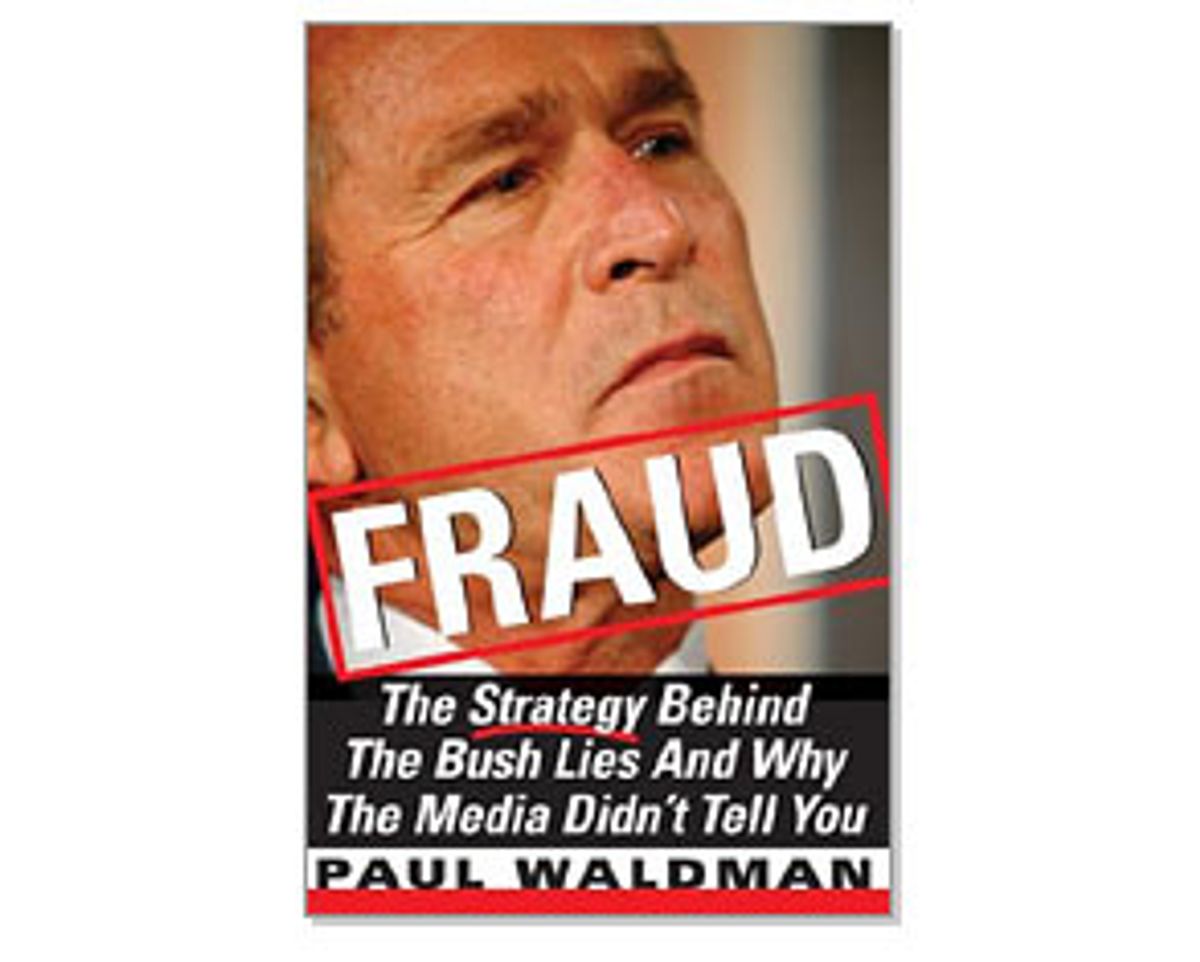

Before a press conference in August 2002 at the Bush estate in Crawford, Texas, workers brought in hay bales to cover up the propane tanks sitting in camera view, the better to give the impression that the president was a real old-time rancher. Of course, Bush had purchased the spread just before the 2000 campaign. The hay-bale tableau was in many ways a perfect metaphor for the persona of George W. Bush himself: Artifice intended not only to conceal reality, but to give the impression that Bush is "real," a simulation of authenticity itself.

The popular perception is that George W. Bush is just a "regular guy" -- unpretentious, friendly, likes country music and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, not some highfalutin know-it-all who thinks he's better 'n other folks. But this image is a persona, carefully constructed over the years to deal with one of the key difficulties facing members of the Bush dynasty. After all, we are talking about a man afforded advantages available to literally but a few dozen Americans, who walked on a path paved with the priceless cobblestones of influence and wealth, who earned so little in life but was given so much. Given that Bush's father was defeated in 1992 in large part because of his perceived inability to understand the struggles of ordinary people, the son's advisers understood that a man with George W.'s particular combination of experience and skills could hardly be presented to the public as a model of empathy. So as the scion of the Bush dynasty was prepared for his entry into public life, he was burnished with a down-home gloss and a new man was created. The creation of this persona came off virtually without a hitch.

While some of the details may be phony and some may be false, the package comes off very convincingly. And the continuing success of Bush's regular-guy routine is what makes it less likely that reporters will question its veracity. Though they strike a cynical pose, assuming that all politics is artifice, nothing yields higher praise than an image successfully constructed. "Just as TV decries photo-opportunity and sound-bite campaigning yet builds the news around them," wrote communication scholar Daniel Hallin, "so it decries the culture of the campaign consultant, with its emphasis on technique over substance, yet adopts that culture as its own." The candidate who falls off a stage (as Bob Dole did during the 1996 campaign) or holds a press conference with improper lighting will become the object of scorn, while the one who performs in a flawless photo-op will find reporters praising the skill of his operation.

Among the consequences is that reporters will often ignore real evidence about public opinion in favor of their gut feelings about how image-making is received. It is commonly accepted and reported, for instance, that Ronald Reagan was a spectacularly popular president who basked in the warm glow of Americans' affections for eight years. But when stacked up against other presidents, Reagan's popularity was decidedly mediocre. He averaged an approval rating of 52 percent over the course of his presidency -- better than Carter, Ford, Nixon and Truman but worse than Clinton, George H.W. Bush, Johnson, Kennedy and Eisenhower. Reagan's best approval of 68 percent was bested at some point by every president since polling began under Roosevelt, with the exception of Nixon. Nonetheless, the myth of Reagan's popularity persists to this day.

As Michael Schudson and Elliot King argued some years ago in a piece titled "The Myth of Ronald Reagan's Popularity," the idea took hold in no small part because Reagan's handlers were so adept at the staging of public events, and reporters -- perhaps believing that ordinary people are rubes easily persuaded by pretty pictures -- concluded that because the events impressed them, they must have impressed the American people as well. George W. Bush's people are, if anything, even more skillful. Michael Deaver, the Reagan adviser revered as the Michelangelo of presidential photo-ops, said in admiration, "They understand the visual as well as anybody ever has ... they've taken it to an art form."

Much as they did with Reagan, the current press corps assumes that the public is invariably swayed by the Bush photo-ops even when there is no evidence to support that conclusion. In the most celebrated case, the media gave enormous coverage to Bush's landing on the aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln, and praised its success in gathering the public behind Bush's declaration of victory in Iraq. But for all the attention given to his glorious landing, the event had no discernible effect on Bush's popularity -- zero. The last Gallup poll before the carrier landing showed Bush's approval rating at 70 percent; the first poll after the carrier landing showed his approval at 69 percent. Yet long after Bush's approval fell from its post-Sept. 11 highs, journalists continued to repeat that Bush was enormously popular.

The Character Issue

Watch George W. Bush give a speech, and you'll notice that something comes over him when the subject turns to war or executions. He leans forward, all hesitation gone from his voice, as he struggles to contain a smile and his eyes gleam with what can only be described as bloodlust.

So it shouldn't have been a surprise that as the war with Iraq approached, Bush became increasingly excited. According to the Washington Post, friends and lawmakers who met with Bush just before he launched the invasion found him "upbeat," "chatty," "cocky and relaxed" and "in high spirits." The most revealing moment came when he thought the cameras were off: Before he gave his national address announcing that the war had begun, a camera caught Bush pumping his fist, as though instead of initiating a war he had kicked a winning field goal or hit a home run. "Feels good," he said.

Yet the mainstream press, given this appalling glimpse into the president's character, chose to remain silent, no doubt hesitant to become the target of the White House's wrath, not to mention that of innumerable conservatives demanding that they support the president in a time of war. But after all, we are talking about what ABC News' "The Note" referred to as "inarguably the most beaten down press corps in the modern era."

Like Father, Like Son

Keeping his personality's ugly side under wraps is only one part of what is required to sustain the Bush persona. To appreciate its essence -- the regular-guy Texan -- you have to understand his father's struggles with his own image, the awkwardness with which the Connecticut preppy attempted to relate to ordinary people, particularly in his adopted state.

The elder Bush made two unsuccessful runs for the Senate, in 1964 and 1970, and both times he got out-Bubba'd, as his opponents convinced voters that Bush was insufficiently Texan, insufficiently Southern, insufficiently down-home, a fancy-pants carpetbagger who was trying to take over on behalf of the Eastern establishment. "Elect a Senator from Texas," said his 1964 opponent, Ralph Yarborough, "and not the Connecticut investment bankers." In 1970 Lloyd Bentsen said much the same thing. It worked, and Bush was beaten both times.

By the time he got to the national stage, George Sr. figured out that the key to dealing with his preppy question was not in convincing people that he wasn't one of the elite, but in redefining the elite itself, just as many conservatives had done before him. His attempts to disown his pedigree -- like proclaiming his love for pork rinds, an assertion greeted with universal guffaws -- fell flat. So he and his team decided to define their 1988 opponent Michael Dukakis, a self-made son of Greek immigrants, as a member of the "Harvard boutique." By the time Election Day came, Americans were sufficiently convinced that Dukakis wasn't one of them, and gave Bush Sr. the White House.

In the 1992 campaign, Bush renewed his attack, the son of a wealthy senator once more deriding an opponent born of poor parents for being part of the "elite," a word peppered throughout his attacks on Bill Clinton. By defining the American "elite" not as an economic one (which would put his family at its very center) but as a cultural or, more specifically, intellectual one, Bush sought to classify his opponents as not only alien from ordinary Americans, but as members of a class with power and influence.

George W. Bush understood well the preppy image his father carried and was eager to stake out a contrast to it. But when he made a premature run for Congress in 1978, George W.'s opponent, Kent Hance, did exactly the same thing Yarborough and Bentsen had done to his father, running radio ads mentioning where Bush went to high school, and deriding Bush for coming from Connecticut. Hance won with more than 53 percent of the vote.

It was the last time anyone would ever out-Bubba George W. Bush. So when he was asked as he was preparing to run for governor what the difference between him and his father was, Bush would say, "He went to Greenwich Country Day and I went to San Jacinto Junior High School in Midland." In other words, he was a Connecticut Yankee, but I'm a real Texan. In truth, Bush attended San Jacinto Junior High for one year, then went to an elite private school in Houston, followed by spending his high school years at Andover. Bush seldom misses an opportunity to reiterate that he is a real Texan, down to his habit of attributing ordinary American sayings to Texas, as though by speaking them he reveals his provincialism (he once described "show your cards" as "an old Texas expression").

As in many areas, George W. was far more successful in posing as an anti-elitist than his father. Whether George Sr. actually enjoyed pork rinds as he claimed, nobody believed for a second that his snack-food preference made him an ordinary Joe. But the son, with his love for baseball and plain speakin', managed to make most people forget his Brahmin pedigree.

The Liberal "Elite"

Although there may never have been a point in American history in which so much power was held by a party so singularly devoted to the interests of so few, Republicans continue to argue that they speak for the little guy. Of course, this strategy is not a new one; Aristotle noted that "all people receive favorably speeches spoken in their own character and by persons like themselves." It is all the easier to convince people that you are a person like themselves if you can convince them that your opponent is a person quite unlike themselves.

Just as Newt Gingrich once counseled that Democrats should be portrayed as "the enemy of normal Americans," Republicans, from President Bush on down, endlessly assert that only they and those who support them are real Americans. When he travels to the Midwest or South, Bush calls it a "Home to the Heartland Tour."

"Whenever I go home to the heartland," Bush says, "I am reminded of the values that build strong families, strong communities and strong character, the values that make our people unique." The implication, of course, is that the other parts of America are not so strong in those values -- and not so American. When Bush makes this argument, few are so rude as to point out that the man who claimed to be "a uniter, not a divider" has no hesitation in dividing us into the "real" Americans and the not-so-real. And when conservatives say this sort of thing, liberals usually run scared, afraid to stand up and defend what they know to be true, that no one part of America is more American than any other. People who live in Rhode Island or Oregon are no less American than people who live in Oklahoma or Kansas. Nothing about life in Boise is inherently more American than life in New York. No Democrat would dare to suggest that Omaha is not really part of America, but when the Democratic Party elected to hold its 2004 convention in Boston, House Majority Leader Dick Armey quipped, "If I were a Democrat, I suspect I'd feel a heck of a lot more comfortable in Boston than, say, America."

Bush unifies the various strains of the right's anti-"elite" ideology: The geographic argument, the argument about the alleged bias of the media, and the anti-intellectual argument. In 1953, Arthur Schlesinger Jr. wrote, "Anti-intellectualism has long been the anti-Semitism of the businessman," by which he meant that those at the top of the heap use intellectuals as a scapegoat to distract people from the societal inequities that actually affect their lives: those of wealth and power. Intellectuals are posited as both sinister and powerful, conspiratorially undermining the values of ordinary people.

In order to sustain a fear of intellectuals, the conservative media apparatus conducts a coordinated effort to elevate any perceived transgression by any liberal -- particularly one associated with education -- to the status of a major news event. So when one stupid professor in New Mexico says to his class on Sept. 11, 2001, "Anyone who can blow up the Pentagon has my vote," the incident receives a torrent of news coverage, spurred on by conservative talk radio, as though the speaker in question were someone of national importance. When the National Education Association puts up a Web site to help teachers find ways to discuss Sept. 11 with their students, the Washington Times writes an appallingly dishonest story distorting the NEA's suggestion to avoid scapegoating all American Muslims into an instruction to avoid blaming al-Qaida for the attacks; the false charge is then picked up by conservative commentators and columnists who push it onto editorial pages all over the country.

And it needn't only be professors -- even lowly college students can be manipulated into providing fodder for the right-wing spin machine. The polemicist David Horowitz, for example, is provided with a steady stream of conservative foundation money essentially to devise ways to outwit 19-year-olds. So Horowitz will attempt to place insulting ads in college newspapers -- arguing, for example, that African-Americans should be thankful for slavery -- and then, when some of the newspapers refuse to run the ads, pose as an aggrieved hero of the First Amendment.

The conservative media apparatus is an integrated system in which stories circulate between talk radio, conservative magazines and newspapers and the Fox News Channel, generating momentum and pushing their way into more mainstream news outlets. The most enthusiastic goal of this media machine is locating and publicizing foolish things said by liberals, no matter how obscure or inconsequential the speaker may be, to inspire mainstream contempt for liberals. The idea that the words of some random professor or student are more important than the actions of the country's leaders may be farcical, but by giving endless attention to these alleged outrages, conservatives sustain the image of liberals as powerful and elitist and conservatives as persecuted and victimized. Were they so inclined, liberals could no doubt find conservative citizens who say stupid things too. But no one is paying them to undertake the search.

When ordinary people, told endlessly to be suspicious if not contemptuous of those with too much education, hear people snicker at George W. Bush's inability to put together a grammatical sentence, they sympathize. Far from being damaging, jokes about the president's intelligence and ineloquence serve to distract from his status within the aristocracy, providing evidence that Bush is not one of the elite, indeed is scorned by them. Presidential elections are won and lost over a variety of factors, but which candidate seems the smartest is not one of them. When liberals make jokes about the bizarre tangle of words that sometimes emerges from Bush's mouth, he is only too pleased since it serves the end of separating him from the elite.

Just a Good Old Boy?

Politicians are fond of telling a story in which a wise person, usually a grandparent, tells the future leader that he can be anything he wants if only he puts his mind to it. Someone probably once spoke these words to a young George W. Perhaps it was his grandfather, the senator, or his father, the president. Like most wealthy patriarchs, they no doubt believed it, just as George believes he earned everything he ever got, including a baseball team, three oil companies, and an easy entry into Yale. During his unsuccessful run for Congress in 1978, Bush remarked to a fellow Republican, "I've got the greatest idea of how to raise money for the campaign. Have your mother send a letter to your family's Christmas card list. I just did and I got $350,000!" The notion that there might be something unusual about George and Barbara's Christmas list hadn't occurred to him.

Too much is often made of politicians' personal backgrounds and experiences; after all, the working man hardly ever had a better friend in the White House than the aristocratic Franklin Roosevelt or a greater antagonist than Ronald Reagan, who grew up in a family of modest means. And no president since Abraham Lincoln did more for African-Americans than Lyndon Johnson, who nonetheless retained the vulgar mannerisms of his Southern upbringing. But when we see how George W. Bush reacts to the interests and needs of ordinary people, particularly when it comes to economic matters, his life experience seems highly relevant. Because of the class into which he was born, Bush never found himself needing the kind of job 99 percent of Americans hold at some point, and the vast majority for most of their working lives. Bush was never at the mercy of a boss who could threaten his livelihood, never felt exploited and unappreciated at work, never suffered the petty humiliations so many Americans do at the hands of someone who happens to rank higher than them in their workplace's hierarchy, never went home with aching feet after a long day and no choice but to return the next.

Yet George W. Bush has succeeded quite spectacularly at convincing much of the public that he's just an ordinary Joe. The vulgar man who would exclaim "Feels good" upon starting a war is carefully hidden. The son of the elite, his life course determined by his family's wealth and connections, fades from view. And all that remains is the down-home Bush, the simple man with a good heart. No part of the Bush fraud should have been more difficult to pull off, yet none was accomplished so easily. It is not surprising that Bush would try to pass himself off as a homespun, plainspoken, regular guy. What is amazing is that he was able to make so many Americans -- not least the supposedly preternaturally skeptical press corps whose job it is to keep tabs on the truth -- buy it.

Shares