers with adhesive tape is also surprisingly effective. And, at least for kindergarteners, there seem to be few ills that cannot be remedied -- if not cured -- by stickers.

When I described the job to my parents, what my father found most puzzling was my statement, "I'm not really supposed to do first aid." Like most of us, he has an image of the school nurse as someone mopping up blood, soothing stomachaches, applying Band-Aids and ice.

"So what do you do?" he asked me.

It was surprisingly difficult to explain. I have a six-page job description that discusses interdisciplinary team meetings about problem kids, the school crisis response team, classroom health lessons, faculty in-services, and PTA meetings. I have an administration-created to-do list that mandates -- among a hundred other things -- snagging a space with a desk and a phone (also surprisingly difficult); publishing a monthly newsletter for parents about lice, nutrition, dental care, etc.; teaching puberty lessons for fifth graders; and ensuring that there is a legal and safe system for administering medications at school.

The job sometimes seems impossible, unmanageable, constantly spiraling out of control. I ricochet among the various responsibilities and needs, never quite doing enough. One month I'll teach lots of health lessons, bringing intestines, bones or stethoscopes into classrooms. Then I'll spend time calling parents whose children aren't current on their immunizations. At any one time I have 50 items on my list. Out of the 300 or 400 students at each school, there are 20 or 30 who show up regularly and make themselves known. In the meantime, of course, I get pulled in to first aid, and -- although my department keeps telling me that we're not there for that; that the secretaries do it on the days we're not there, anyway -- it seems unnatural and downright churlish to refuse. Besides, so much of what I do is social work, case management and teaching -- disciplines in which I have not been trained or licensed. It's a relief to occasionally do some actual nursing.

Can African-Americans get head lice?

Why do we have teeth?

If you eat nothing but junk food, will you die?

Often, I'm uncertain whether I'm making an impact at my schools. I know the kids enjoy rubbing Glitterbug cream on their hands (a potion that glows under a black light to indicate how well you have washed) and trying out my stethoscope. But Javier still falls asleep in class and Angelina just can't seem to retain her letter sounds, even though her mother practices nightly with her.

Still, last month a kindergartener pointed me out to his mother in the hallway: "She brought the real lungs to our class." The mother stopped me and recounted how her son had come home and described the two sets of lungs I had lugged over in heavy Tupperware: healthy lungs and lungs blackened from decades of smoking. "I knew all that," she said, "but somehow hearing it from my son was different." She had stopped smoking that week.

Several weeks ago, after a day at school spent putting out one small fire after another -- tantrums, fights, students running away from the school, children falling (or pushing each other) off the monkey bars -- without crossing a single item off my list, I indulged in a fantasy about a quiet office job, just me and a stack of papers and only one place to be that week.

Before I left that afternoon, I reached into the Manila envelope on my door, as usual, to take the week's questions home to type up.

"Can you bring back the lungs?"

"What are we doing in health club next week?"

"Where do babies come from?"

At the bottom was a card that made me decide to hold off on the office job, at least for now. There was no question on it, just the words:

"Help us."

Shares