There’s something both maddening and exhilarating about watching movies that come from nations without thriving film industries: It’s maddening because we often feel we should approach these pictures with reverence and awe, lest we be branded as closed-minded Westerners who don’t have the patience to sit through interminable and repeated shots of, say, pots of milk being stirred by wrinkled old men. At the same time, it’s exhilarating to feel a connection to a culture you don’t know, and to recognize that the people who really want to make movies will find a way to do it.

Afghan director Siddiq Barmak’s “Osama,” set in the era of Taliban rule, tells the story of an Afghan girl who, at the risk of being discovered and killed, masquerades as a boy in order to earn money for her family — a necessity since her father and uncle have both been killed and it’s forbidden for women, even widows, to work. It’s impossible not to respond to the girl’s plight (she’s the Osama of the title) or to that of the women around her: A peaceful demonstration of burqa-clad widows, arguing reasonably and meekly for their right to support their children, is squelched, violently, by Taliban thugs. Men and even young boys strut through the streets like dusty roosters — their sex has automatically made them kings — while women aren’t even allowed out of the house unless escorted by a male relative. Even if we accept, as we need to, that fictional films (even those inspired by a true story, as this one was) by their very nature trade on dramatization and exaggeration, everything in “Osama” rings true, jibes with what we’ve seen or read about the Taliban in the news.

The truths “Osama” tells don’t automatically make it a great picture. In fact, the big problem with “Osama” is that it too often feels instructional — it has a “listen up, people!” vibe that distracts us from, instead of drawing us into, the humanity of the characters. But “Osama” is at times very compelling, simply because Barmak has cut us a window into a world that hasn’t yet been portrayed on the screen in quite this way.

Afghanistan has virtually no film culture or industry to speak of. According to the movie’s press notes, because of cultural and economic limitations, the country has produced fewer than 40 short and feature-length films over the past 100 years. (For comparison, consider that India produces three films per day.) “Osama” also has the distinction of being the first feature film to be made in Afghanistan since the fall of the Taliban (or, obviously, its rise). Barmak, who learned filmmaking at Moscow University in the late 1980s, was head of the Afghan Film Organization from 1992 to 1996, when the Taliban’s ascendancy forced him into exile in Pakistan. Barmak returned to Afghanistan after the Taliban’s fall. He was able to complete “Osama,” his first full-length film, with help (including materials, equipment and lab services) from Iran’s Ministry of Culture, among other organizations.

With that back story, “Osama” is surely the little movie that could. (It recently won the Golden Globe for best foreign picture.) Since an Afghan film is such a rarity, as moviegoers our first inclination is probably to grade on the curve: After all, even though no viewer or critic wants to come out and say, “For a movie from Afghanistan, ‘Osama’ is pretty good,” that may be what many are secretly thinking.

On the other hand, it’s inherently condescending to heap praise on a quiet, modest movie simply for its “otherness.” Maybe it’s healthier just to come out and say it: For a movie from a country with a very slender film culture, “Osama” is pretty good. Barmak has a vivid cinematic sense: He knows how to stage quietly dramatic sequences, as when a group of women gather to celebrate the impending marriage of one of their own. They sing and play tambourines, until they get word that the Taliban police are headed their way. Then they pull their burqas over their heads and turn their party into a funeral, chanting and moaning. It’s a potent way of making the point that these women could die simply because they had the audacity to throw a party. And it’s effective simply because movie audiences always respond to ordinary people who find clever ways to outwit authority.

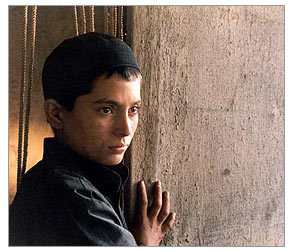

Barmak’s compositions are often striking, particularly a sequence in which we watch the terrified Osama, urged by a bunch of aggressive little boys to prove her “masculinity,” tentatively climb a tree — she clings to its lonely, pointed branches, which are outlined starkly against the sky. The young actress who plays Osama, Marina Golbahari (Barmak discovered her on the street), has a searchingly open face, and Barmak’s camera captures both its beauty and its stirring innocence. There isn’t a moment in “Osama” when we don’t fear for its young protagonist, and those fears are justified, given the cruelties that befall her — they pile on one after the other, with no relief.

“Osama” is probably a pretty accurate reflection of the horrors suffered by women under the Taliban. But by the end of the movie, you feel as if you’ve been worked over. An effective picture can send you home feeling bereft and devastated. But that’s different from feeling that the life has been beaten out of you. “Osama” leaves you with nothing. That’s not to say Barmak should have gone with a falsely optimistic ending. But movie audiences need a little bit of life to cling to, even in a tragedy. That’s what distinguishes a dramatic work from a tract.

Barmak cites Andrei Tarkovsky and Abbas Kiarostami among his influences, which should give you a sense of his movie’s pacing: In other words, “Osama” is leisurely, and you can expect a fair amount of pot stirring. Those influences come to the fore in other ways: There’s a stately artfulness to “Osama” that keeps it from being wholly affecting. But “Osama” did leave me wondering what else Barmak is capable of doing. And I think it’s impossible to watch the movie without feeling at least a glimmer of defiance. Afghanistan should make more movies — simply because now it can.