After my parents got divorced, every time my dad would come to the house he'd comment on how bad the yard looked. "Those bushes are pretty overgrown, huh?" he'd say, smugly, or, "Doesn't anyone mow the grass around here?" At the time, his comments depressed me, as if our scrappy lawn somehow signaled that our family was falling apart. Now I recognize that he was comforted by the fact that our lives didn't continue smoothly without him, that his absence was felt.

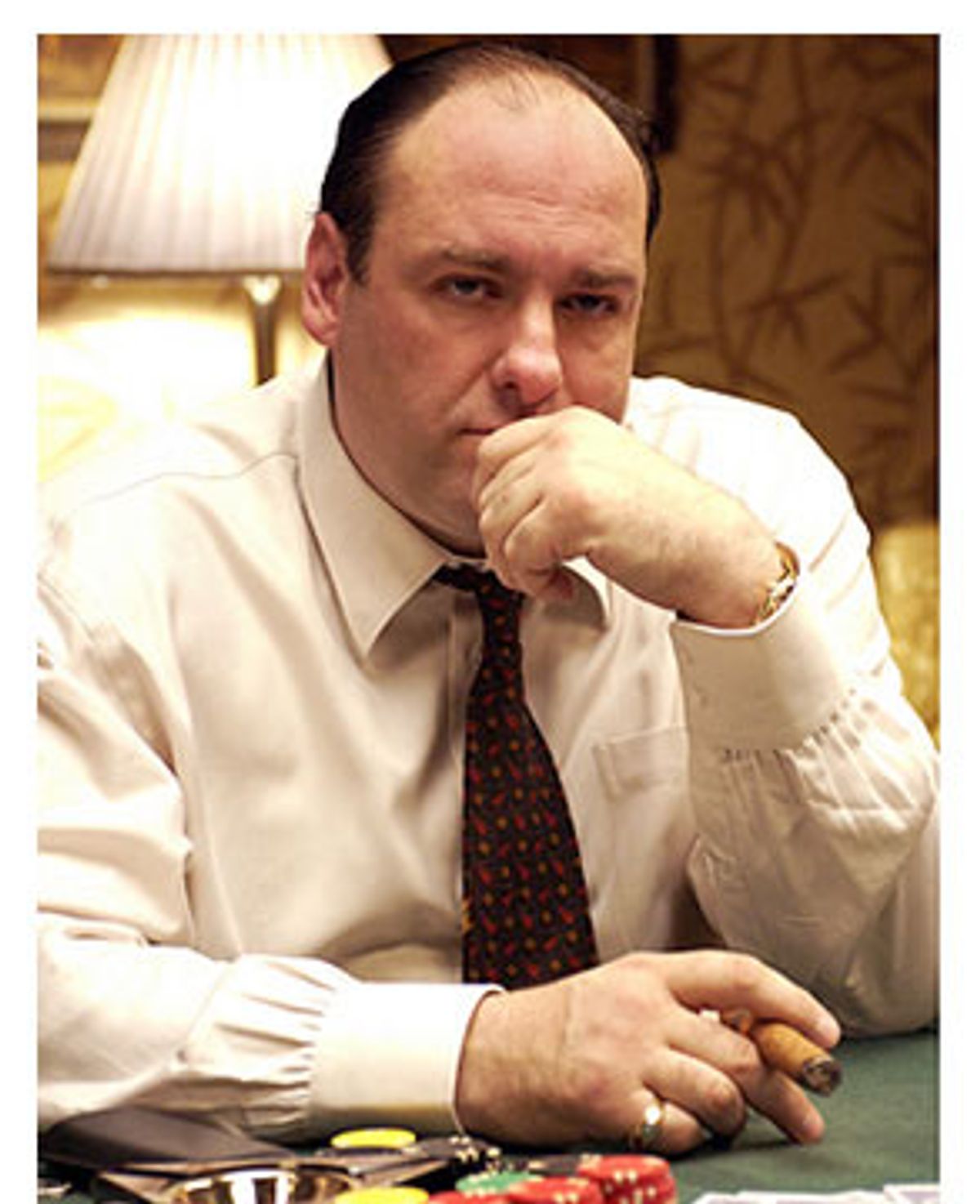

This season finds Tony Soprano lurking around his old house like a ghost, looking for signs that his family needs him. (Spoiler alert! This article discusses the first four episodes of this season of "The Sopranos." If you don't want to know bits of the plot from these episodes, you should stop reading.) Even when he can't manage a conversation with his wife and kids, Tony (James Gandolfini) seems to take solace in his role as the family's provider and protector. When Tony discovers that A.J. (Robert Iler) and Carmela (Edie Falco) have had a run-in with a black bear in the backyard, he asks Carmela, "Why didn't you call me when this first happened?" He gives her extra money and insists that she and A.J. stay in a hotel until it's safe again, but Carmela refuses. So, he absurdly sends some flunkies over to sit in the backyard with a rifle, just in case the bear returns.

Since the first season of "The Sopranos," Tony has embodied the contradictions of the male psyche, the Catch-22 of wanting to be in charge and in control, but also desiring genuine love from those around him. In the process, as the lead character in surely the most influential television drama of the last 10 years, he's become an American archetype: the traditional man unsure of his place in a changing world, the alpha male struggling to gain respect from those who resent him for his domineering ways. But this season many of the characters find themselves in similar binds, looking for someone or something to turn to, but coming up short and reverting to their same old misguided habits. The concept of family has always been the loose thread that held these messy lives together, as if a Sunday meal or a game of cards could keep these characters from drifting, separately, out to sea. But the recklessness of last season frayed their already weakened ties, and this season everyone seems to be on their own, and they can't rely on traditions or their place in the hierarchy to pull them through. These aren't exactly highly adaptive, flexible characters, after all, and creator David Chase takes pains to demonstrate just how far off the mark lives can drift when they're guided by haphazard, self-serving choices.

With Tony staying at his deceased mother's house and Meadow away at college, Carmela and A.J. are alone together in the house. Like Tony, Carmela turns to old tricks to sustain her relationship with A.J., cooking up formal family meals even though there are only two of them, pushing A.J. to have the kind of conversation that will soothe her into feeling that all is well with them, and offering the kind of forced affection that turns to rage on a dime. When she inquires about whether he completed his chores, at first she ignores his snottiness and cajoles him with affected sweetness, singing, "It's so nice to have a man around the house."

"You should've thought of that before," A.J. mumbles, and Carmela quickly abandons sweetness for outrage. While on the surface A.J. is acting like "an asshole" (as Carmela reports to Tony), he really just can't, like most teenagers, tolerate these transparent attempts to force him to interact on her terms.

Without Carmela's disapproval to react against, Tony seeks out another mirror for his relationship with his relentlessly judgmental mother. Who better than Dr. Melfi (Lorraine Bracco), a woman who's been silently judging Tony for years? Of course, it's absurd that Tony considers her a reasonable option: He knows next to nothing about her, and he pays her to listen. And yet it's equally obvious why she would be appealing to him, since most of the people in his life are on his payroll, and since he seems unable to tolerate relationships that actually include another human being's thoughts or needs. So he announces his intentions to Melfi the way he'd spring a job on an underling, as if his decision is all that's needed for everything to fall into place.

More absurd than Tony's decision, of course, is the inherent dishonesty of Melfi's relationship to her client. "You know, Anthony, during therapy I never judged you or your behavior," she deadpans before letting loose a torrent of harsh assessments. To make matters even more complicated, just under her judgments, there's a groundwater of desire that she can hardly stand to acknowledge. Even in her sessions with her own therapist, which play out as a struggle for professional one-upmanship, Melfi is never honest. As Chase has deconstructed the gap between family ideals and the disappointment and ambivalence ingrained in family relationships, he also sheds light on the wide rift between what a therapist-client relationship is supposed to look like, and what that relationship actually can be.

"The Sopranos" has always played with these gaps between the control and order of formal roles and the chaos of resentment and selfishness that threatens to topple them, but somehow the reassuring framework of tradition seems less structurally sound than ever this season. Conversations between Tony and his business associates tend to begin with niceties and expressions of familiarity and respect, and more frequently end in rage, egomaniacal outbursts and lines drawn in the sand. When Christopher, as the lowest man on the totem pole, is forced to pick up the tab over and over again, Tony tells him it signals his respect for those above him. The truth, of course, is that Christopher doesn't respect these people, and no amount of dues paying will change that.

Meanwhile, Adriana (Drea de Matteo), Christopher's fiancée, attempts to play the devoted and supportive partner while continuing to report on the family's business as an FBI informant. There's no real escape from this trap for Adriana, and despite the eerie ease with which she transitions between serving drinks to Tony or ironing Christopher's shirt to ratting them out to the female agent in charge of her case, Adriana has more compassion and heart than most of the other characters, and we sympathize with her impossible position accordingly. Like the others, though, she has no idea how to talk to Christopher or the mob wives about what she's going through. Like Tony turning to Dr. Melfi for love, Adriana ends up treating the FBI agent, the only person in her life with whom she's communicating honestly, like a trusted friend.

Roles in the Soprano clan are further strained by the return of Feech La Mana (Robert Loggia) and Tony Bludnetto (Steve Buscemi), former mob associates who were incarcerated in the '80s and recently released. Feech quickly asserts his interest in "getting back into the game," and though he appears to be a wild card, Tony hesitantly agrees. In contrast, Tony B., Tony's cousin and close friend, tells Tony he wants to work a straight job and continue his training to become a massage therapist. Tony says that he respects this decision, but he still can't keep himself from pitying Tony B. for making an honest living at a blue-collar job. Adding to the strain, Tony B. tries to pick up his friendship with Tony where it left off, and ends up joking around in ways that Tony feels are disrespectful. One senses that, as the boss, Tony has lost his sense of humor and genuine connection to others, and although he tries, awkwardly, to keep his rapport with Tony B. alive, once again, Tony can't tolerate the two-way street that real relationships demand. Tony B. recognizes this fatal flaw first, and seems resigned to fail at the impossible task of maintaining a relationship with someone who requires deferential behavior.

This has always been Tony's struggle: maintaining relationships from his spot high on the throne, when everyone from his kids to his cronies are wary of his friendliness, since he could turn on them without warning. As much as Tony desires real connection with others and craves honesty from them, he reacts violently against any hint of the truth, and has so little patience with anything but pandering that the impossibility of any real love in his life is painfully clear. At one point, Carmela tells Tony that he has no friends, only flunkies who laugh way too loud at his stupid jokes. Later, in a creepy slow-motion scene, when Tony gazes out at the faces of his inner circle, laughing loudly in unison at a mediocre joke, his loneliness is palpable.

As unstable and under siege as the business is and as lost as most of the characters are this season, Tony and Carmela seem to be faring particularly badly without the reassurances of family to keep them on course. After all, no matter how terrible Tony and Carmela's marriage was, they matched somehow, from their fiercely protective urges to their solidarity against the rest of the world. Despite trying circumstances, their compatibility offered hope that their partnership would somehow save them, all they needed was just a little communication and mutual understanding. Easier said than done, of course -- Chase's characters aren't exactly great communicators and rarely see past their own needs. But when Tony and Carmela's marriage evaporated, some essential strain of hope vanished with it.

So the landscape where we find these characters is far more desolate and grim than any we've seen before. No longer finding safety in their old roles, Carmela and Tony and Christopher and Adriana and the others stumble into uncharted territory with few intimate friends or heartfelt principles to guide them. Their relationships are littered with lies and confusion; their old tricks are powerless to deliver them from the kind of isolation that inevitably leads to self-destruction. As rich and alive as these characters are to us, though, the real genius of David Chase is that, instead of pounding us over the head with on-the-nose dialogue and clear-cut scenes that ring with the impending doom of, say, an FBI crackdown or an explosive fight that will tear the family to shreds, these characters' lives unravel just as real lives do, slowly and eerily, in both violent and barely discernible ways. "I think there should be visuals on a show, some sense of mystery to it, connections that don't add up," Chase recently told the New York Times. "I think there should be dreams and music and dead air and stuff that goes nowhere. There should be, God forgive me, a little bit of poetry."

This poetry is, of course, what weaves these dismal narratives together. The first episode's image of Tony sitting alone in a lawn chair with a rifle in his lap, waiting for the black bear to come back, inspires both pity and affection, and reflects the absurdity and delusion of Tony's adherence to his role. The shot captures volumes more than dialogue ever could: This is how Tony shows his love, this is how he soothes himself, this is where he feels comfortable and needed, as misguided as his efforts might be. This is the patriarch charged with a ridiculous task, one part courageous protector, one part clown.

Once again, "The Sopranos" makes other dramas look like clever puppet shows by comparison. Through lyrical digressions, rich images and a dismaying clutter of missed connections, David Chase dredges up the thinly veiled chaos of family life and the melancholy of clinging to old roles that no longer fit.

Shares