From the onset of the Cold War, the Republicans attempted to taint the Democrats as unpatriotic, in league with America's enemies without and within. With its end, one of the central organizing principles of the Republican political strategy dissolved. But in the aftermath of 9/11, George W. Bush and his political advisor Karl Rove reanimated the patriot game, and Democrats were conflated with terrorists and tyrants.

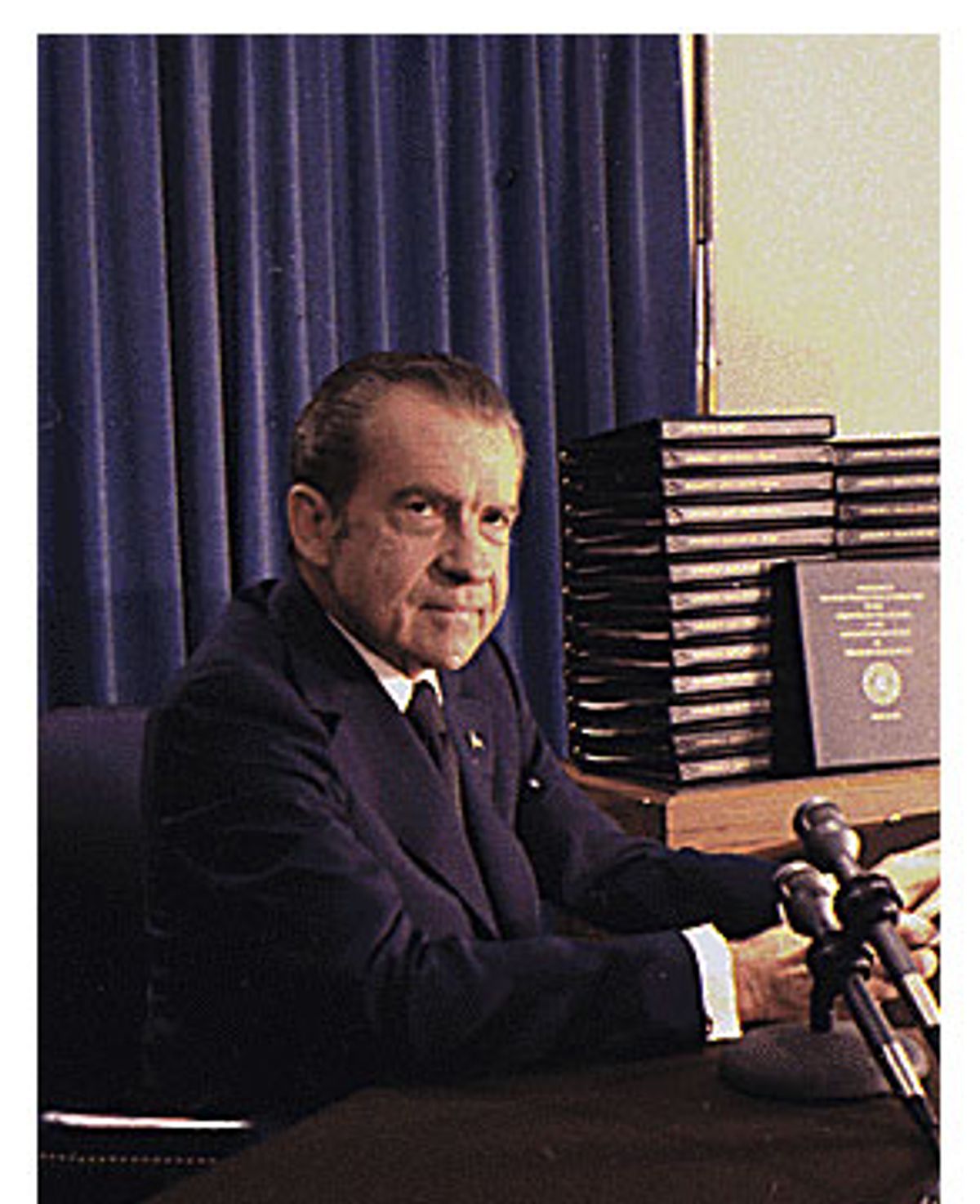

The founding father of the Republican patriot game was Richard Nixon, whose career was borne along by impugning the patriotism of Democratic opponents and uncovering subversives who he claimed represented the heart of the New Deal. His relentless ambition, however, was thwarted when he found himself confronted with a war hero, John F. Kennedy. In 1960, the game was over. But the Vietnam War gave Nixon the platform for his resurrection. Once he became president, the game of smearing the Democrats was reinvented as he set Vietnam veterans and hardhat blue-collar workers (veteran surrogates) against war protesters.

In the spring of 1971, a worrisome new political figure emerged to oppose his Vietnam policy. On April 22, John Kerry, wearing combat fatigues, his Silver Star, Bronze Star and three Purple Hearts, testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. "How do you ask a man to be the last man to die in Vietnam?" Kerry asked. "How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake? This administration has done us the ultimate dishonor. They have attempted to disown us and the sacrifices we made for this country."

According to Nixon's secret White House tapes, there were a number of fretful meetings held on how to discredit Kerry. Nixon, the ultimate opportunist, wanted to characterize Kerry as one, too. "Well, he is sort of a phony, isn't he?" Nixon says. "A racket, sure." "He came back a hawk and became a dove when he saw the political opportunities," Charles Colson, his hatchet man, says. Nixon sneers, "Well, anyway, keep the faith." Colson sends Nixon a memo: "Destroy the young demagogue..." The day after Kerry's testimony, Nixon held another meeting. Chief of staff H.R. Haldeman says, "He did a superb job on it at Foreign Relations Committee yesterday. A Kennedy-type guy, he looks like a Kennedy, and he, he talks exactly like a Kennedy." That sort of comparison could only incite Nixon's dread and envy. Nixon disbelieves that Kerry won medals for bravery. "Bob, the Navy didn't have any casualties in Vietnam except in the air," he insists. Three days later, Haldeman returns. "We've got some interesting dope on Kerry. Kerry, it turns out, some time ago decided he wanted to get into politics." In another meeting, Haldeman and John Ehrlichman suggest to Nixon that if Kerry led protesters who cut their hair and wore ties and allied with "the hardhats," they would win a majority to their side. "That's right," says Nixon. But, he adds, "They're against all that."

From the Republican side, Kerry's march toward the Democratic presidential nomination has appeared as another chance to refight the patriot game. But questions raised about the rationale for the Iraq War have brought to the surface the palimpsest of Vietnam. Bush, the heir of the Nixon party, facing a genuine war hero, critic of that war and this, finds himself scurrying to explain his apparent absence without leave from his National Guard service for an entire year during Vietnam. His White House is tossing scraps of records to the press that are only provoking additional questions about his prior false explanations. Democratic strategists are now planning to use the tape of Bush, wearing a flight suit on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln, declaring, "Mission accomplished," which Republicans were once aiming to use as the centerpiece of their campaign.

Kerry's appeal to veterans isn't simply because he's a veteran. For the Vietnam vets, he has come to stand for the male blue-collar worker of their generation, the ultimate swing voter. In the light of comparison, they are coming to see Bush as the privileged evader of service who now is standing with his wealthy friends against them. Kerry is the aristocrat as member of the band of brothers. Nixon's fear is being realized.

Marco Trbovich served in the Navy with Kerry, marched against the Vietnam War with him, worked in his campaigns, and is now the communications director of the United Steel Workers of America. "John's been in the foxhole," he told me. "He's endured, survived and never forgotten who these guys are. This is completely authentic. If you're a veteran of Vietnam you understand how unjustly the system can treat you. Now the economic system is treating them unjustly and Bush is responsible. John's credibility with working-class men who didn't get college educations is enormous. A guy who pretends and puts on a jumpsuit doesn't get it. "

Bush, in his interview this week on NBC's Meet the Press, styled himself as a "war president." But he finds himself in a quagmire of his own making and the patriot game has taken an unexpected turn.

Shares