Mike Ditka is staring me down, trying to intimidate me with his icy, unblinking blue eyes. The fleshy finger of his left hand is extended and aimed, pistol-like, directly at my face. The guy looks ruthless. Cruel. Downright menacing. Which is a little bizarre, actually, considering that Mike Ditka -- one of the NFL's most notorious badasses, a Pro Bowl tight end, a Super Bowl-winning head coach, a man whose very stare lets you know that he is The Man -- is putting on this red-blooded act because he's concerned about my penis.

All this, and I'm just sitting on the couch.

Here I am, watching TV, my programming interrupted by one of those ubiquitous commercials for Levitra, the erectile dysfunction (ED) drug for which Mike Ditka has recently become spokesman, lending his famously "smashmouth" persona to promote a product about as manly as Monistat 7. And there he is, Mr. Man, taunting me to "take the Levitra challenge," chiding, "How tough can it be?" In other words: Mike Ditka is calling me a pussy because his penis doesn't work and, well, he wants to know how mine's doing.

And I'm so used to this that it takes a moment to register as strange.

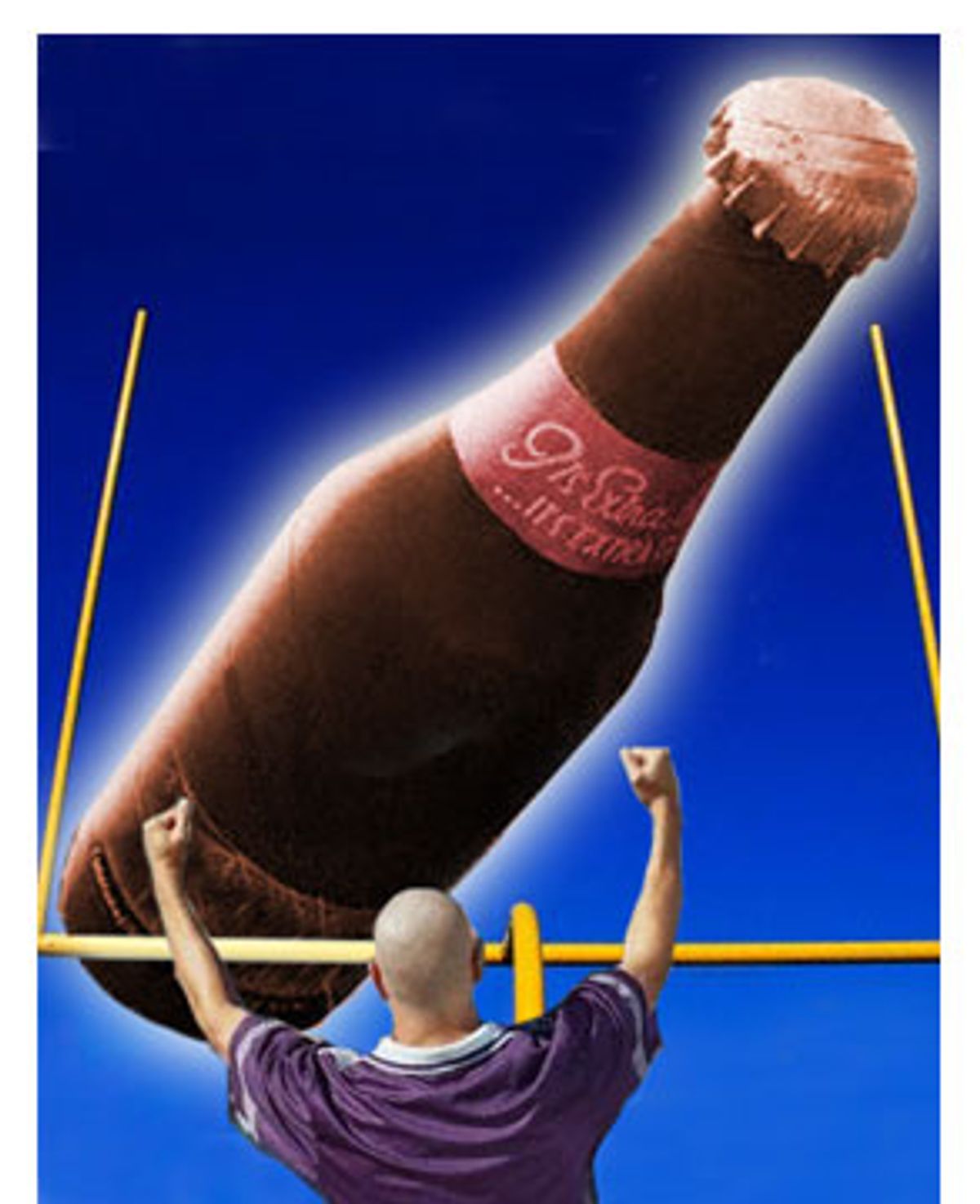

Viagra may have just celebrated its sixth birthday, but it wasn't until recently, starting this past football season, when Levitra, and then Cialis, made their national debuts that malfunctioning penises became truly embedded in the American ethos. If you've sat on your couch watching TV for longer than 10 minutes lately you know what I'm talking about: pitches for puttering penis cures assault you with the same commando-style aggressiveness as those for bullet-proof SUVs and babe-magnet beers. For instance: In Levitra's Super Bowl ad, Ditka scoffs at baseball players, calling them chumps in comparison to football players who have the "toughness" required to "stay in the game." Clearly this is a not-so-sly jab at Rafael Palmeiro, the Texas Rangers slugger and Viagra spokesman, but it's certainly a strange dig when you think about it: Ditka is saying (follow me here) that he's manly enough to be sensitive enough to admit that his penis doesn't work well enough.

It's kind of funny, yes.

It's also audaciously brilliant marketing. The suits at GlaxoSmithKline, the pharmaceutical giant responsible for Levitra, are in a sense trying (with some success) to make impotency synonymous with virility: the perfect gimmick for a country whose sexual identity is so schizophrenic that we demand T&A from all TV programming yet get in a tizzy over a microsecond-long peek at Janet Jackson's actual goods. The initial ads for Levitra were some of the most peculiar in memory: A guy who has the Marlboro Man's rugged handsomeness and indeterminate age (maybe he's 35, maybe 65) finds an old football in the shed, dusts it off, and tries to toss it through a tire swing. But ... he hits the rim! Poor guy. Cue Levitra's logo (a virile orange flame); cut quickly back to the man: Lo and behold, the ball is going through the hole like there's no tomorrow! His girlfriend/wife comes out to join in the fun! What a babe! Can't be older than 35! They put the ball through the hole together! Over and over and over ...

As laughably literal as it was (a friend of mine joked that Levitra was for men whose penises always just miss locating their partner's vaginas), the ad was effective in A) making its point without having to actually make its point (and therefore being able to avoid mentioning the disquieting possible side effects like dizziness, nausea and those rare four-hour-long erections); B) linking impotency with über-masculinity in the same manner the Marlboro Man did with smoking many moons ago; and C) making Levitra seem cool in a grisly, macho sort of way. "Our goal with that ad was to mobilize men to take action," says Michael Fleming, director of product placement at GlaxoSmithKline, who claims that the spot caused a 36 percent spike in men asking their doctors about ED. Whether that's true or not, one thing is certain: The ad was so effective that it seemed like the folks behind Cialis, the ED drug that lasts a whopping 36 hours, had no idea how to top it when they entered the fray in Levitra's wake.

I mean, just look at the Cialis ad (flashing right now on my TV screen, only two minutes after Levitra's!): A husband and wife -- notice the ring -- sit peacefully in separate old-fashioned bathtubs, perched atop a pristine country hill, touching hands, blissfully taking in the view. The viewer is asked, by an omniscient voice: "Are you ready?" Basically, Eli Lilly is attempting to market hot sex the same way Hallmark markets eternal love: gauzily, delicately, completely nonsensically. The two tubs are like a modernized version of the separate beds in which the '50s sitcom couple sleeps. And what's with the tubs, anyway?

When I pose this question to Carole Coupland, spokesperson for Eli Lilly, she first makes a point of saying that, no, the ads were in "no way" affected by Levitra's machismo marketing strategy and that, no, Cialis has no plans for any "train-through-tunnel type stuff in the future." Then she explains the logic of the commercial: "It wasn't as if we hired any tub consultants, or anything like that. The tub was chosen because it was an arresting image, the kind of thing you see and think: Wow, I'd love to be there!" (Oh ... OK. My only guess had been that Cialis had given this couple so much repeated pleasure -- 36 hours! -- without diminishing performance that they had to stick the old guy in a tub of ice to cool off.)

And yet: The fey little Cialis ad becomes almost as super-masculine as Levitra's, thanks to the fact that during nearly every commercial break on nearly every major channel you can watch the two duking it out for some sort of ED Awareness Award (just imagine that trophy).

TV, especially sports TV, has up to now been a kind of last bastion of clichéd portrayals of masculinity. You saw that men liked beer. That men got lots of bleached, tweezed, halter-topped babes (often because men drink so much beer). And that men drove really big trucks (because, in part, they could hold lots of bleached, tweezed, halter-topped babes). It was an inane vortex, no doubt, but it was also a kind of absurd sanctuary where men could slump into the sofa cushions, do absolutely nothing, and still feel like masters of the universe.

Well, not anymore. When Viagra came on the scene ED still seemed like an embarrassing ailment, largely because Pfizer hired an old, cold guy like Bob Dole to spread the love. Now the onslaught of ED ads -- and their fierce competition to one-up each other -- has (accidentally) exposed a glaring truth that many of us liked to ignore while zoning out in our living rooms: Men drink too much beer. Sexual malfunction ensues. Hence the purchasing of automobiles to compensate for chronically flaccid penises. Which, well ... just doesn't quite do the trick.

The executives at Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, and Eli Lilly have (unwittingly) pulled off a vaguely feminist agenda: a national unearthing of male vulnerability, and not just among super-sensitive urban types; they've exposed the (literal) soft spots of those stoic dudes in the middle of the country as well. The toughest, most challenging men to reach when it comes to such persnickety issues are now ready to ask for help en masse. They're admitting that, truth be told, they're not the bedroom stallions they've been purporting to be.

Which is kind of endearing, actually.

It's also important. The very fact that these ads are so omnipresent highlights a barely hidden subtext of their overall goal: These drugs are being marketed not only to those men who need them, but to those who merely want a little extra help in the erectile department, too. (I'm in my 20s, still shaking off my adolescent husk, and I'll admit that I'm a bit curious about Levitra, if only because I developed a slight crush on the impotent guy's girlfriend in the commercial; I'd be embarrassed to tell you this if I didn't think that millions of others feel the same way -- if I didn't open up GQ magazine, which is these days aggressively targeting men my age, and see a "test drive" of both Cialis and Levitra.)

Of course, the companies won't confess that they're selling lifestyle drugs, but the whole trick is that they won't ever need to. Zoloft, after all, entered the market as a drug for the clinically depressed, the sort of pill swallowed by your fragile friend who only listened to the Smiths and talked constantly about suicide -- the kind of person (kidding aside) who really needed help. But then last year the drug was quietly approved by the FDA for treating "social anxiety disorder," something that in earlier eras was diagnosed as "shyness" or "sadness," and cured with a prescription of "you'll get over it." The term "erectile dysfunction," meanwhile, is already malleable enough to apply to any penis that acts the slightest bit finicky (e.g. all penises). Zoloft is having enormous success for a simple reason: We humans are a pretty sad lot. Levitra, Cialis, and Viagra are now exposing something else: We humans have pretty tepid sex lives, too.

But is this really just because many of us American men can't get it up anymore? Can it be that simple?

In some cases, yes, it is, and in those instances these drugs are truly wonderful. (I'm sure that if I'm not blessed with, say, Saul Bellow's stamina in my twilight years, I'll probably give one of these pills a go.) When Carole Coupland at Eli Lilly tells me that they interviewed "thousands of men and their partners," with the goal of "helping them become spontaneous again," I must say that I'm genuinely touched. At the same time, I can't help but think these cases are the minority. Though it's unlikely that a study will ever be conducted to support this, my theory is that the majority of men asking their doctors if a free trial is right for them are doing so, in large part, because of a more complicated reason: They're stilted; they have no idea how to communicate what they really want in bed.

Men are a notoriously dense species, but one whose oafish exterior is offset by a jittery undercurrent of wants and needs just as fragile as you find in any female. So maybe what these ads and drugs are surreptitiously pointing out is just how few men really have a grasp on how to express this side of themselves and, with it, their true bedroom wishes.

I'm really not making such a leap here: We are a country where the unabashed force driving all mass media is the concept of sex, whereas anything hinting at actual sex is demonized. Hence the NC-17 rating given to Bernardo Bertolucci's "The Dreamers" because the film shows a close-up of a (flaccid) penis, as if staring straight at that diabolical part of the body would cause untold damage to the same masses being inundated with ads promising turbocharged erections.

Simply stated: When it comes to sex, we are a masturbatory nation, far more comfortable being aroused by thinking about doing it than actually doing it.

Sex, as anyone who has done it knows, is a funny and awkward endeavor, and that's part of what makes it such glorious fun: you feel vulnerable, sliced down the middle, all your pros and cons out on the table, saying: Take it or leave it (but please, please take it). The same way that all of us find ourselves depressed, the fact is that every man, to one degree or another, finds himself at odds with his penis over the course of a sexual life. ("At times the urge intrudes uninvited," St. Augustine wrote during the third century A.D. "At other times, it deserts the panting lover, and, although desire blazes in the mind, the body is frigid.") Maybe the cause is too much booze. Maybe it's fear of wanting something sort of kinky from someone who seems sort of square. Maybe it's being so emotionally overwhelmed that your physicality goes momentarily haywire. What the current onslaught of ED drugs overlooks is that the cause of the "problem" may be more important than the supposed solution, and that embracing, rather than shunning, our vulnerabilities may be as effective as popping pills.

But let's be real: That's an awfully sissy way to look at things, especially when Mike Ditka appears on my TV, yet again, telling me to stop being such a pansy, and to go out there and get a goddamn erection.

Shares