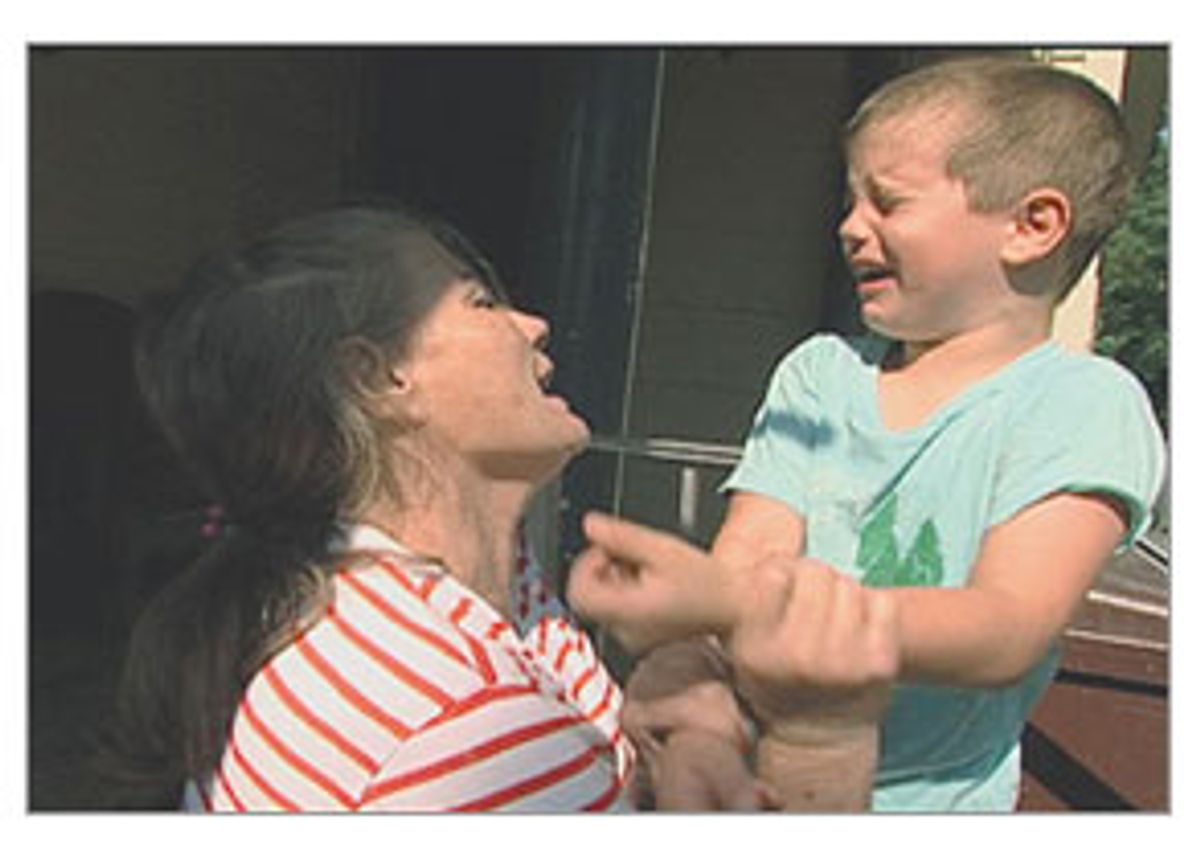

Wednesday night HBO airs "A Boy's Life," the newest film by documentary maker Rory Kennedy. "A Boy's Life" unfolds over two years in rural Mississippi, tracing the progress of Robert Oliver in his seventh and eighth years. Grandmother Anna is raising Robert and his younger brother, Benji, since their mother, who got pregnant as a teenager as the result of a rape, feels she cannot provide for her sons. Anna introduces us to Robert at the start of the film and paints the picture of a scary kid -- the kind that kills his house pets, has tried to kill himself, fiddles terrifyingly with the gas knob on the stove, and has wild tantrums. He's medicated to the gills.

But as the film progresses, we see Robert flourish in a new school, and a much creepier narrative takes shape, one that throws the familial premise of the film into question. It's not easy to watch: In one blood-curdling scene Anna lets hyper Robert play with a gun while the rest of the family hangs out in the front yard. He holds the heavy metal weapon above his head unsteadily, waving it precariously while his grandmother taunts him for being too weak to pull the trigger.

It's the pull-no-punches fare we've come to expect from Kennedy and her production partner Liz Garbus, who together run Moxie Firecracker films and have produced other chronicles of impoverished America, including "American Hollow" (also directed by Kennedy) and "Girlhood" (directed by Garbus).

Kennedy is the youngest daughter of the late Robert Kennedy; she was born six months after his assassination in 1968. While she's not chronicling some of the gruffer realities of American life, Kennedy, who is six months pregnant, lives in Brooklyn with her screenwriter husband, Mark Bailey (the story editor on "A Boy's Life"), and their 17-month-old daughter, Georgia. She spoke to Salon on Tuesday by telephone.

How did you find Robert? And when?

I had intended to do a film about welfare reform, looking at how the changes in welfare were going to affect children. There were about 100,000 children who were going to be turned off the rolls. A good portion of those were children with mental illness. I was looking to profile a family that fit that description. I had been told about Robert by his therapist, who said, 'I'm working with a child who has tried to commit suicide and has killed four dogs and three cats and is on a number of medications.' I wanted to meet him. Then we went down there and met Robert and it was clear that this was a child in need of assistance. But it was also fairly evident -- we only spent three or four days there, but even in that time frame -- that there was a lot more going on with the family. I came back from that trip and showed some of the footage to HBO and talked with them about doing a different kind of film that would just focus on this one family.

Are you still in touch with them?

Yeah, I have been in touch with them. They continue to do well. Robert and Benji are still living with their mother. They changed schools again, but they are both on the honor roll and have made a lot of friends. Robanna [their mother] has recently published a book of poetry and she is actually heading to a poetry conference in Denver in couple months. And Anna, believe it or not, is doing great, according to Robanna. According to Robanna, she is much more supportive of the children and of Robanna herself. She ended up going into a mental hospital and now goes to community therapy three or four days a week and is really doing great.

You've directed two films about the American South. What is your interest in the area?

It's a little bit of a coincidence. With "American Hollow" I was interested in the region itself, in Appalachia, which had something to do with my father. He had spent time down there and had been really impacted by his experience, so I'd always been curious about it. The truth is both of these films, "American Hollow" and "Boy's Life," have come out of this other film about welfare reform which I have yet to do ... so I should just keep making this welfare reform film and then I'll get 15 other films under my belt.

Would you say your main interest as a filmmaker is in issues of class?

Class is an enormously important issue to me. I think it's one of the most important issues not only in this country, but in the world. And so it is definitely something that I look toward and think about often -- the discrepancies between rich and poor in this country, and that gap growing bigger and bigger. It certainly informs a lot of other issues that are important to me, whether that's race or mental health issues.

Has your professional ambition been to be a filmmaker or a social advocate? Did you ever consider making blockbusters or romantic comedies?

When I graduated from college I had been doing research on an issue for a final paper about women and substance abuse. I met a number of women in that situation and felt when I talked to them directly that they were so convincing that if they could tell their stories to policymakers it could make a difference. So I made a film called "Women of Substance," and I really loved the experience. I had never taken a film class and hadn't intended on continuing to make documentaries, but in the process of making it I really fell in love with the medium. I came to making documentaries more with an interest in social advocacy than a love and passion for film. That's shifted somewhat, but I continue to choose topics that have some sort of social implications and create an awareness about something people haven't thought so much about.

Are you tempted to get involved in some of the unfortunate family situations you document? Do you get upset at what you're filming while you're filming it?

Of course. I don't go into these projects with a sense of trying to remain outside of the experience of it. It's important to remain open to the people you're filming and what they're experiencing. I don't try to close myself off from that, which means that I'm emotionally pulled into the situations.

Being a documentary filmmaker is different from being a journalist, although I try to maintain a journalistic integrity to the films. But [the films] are usually from the perspective of these families or these communities. They don't pretend to be otherwise. I followed this family for over two years. Of course you get attached.

You and your production partner Liz Garbus are Brown graduates and you come from a publicly powerful and privileged family. Are you conscious of the sharp class differences between you and some of your subjects?

Absolutely. I'm certainly aware of those differences. One thing that is continually remarkable to me is bridging those differences and seeing so many similarities with people from different backgrounds and reaching across those differences and trying to touch the humanity in all of us.

What is the most gratifying part of what you do for a living?

A lot of people think of work as part of their life and life as the other part of their life and I definitely feel that they are one and the same. I learn so much from people I meet and places that I go. I feel lucky to be in new and unique and challenging situations and not have any kind of monotony or sameness in my job life. And with many of these films I use them to have an impact. I did a short film about AIDS in 1999, when the global AIDS crisis hadn't been on people's radar screens so much. I was able to show it on Capitol Hill and Senator Leahy came up to me after the screening and said "You know I had the opportunity to see your film about a month ago and I want you to know I put an additional $25 million in the budget as a result of watching that film." Obviously I don't experience that kind of reward every day, but that is testimony to the impact of this medium.

You grew up in a family whose every move was documented on camera. Is your work a way of turning that camera on other families in the interest of doing good?

I personally didn't feel that my personal life was documented to an extraordinary degree. There were moments at certain types of events where there would be photographers or cameras. But I didn't feel like there was a press corps following me in my childhood. So I didn't have that experience per se. But the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial had a journalism award, and the journalism award went to journalists who pursued stories that were of interest, or would have been of interest, to my father, so that was certainly something that influenced me. There have also obviously been many documentaries about my father, whom I didn't know. [They] helped bring his legacy to life and I certainly experienced some connection with him through that medium, which was mostly a very rewarding and positive experience. So that probably had something to do with it, but again I really didn't set out to make documentaries and to pursue that my whole life.

And what's the deal with your production company's name, Moxie Firecracker?

The name and how ridiculous it is? I blame that entirely on my partner. I had a company called Moxie Films and my partner had a company named Firecracker films. I had gone out of the country for the first AIDS film and we had to sign deal with Lifetime and needed name for the company so my partner put Moxie and Firecracker together and it just stuck ... because it is just such an extraordinary name.

Shares