Who says there is no progress in the Middle East? The number of terror attacks in Israel has fallen dramatically over the last year or so. Now it's only every three to four weeks that Jerusalem residents face bomb blasts on their buses. Despite a recent flare-up of violence, including this week's Israeli raid in Gaza that killed 14 Palestinians, Palestinian deaths have also declined significantly, as Israeli military operations in the West Bank have become much less frequent. Even though this is probably because they are running out of targets, it still makes a difference. A few roadblocks have been lifted, a few thousand more Palestinians have been allowed to work in Israel, and things have settled down into a certain stability of misery in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.

While Palestinian society and institutions have been devastated by the violence of the last three and a half years, Israel is actually doing very nicely, thank you. The intifada has failed to break the country, even economically. It's true that Israel went into a recession during the violence, but that was also a result of the global downturn. Now growth has been restored, albeit at a lower rate than before.

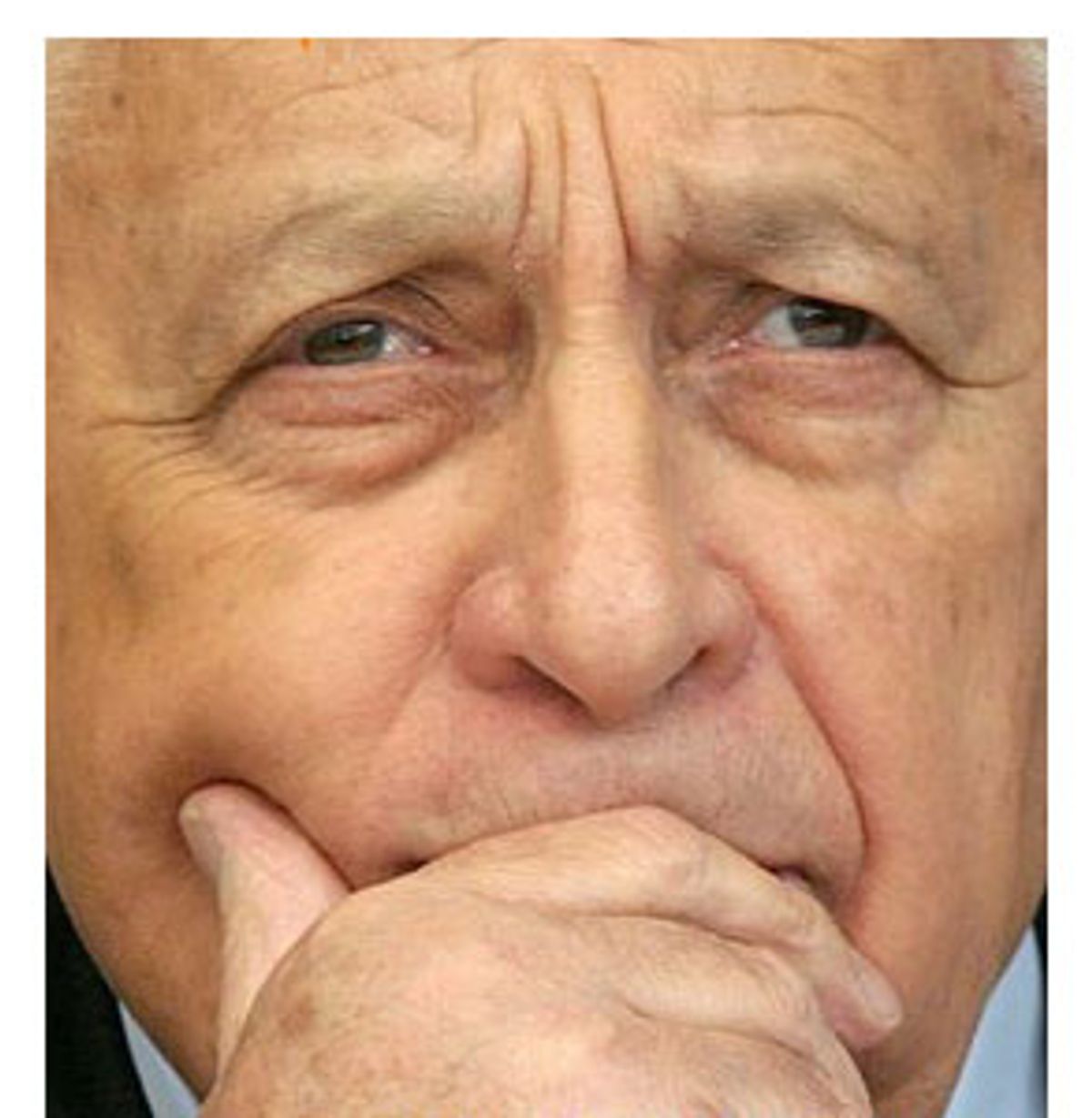

At the center of all this is Ariel Sharon, Israel's controversial prime minister, who has now been in power longer than any other Israeli leader since Yitzhak Rabin was murdered in 1995. Under fire at home over various corruption affairs with an increasingly soap-opera feel to them, Sharon seems nevertheless master of the political and diplomatic landscape. One thread runs consistently through his life: the ability to profit from other people's mistakes. Ehud Barak obliged him in that respect over three years ago and Yasser Arafat has done it ever since. He has also had the international situation and the Bush administration working for him.

Now the world may well have to come to terms with the fact that the only diplomatic solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that has any chance of being implemented may largely be dictated by Sharon. He has dealt a death blow to the international peace plan, the road map, which had all but expired anyway. By announcing his intention to withdraw from the Gaza Strip and parts of the West Bank, Sharon has thrown down a challenge to the world that it cannot ignore. Who can in good conscience oppose the dismantling of Jewish settlements, even if it is done unilaterally, simply because it is Sharon who proposes it? By now, even U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan has cautiously endorsed the idea.

In Israel and among the Palestinians, the plans have created huge confusion. Nobody knows for sure if he will actually go ahead with the evacuation and if he does, whether that would be good or bad. There is only one sector that consistently criticizes him for even voicing such thoughts: the settlers and their right-wing supporters. Their opposition is shrill and unashamedly invokes the Holocaust. Despite vows not to use violence against their own soldiers, they sound ready to make a last stand. "In 1942 the Jews in Europe also boarded the trains voluntarily because they thought they were going to be evacuated," is a typical statement made by Eran Sternberg, who is in charge of press relations for the Gaza settlements.

During a recent visit to those settlements, Sternberg tried to keep visiting journalists on a short leash, herding them in groups to meet prearranged "ordinary people" in the Gush Katif villages or in Netzarim, the most isolated of all Gaza settlements. Only one road connects it to Israel proper. Entering the road from the Israeli side is something of a mad Max experience, with soldiers milling about in the desert, settlers in bulletproof vests getting into their cars, and a concrete, barbed wire and sandbagged military position where the actual border is. The bus that services the route has been shot at and blown up. Only the lower windows are bulletproofed, so the driver advises the passengers not to stand up during the 10-minute trip. At the beginning of the intifada, Netzarim junction, where the east-west access road crosses the main north-south route through Gaza, was the scene of violent battles between Palestinians and the Israeli army. According to the Israeli human rights group B'Tselem, some 45 Palestinians have died there.

Netzarim is regarded even by many Israelis as symbolizing the particular aberration of Jewish settlements in Gaza. Some 7,000 Israelis live in heavily fortified enclaves in the strip among more than 1.2 million Palestinians. The disparities between the two communities are huge. The settlements occupy the richest agricultural lands and the most important water resources, while Palestinian Gaza is one of the most crowded and poorest places in the world: in effect, a gigantic jail surrounded by a fence. The settlers have an effect on the daily lives of the Palestinians that is disproportionate to their small number. The settlements and their access roads cut Gaza in pieces and make travel difficult, and when the Israelis close the roads for security reasons, impossible. Exchanges of fire and Israeli security measures around the settlements have reduced the surrounding areas to moonscapes. In Khan Younis in the south of the Gaza Strip, the rows of apartment buildings facing the Neveh Dekalim settlement are scarred by gun and tank fire, with gaping black holes on the outside and shrapnel patterns decorating the ceilings of living rooms.

Gaza has a particular madness to it and it lacks the strong Biblical associations of the West Bank, which is why Sharon found such support among Israelis for his plan to get out. The really amazing thing is that he may actually succeed where several Israeli prime ministers before him failed. Menachem Begin, for example, tried to palm off the strip, which on its southern end borders Egypt, to the Egyptians as part of the Camp David peace deal between the two countries. President Saddat refused, not wanting to be drawn into a Palestinian quagmire; his successor, Hosni Mubarak, is of the same mind. He has characterized Israeli attempts to enlist Egypt as a policeman as "a trap," designed to provoke a conflict between the Egyptians and the Palestinians. But even Egypt cannot afford to ignore the consequences of an Israeli withdrawal from Gaza. Cairo has hinted that it too, just like the U.S. administration, is worried about fundamentalist Muslims taking over the strip. Egypt waged a bloody internal war with its own fundamentalist insurgents in the 1990s. The Egyptians have hinted they will demand that Israel agree that Egypt be allowed to increase the number of troops it is allowed to station in the Sinai Peninsula under their 1975 peace deal.

The withdrawal plan is the subject of feverish contacts between the Israelis, the Americans, the Egyptians and the Palestinians. The Egyptian minister in charge of security affairs, Omar Suleiman, visited Arafat in his Ramallah compound and demanded, according to Palestinian sources, that he restore P.A. control in the Gaza Strip before an Israeli pullout and confront the Hamas and Islamic Jihad movements.

It would appear that the Bush administration shares some of the Egyptian worries -- and has some of its own. Three ranking Bush administration officials are in Israel this week for the second time in less than a month to sound out Sharon on the details of his plan: Assistant Secretary of State William Burns, Stephen Hadley, deputy director of the National Security Council, and Elliot Abrams, a Middle East specialist at the council. The visit follows remarks by Secretary of State Colin Powell that the administration has "many questions" about Sharon's plan. These are thought to include the extent of the withdrawal from Gaza, the question of coordination between Israel and the P.A. over the pullout and Sharon's plans for the West Bank, specifically the possibility that he may demand a trade-off for the evacuation of Gaza in the form of U.S. acquiescence to the annexation of some settlement blocs. Most of these questions, U.S. officials have implied, have arisen because of Sharon's deliberate vagueness about his intentions. The going has been so slow that a meeting between Bush and Sharon scheduled for this month has been bumped to April.

Washington is said to be particularly concerned about the possibility of the militant Hamas organization taking over the Gaza Strip, where it is very powerful. In fact, just why anyone thinks this would happen is unclear. As it is, the Palestinian Authority retains a tenuous hold on the area, while Israeli control is confined to the settlements. Handing over the settlements to the Palestinians will by all accounts make it easier, not harder, for the P.A. to impose its will on the people. Zakaria Al-Agha, a senior leader in the Fatah movement in the Gaza Strip and a P.A. official, says that once the Israelis leave it will be easier for the P.A. to exert control than it is now. "Now we cannot freely move our forces through the strip because of all the obstacles and if we act we are seen as collaborating with the Israelis," says Al-Agha. "Once they are gone it will be very clear that we are only acting in order to provide security for our own people, not the settlers."

Sheik Ahmed Yassin, Hamas' spiritual leader, was quoted this week in Israel's Ha'aretz newspaper as denying that his movement has any plans to take over control of the strip from the P.A. "We have never had the intention of taking over security responsibilities in the strip," he said. "We seek cooperation and partnership among all the Palestinian national and Islamic movements." He even held out the possibility of a temporary cessation of Hamas attacks against Israel. "With regard to Gaza, resistance may stop for a certain period of time if all Israelis [settlers and soldiers] leave Gaza, until we see what the fate of the West Bank, our refugees and Jerusalem will be."

However positive this statement may seem, it actually holds out very little chance for a longer-term cease-fire. It is very unlikely that Israel and the P.A. will resolve these issues; even if they do, it is very unlikely that Hamas will agree to the inevitable compromises this will involve. Other groups, such as the military wing of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, PFLP, have already said they will continue to attack Israelis, "wherever they are," as one of the group's leaders in Khan Younis put it. "If they leave we will follow them. We will pursue them and fight them wherever we find them." The PFLP leader said he would carry on fighting until the liberation of "the whole of Palestine." That is also the official Hamas position.

Much more than an Israeli withdrawal, the development that could move Hamas into power in Gaza is the infighting among Fatah factions in the strip, which is threatening the ability of the P.A. to exercise control. Over the last couple of weeks, a prominent journalist and senior aide to Yasser Arafat has been killed in Gaza, other journalists have been beaten up and intimidated, officials and police stations have been fired on and gun battles have raged between the factions. The background to this, according to some, is a general breakdown in law and order in the Palestinian territories, both on the West Bank and in Gaza, as a result of Israeli attacks and harsh measures which have undermined the security forces. In Gaza, however, it seems clear that the supporters of Mohammed Dahlan, the former security minister and head of the Preventive Security Service in the strip, are unhappy that he was sidelined by the P.A. leadership after he and Prime Minister Mahmoud Abbas were forced to resign last year. The background story is the ongoing struggle between the old-guard PLO leadership that came back from Tunis with Arafat after they returned from exile and the local leaders who emerged under Israeli occupation, such as Dahlan, although he too spent some time with Arafat in Tunis. Dahlan, like Mahmoud Abbas, is seen as more moderate and willing to work with the Americans and Israelis than the old-guard Arafat loyalists.

Neither Dahlan nor his opponents in the P.A. have any interest in the strip falling into the hands of Hamas. But fear that this could happen has set the alarm bells ringing in Washington. The Bush administration seems less concerned about the long-term implications for the peace process if Sharon imposes his unilateral vision than about short-term upheaval in Gaza hurting Bush's reelection chances. The last thing Bush needs is another Middle Eastern crisis. If trouble were to flare up in Gaza after an Israeli withdrawal or if the strip is in fact taken over by Hamas, this would not reflect well on the president. This explains why the Bush administration asked Sharon to postpone any pullback until after November, as reported in the Israeli daily newspaper Ma'ariv this month.

Administration officials deny this interpretation. They say that it is actually the Israelis who are insisting on moving deliberately, and point to Israel's previous experience with a unilateral withdrawal, from South Lebanon in May 2000. That withdrawal left an opening for the Hezbollah movement to keep fighting the Israelis over some unresolved issues, gave it considerable prestige as a group that forced Israel to retreat by force of arms and, in the view of some analysts, precipitated the intifada.

But if Bush fails to consider the larger consequences of Sharon's plan, in particular what he intends to do with the West Bank, he will only be postponing a later eruption. Sharon's unilateral disengagement plan may seem attractive at first sight because it offers a dismantling of some settlements, even on the West Bank, and thus decreases the number of points of friction between the two sides. But in reality the problem will only be deferred. The Palestinians will come under huge international pressure to make concessions and rein in militant groups as a result of Sharon's "disengagement" tactic. Even worse, from the Palestinian standpoint, Sharon's moves -- both pulling out of some settlements and building the fence -- may mean that Israel can ignore the Palestinian issue, without the international community intervening. With terror attacks reduced by the fence and some settlement evacuation, the problem will be seen internationally as less pressing. The Palestinians could resort to international actions to get attention, as they did in the '70s, but in the post-9/11 world that tactic seems futile.

As they run out of options, the Palestinians may indeed turn on their own leaders who have failed to deliver. According to some reports, this is exactly what both Sharon and the U.S. administration are aiming for: the unilateral moves are intended to finish off the current Palestinian leadership, in particular Yasser Arafat, once and for all. The wishful thinking in Washington and Jerusalem then is that a more amenable leadership would emerge, even though all indications point to the opposite.

These theories are regarded by most observers on the ground as so fanciful that they do not even merit contemplation. In fact, what Sharon is offering the Palestinians with his unilateral disengagement falls so short of their aspirations that continued conflict is inevitable, as the Hamas leader Sheik Yassin hinted in his comments. There are no indications whatsoever that Sharon intends to go beyond the limited withdrawals that he envisages for the West Bank, that he is willing to share Jerusalem, that he can come up with a creative solution for the refugee issue or that in general he will seriously negotiate with the Palestinians on the myriad of issues that divide the two peoples. Unilateral moves will not solve disputes over air space, water resources, taxes, border controls, and so on.

It may well be that Sharon never intended to negotiate with the Palestinians. He has always proclaimed his distrust of the other side: He was vehemently opposed to the Oslo peace accords and remains proud that he is the only Israeli prime minister since Yitzhak Shamir in the early '90s who has not shaken the hand of Arafat. When he came to power during the intifada he made negotiations impossible by insisting on periods of calm before talks could start. Often it was his own army that seemed to provoke another round of bloodletting by launching targeted assassinations just as talks seemed imminent. He has consistently targeted the institutions on the Palestinian side that could provide and back up negotiators. The security services, which did cooperate very efficiently with the Israelis in the late 1990s, were gutted. (It is true, though, that a significant number of their members have been involved in anti-Israeli acts during the intifada.) And recently he released large numbers of Palestinian prisoners to the militant Lebanese Hezbollah movement -- while he had refused to do the same in order to support the moderate Palestinian Prime Minister Mahmoud Abbas.

Whether premeditated or not, Sharon's actions since September 2000 have helped to put an end to anything that can be called a peace process. He has been able to achieve this not only through his own cunning but also because of the incredibly irresponsible behavior of the Palestinian leadership under Yasser Arafat, who is at least equally to blame for the violence. Arafat encouraged the intifada, released Hamas and Islamic Jihad bomb makers from his prisons and enabled them to recommence their suicide attacks, and is personally involved with the Fatah branch practicing the same methods, the Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades. Sharon also cleverly exploited the leeway that the 9/11 attacks gave him to counter terror and he was able to maintain a strongly positive relationship with the Bush administration. The result is that the peace process is well and truly dead.

There remains one ray of light. Even though, in all likelihood, Sharon intends to go no further than a very limited withdrawal from the West Bank, such steps have a way of creating a dynamic of their own. Once you start withdrawing it is difficult to stop, because how do you explain the difference between the territory you have already given up and the lands you are still hanging on to? The true future test, which also and perhaps especially is a challenge for the Palestinians, is to agree to share the land and its resources and to agree on all the important arrangements between states that make for good neighbors. An internationally supervised negotiation process, with the United States leading the way, is the only way to achieve that.

Shares