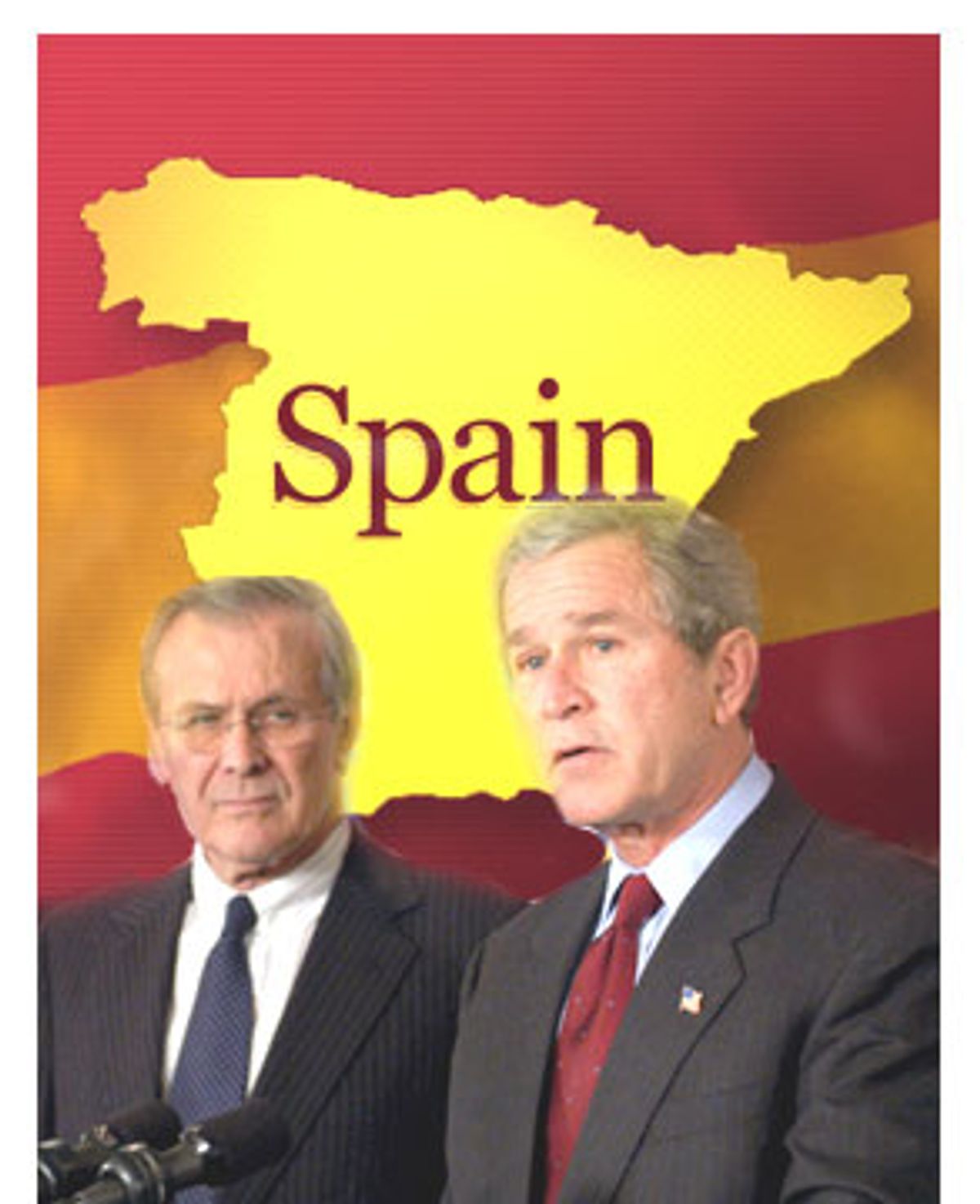

When the terrorist bombs exploded at the Atocha train station in Madrid, Spain, on March 11, a date that resonated like a depth charge as a European 9/11, politics on both sides of the Atlantic were thrown into turmoil. The ruling conservative Popular Party in Spain and the Bush administration instantly staked the Spanish election on the presumed identity of the terrorists. The Spanish government had supported Bush's war in Iraq in his "coalition of the willing" against the overwhelming opposition of Spanish public opinion. March 11, therefore, must not be Sept. 11, at least not exactly. The culprits must be ETA, the Basque separatists, not al-Qaida. Prime Minister José María Aznar repeatedly called Spanish newspapers to insist that ETA was responsible. Within hours of the attack, President Bush and Secretary of State Powell helpfully pointed their fingers at ETA. There was no mention of al-Qaida at the White House.

A day before the election, however, alleged terrorists linked to al-Qaida were arrested. The credibility of the government was in tatters and it suffered a shattering defeat. March 11's explosions had revealed the barely buried history of Franco's relentless political exploitation of terror to sustain his power. José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, the new Socialist prime minister, immediately pledged his commitment to the war on terror, while calling the war in Iraq a "disaster," and, for good measure, announcing, "I want Kerry to win." John Kerry, for his part, called for Zapatero to reconsider his decision to withdraw Spanish troops from Iraq. Each of their statements reflected the complex reconfiguring of politics after March 11. The crisis in the Western alliance, prompted in reaction to Bush, is a new peril to be navigated by Kerry.

On the eve of the Spanish election, Bush's first wave of campaign spots on television had failed. He launched his effort by wrapping himself in 9/11, featuring a flag-draped coffin at ground zero. By more than a 2-1 majority voters felt the ad was inappropriate and Bush hastily withdrew it. He replaced it with a more menacing commercial. The ad claimed (falsely) that Kerry had a plan to raise taxes by $900 billion. Pictures of working women were flashed on the screen. Hidden message: Kerry would harm women. Then came a triptych of rapid images: a U.S. soldier (was he patrolling in Iraq?), a young man looking over his shoulder running down a city street at night (was he a mugger or escaping an attack?) and a close-up of the darting eyes of a swarthy man (was he a terrorist?). The voice-over: Kerry would "weaken America." The images -- abstract, racial and subliminal -- were intended to play upon irrational fear. A Bush spokesman explained that the generic olive-skinned figure was a hired actor and that he wasn't an Arab. Through this literal-mindedness the Bush campaign tried to deflect criticism as it sought to implant apprehension about Kerry.

Though Kerry is the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee and has served in the Senate for 19 years, he is not well known, but a vague figure to many voters, especially the undecided who do not regularly pay much attention to politics. Yet he is even with or ahead of Bush in the polls. For Bush, the next 60 days may be decisive in shaping Kerry's identity. The elder Bush, lagging in 1988, waited until after the Republican convention in late summer to paint his opponent as a soft liberal, weak on defense, somehow un-American. This President Bush cannot wait as his father did.

On every issue of domestic concern, Kerry defeats Bush. Only on foreign policy does Bush hold sway, so he must heighten and reinforce that difference. Kerry must be weak, Bush must be strong. Thus a new Bush ad: Jets take off from an aircraft carrier, a female soldier hugs her family, and the voice-over, "Kerry ... wrong on defense." Once again, through the images, Kerry is depicted subliminally as hurting women. (The ad claimed that Kerry voted against an $87 billion post-Iraq war appropriation, failing to note, of course, that he had proposed linking it to rescinding Bush's tax cut for the wealthy.)

After Spain, the White House that had originally insisted it was ETA and not al-Qaida that was responsible for the Atocha station attack pivoted its argument. The Spanish vote was not a triumph of democracy, a revulsion against the political manipulation of terror. Instead it is being construed as a victory for al-Qaida, a blow in the "ideological war on terrorism," as the neoconservative editorial writer Anne Applebaum of the Washington Post put it.

The neoconservative chorus is as one voice. "Are Europeans prepared to grant all of al-Qaida's conditions in exchange for a promise of security? Thoughts of Munich and 1938 come to mind," wrote Robert Kagan in the Washington Post, in an anxious updating of his famous planetary projections of Europe as Venus and the U.S. as Mars. Astrology, not history, is the long suit here. What would the Spanish know of fascism? Charles Krauthammer, another Post columnist, held forth on Fox News, "We are hearing the voice of European decadence."

The Bush Doctrine as a doctrine has evaporated. Whether it was ever a doctrine rather than a rationale for an already decided upon invasion of Iraq is questionable. Certainly, the war in Afghanistan was a response to an attack on the United States, not a preemptive strike. Rejected now by a member state of NATO through its democratic process, the doctrine per se has no practical future as an instrument of foreign policy, if it ever did.

But the consequences of Bush remain center stage. As the arrogance of power increasingly leads to the dissolution of power, the "ideological war" becomes more furious. For the neoconservatives, the political meaning of 3/11 must be forced into the Procrustean bed of Bush's 9/11. Bush's campaign, after all, turns on the preemptive strike.

Shares