With more and more pictures clamoring for our moviegoing dollars each year, we need to ask ourselves, What's more valuable, an interesting failure or a merely competent success?

"Intermission" is the full-length feature debut of Irish theater director John Crowley, and it has its share of aggravating flaws. It's also one of the most ambitious film debuts in years: "Intermission" is an ensemble crime-caper drama that hits plenty of romantic-comedy notes along the way. This is an entertainment with wily dramatic undercurrents and a wry, rough sense of humor, and in an age where marketing matters even more than the product that's being sold, how does a distributor even begin to market that?

"Intermission" also features more than a dozen characters, and their stories dovetail deftly but also in ways that surprise us without stretching the boundaries of believability (at least not too much). As I watched "Intermission," I kept wondering, who even bothers to make a movie like this today -- a strange, sprawling little picture about everyday lives that neither inflates the profundity of its characters nor condescends to them?

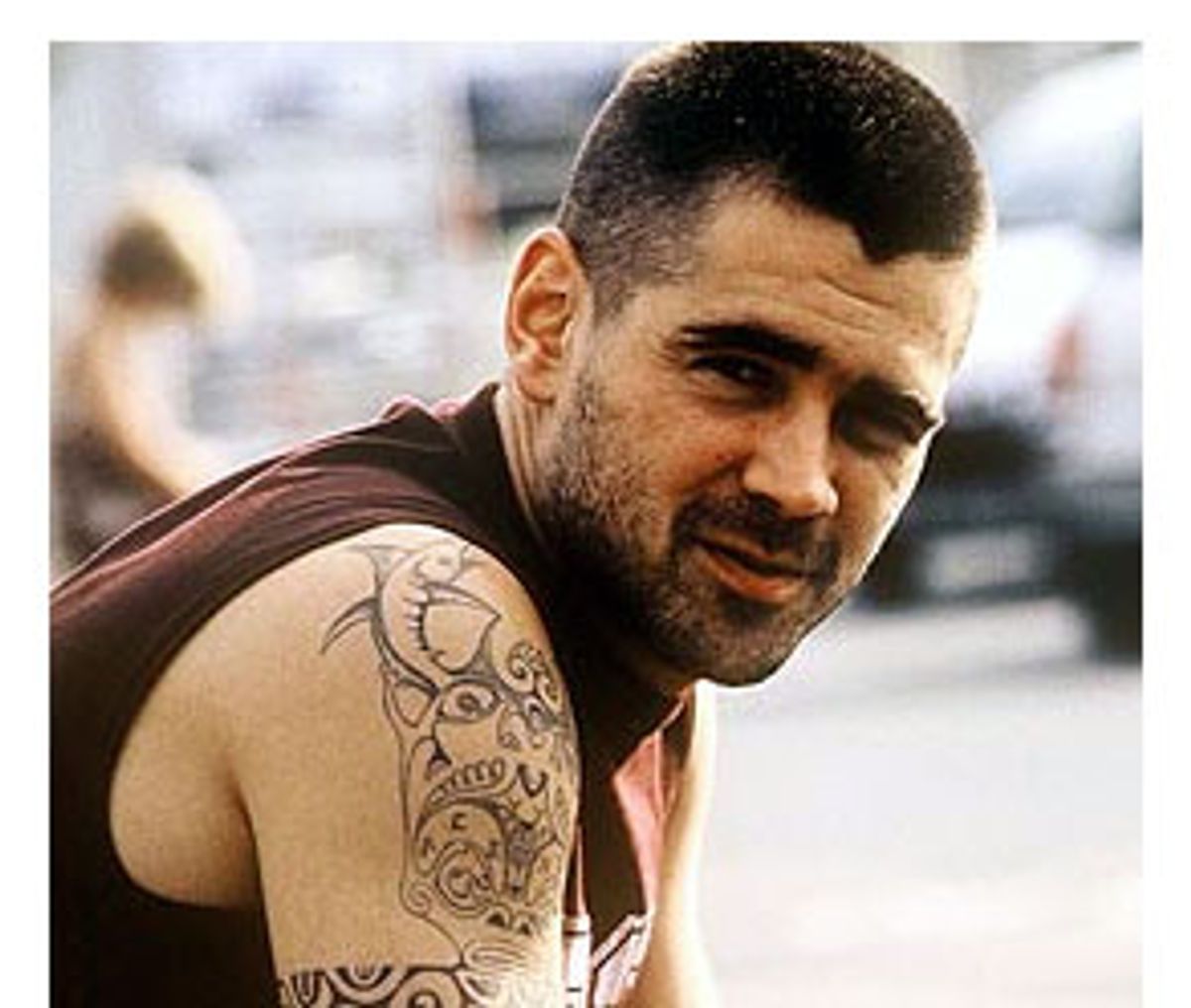

In the opening scene of "Intermission," Colin Farrell, as a seductive but mean-tempered petty crook, chats up a young woman behind a Dublin coffee-shop counter. I won't give you the details of what happens next, but I will say it knocked me on my heels, partly because of how much it told me, in a very compact measure of time, about Farrell's character. It also suggested that neither Crowley nor the movie's screenwriter, Mark O'Rowe, had much interest in fooling around.

The beginning of "Intermission" features an exhilarating and somewhat brutal chase sequence, scored to U2's gloriously disreputable-sounding "Out of Control." When was the last time you heard a U2 song used in a movie as anything other than a predictably benign advertisement for loving thy neighbor or taking good care of the planet? From the start, "Intermission" fearlessly bares its teeth.

Then again, sometimes it's really just flashing them in a Cheshire-cat smile. "Intermission" is an exceedingly mischievous picture, and not one that's always easy to get a handle on. We're invited to laugh at elderly quadriplegics, and also to find a measure of sympathy for thuggish crooks who really just want to settle down and spend some quality time in the kitchen. The mood of "Intermission" turns on a dime, and it turns often -- there are times when its ever-shifting tones veer out of Crowley's control. Somehow, though, he's always able to corral it just in time, and mostly, he does manage to keep a grip on the movie's scrambling, skittering plot.

Farrell has a grand (and extremely illegal) moneymaking scheme in mind, but he needs partners to pull it off. He recruits a surly pal (Brian F. O'Byrne), who has recently lost his job as a bus driver (the sort who always used to refuse to cut his passengers, even the old-age pensioners, a break). Later, one of O'Byrne's friends, played by Cillian Murphy (whose chiselled cheekbones emerged in last year's "28 Days Later"), is drawn into the plan.

Murphy's character is sullen and opaque, and we know why: He has just broken up with his girlfriend, Kelly Macdonald, solely to test her affection for him. She wastes no time launching into an affair with a dull but upstanding bank manager (Michael McElhatton), who has flat-out deserted his wife of 16 years, played by Deirdre O'Kane, who, now on her own, is about to get in touch with her inner dominatrix.

The pinwheel of "Intermission" starts spinning madly, pulling more and more characters into its whirl: There's Colm Meaney as a tough-guy detective, David Wilmot as a lonely, sweet-natured singleton, Shirley Henderson (who played the scrappy wife in "24-Hour Party People") as a troubled young woman with a mustache, and a mysterious little kid who causes a whole lot of trouble just by throwing a rock. All of that may sound tremendously confusing, but the amazing thing about "Intermission" is that it isn't: O'Rowe's script keeps you wondering what's going to happen next, and to whom, with a notable absence of gimmickry.

"Intermission" is ambitious not just because the story has so many threads, but because Crowley relies so heavily on the skill of his actors. That may seem like a strange thing to say, given how essential actors are to movie storytelling. But we've all seen movies in which a director's overarching vision actually prevents actors from doing their job. For all the complexity of "Intermission," it rarely feels cluttered, simply because Crowley lets his actors' faces, voices and movements tell most of the story. (The editing, by Lucia Zucchetti, serves them well too -- it's lively when it needs to be, but it always stops short of being kinetic.)

In the hands of the right director -- Robert Altman is probably the master -- ensemble movies can be stunning showcases for actors. But more often than not, they're disastrous: Think of the Richard Curtis train wreck "Love Actually." In "Intermission," each character is distinct and whole: Even the ones who get very little screen time emerge as fully rounded beings.

Farrell doesn't have a whole lot to do here, but he's riveting whenever he's on-screen. His hair has been shaved down to a belligerent stubble, and there's a hardness in his eyes that's sometimes just on the verge of softening. It's a performance that's wound so comically tight, it almost makes you nervous to watch it, and yet there's no turning away.

Macdonald (who made her movie debut in "Trainspotting" as a tough-cookie schoolgirl, and also had a memorable turn in Raymond De Felitta's tenderhearted, little-seen "Two Family House") is lovely here. Her character may be confused by her boyfriend's behavior, as any young woman would be, but she's too sensible to be undone by it. Macdonald is coltishly graceful in the way she carries herself, and there's both a flirtatious naughtiness and a highly practical self-sufficiency about her. She shows every sign of growing into the kind of serious actress who's always a pleasure to watch (as opposed to the kind who makes you sweat along with her).

According to the press notes for "Intermission," the actors had only a week and a half of rehearsal time before filming began. Given that bit of information, the ease with which they connect is remarkable. But their interactions are also, unfortunately, undermined by one of the movie's biggest flaws: "Intermission" features far too many tight close-ups. Too often the images feel unwieldy and oversized, as if they were TV-scaled pictures blown up to fill a movie screen. I don't know if that's a preference on the part of the cinematographer, Ryszard Lenczewski, or if it's because most of Crowley's experience has come from the theater. It's often difficult for theater directors to learn to think cinematically, but beyond that, I wonder if Crowley just found himself so entranced by his actors' faces that he just couldn't get enough of them -- a case of using the wrong technique for all the right reasons.

Still, the actors survive it. The mustachioed Henderson and the lonely misfit Wilmot have an almost-love scene together that's both casual and gleaming. And in one of the movie's subtlest, sweetest moments, a long-widowed mother, played by Ger Ryan, explains to one of her grown daughters why she never remarried. Her reasons are unsentimental, unvarnished and perhaps a little sad, given how we all want to believe that middle age is a stage that never really ends. Ryan plays the scene with the perfect balance of restraint and emotional openness. It's the kind of small-scale but sharply felt writing and acting we always wish for in the movies, such that it almost seems miraculous when we get it.

The plot twists of "Intermission" are gangly at times, and two-thirds of the way through, I did start wondering, a bit restlessly, how it was all going to come together. But after it was all over, I realized that I'd just seen something -- I wasn't quite sure what it was, but it was surely something. The occasional messiness and missteps of "Intermission" may have clamored noisily for my attention. But they hadn't come close to drowning out its heartbeat.

Shares