The Bush campaign launched its first negative attack ad on television late last week, earlier than in any presidential race in history. For an incumbent president to abandon the elevated surroundings of his White House Rose Garden so speedily reveals anxiety about an opponent ahead of or tied with him in the polls. Bush's 30-second spot portrays Sen. John Kerry as "wrong on taxes, wrong on defense." It claims that he would raise taxes by $900 billion. (A Kerry spokesperson says the $900 billion number was "made up"; Kerry's plan is to rescind Bush's tax cuts for the wealthy.) Then the ad paints Kerry as weak on terrorism.

The Bush strategy is to unleash the heaviest round of negative TV ads ever in order to discredit Kerry before he can solidify his lead. Sitting on an unprecedented mountain of money, the Bush team is blanketing 17 swing states between now and the GOP convention in late August.

Two weeks ago the first warm, biographical ads touting Bush's leadership were unveiled. But even those carried a surprisingly divisive edge, using images of 9/11 -- even a recovered body, which some victims' families and firefighters found tasteless and exploitative.

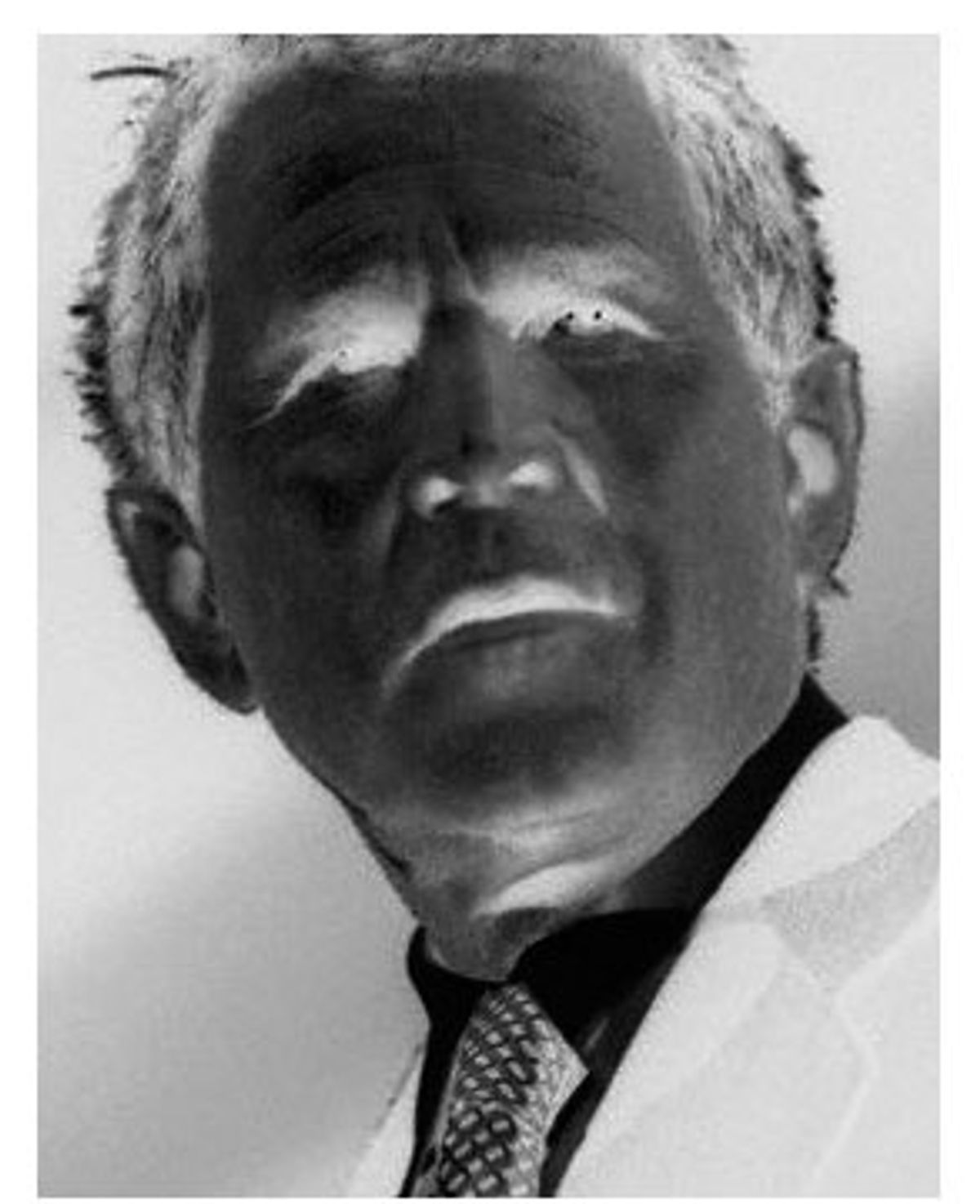

Now, as the Republicans enter attack mode, it's prime time for Alex Castellanos -- the charismatic, controversial and confrontational Republican media consultant. Castellanos is the party's ultimate hit man, hired by the Bush-Cheney campaign to put his stamp on the contest.

"Republicans have sent every signal that this is going to be a vicious campaign against John Kerry," says Democratic media consultant Rich Davis. "And Alex has a well-earned reputation for producing searing, negative ads."

"If I were John Kerry, I'd go get a catcher's cup and an asbestos suit, because I think they're going to come after him with everything but the kitchen sink," says Jim Krog, a Florida Democratic lobbyist. In 1994, Krog was chief of staff to Gov. Lawton Chiles and ran his reelection campaign. In that race he squared off against Castellanos. "He'll go after the jugular and rip it out," Krog says.

It was during that 1994 Florida campaign, working for Jeb Bush's first but failed bid for election, that Castellanos showed why he's considered one of the fathers of the modern attack ad.

Castellanos launched a classic October surprise. Less than two weeks before the election, with his candidate ahead in the polls, Castellanos produced a raw, emotionally charged spot featuring a Florida mother whose 10-year-old daughter had been murdered in 1980. On camera, she complained that Chiles had refused to sign the killer's death warrant, "because he's too liberal on crime." Addressing the people of Florida, the mother said, "I know Jeb Bush. He'll make criminals serve their sentences and enforce the death penalty. Lawton Chiles won't."

The accusation produced panic inside the Chiles campaign. "We had done all the research [on relevant death sentence cases] and we couldn't figure out how we missed this guy," says Krog. Aides quickly unearthed the answer: Florida courts were still hearing the killer's appeal, making it impossible for Chiles to act.

The Palm Beach Post condemned the attack ad as a "despicable lie that proves again why Jeb [Bush] is unfit to be governor." The Orlando Sun-Sentinel accused Bush of demagoguery, protesting the spot was "shamelessly false, irresponsible and tasteless," while the Miami Herald complained it had "sunk to new depths."

The ads backfired on Bush, allowing Chiles to win one of the closest gubernatorial races in Florida history. "You've got to be sure of your facts. Even with a lot of money, bad facts override it every time," says Krog.

And that wasn't even Castellanos' most infamous attack ad. In 1990, working for Republican Sen. Jesse Helms of North Carolina, he produced perhaps the most racially divisive TV ad in campaign history. Called "White Hands," it featured an angry white worker crumpling up a job rejection notice. He had lost out because "they had to give it to a minority."

More recently, in 2000, his firm National Media produced an ad mocking Al Gore's stance on prescription drugs, flashing the word "RATS" on the screen for a split second. Castellanos denied using subliminal advertising. Forced on the defensive, Bush had to yank the spot.

Over the years Castellanos has produced a trail of caustic ads either pulled off the air, like the Bush spot in Florida, or judged by his own Republican clients to be too misleading or biting for public consumption. Yet today, because of his expertise at the negative, he has been given a central role in the Bush campaign.

His Democratic Party counterparts grant Castellanos grudging respect and understand the reason the Bush campaign has tapped him. "He's one of the most talented people in either party, and I wish he was on our side," says former Clinton aide Paul Begala, now a Democratic consultant and CNN commentator. "It's like at the end of those old Batman episodes, when they catch the villain, and the police chief turns to Batman and Robin and says, 'If only he'd use that genius for good.' That's how I feel about Alex."

"He's smart as hell," adds Krog, who recently worked with the Republican strategist for a statewide voter initiative in Florida. "He cuts right to an issue and finds the throbbing vein as quickly as anyone I've ever seen."

But does Castellanos play the campaign game fairly? "Considering there are no rules, I suppose he does," says Harrison Hickman, who worked as Sen. John Edwards' pollster during his presidential run this year.

One characteristic that sets Castellanos apart from some of the nondescript Washington-based political consultants is that he's a red-meat ideologue, who offers no apologies for his assertive -- some would say crude -- attacks.

"Other consultants create hard-hitting ads but tend to be more apologetic about it," says Dan Schnur, a California Republican strategist who served as communications director for Sen. John McCain's presidential run in 2000. "Most consultants like what they do, but they also want to be invited into polite society. He creates sharp-edged stuff and will admit it. That's made him some enemies and earned him attention."

"He doesn't just make the ads and say, 'It's just a business and somebody has to do it,'" says Hickman. "He makes the ads and really believes them. He's not above politics, which is admirable in a way."

Castellanos is also not above spreading disinformation. In 2002, trying to turn the Enron scandal against the Democrats, Castellanos appeared on CNN and ABC, insisting that Enron CEO Ken Lay had slept in the Lincoln Bedroom at the invitation of President Clinton. The tale was reported far and wide, but it was completely false.

Spin doctor that he is, Castellanos insists that negative ads, even blatantly misleading ones, represent nothing less than freedom and democracy on display. "You know, ultimately all this messy stuff we have in politics, all this conflict, all this chaos -- by another name, it's freedom. And I think that a country that has fought so hard to earn its freedom and keep its freedom shouldn't give an ounce of it away," he once said on a 1998 documentary broadcast on PBS. "If you take all the negative aspects out of politics, if you take all the divisiveness out of politics, what you're left with is, is very bland, unimaginative oatmeal."

Nobody expects the unprecedented $100 million Republican ad blitz, especially with Castellanos as part of the creative mix, to be bland oatmeal.

"It's absolutely an unprecedented amount of money," notes Darrell West, a professor of political science at Brown University and an expert on campaign advertising. "There's never been an election where the incumbent spent $100 million before the convention."

The objective is clear: to turn the image of Kerry from war hero into flip-flopping professional politician. "I suspect most of what most voters will learn about John Kerry during the spring and summer is going to come from the Bush ad campaign," says Schnur.

Nonetheless, there's a risk to running so many ads early in the campaign, warns Kathleen Hall Jamieson, dean of the Annenberg School of Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, and author of "Dirty Politics: Deception, Distraction and Democracy." "If the ads are seen as legitimate and fair, it's OK. But for instance the recent Republican attacks on Kerry's past votes on defense spending have large gaps of evidence, yet are drawing large inferences. If we see similar TV attack ads like that, it will give the press, and the opponent, the chance to argue that Bush is playing loose with the facts. And also, what if the $100 million plays into the perception of, 'Whose money is Bush spending?'"

She sees another danger for Republicans hoping the $100 million-plus worth of well-placed advertising will win Bush reelection; in the wake of 9/11, the war in Iraq and concern about the economy, Americans are much more attentive to current events. That's bad news for campaign advertising. "Political ads are more powerful when people are paying no attention to news," says Jamieson. "This is not 1996."

But what if the ads don't work? What if Republicans spend $100 million between now and August and have little or nothing to show for it in the polls? If an unmatched flood of advertising does not produce a sizable gain for Bush, "I'd think some people would want their money back," says Hickman.

"If they spend $100 million and nobody listens and they don't pick up a big margin, and you're ABC or CNN, what story do you think you're running?" asks Krog. "So if you're going to spend $100 million, you better have knocked him out or the press will write the story about how you failed, and about how your opponent withstood an unprecedented TV attack."

"That's the risk," agrees Begala. "If this doesn't kill Kerry, it'll only make him stronger. He'll be able to say, 'I survived Vietnam and cancer and political death [early on in the Democratic campaign], and everything the Bush sleaze machine can throw at me.' That's a pretty compelling argument."

Still, Kerry supporters admit they wish he were the candidate sitting on a $100 million campaign war chest as the general election unfolds. It's more money than Alex Castellanos has ever had at his disposal.

The son of a Cuban refugee, Castellanos came to Florida in 1961 when he was 6 years old. His father arrived with two kids, one suitcase and $11. Castellanos has said his family's experience living under Fidel Castro's fledgling communist regime helped form his conservative, anti-government politics. "I believe this stuff," he once told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. "I have a general dislike for government that tells people what to do." (Castellanos did not return calls for this story.)

He became a National Merit scholar at the University of North Carolina and soon became an apprentice to Arthur Finkelstein, a prominent and reclusive New York media consultant known for relentlessly negative campaigns. In 1984, at the age of 30, Castellanos joined the team that produced the campaign spots for Sen. Jesse Helms, the ultraconservative North Carolina Republican. Experts say those ads -- 50 of them aired over 18 months, an unprecedented length of time for a media war -- marked a turning point in modern political attack ads, with their haunting, ominous music and relentless personal jabs. "The reel of ads they ran against Jim Hunt in 1984 was probably the best negative campaign I've ever seen in a political season," says Hickman, who has worked in North Carolina politics for Democrats for decades. "They took a candidate who had 70 percent favorable rating in Jim Hunt and completely reshaped his public image into a politician you couldn't trust."

Hickman recalls the best spot of the bunch, which featured a hand pulling the lever of a slot machine. As the wheels in the three windows spun around, viewers could hear Helms off-camera saying he intended to vote for Ronald Reagan's reelection, a popular gesture in North Carolina. Then, one by one, the slot wheels stopped spinning and showed in each of the windows a picture of Michael Dukakis, Gary Hart, and Jesse Jackson, as a voice-over intoned, "Where do you stand, Jim?"

In 1988, Castellanos was recruited for the Bush/Quayle '88 media team by senior media consultant Roger Ailes, now president of the Fox News Channel. Castellanos' most infamous spot commercial came two years later, the legendary "White Hands" ad he produced in the closing days of Helms' reelection campaign.

Running against a black opponent, former Charlotte mayor Harvey Gantt, Helms was trailing in the closing days of the election. The spot, which Castellanos produced on a Sunday and had on-air the next day, featured a white man sitting at a table, with the camera's focus on his hands, angrily crumpling up a job rejection notice, as a narrator says: "You needed that job and you were the best qualified. But they had to give it to a minority because of a racial quota." Then the on-screen image of the rejection letter faded to a picture of Gantt, as the man's white hands, for a split second, appear to be crushing Gantt's head.

Helms won the election, and the "hands" ad was considered a key turning point. "A lot of people after the fact would say, 'That's horrible.' But it worked," says Krog.

Jamieson says that the subliminal, sleight of hand approach should be off-limits: "There should not be content in an ad that has meaning but that viewers are not completely aware of."

Bush's new Kerry attack ad, which some Arab-American groups say should be taken off the air, also flashes a controversial image loaded with negative meaning. In an ominous portion of the 30-second spot that warns voters about Kerry's opposition to the USA PATRIOT Act, the words "John Kerry's Plan" flash on-screen, while on the bottom a red box warns, "Weaken Fight Against Terrorists." There are also boxed images of three people -- a traveler, a man in a gas mask, and a sinister-looking olive-skinned man with bushy eyebrows peering into the camera. Bush campaign officials say the actor is supposed to represent a generic man, not a Mideasterner. But Arab-American officials insist the image is obviously playing on simmering, post-Sept. 11 mistrust. The ad "can only create fear and suspicion and should be changed immediately," says James Zogby, president of the Arab-American Institute in Washington.

Some of Castellanos' hard-hitting ads, however, have backfired and caused headaches for his clients. The same year as the Jeb Bush fiasco, Castellanos worked for Guy Milner, trying to unseat Georgia's sitting Democratic governor, Zell Miller. The key theme of the campaign was crime (Milner called for abolishing parole) and Castellanos produced an ad featuring Milner's daughter as she told a harrowing tale of the time her house was broken into and awakening to find a strange man at the foot of her bed. "It was heart-wrenching stuff," Miller's former advisor told Salon in 2000. "The only problem was that the incident happened in Nashville, Tenn., 15 years earlier, when Republican Lamar Alexander was governor. It was an incredibly negative, misleading ad."

Two years later Castellanos was fired from Helms' 1996 reelection campaign after he aired an unusually negative ad early on during the Democratic primary, tying two candidates to racial quotas and health benefits for homosexuals.

Late in the 1996 presidential race, Castellanos was hired by Sen. Bob Dole's floundering campaign. But the consultant, who wanted to air spots labeling Clinton a liar, clashed with the campaign officials and the candidate himself, who felt Castellanos' tactics were too caustic and disrespectful. One rejected ad featured images of Clinton set to the song, "You Cheated, You Lied."

Immediately following the election, Castellanos, who aired his complaints about Dole as a bad campaigner when interviewed on CNN, showcased his rejected commercials in public presentations and for the media. The move was considered to be in bad taste among many professionals, who insist the client calls the shots, not the consultant. Says one political consultant: "Our firm would never parade ads around in public that our client rejected."

In 1998, Castellanos produced ads for Bob Taft's race for governor in Ohio. One spot became the first gubernatorial commercial ever cited by the Ohio Elections Commission for lying. In fact, the commission found that the television ad lied twice about Taft's Democratic opponent. (The ruling meant Taft's campaign had broken the very election laws that he, as secretary of state, had pledged to enforce.) Yet another Taft campaign ad became the subject of an unprecedented temporary restraining order, issued so an Ohio judge could determine whether the commercial was a fraudulent misrepresentation. The judge eventually relented.

Then the "rats" ad appeared that nearly cost Bush the 2000 election. It aired at a moment when the candidate was falling behind as a result of Gore's post-convention bounce. Castellanos' ad slammed Gore's plan for prescription drugs for seniors. The word "bureaucrats" appeared onscreen in large white letters. Then as the frame changed, "RATS" was broken off and blown up on the screen for one-30th of a second. When the New York Times put the "rats" story on Page 1 in late September, the Bush campaign was thrown onto the defensive as Bush wrestled over the word subliminal, pronouncing it "subliminable." Castellanos unconvincingly denied he had inserted the word intentionally.

Even before the "rats" debacle, Bush spiked an earlier Castellanos-produced spot that included a video clip of Gore saying he'd never heard Clinton tell a lie. But the ad failed to disclose that the Gore clip was actually lifted from a 1994 interview, years before the Monica Lewinsky episode. Castellanos also goofed when he got the Republican National Committee to release a spot he made in September 2000 touting a new prescription drug plan the candidate was about to present. Bush, in fact, had no such plan. It was a Castellanos invention.

Time and again, Castellanos cannot seem to resist charging to the edge of acceptable behavior and sometimes over it. "If you don't understand where the line is, it will backfire," says Hickman. "Does [Castellanos] play near the line when he doesn't have to? Yeah."

Now, the Bush campaign will invest more money than ever before in a media onslaught. "We'll test the hypothesis that money matters," says Jamieson.

And that vast amount of money is about to be spun into negative TV ads by the Republicans' most notorious practitioner of the trade. Alex Castellanos is ready for his screen test.

Editor's note: This story has been corrected since its original publication.

Shares