Though I can see some of Baghdad’s American-occupied Green Zone from the roof of the house I live in — there, just across the river — the vastness of the enclosure, encased by imported barrier walls, means that to reach the public entrance I must drive a crazy labyrinthine loop through the city. With hundreds of thousands of other cars on the road, all forced to circumvent this American-made fortress, the trip can take 20 minutes to two hours, depending on the vagaries of traffic. At the public entry point, rows of concrete barriers and looping razor wire block the wide boulevard that turns off toward Saddam Hussein’s former palace complex. No cars can get into the Green Zone at the public entrance. When I go there, my driver, Thamer, parks his car in a parking lot right next to the barricades and I get out and proceed on foot, down a sidewalk flanked by walls of sandbags. A few yards along the sidewalk I get to the first of many checkpoints, where an Iraqi guard does a cursory bag search. Next, American soldiers with M-16s slung over their shoulders stand with Iraqi guards and inspect I.D.s. This is the only entry where Iraqis without special Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) badges can get into the Green Zone. Depending on the time of day, the line backs up along the sidewalk as Iraqis seeking jobs, or compensation for damaged property, or business contracts, or information about incarcerated relatives wait to pass through the security. Everyone at that point must show two forms of picture I.D. Since almost no Iraqis have passports, it can be a problem.

I get waved through using my passport and a press I.D. Next, the line enters an olive drab military tent, where it breaks in two — the right side for women and the left side for men. When my turn comes, I stand next to a table with my legs slightly apart and arms out to the side in a jumping-jack sort of pose. A young Iraqi woman (whose name I should probably know by now, considering she’s gone to second base with me on a number of occasions) pats and squeezes me from shoulder to toe. She asks me to turn on my camera and she pokes through the chaotic contents of my backpack. When she’s done, she always says, “Thank you.”

Having gone through the tent check, I am in the mini-America that is the Green Zone. To the left, up a driveway, and beyond a small grassy esplanade is the acre-size convention center that houses the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) office, the Iraqi Business Center, and the Iraqi Assistance Center, as well as a number of auditoriums used for press conferences and symposiums. Getting into the convention center requires another I.D. check, another pat-down. Polite soldiers who always seem to be hovering between a state of nervousness and boredom patrol the massive three-story atrium just inside the doors. This area is so cavernous that it feels perpetually empty, like an airport at 4 in the morning. Saddam’s parliament formerly met in this building, and the whole place was kept pristine in anticipation of Saddam’s occasional visits. Now, random computer printout signs point the way to several different offices (though not the ones people tend to be looking for). On some walls and pillars, posters for events that happened last week, last month, and last year are stuck at sloppy angles, waiting for the dried-out adhesive tape to give way completely. Tiled pictorials the size of boxcars ring the atrium’s second level. One depicts Iraqis surrounded by doves of peace. Another shows Iraqi soldiers decapitating dog-headed snakes and proclaims, “The martyrs are better than all of us.” They demonstrate the typically schizophrenic messages of Saddam’s time: Iraqis are lovers of peace, Iraqis are fierce fighters. Over another hangs a banner sent to the troops just after the war, proclaiming “Mooreland Elementary School, U.S.A.” in large red and blue bubble letters.

The convention center acts as the nexus for the Iraqi public and the CPA. It’s the only part of the Green Zone most visitors get to see. But it’s definitely not where the action is. The main hub for CPA activity, its inner sanctum, is the Republican Palace. (Immediately after the war, the Americans renamed it the Freedom Palace, but that moniker just didn’t take.) The palace lies a couple of miles from the main Green Zone entrance. Shuttle buses operated by Kellogg, Brown and Root (the Halliburton subcontractor that handles much of the military’s support structure here in Iraq and on bases around the globe) loop through the Green Zone, ferrying people to the Republican Palace, the hospital, the PX, and various military and contractor camps. The buses are driven by older American men who get paid very well for coming to Baghdad. And there’s another perk: If they stay for a set amount of time (a little under a year, one of the drivers told me), they don’t have to pay any taxes.

As you go from the convention center to the palace, you pass the Governing Council building, a boxy sand-colored tower with abstract metal figures making a failed effort to be a sculpture out front. Then there’s an empty stretch of road where a lone armored personnel carrier is always parked up on the curb. Once while driving past, I watched a soldier meticulously sweeping a small plot of sidewalk in front of the APC while another soldier sat up top, alternately sighting down his gun and waving a pink fly swatter. Further along the road come the crazy Saddam-built marble monsters where he, his family, and his inner circle lived and plotted (when not living and plotting in the scores of other palaces he owned around the country). I remember watching CNN during the war and seeing some of those very buildings get bombed, especially a modern ziggurat that spent one TV night haloed in flames. Now they’re half collapsed, mostly empty, and covered in dust. Some could almost pass as remnants of a war fought long, long ago.

I went to the Republican Palace recently to have lunch with Karen Walsh, a USAID program officer and CPA liaison. Karen works in the palace and lives in a prefab trailer right out back. I got a ride to the palace with one of her co-workers from the main USAID office at the convention center. Like most contractors in the Green Zone, USAID has its own fleet of SUVs and employs Iraqi drivers to zip them around without having to wait for the shuttle buses. As the nerve center of the entire American occupation, the Republican Palace requires a whole separate level of security. Anyone without a proper badge must swap out an I.D. for a visitor’s badge, get the familiar pat-down and bag search, and be accompanied at all times by someone with correct authorization.

Inside the palace most rooms have been converted into warrens of offices, often complete with recently imported (and decidedly un-Iraqi) fabric-coated cubicle separators. CPA employees hustle up and down the high-ceilinged halls, stopping one another to confirm meetings and discuss e-mail memos. I walked with Karen, who is in her 30s with long blond hair, bright blue eyes and a determinedly fast stride, to the mess-hall area in the center of the palace. It’s a little weird to use the term “mess hall” when referring to what is really a grandiose ballroom with marble floors and crystal chandeliers. This was Saddam’s presidential palace, his showplace for greeting visiting dignitaries. Now it’s a cross between an army barracks, a start-up company office, and a model U.N. convention.

At one end of this faux-Versailles room, Pakistani workers in white uniforms preside over steam tables that serve up traditional American cafeteria food: sloppy joes, boiled hot dogs, canned peas and carrots. A cloth-covered banquet table bisects the center of the room, offering up plastic bowls with pieces of layer cake and syrupy pie. Over a hundred tables fill the rest of the room and even extend into adjoining hallways.

When Karen and I arrived, most of the tables were packed by the lunchtime crowd: American civilians dressed in the Friday work-casual outfits favored by CPA employees, soldiers in fatigues with their rifles carefully placed beneath their chairs, and private Force Protection Service guards wearing jeans and T-shirts and wielding soldier-size guns. (Force Protection Service, or FPS, is a catchall phrase for private companies hired by the CPA and contractors to supplement the military security. FPS men tend to be former special operations soldiers from the United States, Britain, Australia and South Africa. As the military continues to phase out of front-line duties in Iraq, the private security companies will be increasingly responsible for safeguarding the American presence here — an important fact that has received little publicity.) While in the palace, I saw just a handful of Iraqis. Half of them were cleaning staff.

I sat with Karen at a table in one of the hallways and we talked amid the typical cafeteria din of scraping chairs and conversational white noise. She’s been in Baghdad almost nonstop since about the time of the official end of the conflict, when Bush declared on May 1 that “major hostilities” had ended. “I’m an original ORHAian,” she said. (“ORHA” stands for Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance, the previous incarnation of CPA.) When she arrived, the whole ORHA staff under the direction of Jay Garner consisted of 250 people. They thought it would be enough. Now she estimates the CPA staff at around 1,500.

Staff turnover within the CPA is ongoing and enormous, a virtual tsunami of outgoing and incoming personnel. Most CPA employees sign up for the minimum three-month stint and don’t renew their contract. Some don’t even make it that long. I heard about a guy who flew to Baghdad, worked for one day at the palace, and then high-tailed it home on the next plane. Since Karen’s arrival, there’s been a full turnover of all senior advisors. People leave due to safety concerns, bureaucratic frustrations, and untenable living conditions. “Everyone comes with good intentions,” Karen told me, “but the weight of this place can really get to them.” Another CPA employee I spoke to (on the condition of anonymity) was a little less generous. In his view, a lot of Washingtonians come to Baghdad to pump up their résumés and then get the hell out.

Whatever the reason, that constant brain drain means that, at any given moment, a large percentage of the CPA staff is struggling to figure out what it took their predecessors three months to learn. The task is enormous. Basically, they’re trying to turn Iraq into a functioning state. That means fixing all the ministry-controlled infrastructure problems (power, water, sewage, phones, education, hospitals) while simultaneously trying to funnel decades of corrupt socialism into a free-market economy (with a new constitution and open elections thrown in, too). And just as people who show up to work here get a handle on the situation, it’s time for their goodbye party.

Some of the CPA honchos here may just be putting in time as a career move, but Karen definitely isn’t. She didn’t strike me as all that happy, but she certainly seemed dedicated. “People who survive understand that the goal is greater than personal satisfaction or glory,” she said. “The mission is greater than you.”

But the clock is ticking for this mission. American proconsul Paul Bremer has declared that, come hell or high water, the transfer of power will take place on July 1. There’s a sense of both resignation and a mad scramble at the CPA. There’s no way that everything can get done on time, but Bush is up for reelection four months after that, and they have to get it done. One CPA staffer told me that Bremer had sent around a memo saying something along the lines of, “I know I told you that the sprint would eventually become a marathon. But we’re back to sprinting again.” A different anonymous staffer told me, “It’s like a ticking bomb. If the ministries don’t get their shit together, things could go really bad.”

As we sat eating sandwiches off plastic plates and drinking coffee from Styrofoam cups (unsettling, considering the number of Kellogg, Brown and Root meals served every day in this recycle-free country) a co-worker of Karen’s stopped by and asked to join us. Karen said we were doing an interview. The woman laughed a little nervously and said something about how much she hated finding people to sit with. She had to be sure to walk with a purpose and avoid making eye contact with boring people, lest they wave her over. “It’s just like a high school cafeteria,” she said.

I asked Karen about the social environment of the Green Zone. As someone who works from 7:30 a.m. to midnight every day, she doesn’t have much of a social life. She spends most of her time in meetings that coordinate USAID programs with the CPA administration. When she does have free time, she goes to the newly constructed gym. Tuesday nights there’s karaoke in the palace. Once in a while Karen will go to the sports bar in the basement of the Al-Rasheed hotel: alcohol and the movies shown in the palace are sometimes the only escape. The Al-Rasheed sits opposite the convention center and used to house CPA employees, but since a mortar attack last October that nearly killed visiting Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, the rooms have remained largely empty. There are a few shops on the first floor and a mess hall. And there are rumors that some military personnel have taken up residence on the lower floors. But, for reasons no one really seems to know, the Al-Rasheed is now off limits to the press. (My personal theory is that the CPA powers that be would rather not have reporters in the one public place in the Green Zone where people are getting truly trashed and talking about how fucked up everything is.)

Karen said that one of the hardest things to deal with is the lack of privacy. She lives in a room that takes up half a trailer — and she has a roommate. On the other hand, she admitted, it could be a lot worse. About 10 feet from where we were having lunch I could see a phalanx of large wooden doors. Behind those doors lies another huge ballroom (complete with a mural of Scud missiles soaring over a deep blue sky) in which 350 CPA-ers — privates and officers; senior-level civilians and low-level flunkies; men and women — sleep in tightly packed-together bunk beds. As we finished our lunch, I watched a disheveled older man wearing a jacket and tie and clutching a pillow to his chest resignedly open one of the doors. I could swear he looked as though he was about to cry.

In the early days of the Green Zone, before suicide bombers and roadside explosives became the daily diet of risk in Baghdad, Karen used to leave the Zone and get out on the streets of the city. But for a long time now, soldiers, Coalition Provisional Authority employees and contractors have had to adhere to strict orders with regard to their movements. Soldiers leave on planned, heavily armed patrols. CPA employees and contractors occasionally make daylight visits to ministries or power plants. When they go, they travel in small convoys of humvees and military escorts. They are forbidden to go shopping on the streets of Baghdad or eat in a restaurant or visit the homes of their Iraqi co-workers. Some occasionally break the rules and sneak out. My roommates and I have occasionally sent cars to pick up furtive Green Zone escapees and bring them to our house for dinner. I’m sure others find ways to get out as well. But most don’t risk it for fear of getting hijacked or bombed or just getting caught. Recently, a contractor I met who lives and works in the Green Zone described standing on the inside of that last line of razor wire and looking out at the city beyond. It was an incredibly sad feeling, he told me. Here he was living in the middle of a city that may as well have been on the other side of the world.

The isolated nature of the U.S. occupation has always been an issue. Back in May I met a man working at what was then ORHA. He raved about the stupidity of holing up in the palaces, of not being out on the streets, available to the Iraqi people. Now, with the increasing attacks, it’s too late to do anything about it. The Iraqi hearts and minds that the Bush administration talked about winning are focused resolutely on American decampment. Despite the well-intentioned work being done behind closed doors, Americans are, first and foremost, inaccessible occupiers.

On a recent sunny day, I walked around the American section of the Green Zone. Tanks and jeeps lined the wide boulevards, men and women jogged past me in shorts and T-shirts.

The Green Zone Restaurant occupies a corner of an otherwise barren intersection about a half mile from the army hospital. Though it started last summer as a handful of open-air tables and small-kitchen shack, it’s since been enclosed in a sort of windowed tent. For a long time, it was the only private restaurant in the Green Zone owned and run by Iraqis, though I’ve heard that, recently, a Chinese restaurant opened somewhere. The Green Zone Restaurant serves a small selection of pizzas, burgers and Iraqi kebab. You can also order a “nargeelah” — a floor-standing glass water pipe used for smoking mellow fruit-flavored tobacco. I stopped there one afternoon to get a soda and sit down for a bit. Soldiers sat in clumps around the tables, joshing and sharing nargeelahs. By the back, one very young soldier sat hunched over a burger, eating as though he hadn’t seen food in days.

When I went to pay for my soda, I realized I only had Iraqi dinars and not dollars. Sometimes that’s a problem in the Green Zone, where the dollar is king. In fact, some entrepreneurial young Iraqis sell dinars as souvenirs to Americans in the zone. The Iraqi guy behind the counter laughed when I paid with dinars but kindly accepted them as viable currency.

I sat with three soldiers who were noodling with a recently purchased chessboard. All three — two men and a woman — worked in the hospital and, after a year, were preparing to ship out in the morning. The entire hospital staff was going to turn over — another brain drain. The soldiers told me they felt nervous about handing over the hospital to a fresh-from-the-U.S. staff, but they were definitely ready to go home. One guy said, “A year away and you miss everything. Every birthday, every holiday. It’s a year you’ll never get back.” His friend said, “Aw, shut up and play chess.” They played and talked and offered me a hit from their nargeelah. “Candy-flavored smoke,” one of them called it. They told me how they hated to go home without having seen any of Iraq. Forget about leaving the Green Zone — they could barely leave the hospital. I asked if they spent much time with the civilians in the Green Zone. I had heard, for instance, that the Bechtel people had a barbecue on Thursday nights. They had vaguely heard of Bechtel, but they had no idea where those people lived.

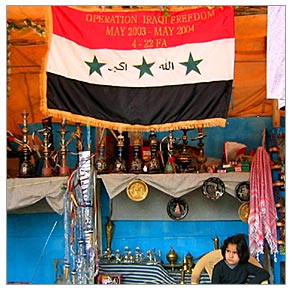

The Green Zone has a PX where you can buy American brands of soda and candy and electronics and cold medicine and greeting cards and backpacks labeled “AWOL.” For a long time, the whole PX was housed in a skinny trailer, but they’ve recently expanded into a bunker-type building. It’s the only place I know of in Iraq that has the technology to take credit cards. For 15 bucks each at the PX, you can buy DVDs to watch on your computer. But not many people buy their DVDs from the PX. Nearby, down a dirt street, Iraqi vendors sell hundreds of bootleg DVDs for about a quarter of the PX price. This street has been turned into a spare marketplace. Kiosks selling the DVDs, souvenir flags, leather sidearm holders, crystal geegaws , rugs, nargeelahs, Saddam watches, cigarettes and (of course) dinars stretch for about a block before petering out into the dust. The kiosks are owned and run by Iraqis who live in the Green Zone. It’s a chance for them to make some money off their uninvited neighbors.

I wandered up and down the marketplace, looking at the stuff. Americans both in and out of uniform wandered around too. There was something truly unnatural about the scene. It felt like a dirtier version of a Disney “Iraqi marketplace,” complete with real Iraqis. It brought home the reality of the Green Zone: Within its concrete barriers, Iraqis are the interlopers.

The July 1 transfer of sovereignty will change that. But it’s not going to be easy. No one really knows at this point how it will even work. If the United States leaves outright, the subsequent struggles for power could lead to civil war. If the United States stays in an overbearing regent sort of role, it’s bound to perpetuate the violence against those seen as U.S. collaborators. These days, Iraqis seem to feel that the American presence is responsible for pretty much all the ills of the country: the violence, lack of power, lack of jobs. With the U.S. election approaching, the Bush administration has a strong impetus to stick to the deadline and just get away from this debacle.

As I was leaving the marketplace, an Iraqi man held a book up to a browsing soldier. “This is dictionary,” the Iraqi man said. The soldier wagged his head back and forth. “No, no, no,” he said. “I don’t want to ever speak the language.”