There have been faint rumblings over the past few months that with "The Passion of the Christ," Mel Gibson may have changed the face of cinema forever. I think he has: He's made the first true Jesusploitation flick, a picture that, despite its self-righteous air of grave religiosity, is barely spiritual at all. Instead, it's the most macho movie about Jesus ever made, one that catalogs his physical suffering in a businesslike visual database of flayed flesh and spurting blood. If we turn away from "The Passion of the Christ" -- in other words, if we fail to give in to Gibson's bullying tactics, which are more like a peculiar form of martial arts than a style of filmmaking -- we will have failed the spiritual test. The way Gibson has spoken of "The Passion of the Christ," in his TV interview with Diane Sawyer and elsewhere, liking or disliking the movie isn't a question of taste: It's a matter of character. If we flinch from the sight of nails tearing through flesh or the sound of human bones cracking, we're automatically denigrating the magnitude of Jesus' sacrifice. "Are you man enough to take it?" is Gibson's relentless unspoken demand, and the answer had better be yes.

Gibson has worked hard to make us all believe that "The Passion of the Christ" is more than a movie. Yet he's used some of the oldest techniques in the moviemaking textbook -- some of which, I believe, predate the Old Testament -- to put together what is essentially a very dour, pedestrian picture. When Judas leans in for his kiss of betrayal, the camera kicks into slow-motion; as an audience, we're supposed to respond with the universal brain-wave pattern that spells out, "Say it ain't so!"

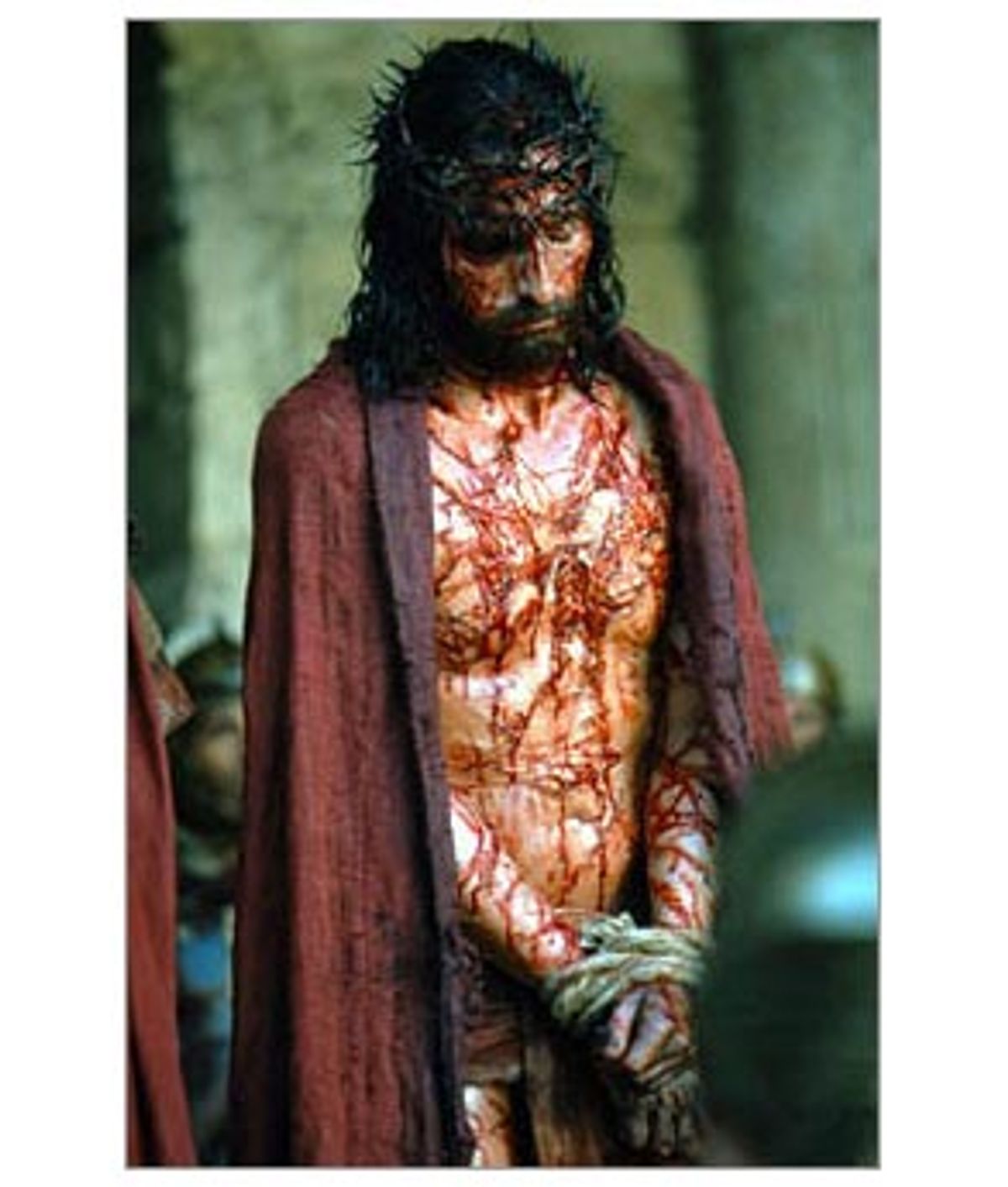

But alas, it is so: Jesus (played with grim, beleaguered resignation by Jim Caviezel) has been praying in the Garden of Gethsemane, where a hissing, effeminate Satan, pinched and cloaked and looking like a refugee from a Pilobolus-knockoff troupe, has tried unsuccessfully to tempt him over to the dark side. Jesus resists Satan, only to be arrested by a bunch of Roman-soldier thugs. Later, in a mercilessly protracted sequence, they'll literally tear the flesh on his back with canes and a cat-o-nine-tails whose tentacles are fitted with hooks and shards of broken glass. Their faces gleam with the sadistic glee usually reserved for movie Nazis; with their bald heads and rotten teeth, they're a kind of skinhead shorthand for "evil."

Gibson sure loves his shorthand, such that he leaves large essential chunks of his story either wholly ignored or slickly glossed over. You had better know your Jesus 101 before you set foot in the theater, or you're likely to be mystified as to what made the guy so great in the first place -- or, more essentially, why he was so cruelly persecuted. We see the Pharisees (it's not hard to notice that all of them have conveniently Semitic hooked or bulbous noses straight out of central casting) agitating for Jesus' blood, and most of the crowd (in the parlance, they're called "rabble," the better to underscore their boorishness and separateness from the true Jesus lovers) seem to agree with them.

But why? The best we can figure is that Jesus is a rebel who, with his message of love and brotherhood (useless business, that), has somehow disrupted the natural order of things. (You'd think he was half of a gay couple trying to get married or something.) A few people, such as the dewy Mary Magdelene (Monica Belluci) and, of course, Jesus' own mother (Maia Morgenstern), gaze at him adoringly, and with great apprehension over what they fear will happen to him next. (The women have very little to do in this picture other than to show anxiety and tearful empathy and to mop things up with little cloths, suggesting that as far as women's roles are concerned, Catholicism hasn't changed a whole lot in 2000 years.)

With a few notable exceptions, Jesus doesn't have many friends to help him in the clinch. He has been betrayed by some of the people he trusted most, and, for believers and nonbelievers alike, I think that's an essential part of the story: His sense of isolation, and his brief moments of despair, make him distinctly human. But Gibson is much less interested in helping us understand Jesus' human frailty -- the very thing that's supposed to give his sacrifice so much resonance -- as he is in rubbing our noses in the horror of his mistreatment. Gibson's cinematographer here is the extraordinarily gifted Caleb Deschanel, who gives the movie's early scenes a spooky, misty, ominous look: His craggy, moonlit landscapes, combined with the strangeness of the language (the movie is in Latin and Aramaic, with English subtitles), add up to a mysterious kind of poetry that, for the movie's first 10 minutes at least, suggest that the picture might have some element of the mystical, at least a glimpse of the spiritual underpinnings that Catholicism relies on.

But Gibson is so fixated on Jesus' suffering that spirituality is only a footnote. The strange thing about "The Passion of the Christ" is that Gibson doesn't seem particularly interested in proselytizing: His movie is clearly made for the people who already "get" Jesus -- by itself, it's not likely to win Christianity any converts. Part of the problem is that we have very little sense of Jesus as anything other than a victim. We see him in a few fleeting flashbacks: Caviezel is very cannily cast, because when his Jesus isn't suffering, he's spiritually and sexually magnetic. In a very brief scene, we hear him telling his followers to love their enemies -- What good is it to love only those who love you back? he asks -- and his words seem so sensible and grounded that, Jew or Gentile, believer or non-, you might find yourself leaning forward to listen.

But Gibson cuts away from the scene with a "That's enough of that" efficiency, back to more scenes of Jesus being beaten, bloodied and humiliated. For Gibson, religious belief is clearly some kind of endurance test. That may be inherent in Catholicism itself: I remember, when I was a young and rather devout Catholic child, asking my mother why Protestant churches had crosses but no bloody Jesus figures hanging from them. She explained that Catholic iconography was different from that of other Christians, which suggested to me (and probably to her, a Catholic convert who knew how the other half prayed) that garden-variety Christians were all well and good, but we Catholics really knew the score: To be a Catholic, you had to be able to take the heat -- to accept the nature of Jesus' sacrifice in all its bloody glory. You couldn't go to Mass, or get to the end of your rosary, without having to reckon with the blood he shed.

Gibson, in a stroke of what can only be called marketing genius, has shown his movie to members of select religious groups over the past few months, and he's made much of the fact that it has found favor not only with Catholics but with Christians of many stripes, particularly conservative ones. It obviously hits some angle of Jesus' story that they feel needs to be stressed. But I think that, strangely, Gibson's fixation on Jesus' suffering actually diminishes it in some ways. I say that because, in Catholic school in the 1960s, the suffering of Jesus was treated as a type of pain almost beyond our comprehension: Picture the worst kind of physical suffering imaginable and multiply it by 10 -- that's how bad it was.

Gibson has chosen to go for realism here -- realism defined, that is, from what we can glean from the Gospels, which is relatively very little, but never mind that. By spelling out every detail of Jesus' suffering (and including plenty of go-for-broke camera shots, like one of a nail poking through the back of the cross, dripping glossy blood), Gibson has turned that suffering into a kind of cinematic laundry list. The images are so relentless they become numbing; paradoxically, as the details pile up, they become more of an abstraction than concrete proof of anything. We're reminded that human bodies -- even the body of Jesus, whom the Catholics believe to be both God and man -- can handle only a finite amount of abuse before they simply give out. We're left with a fairly clinical understanding of the pain Jesus endured, but there's no spiritual glow to the mystery of his sacrifice; if it's there, it's caked in so much dried blood that we have no sense of it.

And none of this, of course, answers the question that's on everyone's lips: Is "The Passion of the Christ" anti-Semitic? If you can look beyond the Pharisee baddies, I think the answer is that Gibson is too zealous in his own beliefs to allow much space for anyone else's. It's a "My faith's bigger than yours" approach -- as if he believes that by being the loudest man in the room, he'll somehow make himself the only one.

That is, of course, his right. If you're a believer in the one true faith, any work of art (or, more accurately in this case, propaganda) you put out there is going to have a slant as pronounced as a lightning bolt. Even so, flipping back through some of the images that Gibson so brashly put on the screen, and reminding myself how many times I wanted to look away, I can't help wondering: In the same position, what would Jesus do? And if he flinched, would he be any less of a man?

Shares