About a mile and half from the house I live in, past a high-walled compound occupied by the Constitutional Monarchy Movement party, past the home of a member of the Iraqi Governing Council where a loitering American tank often indicates the presence of high-level visitors, past a row of convenience-store-type shops where I often stock up on the Nestle brand bottled water that I drink by the gallon each day, past the intersection where my driver swears that the women we see lingering in long skirts and hijabs are prostitutes, past the massive skewed ziggurat Babylon Hotel building where wedding parties daily wreak havoc with the traffic by double-parking cars and buses, past a long mercantile block with a bakery, butcher, furniture-maker, and several competing vegetable stands, sits the entrance to the 14th of July Bridge -- one of several bridges that spans the muddy Tigris River which meanderingly bisects the city of Baghdad.

The bridge, named for the day of the 1958 military coup in Iraq that ousted the monarchy of King Faisal II, is one entry point into Baghdad's now infamous "Green Zone," the place where the Coalition Provisional Authority, hunkered down behind a multimile diameter of concrete barriers and military checkpoints, runs this country. Inside this city within a city is one of the strangest Oz-type landscapes I've ever seen. Titanic palaces sit half-chewed and slumping from the war's bombing campaign. There are empty lots where crows watch over ruined military vehicle parts and peck around on the winter-wet ground. Subdivisions (called "camps") of prefab trailers act as home to American subcontractors doing big business here -- Bechtel, Bearing Point, and Kellogg, Brown & Root. There's a convention center containing the main USAID office and other offices, as well as the small theater where proconsul Paul Bremer and allied forces military commander Lt. Gen. Ricardo Sanchez hold those press conferences you see on TV all the time. Military camps, CPA and military mess halls rub shoulders with collapsed palaces, a state-of-the art military hospital, some gyms, and the Al-Rasheed hotel -- still mostly empty following the RPG attack last October that killed a colonel and left 18 soldiers and CPA employees wounded. Full parking lots stand next to abandoned office buildings and the Saddam-commissioned "Tomb of the Unknown Soldier," which, at first glance, I mistook for a soccer stadium.

In one corner of the vast enclosure sits a large neighborhood of Iraqi homes and apartment buildings, unwillingly annexed into the Green Zone due to its proximity to the American headquarters. This neighborhood lies just over the 14th of July Bridge and is as isolated from the rest of Baghdad as the American-occupied parts of the zone. In October, during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, the Americans shrunk the Green Zone perimeter and opened the 14th of July Bridge to general traffic, enabling Iraqis who live in the neighborhood to come and go as they pleased. But soon after, due to security concerns, the military shut the bridge again. Now, in order to use the bridge, Iraqi residents of the neighborhood must show a special pass and endure a long security check. For those traveling by car, this means waiting anywhere from 30 minutes to four hours in a line that backs up along Karada Street.

The other day, I took a fast taxi ride with my translator, Amjad, to the 14th of July Bridge. We got dropped off in front of an American tank that acts as the bridge's first line of defense. A few yards further, on the pedestrian walkway, we stopped to show I.D. (an American passport and press badge for me, a CPA-authorized badge for Amjad) to a combination of American and Iraqi soldiers. They patted Amjad for weapons and checked out the contents of my backpack and let us continue.

We walked across the bridge under a dark mica sky and paused at a large empty intersection on the far side of the bridge. The main CPA gate is miles away, right next to the convention center, so Americans don't have reason to come to this part of the Green Zone much. A few cars with Iraqis -- residents of the nearby neighborhood -- passed us, then a stubby convoy of Army trucks. On the sidewalk, an Iraqi woman, her three teenage daughters and a small boy hustled toward us on their way to the bridge. Two of the girls, wearing long skirts, hijabs and light-blue eye shadow, held the handles of an empty duffel bag that they swung between them as they walked.

Amjad flagged the family down and asked whether they lived in the Green Zone. They did, but they were in a hurry. They needed to cross the bridge, walk to some shops and return (past the security with its requisite check of their parcels) before either the dark or the rain caught up to them. So we accompanied them for a few minutes, back toward the bridge, while they told us a little about their situation.

They were part of a family of 12 living in one of the apartment buildings we could see poking at the sky a few blocks away. They lived on the seventh floor in a four-room apartment. Like a lot of neighborhoods in Baghdad, they had power for two hours on and two hours off. These power outages don't affect the American portions of the Green Zone where high-voltage generators ensure 24-hour electricity. When the power went out in the family's apartment building, the water went out, too, meaning a seven-flight trip to use the bathroom or fetch buckets of water for cooking and cleaning. The elevators in the building didn't work at all. The family had chipped in to pay 10,000 dinars to have them fixed but that was weeks ago and nothing had changed. Complaints to the Americans did nothing, they said.

I asked whether they saw many Americans or interacted with them. They said no. This is not a surprise in greater Baghdad: For many of the Iraqis I meet, I am the first American they've ever spoken to. But it seems strange for five people, locked by circumstance behind the Green Zone walls, to have so little contact with their inadvertent neighbors.

The girls became impatient to get over the bridge so we said goodbye. Before we parted, I asked them their family name but they shook their head in response. They didn't want to give their name. Didn't want to get in trouble for complaining about the Americans. They used to have Saddam as their neighbor. Now it's the Americans, occupying his old digs, that perpetuate their wariness.

A few minutes later, Amjad and I met up with five middle-aged women walking in a clutch toward the bridge. All five worked in the Bechtel camp -- four as cleaning staff and one as a cook. They kindly stopped to talk with us and we stood on the sidewalk in the deepening gray while a flock of lost seagulls flew corkscrews overhead. All five lived outside the Green Zone and were on their way home from work. On the other side of the bridge, they would use taxicabs to take them the rest of the way home. Cab rides to and from work were expensive, they said, but they had no other options. One woman, terribly skinny and holding a napkin over her mouth to block the worst bite of the cold air, told me she lived in the Jedida neighborhood, which takes half an hour to an hour to get to in a cab, depending on the traffic.

All in all, the women felt very happy to have their jobs, though. Most supported their whole families with the money they made. "The men are sitting in the house," one woman said, "and we are working. I wish you could find work for them!" It was their impression that Iraqi women have an easier time getting work in the Green Zone. Many of the service jobs there (for instance, staffing in the enormous Kellogg, Brown & Root mess halls where soldiers and CPA employees eat all their meals) were filled right after the war by imported workers from Pakistan and the Philippines. These guys sign one-year contracts, get flown to Baghdad, and live in their own small compound within the Green Zone. They get paid wages that are relatively high compared to what they can make at home (although low by U.S. standards), and they don't pose any of the security threats that Iraqis potentially do.

The women I met had been hired by a company whose name they couldn't remember -- a Bechtel subcontractor. Not knowing the name of your employer would be strange in the U.S. but doesn't seem at all weird here. Iraq has no checking system right now, and thus no traditional payroll system. The women get paid in cash each week from a company representative and probably haven't heard their company name uttered in months. The cook -- a bubbly woman with a streaked bob -- found her job first, then she brought in her friends. She said that was the way it works, "like a chain." I asked whether she or any of the women had been questioned about their background or undergone a security check. They all shook their head. "No," they said. "No."

Lately, though the women are still very grateful for their jobs, they feel worried. All but the cook hide the fact that they are working for the Americans. Only their closest family members know. It's just too dangerous these days. I asked whether the women knew anyone who had been assaulted for working with the Americans. One of the women, who was short and round and had been swaying from foot to foot to stay warm, said, "Not personally. You hear stories. The women outside the military base ..."

She was referring to the nine women whose minibus was attacked as they were on their way to their jobs in the laundry of the Habbaniyah American military base west of Baghdad. Four of the women were killed, others badly wounded. Working with the Americans in any capacity here in Iraq has become a hazardous job. Perhaps because of these fears, perhaps because they didn't want to get in trouble at work, all five of the women declined to tell me their names before continuing on their way.

Amjad and I continued down the empty boulevard. Next to the sidewalk, a long curtain of vibrant blue plastic sheeting blocked the view of an abutting lot. Further down the road the sheeting had flopped from its tacking and I looked through the gap at a junk-littered field. In the middle of the field was what looked like a small party tent -- the kind that brides and grooms rent in case of rain. I have no idea why it was there.

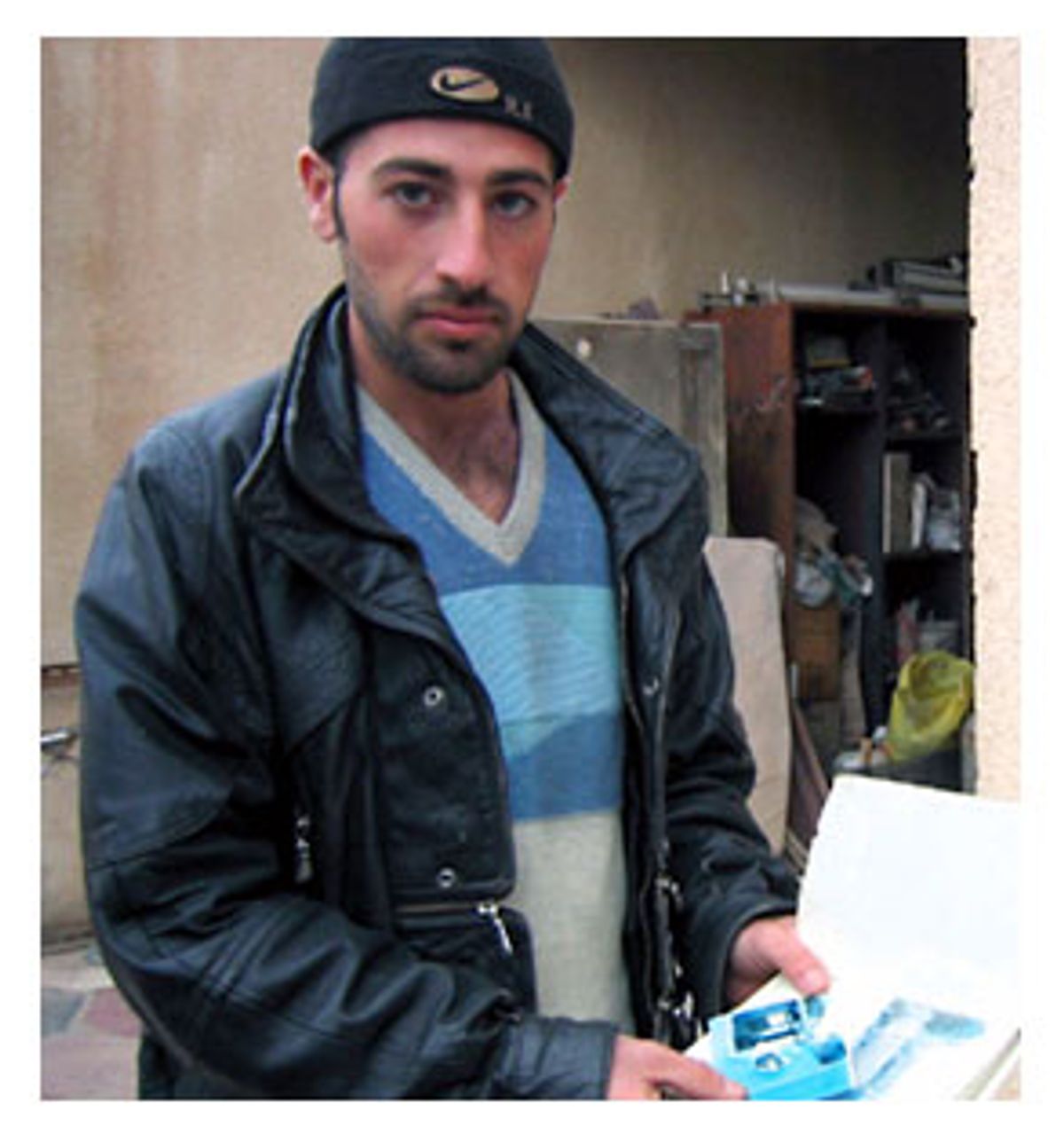

We met Sian, a college student in computer sciences, who sat in a red plastic chair doing his homework and watching over his friend's sidewalk soda stand. It wasn't much of a stand: a half-case of Seven-Up and (unaccountably) three plastic jugs of car lubricant. Sian has lived all his life in the neighborhood. As we talked about what it meant to have been annexed into the American-secured Green Zone, his friends drove up and joined us. One, Ivan, wore only jeans and a T-shirt compared to Sian's heavy leather multizippered jacket and wool Nike cap. The third friend stood back and listened and I never learned his name.

Sian and Ivan both felt pretty pissed off about living in the Green Zone. As students, they needed to leave it almost every day. If they took their car, the drive home could be hours. "College is from 8 to 2 p.m.," Ivan said. "From 2 to 6 we're at the checkpoint. How can I read? How can I do homework?" Timewise, other gates are even worse, he said -- once he sat in line for 10 hours.

When they do finally get to the front of the car line, the bomb-sniffing dog gets in and leaves muddy paw prints on the car seats, they told me. It snuffles any food they might have. They have to stand on the sidewalk during the car search. Soldiers yell at them if they stand with their hands in their pockets. Americans would cut to the front of the line. When Ivan complained once, he got sent all the way to the back. But if they don't take their own car, they have to pay for taxi trips between the bridge and school. It's part of the reason they sell the sodas. To pay for taxi trips.

Sian told me that his family feels very isolated. Relatives can't visit; they don't have the proper identification. "In the past circumstance," said Sian, "this area was dangerous ..." He raised his eyebrows to clarify that fact that he was talking about Saddam. It's a facial conveyor many Iraqis still use -- mostly out of habit, I think -- rather than utter the name of the dictator out loud. "But," he continued, "we had a social life."

Often, when speaking to Iraqis, the American invasion of their country seems like ancient history. It's the present occupation, and life under it, that consumes the people I meet. They've stopped questioning whether the war was just. All they want to know is when they'll have power, jobs, safety, potable water, no gas lines, easy access to their homes. The debate over quality of life (and why it mostly sucks these days) has eclipsed political debates for most Iraqis.

As we stood and talked, some friends from the neighborhood drove up and a short discussion about power (an Iraqi word I know very well since everyone is always telling me they don't have it) ensued. When the neighbors drove away, Ivan explained that his house had been without power for five days, but had just come back on. He pointed down a dirt side street nearby. "The whole block," he said, "no power." No one knew why. A row of squat middle-class houses occupied one side of the little road. Across from them was an empty lot filled with some garbage and a gleaming white speedboat, marooned and tilted onto one side of its belly.

Sian began telling me about his family's house -- how it had been hit by RPGs during the war and nearly destroyed in the ensuing fire. He asked whether I wanted to see, so Amjad and Ivan and Sian and I drove to Sian's house nearby. His house is a block or so away from the depressing and decrepit-looking apartment buildings where the family I met earlier in the day live. Mud from recent rain filled big potholes in the streets, kids ran around barefoot, a guard patrolled with a Kalashnikov. The dark sky made the neighborhood seem much dirtier than it actually was.

At Sian's house we piled out of the car and he opened a gate to the low retaining wall that enclosed a small front yard. Winter-weary rose bushes circled the yard and the family guard dog barked at us from the end of his rope next to the wall. Soot stains crept up the front of the box-shaped house, interrupted by large pockmarks, made by the RPG attack. Sian and his family hadn't been in the house at the time. Their whole neighborhood had been evacuated in anticipation of the war. As far as he knew, U.S. soldiers had attacked the house because they suspected Iraqi soldiers were hiding inside.

Sian lead us into the house and went to fetch a plastic photo album that contained pictures of the original damage. He flipped though to show me the aftermath of the fire. The house's interior had been completely charred and the furniture destroyed. We stood in the house's dim interior (power was out) and he proudly pointed to the work his family had done. They had cleared the interior and repainted the walls gleaming white. "We haven't done the doors yet," he said, almost apologetically. All the doors remained black with soot, though a ghost of yellow paint could be seen in some place, indicating their original color.

The family had moved back in while working on the house. They had no other place to live. Relatives had lent them some furniture -- a greenish-brown living room set, a dining table. In Sian's bedroom, his clothes lay in a stack against the wall waiting for an eventual dresser.

The smell of the paint mixed with the lingering smell of smoke left me lightheaded and after a proper tour, we went back outside. The rest of Sian's family arrived then -- his parents and younger sister. His father repeated the story Sian had told me. The RPGs, the fire, the work they had done to fix the house. He used all his savings to fix it and borrowed some money as well. "I'm tired," he said. "I have only this house. I built it myself, block by block in 1968."

Sian's father went to the CPA to try to get some money for the house. "I thought the Americans might have the power to compensate me," he said. "What shall I do? I created the war? I didn't. I just want to have a roof with my family." I stood and listened while Sian's father talked through his frustration. His family loosely ringed him, looking slightly embarrassed but nodding in agreement, also. He asked me whether the Americans would eventually repay him for the damage. "I think they have this policy," I said, "you see if it happened during the war ..." I couldn't bring myself to say what I knew to be a fact: The U.S. does not pay for war damage. Even if you're living right there in the Green Zone, beneath their leaden protective wing. They won't pay Iraqis on claims pertaining to the period of war. And, as we all know, that war ended in "mission accomplished" a long time ago.

Shares