"Are you in India now?"

I silently held the phone for a moment, not knowing what to say. I am Salon's customer support representative. The customer had put my name and my title together and asked the logical, if awkward, question.

"No, I'm in San Francisco," I answered tentatively.

"Same difference," he blustered.

My gig at Salon entails much e-mailing and a bit of phoning, helping people subscribe and renew and retrieve lost passwords, and copying and pasting paragraphs from the FAQ. In other words, I work from a cubicle in San Francisco, but I could easily telecommute from Omaha -- or Bombay. A few subscribers have tentatively mentioned that I have a beautiful name, or that they loved "Bend It Like Beckham," but this was the first caller to call me out on the absurdity of my position. An American-born Indian doing call-center work in California?

After that, I heard a story from my equally brown sister. Nandini related that, upon hearing her loud American voice in a Bangalore pub, a call-center representative had complimented her accent and offered her a job. Even better: The headhunter didn't give up until my cousin spoke up, informing the interloper that he himself answered phones for Dell and could get Nandini a far better gig than one at some no-name Indian firm.

Given that the universe already believes that I belong in an Indian call center, I had to take the chance to visit the real thing when I visited my parents in south India this year. My parents' cousin's cousin arranged an evening visit to her call center in Bangalore.

As I entered the lobby at sunset, the polite crowd of young male jobseekers made finding a seat nearly impossible. Their gazes traveled to the rent-a-cop security desk, to the lobby's generic ATM, and to the doorway between them.

The men in that lobby yearned for that ATM. Extravagantly, ahistorically decadent salaries flow from that ATM. For its employees, who make more than teachers, more than CPAs, the firm pumps out thousand-rupee notes -- fast money, faster and more meritocratic than California gold-rush riches ever were.

The building's cubicle walls were sea green and light blue, anonymous and modern. The clip art on the walls reminded people to keep customer information confidential -- "What is said here stays here!" -- while Dennis the Menace posters encouraged productivity and teamwork. A mostly patient fellow of about 24 led Oscar from New Jersey through a DSL diagnostic procedure. My subject idly refreshed his desktop over and over. Most workers wore well-made Western clothes and laughed together between calls.

I observed their work, similar to my own. But their friendships, in this after-dark cocoon of intimacy, reminded me of nothing so much as college dorm life.

Indian colleges often don't provide the revolutionary independence of American campuses -- dorms are single-sex, and many students live at home or with relatives. But college life in the U.S. is all about late nights with your peers. Aside from diplomas, the profound benefits of college in the United States are tacit lessons: how to make mature friendships, how to think rationally, how to affect a businesslike demeanor, how to break free from your family and your past. And that's what these call-center workers are learning. In that room, they make fast friends, flirt, try out new clothes and identities, earn easy cash, and learn how to be cosmopolitan consumers.

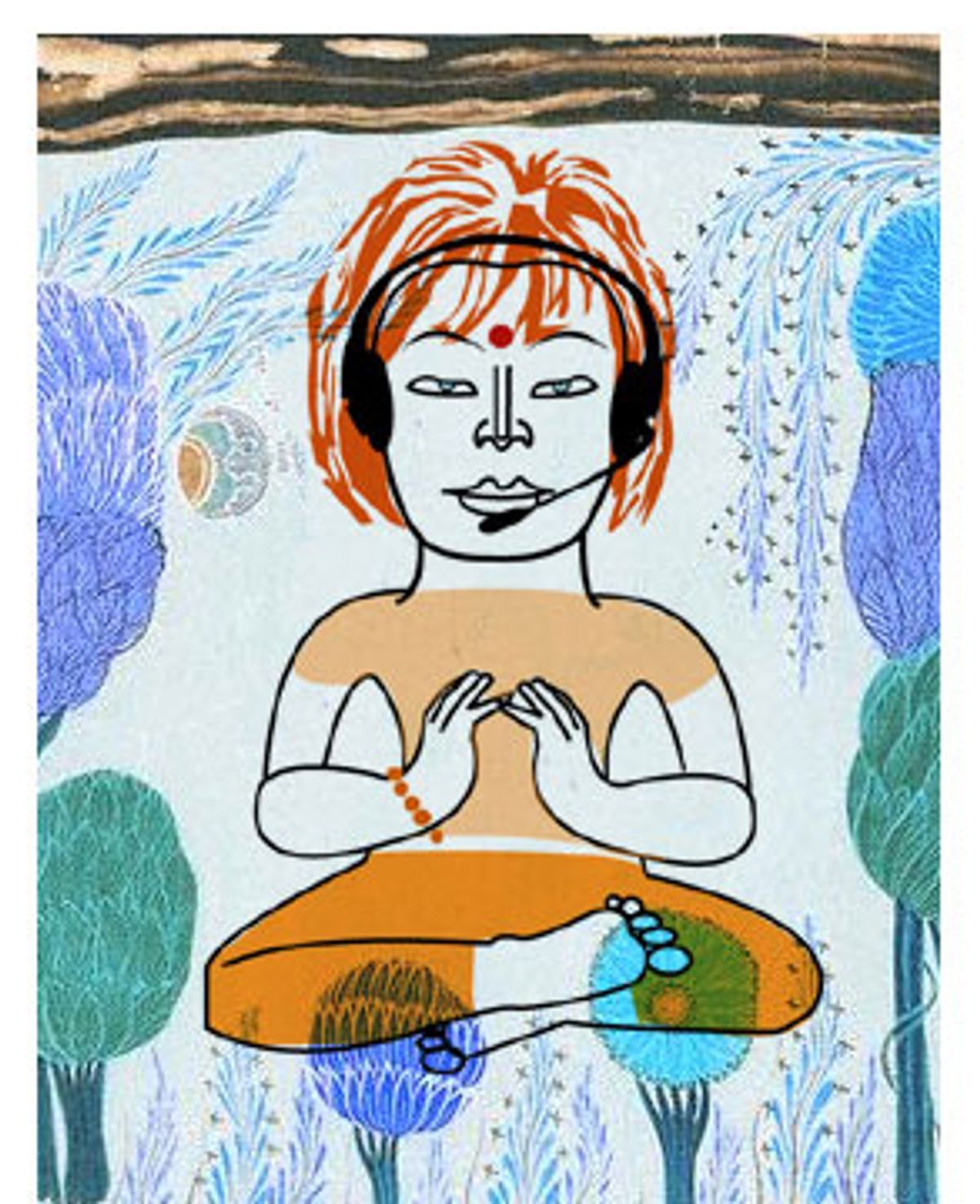

Moreover, these workers are my cousins. They are basically me in the alternate universe where my parents stayed in India instead of moving to the United States. My Indian cousins go to three-week institutes to consciously learn my birthright. They and I are two sides of the same devalued coin. I am an Indian in America, trying to relearn my heritage: Kannada, subtle and nutritious vegetarian cuisine, the Mahabharata, and a meditative frame of mind. They are Indians finding America, servicing it, learning to coddle its temperaments, learning that we value results over process.

Does mystical Eastern stoicism make us good at this job? The empathy for the conqueror that all colonial people have to learn? For me it is a job, and for them it is liberation.

At this call center, I listened to Indians who "neutralize" the Indianness in their accents, and I discovered that Indian English minus Indian eccentricities equals British. The old English joke remains: For all the oppression Britain levied on India, "at least we gave them the railroads." Fifty years after independence, the linguistic infrastructure that Britain left behind counts for something too.

I help First Worlders dispose of their income. And my cousins, riding out of the Indian rice paddies on a train that history accidentally left behind, are learning to replace me. I wince and I worry, but how can I begrudge them their good luck?

Shares