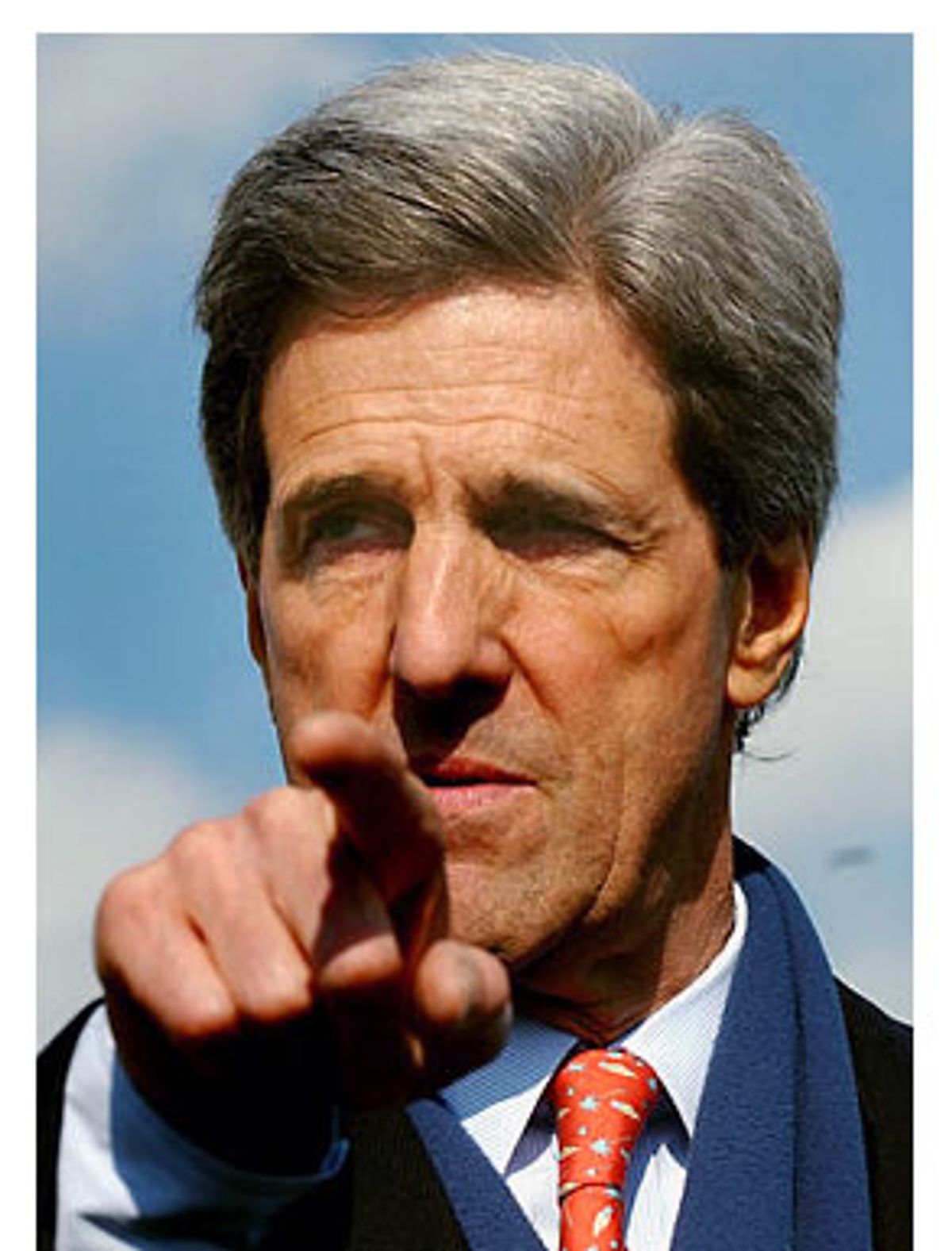

John Kerry considers himself a fighter. Don't take my word for it, or even the testimony of his "band of brothers" from Vietnam. Few presidential candidates have ever touted their own battling spirit as freely as the Democrats' nominee to-be.

"I am a fighter," Kerry pronounced during his Super Tuesday victory speech. "And for more than 30 years I've been on the battle lines, on the front lines of the struggle for fairness and for mainstream American values." It was hardly the first time he has made such a claim. "I am a fighter," Kerry said during his Iowa victory speech in January. "I'm here to win -- not for me, but for America." In February, Kerry tested a variation of the theme: "I am a fighter, and I'm ready to fight back." And of course Kerry has three words for Republicans who want to debate defense policy. All together now: Bring ... it ... on.

Sooner or later, however, candidates must stop talking about fighting, and simply enter the fray. Election Day may be eight months away, but now that the Bush campaign has rolled out its first ad blitz, that time is now. With negative ads aimed at Kerry on the way, he will certainly have to defend himself. But there's more to fighting than self-defense. To win, Kerry also needs to go on the offensive. So let's accept Kerry's word that he is one combative politician, and ask: Exactly how should John Kerry battle George W. Bush?

Many Democrats whose memories extend to 1988 would begin by saying the senator must respond forcefully to GOP attacks. That, of course, was the subtext of Kerry's primary-season fighter talk. If you vote for me, Kerry was implying, I will not campaign like the last Massachusetts Democrat who ran for president against a Bush.

Indeed, when Michael Dukakis failed to respond to George Bush's constant allegations in 1988 that he was soft on crime and unpatriotic, and let Bush use "liberal" as a political epithet, it didn't just enable Bush to wipe out a deficit in the polls. The outcome of the race established the value of attack politics for future GOP strategists.

"The Republicans really only know one way to run a close campaign," says Dan Payne, a Boston-area Democratic media consultant who has crafted ads for both Dukakis and Kerry. "That doesn't mean it will work, but they'll keep trying."

True, Bush's first three television ads are mild-mannered spots meant to restore his tarnished image. But Republican National Committee chairman Ed Gillespie began GOP testing of attacks on Kerry in February by calling him a "Massachusetts liberal" and reminded voters that Kerry served as Dukakis' lieutenant governor for two years. The phrase got little traction, though, and Kerry's war-hero status presents problems the GOP did not have 16 years ago.

"People are not going to look at Sen. Kerry and see Gov. Dukakis," says Mike Feldman, a Democratic consultant and member of Al Gore's campaign in 2000. "That playbook may have worked in 1988, but it's not going to work in 2004."

Indeed, George W. Bush himself was apparently displeased with the idea of simply calling Kerry "liberal." Bush, it seems, wants attacks on Kerry that link the L-word to specific issues. If so, he is showing a keen grasp of the dynamics of campaign attacks. (It is an area of family expertise, after all.) George Bush's 1988 attacks worked not simply because he repeatedly used "liberal" as an epithet, but because the Bush campaign also attacked Dukakis on issues where conservatives had long tried to stigmatize liberals. The disgraceful Willie Horton ads, for instance, fed the soft-on-crime stereotype that was more prominent in the 1980s.

It worked, too: According to the CBS/New York Times poll, 27 percent of registered voters in May 1988 considered Dukakis a liberal. By October, that number had risen to 42 percent. Among those who said the label mattered, three-quarters claimed it made them less likely to vote for Dukakis.

This year's RNC thus retooled its attacks to include 2004 issues, claiming Kerry was weak on defense because he had apparently voted against numerous weapons systems. In a different vein, Bush has begun claiming Kerry has flip-flopped on taxes, NAFTA, the Patriot Act and Iraq. This will be an ongoing theme, as Team Bush attempts to pin a supposed character flaw on Kerry early in the campaign, like it did in 2000 by claiming Al Gore was prone to exaggeration.

With this in mind, how effectively is the self-proclaimed fighter actually fighting back? The early evidence suggests mixed results. Kerry's best rhetorical punch came in the Los Angeles debate on Feb. 26, when he described his evolving position on Iraq by saying, "I do not regret my vote. I regret that we have a president of the United States who misled America and broke every promise he made to the United States Congress." It's a bold line that keeps Kerry away from his sometimes defensive and tedious habit of answering questions by justifying his Senate votes. Often, presidential politics is like a junior-high school argument: You can impress more people with a snappy comeback than drawn-out reasoning.

Kerry has struggled more to defend his defense votes, usually saying such charges are an affront to his patriotism. This confuses the issue a bit. Yes, the GOP has questioned Kerry's patriotism -- but mostly by referencing Kerry's anti-Vietnam protesting. In this case, Kerry should probably just say he's opposed to wasting taxpayer money on bad weapons systems, and perhaps mention that then-Defense Secretary Dick Cheney boasted of budget cuts during the same time period.

Still, most of Kerry's counterpunching so far has naturally revolved around the L-word. Kerry has repeatedly insisted that rather than being a liberal, he has "mainstream values" while Bush is the "extremist" in this race. In the New York debate on Feb. 29, he told an insistent Elisabeth Bumiller it was "ridiculous" to call him a liberal based on the National Journal's limited voting-record data -- a far more assertive response than the Dukakis campaign ever devised, and one that some Democratic observers welcomed.

"You don't want to pussyfoot around the word or pretend nobody ever made the criticism," says Ruy Teixeira, political analyst and coauthor of "The Emerging Democratic Majority." As a deficit hawk who supported the 1996 welfare reform bill and is essentially a free-trader, Kerry has a considerably more moderate record than many believe, anyway.

Kerry's repeated use of the word "mainstream" also suggests his campaign has been studying the rhetoric of 1988, since it's the very term George Bush used to describe himself that year. "I am not a big L-word candidate," Bush proclaimed just before the 1988 election. "I am more in tune with the mainstream of the United States of America." To be sure, lefties with their own pugilistic streaks would doubtless prefer if a Democrat embraced the term "liberal," but Kerry will have to hope that in 2004, the left really is prepared to vote pragmatically.

Then again, the words "mainstream" and "extremist" are not by themselves magic bullets, any more than "liberal" is. Kerry's self-identification as "mainstream" will work best when tied to a forceful critique of Bush. That's why, in 2004, being able to fend off GOP attacks is only, well, half the battle. Putting Bush on the defensive is the other half.

"I think an offensive strategy is called for," says Teixeira, adding the Democrats should "not just be talking about Kerry's record, but deliberately typecasting Bush and the people around him as being in many ways extremists." Fortunately for Kerry, this administration offers Kerry what military planners call a target-rich environment.

Take civil liberties. "Mentioning John Ashcroft always gets a big round of applause whenever any Democrat attacks him for anything," says Payne, "because he's seen as the Sherpa of the Bush administration, helping them get to the very top of the right-wing mountain." Yes, those were Democrats clapping during the primaries. But the administration's attempt to regulate civil society upsets libertarian-minded voters; independents are more strongly opposed to Bush's proposed gay marriage ban than Democrats. "These people are not looking for more direction in their lives," notes Payne. "They're looking for less." Using the issue to frame Bush as an extremist could help Kerry precisely among the swing voters he must court.

Kerry should also remember that Republicans -- whether intentionally or through a habitual reflex -- usually attack in areas where they themselves have vulnerabilities. Bush started claiming Kerry flip-flopped at the same moment Bush reversed his 2000 position on gay marriage. It's also Bush who has performed the true flip-flop on trade, with his made-in-West Virginia steel tariffs. And when Ed Gillespie says the Democrats plan to run "the dirtiest campaign in modern presidential politics," he's really just signaling his own intentions, while trying to insulate his party from one-way criticism on the subject.

Still, the Democrats have had issues to run on before, without finding the right way to frame them. "It's one thing to criticize Bush constantly for all the bad things he does," says Teixeira, but "it's a little bit trickier to get that across to people thematically. But that would be a good thing to do if they could do it." Kerry's best recent thematic attack may be his claim that Bush is running "the biggest say-one-thing, do-another administration in the history of our country." The language needs streamlining, but the idea is right: A general criticism that applies to many issues and takes aim at Bush's drooping credibility.

But if Kerry still needs to sharpen his rhetoric, the good news for Democrats is that his political career has largely been one long fight to win over moderates and swing voters -- "mainstream" voters, if you will. Massachusetts certainly has well-known liberal pockets (Cambridge, Brookline and Newton, the Northampton-Amherst axis), but much of the state's population consists of social conservatives, often Catholics, who are willing to vote for either ticket.

Moreover, Kerry has often reached these voters with not just words, but cultural symbolism that may resonate in 2004. During his first Senate race, in 1984, a group of Vietnam-veteran supporters -- the self-styled "Dog Hunters" -- helped erase Kerry's elitist image. In his toughest reelection campaign, against popular then-governor William Weld in 1996, Kerry made preserving veterans' benefits a central part of his message, just as he has this year. Kerry's support of firefighters after a fatal blaze in Worcester in 1999 helped solidify his connection with them; now yellow-and-black clad Firefighters for Kerry are a familiar campaign presence. (Kerry himself didn't need to criticize the 9/11 imagery in Bush's new ads; firefighters did it for him.) With police supporters joining the fold, Kerry has the visible backing of three groups that are post-9/11 symbols of toughness and courage -- and do not represent cultural liberalism.

That's one reason Kerry fared well with less affluent voters and Catholics in the primaries. And Catholics are not just any demographic group; they comprise a large chunk of the Midwestern swing voters Democrats covet. When Bush successfully cast Dukakis as a liberal in 1988, Dukakis' support among Catholics dropped from 55 percent in July to 40 percent by the election, and he suffered narrow losses in classic battlegrounds like Illinois, Pennsylvania and Missouri. George W. Bush beat Al Gore by 5 points among Catholics in 2000. But if Kerry can win among these voters, he can win the election.

Here Kerry has one further advantage: He is Catholic, if not especially public about his beliefs. That may change. Recently he has been opening up to voters a little about his religious feelings and altar-boy background. Should he continue to do so, pundits may smirk. But in 2004, Kerry will need every weapon at his disposal; that's politics. Ask William Weld, who recently said Bush should expect "man-to-man combat."

So is John Kerry really a fighter? Even his opponents think so.

Shares