Like a ghost, he moves among rooms of an empty house where he lives and doesn't live anymore.

"You do so much work around the house, you become part of it," the man says softly.

Sturdy house, the man says. Built in 1950. All oak joists, plaster walls. Insulated.

Outside, the gray sky grows dark. A fall wind carries the first breath of winter.

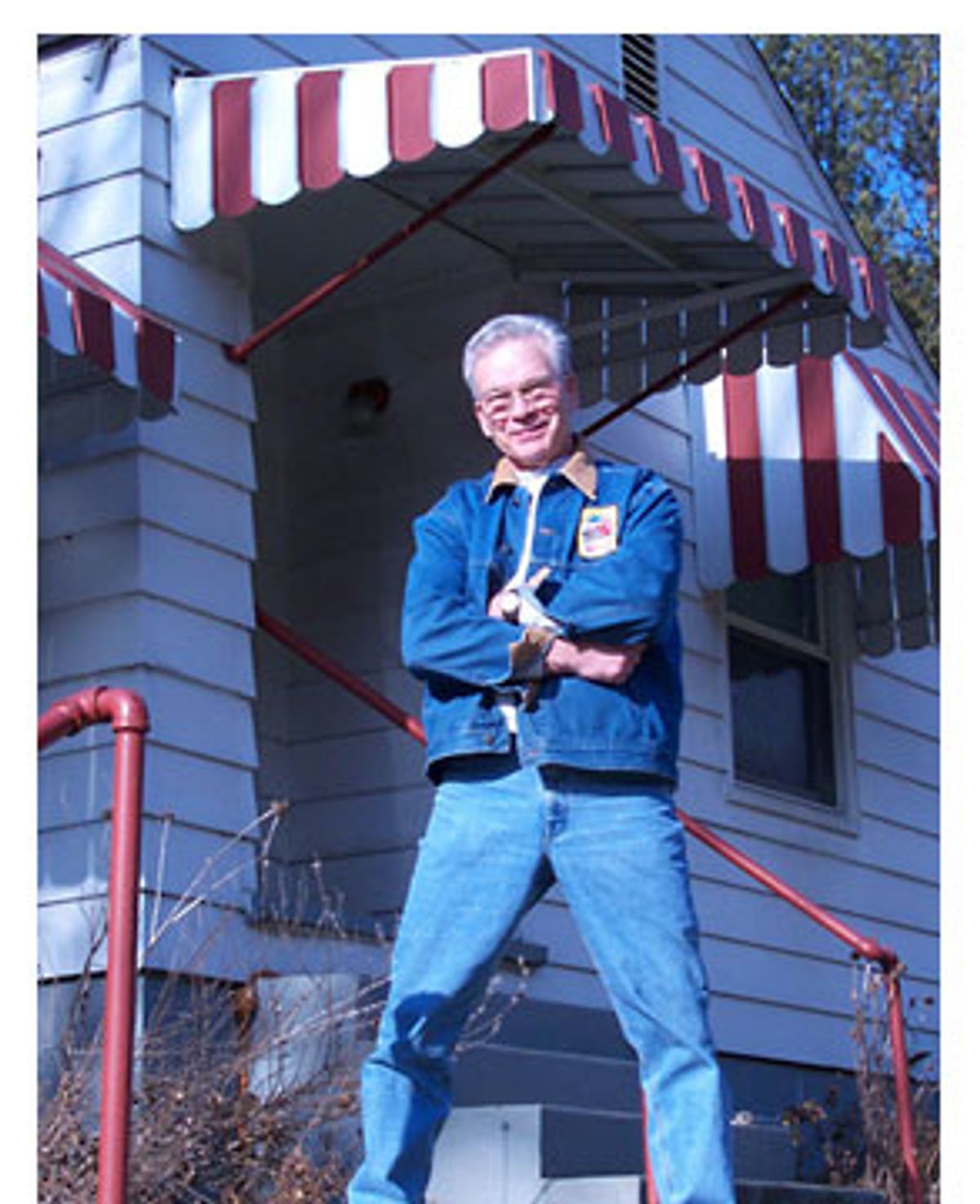

They've given him until the end of the month to be out. Instead, Ed Burnette, a compact man who wears aviator-style glasses with thick lenses, says he'll turn over the key next week.

Rising demand for electricity is bringing boom times to coal country Pennsylvania, the nation's fourth-largest coal producer. But with prosperity, the boom is creating havoc for some people who make their homes in rural Greene County.

Burnette, 71, says he and his wife, Kay, 61, are among at least a dozen families here who have been forced to move in recent years because of mining damage.

They are all victims of improving technology. High-efficiency deep mining equipment removes nearly every last clump of coal from seams far below their homes, causing the ground above to fall almost as fast as the mineral is removed. Houses twist, windows crack, ceramic tile crumbles like crackers.

And there's nothing that people like the Burnettes can do about it.

The problem began generations ago. Companies bought up coal rights all around Greene County. That allowed one person to own what's underground and another person to own the surface of the same piece of land.

For years, dual ownership of mineral and surface property rights wasn't a worry. Then the owner of the coal decided to claim what belonged to him.

State law requires companies to restore water and fix structural problems caused by deep mining, but it hasn't always worked the way it was presumably intended. Prodded by a federal mandate that found numerous deficiencies in state law, Pennsylvania is coming up with new protections for homeowners from mining damage. For many homeowners in Greene County, the new safeguards are coming a little late; they won't be available for at least another year.

In the meantime, settling damage claims with coal companies can be a high-wire act.

"Let's face it," says Thomas Hoffman, spokesman for Pittsburgh-based Consol Energy, which mines coal in Greene County. "There are a lot of people living in rural areas who would want to sell their place."

"What we do is balance our rights against the understandable concerns of homeowners."

But critics say the law gives mining companies the upper hand in dealing with residents while the environment is being spoiled.

"Greene County is ruined," says Dick Patterson, 67, a beef farmer who lost his wells, and has lain awake nights listening to the rafters of his house groan and split after his farm near Waynesburg was deep-mined three years ago. "The water will not come back."

Deep mining often disturbs rock formations that pool and filter drinking water, says Wyona Coleman of the Pennsylvania chapter of the Sierra Club. "The mining industry claims the water will return," says Coleman, who chairs the chapter's mining committee, "but we haven't seen it."

Burnette brought his wife to this one-story frame house in 1984. They fell in love with the aluminum awnings and fire-engine red shutters. Paid cash.

Burnette had just retired after working 30 years at a General Motors stamping plant. There's just the two of them now. They planned to finish out their days in the village of Spraggs, about an hour's drive southwest of Pittsburgh.

The Burnettes' retirement plans soon collided with advances in mining. A highly efficient form of coal recovery, called longwall mining, was introduced in Pennsylvania in the late 1960s.

Since then, giant augurs, conveyors, and related equipment have improved dramatically as coal production from longwalling climbed to 75 percent of all underground mining in the state.

In Greene County, where Spraggs is located, some 30 million tons of coal are mined each year, according to chief county assessor John Frazier. That's 830 loaded rail cars leaving every day of the year.

Most coal is burned to make electricity. And the Burnettes' home is part of the price paid to make PlayStations glow and heat George Foreman grills all across America.

Bargain prices are spurring demand. Delivered coal costs less than table salt at the supermarket. Coal is also cheaper than other fuels. To produce the same amount of heat, coal costs one-third as much as oil, and one-seventh the price of natural gas, according to George Ellis, president of the Pennsylvania Coal Association, a Harrisburg, Pa.-based trade group. There is enough coal in Greene County to keep existing mines open for another 30 to 50 years, he says.

But subsidence damage isn't figured into the cost of coal.

Take Leigh Shields' roadside nursery and 19th century log cabin, a quarter mile up the road from the Burnettes.

The ground sank more than four feet in 2002 after giant augurs chewed through a coal seam hundreds of feet below his land. A 75-foot-tall white pine tree in his yard snapped and toppled. Roberts Run, a stream across the road that Shields says once supported foot-long bass, stopped flowing.

"There's only one remedy for this: You have to ban longwalling," says Shields, who is 53 years old. "Develop something that doesn't destroy the whole earth."

That's not likely to happen any time soon.

Pennsylvania easily leads the nation in coal removed by longwalling, says Carol Raulston, spokeswoman for the National Mining Association, a Washington-based trade group. The value of that coal is conservatively estimated at $1.5 billion annually. Longwalled coal also provides jobs for 7,500 Pennsylvanians.

"It's an American nightmare," says Shields' sister, Diane Brendel, 57, a retired grade-school teacher whose nearby home is braced by stacked timbers after it twisted and cracked from mining in 2000. "It has taken away my faith in the law."

Burnette is pointing again. See the gaping crack in the foundation? He probes the void with his hand, as though somehow disbelieving. Over here is where black water surged down the cellar wall the day the septic tank busted.

Here's where a trench was hammered into the floor and filled with stone to contain groundwater that suddenly spurted from the wall. That new pump over there: It goes on every three minutes, he says.

This is the house where, two years earlier, an official from Consol put his arm around Burnette's shoulders, friend-like. "Mr. Burnette," the official said, "you're protected by the law."

"Yeah, I know," Burnette answered, pointing to a shotgun. "It protects me from killing you."

Burnette isn't naming names though.

That was April 2001, when the mining began under Burnette's house. After that, it was like his home belonged to someone else.

As problems arose -- doors that wouldn't open, burst pipes -- a stream of workers came through to try to right things. Meanwhile, Burnette's negotiations with the coal company dragged on two years.

"Well, I think I'll get an attorney," Burnette said when talks faltered.

"Go ahead," he remembers the company man saying. "We have 500 of them."

In the end, people might say the Burnettes made out all right.

Consol met its legal obligation to supply water and gas to the Burnettes, and the company paid to fix their home. And when repairs were not enough, Consol bought them out at what the couple says was a fair price.

A settlement has been more elusive for other families in the valley, including Diane Brendel and husband Roy. Their dispute with Consol is in federal court.

"I don't want to trade my mansion for a double-wide," says Roy Brendel, 59, who took early retirement as a guidance counselor, and whose damages include a concrete swimming pool that split and emptied overnight. "I want my life back."

Meanwhile, back in the Burnette house: Now feel the twisted cellar steps under your feet, Burnette says. There, see the crumbling plaster in the kitchen?

Here is where a contractor hired by Consol studied a wide, jagged opening above a kitchen doorway. "Just a little cosmetic surgery," the contractor announced.

Burnette says his wife turned away, silent.

Maybe the guy was kidding, says Burnette, his face smooth as oiled leather. But some things you shouldn't kid about.

Burnette thinks of nearly freezing to death on the Korean battlefield in the early 1950s as a Marine. The experience hardened him, he says. But it didn't prepare him for the last few years.

"I could see my enemy then," he says, his voice soft. "And I had a weapon to fight with. But here, I have no weapon."

He can't see the mine that ruined his well and wrecked his house. What's more, the company followed the letter of the law in extracting the coal -- their coal, coal that in recent years became highly profitable to extract.

"You work all your life, making a nice place to live," Burnette says, barely a whisper. He doesn't finish.

Still, Burnette says the damage to his house is no worse than others in the valley. Truly, he's a grateful man.

Consol offered to pay the Burnettes $130,000 for their house and land. They accepted. "I thank the Lord for that," he says.

Next week the Burnettes will move about an hour away to a new modular home across the state line in West Virginia. The house is just four miles from where Ed Burnette was born, and a cemetery where much of the Burnette family is buried. He says he likes the idea of living close by.

Anyway, Burnette says, "There's no community here anymore. No one wants to move here."

What's more, there will be plenty of places to hike near the new house, which Ed Burnette likes to do more than anything.

"Checking on the woods," he calls it. He hunts, too. Out in the woods he says he can see how longwall mining is reshaping the landscape, far beyond his house. "I seen hills pull apart," he says. "Every stream is dried up. There's no water anywhere."

But hiking in West Virginia won't be like hiking and hunting the hollows around Spraggs with friends, he says, some of whom go back 42 years. Hunting with friends, he'd sometimes play "dog," and roust deer from hiding places for the others.

The guys would joke and give him gummy bears. He chuckles about this, but his laugh is without mirth.

Burnette tugs the door to his house shut behind him, not bothering with the lock. The wind is picking up. The weather is turning colder.

Burnette gets into his Subaru, starts it, and eases the car onto winding Route 218, gently accelerating past barren cornfields.

Oh, it'll drive you crazy if you let it, Ed Burnette says. He doesn't look back, not even in the rearview mirror.

Shares