Late in the afternoon on the last Friday in February, Elizabeth Blackburn received a surprise phone call from an aide in the personnel office of the White House. Since early 2002, Blackburn, a distinguished cell biologist at the University of California at San Francisco, had served on the President's Council on Bioethics, the panel President Bush convened to explore the charged boundaries between ethics and cutting-edge biomedical science. On the council, Blackburn was sometimes critical of the Bush administration's restrictive policies on embryonic stem cell research; now, the White House staffer told Blackburn, the council was letting her go. The aide gave no explanation for the decision.

Blackburn was not technically "fired" from the bioethics council -- she was just not reappointed for the council's new term. But Blackburn was one of only two members on the 17-person panel to suffer that fate -- and it turned out that the other member not asked back, William May, an emeritus professor of ethics at Southern Methodist University, had been planning to retire anyway. For Blackburn, the cause of the abrupt dismissal was obvious. "I think this is Bush stacking the council with the compliant," she told the Washington Post that afternoon, the first of many instances over the next few weeks in which she publicly accused Bush and the bioethics council of playing politics with science.

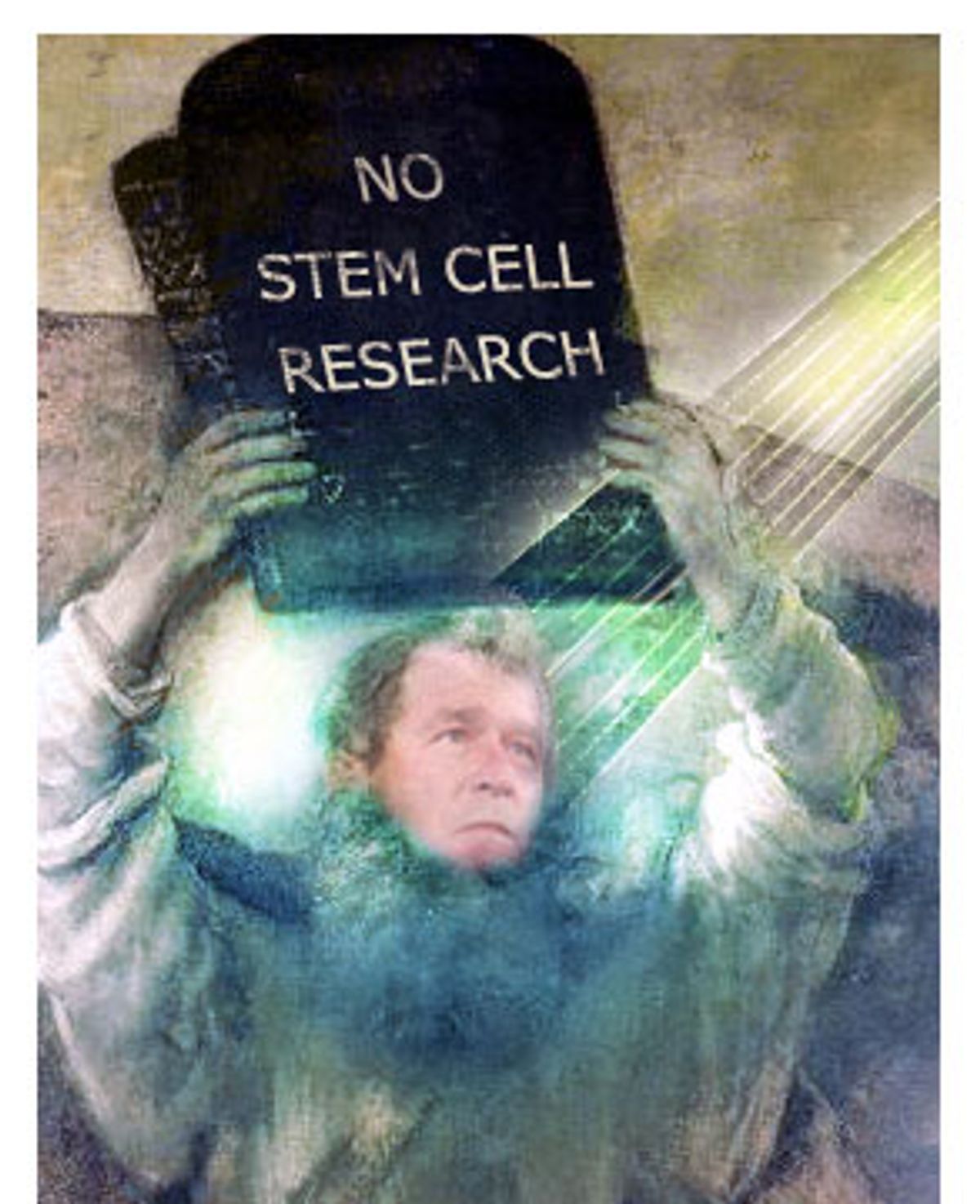

To critics of the Bush administration, Blackburn's analysis of the situation sounded unimpeachable. George W. Bush's unhappy relationship with science has been well documented. Indeed, just a week before Blackburn was let go, 60 prominent scientists -- including 20 Nobel laureates -- accused the president of routinely mangling scientific fact in the service of "partisan political ends." So just about everyone concluded that Elizabeth Blackburn was the latest victim of the Bush administration's partisan attacks on science. The story line was simple and compelling: Blackburn was a proponent of embryonic stem cell research, while Bush -- and his most ardent supporters -- was not. During a campaign stop shortly after Blackburn's dismissal, likely Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry told reporters, "A scientific panel ought to be chosen on the basis of science and on the basis of reputation, not politics."

The problem is that this simple story line is almost certainly wrong. Interviews with several members of the council -- including its chairman, University of Chicago ethicist Leon Kass -- and, more important, a review of its meetings and reports on stem cell research show Blackburn's charges of partisanship to be weak. It's not at all clear that Blackburn was dismissed for her views, rather than for her performance on the council (she was, for starters, serially absent from meetings, missing about half, more than any other member). And the council's reports -- particularly its lengthy inquiry into stem cell research, which the council released in January -- bear none of the biases she has accused the council of harboring.

The reshuffling of the President's Council on Bioethics is probably not, in other words, just another in a long line of Bush's scientific misdeeds. The real story of the bioethics council, the one that's been lost in the hail of political accusations, is that it has done some fascinating and admirable work -- and rather than letting the president off the hook, the council's report on stem cell research actually highlights the unsustainability of Bush's policy.

In its deliberations on embryonic stem cell research, the council has framed the issue as one offering no middle ground. There is no safe position in this debate, the council's report suggests: You either believe that very early-stage human embryos -- embryos that are just several days old -- deserve special "moral consideration" and should not be used for research, or you do not. You either believe that destroying these embryos is justified in order to realize the medical miracles that researchers say are possible with stem cells, or you do not. Bush has made clear that he believes embryos must not be destroyed. What's interesting is that his own council indicates that by the logic of Bush's position, the president will have a hard time ever changing or expanding his policy -- even in the face of amazing new advances -- without abandoning what he says is his considered moral position.

To scientists in the field, it's obvious that the president's current policy allowing for federal funding of research on only a small number of stem cell lines -- a policy conceived as a safe middle ground -- is quickly becoming untenable. Every day, researchers using private funding sources, and researchers in other countries, are making strides in stem cell science. And they are excited: To scientists, embryonic stem cells, which are harvested from very young human embryos, hold the promise of treating many human afflictions. Because such stem cells are in an "undifferentiated" state, they have the capacity to grow into many types of cells in the body -- muscle cells, brain cells, bone cells, heart cells, pancreas cells. Scientists imagine a future in which such cells could be grown in the lab and then implanted into patients, a procedure that they believe could treat Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, muscular dystrophy, cystic fibrosis, diabetes and perhaps dozens of other diseases.

"Right now, we can envision vast new ways of curing disease," says Michael West, a biologist who is the CEO of Advanced Cell Technology, a private biotech firm working on human cloning and embryonic stem cells. "When we talk about this in public, what this causes is an immense number of parents to write us saying, 'Can you help my child?' That's why we're always saying we should do this. We're 10 years from being able to help people -- but if we're 10 years away, that means we're only a few years from starting the trials."

But because the cells that currently receive federal funding are likely unsuitable for clinical therapies, it's difficult for scientists to conceive of such trials ever beginning under this president. And that's the real problem with Bush's stance. What's wrong with Bush's stem cell policy is not that he has stacked his council. The council is in fact in many ways irrelevant, because Bush, examining his soul, made his decision on stem cells a long time ago. Now the rest of us have to live with it.

From the moment the White House announced the members Bush had chosen for his panel on bioethics, in January 2002, the council has been criticized by advocates of embryonic stem cell research. Leon Kass, Bush's handpicked chairman, is at the center of the storm. Kass, who has a medical degree as well as a graduate degree in biochemistry, has written frequently of the "repugnance" he feels toward new biotechnologies and other manipulations of the body. Kass has problems with, among other things, "dissection of cadavers, organ transplantation, cosmetic surgery, body shops, laboratory fertilization, surrogate wombs, gender-change surgery," he wrote in his book "Toward a More Natural Science." In "The Hungry Soul," a philosophical meditation on eating, he expressed his dissatisfaction with "uncivilized forms of eating, like licking an ice cream cone -- a catlike activity that has been made acceptable in informal America but that still offends those who know eating in public is offensive," a citation that bloggers have had some fun with.

Bush picked other prominent conservative thinkers as members of the council -- the political scientist Francis Fukuyama, for instance, and the Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer. But the council can't be called a conservative group. Many of its members have no discernible ideological bent, and in its meetings (transcripts of which are posted on its site) and its reports, the council does not come across as homogenous; members are often at odds over small points and large ones, and Kass, as chairman, is keen to hear all sides.

"This has been the most interesting intellectual experience I have ever had," says Rebecca Dresser, a professor at the Washington University School of Law who is a member of the council. "That's because it's so diverse in terms of moral views and related political views."

Elizabeth Blackburn is the only member of the panel to publicly claim that the council was run unfairly -- and she did so only after she was let go. In a piece published on March 12 in the online edition of the New England Journal of Medicine, Blackburn wrote that when she was first invited by the White House to sit on the council, her inclination was to decline. She changed her mind only after Kass and Bush personally assured her that the council was eager to receive "the wisdom of a full range of experts," she wrote. But Blackburn says that members of the council soon found Kass unwilling to accept competing views. "Time and time again, other members of the council, including those who were initially skeptical about the potential of stem-cell research," urged "the chairman to account fully and fairly for the potential of this research to alleviate human suffering," she wrote.

Yet none of the members of the council, even those on Blackburn's side in the debate, would corroborate this view for Salon; several members praised Kass' management style. "I think Leon Kass runs the council very fairly," said William Hurlbut, a bioethicist at Stanford who is on the council. Blackburn declined to be interviewed for this article (an aide at UCSF said Blackburn wants to get back to her work), so it's hard to tell where exactly she saw Kass' slant come in.

In an article in the journal PLoS Biology, Blackburn and Janet Rowley, a cell biologist at the University of Chicago and a member of the council, cited a few specific problems they had with "Monitoring Stem Cell Research," the report the council produced on stem cells. Their complaints are technical, but they essentially argue that the council played up the promise of adult stem cells (cells that can be obtained without the destruction of embryos) and did not fully emphasize the promise of embryonic stem cells. In an interview with the Boston Globe, Blackburn went further, saying that the council's reports carried "this strong implication that medical research is not what God intended, that there is something unnatural about it."

"I regarded that as a bizarre comment about the council reports," says Gilbert Meilaender, a professor of Christian ethics at Valparaiso University and a member of the council who has tended to side with Kass. "I wouldn't mind being quoted as saying it was bizarre -- there may be many defects with the reports, but they do not carry the strong implication that medical research is not what God intended."

In an interview conducted by e-mail, Kass was equally critical of Blackburn's comments on the report. (Editor's note: Dr. Kass agreed to be interviewed on the condition that his response be published in its entirety.)

"Dr. Blackburn's quoted remarks about the stem cell report astonish me," he wrote. "For one thing, Dr. Blackburn signed the stem cell report without dissent, and did not take advantage of the opportunity (that she knew she had) to enter her personal dissenting statement into the report itself, disagreeing either in whole or in part. More important, what she says about the report itself is wildly mistaken. 'Monitoring Stem Cell Research' is an update on what has transpired in the past two years, both in basic and clinical research and in the ethical and policy debates surrounding the current federal funding policy. We commissioned seven scientific review articles -- on various aspects of current stem cell research -- from leading stem cell researchers, including John Gearhart and James Thomson, the discoverers of human embryonic stem cells, and those review articles are published in their entirety in the report. The staff-written chapter on 'Scientific Developments,' drafted by our scientific director Dr. Richard Roblin, was gone over not only by the members of the Council, including Dr. Blackburn; it was reviewed by three major outside stem cell researchers (including Dr. Gearhart), all of whom pronounced the treatment fair, careful, and accurate, and whose small suggestions for change we took in toto."

Kass said that "only on one point did we not accept Dr. Blackburn's own suggestions for change: Dr. Blackburn wanted the scientific chapter to issue in a political conclusion, namely, that we now know that embryonic stem cells are more valuable than adult stem cells. But we felt that the scientific evidence to date makes such a conclusion premature at best.

"The purpose of our stem cell report was not to lobby one way or the other but to monitor the state of the research. Anyone reading the transcripts of our meetings and the text of our report will find not one iota of evidence to support the claim that I or other Council members reject stem cell science, ignore its enormous potential to heal disease and relieve suffering, or proceed in these discussions on the basis of 'visceral reactions.' For the record, I am in favor of stem cell research and have said so publicly. It is easy to hurl charges; it is more responsible to read and judge on the evidence. Let people read the record and not rely on unsubstantiated and unsubstantiatable charges."

Kass is right; the council's report does not reject embryonic stem cell science, nor does it ignore the benefits that society might realize from stem cells. Rather, the report seeks to balance those benefits against the argument, made by many ethicists, that human embryos represent new life and are therefore "inviolable." In the ethics of stem cell science, this question goes to the heart of the matter: Is a 5-day-old human embryo actually new life? The council got nowhere near reaching consensus on the question. Instead, it found only unbridgeable differences, and its chapter examining the ethical debate surrounding embryos reads as if it was put together by a committee in total disagreement. Every statement is followed by a caveat, and in the end, the "on-the-one-hand this, on-the-other-hand that" argument leads nowhere. One is left feeling that the moral status of embryos will probably forever remain in dispute, constantly eluding compromise.

To scientists who favor embryonic stem cell research, a 5-day-old human embryo -- which is about a tenth of a millimeter in diameter, as big as a cross-section of human hair is wide -- is just an ordinary group of cells, of no more moral significance than any other biological material. "It's not a developing human being," says Michael West, of Advanced Cell Technology. "There are no body cells of any kind" in the embryo at this stage, West explains. "There are not even any cells that have begun to become any body cells of any kind."

In the first two weeks, the embryo's head-to-toe orientation has not yet been established. It does not have a nervous system, and no capacity for feeling pain (or anything else). Indeed, the young embryo has not yet reached the stage when it would divide into two if it's destined to become identical twins -- a fact that some have used to conclude that the embryo's "individuality must not yet be established," as the council's report says, because it "might yet become two embryos."

"The arguments that this is somehow a human being are unfounded and have no basis in religion or science," West says. "Those in the religious community who are saying this are basing it on nothing -- there's nothing in any religious document that says this is even against religion."

Others in the debate point out that embryos are already being destroyed or are slated for destruction as part of the routine business of in vitro fertilization. In the United States, there are more than 400,000 embryos in frozen storage in IVF clinics; nobody believes that the majority of embryos will ever become children. (Since many of them were stored because clinicians determined they didn't have a strong chance of becoming children, implanting them would actually raise ethical questions.) Why not harvest stem cells from these embryos? "Many conservative pro-life individuals should see this as a good thing," says Bob Goldstein, the chief scientific officer of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, which favors a looser policy on the federal funding of embryonic stem cell research. "It would be a benefit to somebody who's sick -- one could view that as a pro-life event. So we're not standing up and saying please destroy embryos. It's occurring in the natural course of events. We're saying if you're going to be destroying these embryos anyway or they're not suitable for IVF, let's use them for something good."

One study presented to the council estimated that if all of the embryos in storage were processed, scientists would yield about 275 stem cell types for research -- a quantum leap over the number of cell lines available today. But critics of embryonic stem cell science argue there is nothing intrinsic about "IVF spares" that allows us to destroy them -- they are, for these people, still developing human life, and we have a duty to protect (or at least not to destroy) life. In modern medicine, research on people is only acceptable if the subject has granted his "informed consent"; if we start working on embryos, opponents of embryonic stem cell research say, aren't we setting a bad precedent for the limits society should set on scientific experimentation conducted on human beings? Those who believe that even these young embryos deserve protection concede that there may be significant differences between us and embryos, but all of us, they point out, started out as embryos; genetically, in maybe the only way that counts, we are the same as embryos. So what if the embryos can't feel pain? The critics "suggest that it is dangerous to begin to assign moral worth on the basis of the presence or absence of particular capacities and features, and that instead we must recognize each member of our species from his or her earliest days as a human being deserving of dignified treatment," the council's report states.

What you conclude about the moral status of embryos would seem, in the end, to be a deeply personal decision; there is no right answer here, and the council's report should be commended for making that clear. The problem is, your personal opinion on the matter doesn't much count these days. Only the president's does.

It was in the summer of 2001 that George W. Bush wrestled with this question of the moral status of human embryos. After weeks of what the White House promoted as anguished deliberation, he announced his policy decision in a televised address from his ranch in Crawford, Texas. Bush said he'd spoken to many experts, and he encountered "widespread disagreement" in his quest for truth. Some people told him that because a 5-day-old "cluster of cells" in a dish could not develop on its own, it was not to be considered a new human being. Others said that it would be with a "heavy heart" that we destroy "the seeds of the next generation."

Bush sided with the second line of reasoning. "I believe human life is a sacred gift from our Creator," he said. Bush decided that no federal money would go to fund any stem cells harvested from embryos destroyed after his speech, on Aug. 9, 2001. But private companies had already created "more than 60 genetically diverse stem cell lines," Bush said, and he announced that the government would support research on those stem cells, "where the life and death decision has already been made." The policy "allows us to explore the promise and potential of stem cell research without crossing a fundamental moral line," he said.

The White House promoted Bush's policy as one of compromise, a moderate position in an area that was largely free of moderation; it embodied "compassionate conservatism." But it soon became clear there was nothing moderate about Bush's plan. While it was true that scientists had created "more than 60 genetically diverse stem cells lines," reporters discovered that only a handful of them were good enough for actual research. Currently, there are only 15 different kinds of stem cells available for scientists seeking federal research money. According to an unpublished report obtained from the National Institutes of Health by Rep. Henry Waxman, a California Democrat, the government's "best case scenario" is that only eight additional pre-Aug. 9 stem cell lines (for a total of 23) will ever be ready for research.

Since Aug. 9, 2001, dozens of new stem cell lines have been created by private laboratories around the world. Under Bush's policy, American researchers are prohibited from using federal money to work on the new lines. And even though many scientists would like Bush to expand federal money to these cell types, he can't; as the bioethics council says in its report, the only way for Bush to support expansion is by tacitly supporting the destruction of human embryos that occurred after he declared that such destruction went against the will of God. "Funding research on the currently ineligible lines derived after August 9, 2001," the council notes, "would not extend the logic of the policy or of the law, but rather contradict them both: it would be a difference not of degree but of principle."

In a sense, then, Bush is boxed in by his own moral decision, and so are we all. He is committed to his line of thinking, whatever the cost. As the bioethics council points out in its report, Tommy Thompson, Bush's secretary of health and human services, has actually said that "neither unexpected scientific breakthroughs nor unanticipated research problems would cause Bush to reconsider" his policy, because it is based on "a high moral line that this president is not going to cross."

What are the costs of Bush's stance? To stem cell scientists, the principal burdens these days seem to be measured in annoyance and inconvenience, and deeply held frustration over the speed with which therapies can be brought to patients. Resources are hard to come by. "The role of the principal investigator these days is begging for money, any way you can get it," says Jose Cibelli, a stem cell scientist at Michigan State University. In 2002, the National Institutes of Health provided just $10 million to researchers working on embryonic stem cells, and $17 million in 2003. For complex biomedical research, these sums are paltry. "We need at least 10 times as much as what they're giving us now," Cibelli says. "Of course, everyone says that; everyone will want more money for their own work. But I truly believe this is the future of medicine, and we're not doing enough to fund it."

Some research teams have been successful at raising large sums of private money. At Harvard recently, a team led by Douglas Melton, a biologist working on stem cell therapies for Type-1 diabetes (he has two children who suffer from the disease), managed to obtain funding from several private groups in order to create 17 new cell lines for researchers to work with. The task, which a researcher in the New England Journal of Medicine called a "tour de force," was not completed without a little bit of inconvenience; to comply with federal funding rules, Melton needed to keep his work on new cell lines physically separate from his other government-funded work. "Before Melton could begin," the Boston Globe reported, "he had a new lab built in the renovated basement of another building, far from the Petri dishes and microscopes that had been a part of his federally funded work in the past." Harvard has announced plans to raise as much as $100 million in private money to fund a stem cell center to foster work like Melton's, but such luxuries aren't available to every stem cell scientist. "Doug Melton might be able to run a Harvard institute with a lot of money," says Arthur Caplan, who directs the University of Pennsylvania's bioethics center. "Junior faculty might not be able to do that."

Another cost of the federal policy is that not only does it limit what current researchers can do, but it may also keep new researchers away from the field. "There's a more subtle effect, which is that young ambitious scientists are leery about getting into work that isn't funded by the government," says Harold Varmus, the CEO of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York and the director of the NIH under President Bill Clinton. "There's a general sense that if this is frowned upon by the government of the United States, scientists will say, 'Why would I want to go into that?'"

For scientists who choose to accept federal money by agreeing to work on pre-Aug. 9 stem cell lines (what researchers call the "presidential lines"), there are real limits on the kind of science that can be performed, researchers say. In his speech setting out his policy, Bush said he believed that his plan would allow researchers to "explore the promise and potential of stem cell research," but it doesn't seem as if they can do much more than that. "We can use them for basic research, but we're already starting to outgrow them," Evan Snyder, a stem cell scientist at the Burnham Institute in La Jolla, Calif., says of the pre-Aug. 9 stem cells. Because they were developed in the early days of the science, the presidential lines, says Snyder, are difficult to work with. "They are not really well characterized, somewhat unstable. It's very difficult for everyone to maintain the lines in the same way from lab to lab."

The bigger problem is that scientists are not sure that any actual therapies can be derived from the presidential lines. When scientists first began extracting embryonic stem cells in the late 1990s, they often kept them alive using "feeder cells" from mice. This was handy in a research setting, but it raises safety issues for clinical settings -- scientists fear that injecting stem cells prepared with mouse feeder cells could introduce mouse viruses into humans. "The presidential lines reflect 1990s biology, and we've learned so much more biology since back then," Snyder says. "We've developed ways that we can grow the cells without touching animal materials. We've developed lines that are not killed by antibiotics. We can even grow cells that don't touch any biologics at all." Snyder also points out that the presidential lines might only be useful in leading to therapies for a small number of people, "because the lines do not represent the diversity of America. The presidential stem cell lines come from embryos that were taken from IVF clinics -- they reflect families that have infertility problems that went to an IVF clinic. Many of them were in Wisconsin, so maybe they reflect what goes on in white America of Scandinavian descent. There's no guarantee that you can generalize these cells for black Americans or Asian Americans or anyone else."

Bush's position, then, would seem to offer the scientific community a bleak future: the promise of research pointing to cures for disease, but a built-in ceiling preventing researchers from ever using federal money to reach those cures.

Supporters of the president often point out that private funds can still be used to conduct research on embryonic stem cells, and valuable research is in fact going on at biotech firms. But the work is much impeded without the help of the federal government. "Frankly, from a selfish, capitalistic perspective, we're thrilled as can be that we get to hold all the patents and we don' have to pay royalties to Harvard or MIT," says Michael West, of Advanced Cell Technology. "As a human being, though, my life goal is to cure some disease before I grow old and die. I would prefer that we have to pay royalties to Harvard and MIT and we have a cure for diabetes and heart disease in our lifetime. We may have made a lot of money if we do it ourselves -- but it's far more important that we race as quickly as possible to the cures.

"Embryonic stem cells," West adds, "are magical. We've never had anything like this before, they are a whole quantum leap beyond adult stem cells. They're absolutely magical -- and that magic that the scientist sees in the microscope will filter out to the average U.S. citizen. Someday people will see this as a positive thing for mankind."

Shares