Five hundred and thirty-seven votes.

Assume for a moment that all the votes were counted in Florida four years ago. Assume that the punch-card voting machines never malfunctioned. Assume that a badly designed butterfly ballot didn’t cause thousands of Democrats to vote for Pat Buchanan by mistake. Assume that a highway patrol roadblock didn’t scare off black voters, and that all of the black voters who made it to their polling places actually got to vote.

Assume that Katherine Harris and the Supreme Court Five and all of those angry white men with the “Sore-Loserman” bumper stickers were actually right about stopping the recount.

Assume all of that — give the Republicans the benefit of every conceivable doubt — and it still comes down to this: In an election in which 5.9 million Floridians went to the polls, the official margin of victory — the one Katherine Harris certified, the one you’ll find in the history books, the one that put George Bush and Dick Cheney in the White House, the one that wrought massive tax cuts, huge budget deficits, a war on Iraq, a slew of extremist judges, an attorney general named John Ashcroft, and a culture war over gay marriage — that margin of victory was 537 votes.

“If you throw out enough votes, you can call it a nail-biter,” says U.S. Rep. Kendrick Meek, D-Fla., who led a major African-American voter turnout effort in 2000 and is pushing hard for Sen. John Kerry this time around. “But if George W. Bush keeps being George W. Bush, I’m not expecting it to be a nail-biter this time around.”

Voters in Florida go to the polls Tuesday for the state’s Democratic presidential primary. But with the outcome of that race a foregone conclusion, and with the Bush-Cheney campaign flooding Florida’s airwaves with controversial new TV commercials, all eyes are on November. And for the moment, at least, Democrats are feeling cautiously optimistic about their presidential prospects in a state they believe they won four years ago.

There may be good reason for that. While Bush began the 2000 race with a double-digit lead over Vice President Al Gore in Florida, a poll released over the weekend has the president trailing Kerry in the state by six percentage points. A majority of Florida voters disapprove of the way Bush is handling the economy; a plurality believes he exaggerated intelligence to build support for the invasion of Iraq; and, by a wide margin, voters in this senior-heavy state trust Kerry more than Bush when it comes to protecting Medicare and Social Security.

Many of those who supported Bush in 2000 seem ambivalent and unenthusiastic about him today, while Floridians who voted against Bush four years ago — particularly African-Americans and older voters in Palm Beach County who believe they were disenfranchised — are enraged and inspired to oust him from office now.

“We understand that the deck is stacked against us, and it’s just wrong,” said the Rev. Griffin Davis, pastor of the predominately black Hilltop Baptist Church in the Palm Beach County city of Riviera Beach. “But God ain’t pleased with what’s happening in this country, and it’s going to keep on happening until Bush is out of there.”

And among Democrats, Davis may be the rule, not the exception. Shirish Dáte, the capitol bureau chief for the Palm Beach Post, said he has never seen Florida’s Democrats as “fired up” as they are today. “You could run Mickey Mouse against Bush right now,” he said, “and a lot of Democrats would turn out to vote.”

Drive through the city of Palm Beach, and you might think that Walt Disney himself slid over from Orlando to open a theme park called “Prosperityland.” The city is rich-person perfect, all sun-kissed and sanitized without a palm frond out of place.

It’s hard to imagine that there’s anger seething just under the shiny surface of this county, but there is. Thousands of voters were disenfranchised by a confusing butterfly ballot here in 2000, and they’re every bit as upset about it today as they were four years ago. “People are still furious, and the anger and the venom has not diminished,” says Tony Fransetta, president of the Florida Alliance for Retired Americans, an umbrella organization for advocacy groups representing more than 150,000 residents. “Seniors in Palm Beach County will tell you in a heartbeat that George Bush stole the election.”

You can count Jewel Littenberg in that group. Littenberg is a politically active senior citizen from West Palm Beach, the only slightly less tony community just across the bridge from Palm Beach itself. Littenberg lobbies for better care for seniors, and she hosts a senior-focused show on the local cable channel. She’s smart and articulate and she’s got all her wits about her. But almost three and a half years out from 2000, Littenberg says she has “absolutely no idea” who she voted for in that ill-fated election.

Like thousands of other Palm Beach County residents, Littenberg fell victim to a ballot that put the chad to punch for Reform Party candidate Pat Buchanan right where many voters would logically have punched a hole for Al Gore. Post-election analyses showed that voters in reliably Democratic parts of Palm Beach County cast votes for Buchanan in inexplicably large numbers; a Palm Beach Post study found that Gore lost more than 6,600 votes in the county — or more than 10 times Bush’s official margin of victory — because voters selected both Buchanan and Gore.

“It was a poorly designed ballot, just terrible,” Littenberg said last week. “All I know is that the card absolutely did not fit and the holes did not line up. I don’t know who I voted for. To this day, I don’t know.”

What Littenberg does know is that she’ll channel her frustration from 2000 into action in 2004. She is mortified by the notion that she might have helped elect George W. Bush, and she was insulted when Katherine Harris and others suggested that any problems with the ballot were the result of voter error. “Does it make me angry? Yes, it makes me angry,” Littenberg said. “Bush became president on a lie,” she said, and his administration has lied repeatedly since then. “So much of what he has said he was going to do he hasn’t done, and so much of what he has said was there wasn’t there.”

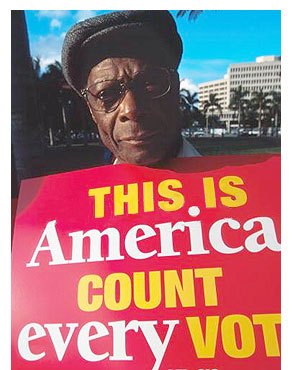

Littenberg isn’t alone, either in her feeling of disenfranchisement or her determination to do something about it. According to the Miami Herald, more than 170,000 Florida voters “ruined” their presidential ballots by either voting for more than one candidate or by not marking their ballot in a way that could be read by ballot-counting machines. In a June 2001 report, the U.S. Civil Rights Commission found that disenfranchisement “fell most harshly on the shoulders of African-American voters.” One newspaper review of voting records shows that nearly 9 percent of the votes cast in majority-black precincts went uncounted in Florida in 2000, compared to “just” 3 percent of the votes statewide. The Civil Rights Commission cited estimates that black voters were nearly 10 times more likely than whites to have their ballots rejected.

And those analyses addressed only those ballots that were actually cast. Many African-Americans were denied the right to vote at all, either through intimidation delivered by a highway patrol checkpoint that just happened to be set up near a polling precinct in Leon County, or through policies that incorrectly purged many African-Americans from the voting rolls and then denied them the chance to correct the errors on Election Day.

“That election was a coup,” says Davis, the 64-year-old pastor at Hilltop Baptist. “It was unspeakable, OK? It was a power thing, a political thing, a hostile takeover.”

Rep. Meek, whose campaign dramatically increased turnout among African-Americans in 2000 only to see so many of their votes go uncounted, said last week that he expects black voters to show up at the polls with a passion in November. “George Bush loves black people in his TV commercials,” Meek said. But he said it is Bush’s policies — particularly on the economy, jobs, healthcare and possibly the crisis in Haiti — and not his TV spots that will drive the black vote.

Exit polls showed that black voters preferred Al Gore over George Bush by a margin of 93-7 percent in 2000. Activists are working hard to ensure that black voters turn out in large numbers this year; a coalition of civic and social-action groups have set a goal of registering 2 million new black voters for November. Among their target states: Florida.

Some observers are skeptical that Florida Democrats can muster the same extraordinary black turnout in 2004 that they enjoyed in 2000. University of South Florida professor Susan MacManus notes that turnout among African-Americans fell sharply from 2000 to 2002, despite the fact that Democratic National Committee chairman Terry McAuliffe attempted to turn Gov. Jeb Bush’s reelection race into a referendum on George W. Bush and the 2000 vote.

And Dáte, the Palm Beach Post bureau chief, said that African-American voters may be less motivated to vote this time around because one of the factors that drove them to the polls in 2000 — anger over Jeb Bush’s abolition of affirmative action in 1999 — is a more distant memory now.

Both MacManus and Dáte expressed concern that feelings of disenfranchisement in the past could leave African-Americans feeling that any attempt to vote now would be futile. Meek is not convinced. Every day, he said, George W. Bush “reminds African-Americans why they should wake up early to vote against him.”

It’s almost impossible to overstate the importance of Florida in 2004. With 27 Electoral College votes — two more than it had in 2000, and 10 percent of the total needed to win — Florida is the fourth-biggest prize in the presidential race. But it’s bigger than that, really. Barring an unexpected landslide one way or the other, the only states with more Electoral College votes than Florida are already spoken for. California and New York are predictably Democratic; Texas is solidly Republican. That means Florida will likely be the biggest state in play.

“Florida is a must-have state, and both parties have admitted so,” says MacManus, a leading analyst on Florida politics. “And it’s just as much about the election in 2000 as it is about the election in 2004. Both parties want to prove that they won Florida in 2000, and they want to lock in all the new voters who have registered here since then.”

History suggests that a Democrat can win without Florida; if Al Gore had just carried his home state of Tennessee, he would have taken the White House no matter what the Supreme Court said. But so long as Kerry holds on to California and New York, which together promise nearly a third of the Electoral College votes needed for victory, it’s hard to see how Bush can win the reelection without the Sunshine State. The last Republican to win the presidency without Florida was Calvin Coolidge in 1924.

The Electoral College math explains the attention being lavished on Florida by the Bush and Kerry campaigns. Bush has visited Florida 19 times already, and not just to visit his brother. Bush’s policies on Cuba and his desperate determination to pass a Medicare prescription drug benefit suggest that Karl Rove is paying close attention to voting blocs here, and Bush-Cheney media buys last week prove it; the campaign appears to have spent nearly a million dollars on TV in Florida already.

Kerry can’t match Bush in time or money, but he’s trying. By the time Sen. John Edwards announced his withdrawal from the Democratic race last week, Kerry was already in Orlando, stumping for votes among the swing voters who live along the I-4 corridor. Kerry said Florida will be a “critical battleground” in November — so much so that he returned to the state Monday for two more days of campaigning.

Both Republicans and Democrats are spending time trying to peel off Floridians typically in the others’ camp. The Republicans have worked with Haitian-Americans in the hopes of finding some kind of toehold among blacks, and they’re courting the traditionally Democratic Jewish vote in Florida as well.

Steven Abrams, the Republican mayor of Boca Raton, said the attacks of Sept. 11 and the absence of Joe Lieberman on the Democratic ticket give Republicans an opening with Jewish voters, who he said comprise about 7 percent of Florida’s voting population. Kerry has a strong record on Jewish issues; after Kerry met privately with Jewish leaders in New York last month, the head of the Anti-Defamation League told the New York Daily News that there’s “no significant gap” between Bush and Kerry on Israel. Abrams doesn’t buy it. Given Bush’s almost unequivocal support for the actions of hard-liner Ariel Sharon, it would be hard for anyone to be as solidly pro-Israel as the president has been. And the Republicans are plainly ready to attack Kerry for “flip-flopping” on the Middle East; Abrams noted that Kerry initially seemed to criticize Israel’s construction of a security fence, then seemed to back off from that criticism during his meeting with Jewish leaders.

Kerry is trying to pick off fiscal conservatives in Florida, highlighting the massive budget deficits that have appeared on Bush’s watch, and he’s working to appeal to military voters by citing his own war record and calling on military-friendly surrogates like former Georgia Sen. Max Cleland.

Kerry could dramatically improve his fortunes in Florida with a savvy vice-presidential pick. With stories surfacing about the apparently chilly relationship between the two men, the bloom may be off the Kerry-Edwards rose. If Kerry is serious about contending in Florida, he may think long and hard about Sen. Bob Graham, the tremendously popular Floridian who made a brief run at the presidency himself and who has made it clear that he’d accept a spot on the ticket if it is offered.

While a Miami Herald/St. Petersburg Times poll released over the weekend showed that Kerry was doing well enough in Florida that the presence of Graham or junior Sen. Bill Nelson on the ticket wouldn’t help him much, not everyone agrees. Dáte, who has just completed a biography of Graham, said that Florida is so important to Kerry that Graham could be a worthwhile addition to the ticket “even if all he does” in the campaign is travel back and forth “from Pensacola to Key West.”

Even without Graham, however, Kerry seems to enjoy the enthusiasm edge over Bush in Florida — at least for now. Kerry is riding the momentum of primary victories around the country; the Bush-Cheney team has just barely cracked open its massive war chest for campaign commercials. Once Karl Rove starts spending the millions he’s got in reserve — and if Ralph Nader’s campaign picks up any steam at all — Kerry could find himself in real trouble in Florida. But still, around the state today, voters appear to feel a sense of ambivalence about the president, and that’s got to work in Kerry’s favor.

You hear it wherever Floridians gather, even among his supporters. There’s a big flea market set up in the parking lot outside a dog track in the Broward County community of Hallandale Beach. On a warm weekday afternoon, hundreds of seniors wander around and pick through the bargains: bottles of knock-off cologne, slightly used golf balls, and a lot of underwear that might be fashionable among women a decade or so beyond a certain age. Perry and Paulyne Golden are making a day of it. He’s 80, she’s 79.

Although they call themselves “Truman Democrats,” the Goldens are the kind of voters who ought to be enthusiastic about George W. Bush. They’re military people — Perry Golden served in World War II, and their son just left the service and took a job with the Department of Homeland Security. Al Gore “nauseated” the Goldens each time they saw him on TV, Paulyne says; he was a “typical free-spending ultra-liberal,” Perry says, and he “scared” them. “John Kerry scares us, too,” Perry says. Their worry: When Kerry says he’ll roll back tax cuts for the wealthy, he just might mean people like them.

The Goldens voted for Bush in 2000. But ask them who will get their votes in 2004, and they hesitate. After a long pause, Perry says: “Bush, reluctantly.” The Goldens like the president’s tax cuts, and they think he’s doing about as well as anybody could on homeland security. But they’re unhappy with his hard-right views on issues like abortion, and they wish he presented himself better. “He comes across as a very poor communicator,” Perry says. “He’s not a Reagan. He’s not even a Clinton.”

Voters at a local candidates’ debate in western Broward County expressed a similar lack of enthusiasm about the president last week. “I like having lower taxes,” says Republican Debby Beck, a Parkland City commissioner. Beck voted for Bush in 2000, but like Perry Golden she hesitates when asked how she’ll vote this time around. She ultimately says that she’ll support the president, but she seems far from enthusiastic. Beck volunteers that she is “disappointed” by Bush’s support for a constitutional amendment banning gay marriage. “I think civil unions should be available to people who need that status and the benefits that come with it,” she says.

Voters like Beck and the Goldens illustrate a key point about Florida politics; despite the white-hot partisanship of 2000, Florida is a centrist state. Because the state has an unusually diverse group of voting blocs — Florida includes large populations of Jews, African-Americans, Cubans, Haitian-Americans, military families and retirees, most all of whom have come here from somewhere else — elections in Florida necessarily turn on the voters in the middle. “We’re not ultraconservative or ultraliberal, and what’s concerning to both parties is when national leaders get too far on either end of the spectrum,” says MacManus, the University of South Florida professor.

That presents problems for both Bush and Kerry. While Bush and Gore both ran as moderates, it will be harder for either of the current candidates to portray themselves as centrists in 2004. The Republicans have already tagged Kerry as a Massachusetts liberal with a voting record to match, and Bush’s need to shore up his Christian conservative base makes it hard for him to appeal to more socially moderate voters at the same time.

Christine Hunschofsky, 34, is an independent voter and self-described “soccer mom” from western Broward County, and she underscores the problem Bush faces after swinging so far to the right. Hunschofsky said she could have voted either way in 2000. She ultimately made her decision by tossing a coin, and the winner was Al Gore. This time around, she can’t even conceive of voting for Bush.

Candidate Bush appealed to Hunschofsky in 2000 because he surrounded himself with people she trusted, people like Secretary of State Colin Powell. “He sold himself as a manager, someone who would listen to both sides,” Hunschofsky said. But President Bush has “frozen out” moderate voices like Powell’s, she added. “Bush is a likable guy, but his politics seem so one-sided. There’s no way I could vote for him now.”

There are surely hundreds of thousands of die-hard Bush supporters throughout Florida today, people who see the president as a God-fearing man of his word who has made the country stronger and safer and put it on a path to economic prosperity. Many of them live in the northern part of Florida — the part that is, paradoxically, most “Southern” — a region dominated by military bases, retired military families and the sort of born-again social conservatives who control politics through much of the South.

But even among Florida’s most conservative voters, Bush is being subjected to some of the same sort of second-guessing that bedeviled his father. While social conservatives seem mollified now by Bush’s signing of the ban on late-term abortions, his recess appointments of right-wing judges and his support for a constitutional amendment outlawing gay marriage, fiscal conservatives have raised concerns about the spending increases and deficits created by a Republican president and a Republican Congress.

The tension is apparently getting under the president’s skin. According to a recent report in the Hill, Bush lost his composure during a recent telephone conversation when Rep. Tom Feeney, a conservative Republican congressman from central Florida, told the president that he couldn’t support his Medicare bill because he came to Washington to cut entitlements, not raise them. According to the Hill, Bush shot back, “Me too, pal,” then hung up on Feeney.

It wasn’t the first time a Florida-related phone call got Bush’s goat; remember the heated exchange that occurred when Gore “un-conceded” the race on that fateful night four years ago and had to tell Bush not to get “snippy” with him. If Kerry and the Democrats have their way, Bush will have one more bad call from Florida eight months from now.