I met Barack Obama, the new Democratic nominee for the U.S. Senate from Illinois, eight years ago, at the home of mutual friends. Making introductions, our hostess suggested we had a good deal in common. Like me, Obama was an author -- he had recently published an autobiography, "Dreams From My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance" -- and he was a graduate of Harvard Law School, my legal alma mater. Unlike me, however, Obama was about to step into politics as a candidate for the Illinois State Senate from Hyde Park, home of the University of Chicago and a stretch of poor neighborhoods that run west from there. I spent much of the evening speaking to Obama and his wife, Michelle, yet another Harvard Law School graduate, and bought Obama's book the next day, which I praised when we met again. In the ensuing years I have stayed in touch with him, observing the ups and downs of his political career.

At the moment, Obama's career is way up, the result of one of the more impressive political victories in recent Illinois history. Sixteen months ago, when he entered the U.S. Senate race here, the odds seemed decidedly against Obama, who was running in his first statewide contest and whose Kenyan last name rhymes uncomfortably with Osama. Yet on March 16, Obama captured 53 percent of the vote in a six-person field, more than double the vote garnered by his nearest competitor, Illinois' comptroller, Dan Hynes. Hynes, who comes across as quiet, competent and likable, had been elected statewide twice before, and as the son of the former Cook County assessor, he is a scion of Chicago's Democratic machine, whose apparatus was fully behind him throughout the campaign. Despite that, Obama outpolled Hynes even in Hynes' home ward in Chicago. Coming in a distant third in the race was Blair Hull, who made half a billion dollars in the brokerage business and who spent $29 million of it on the primary. As the result of an early TV blitz, Hull led in the polls, until a past that included spousal-abuse charges and chemical-dependency treatment sank him.

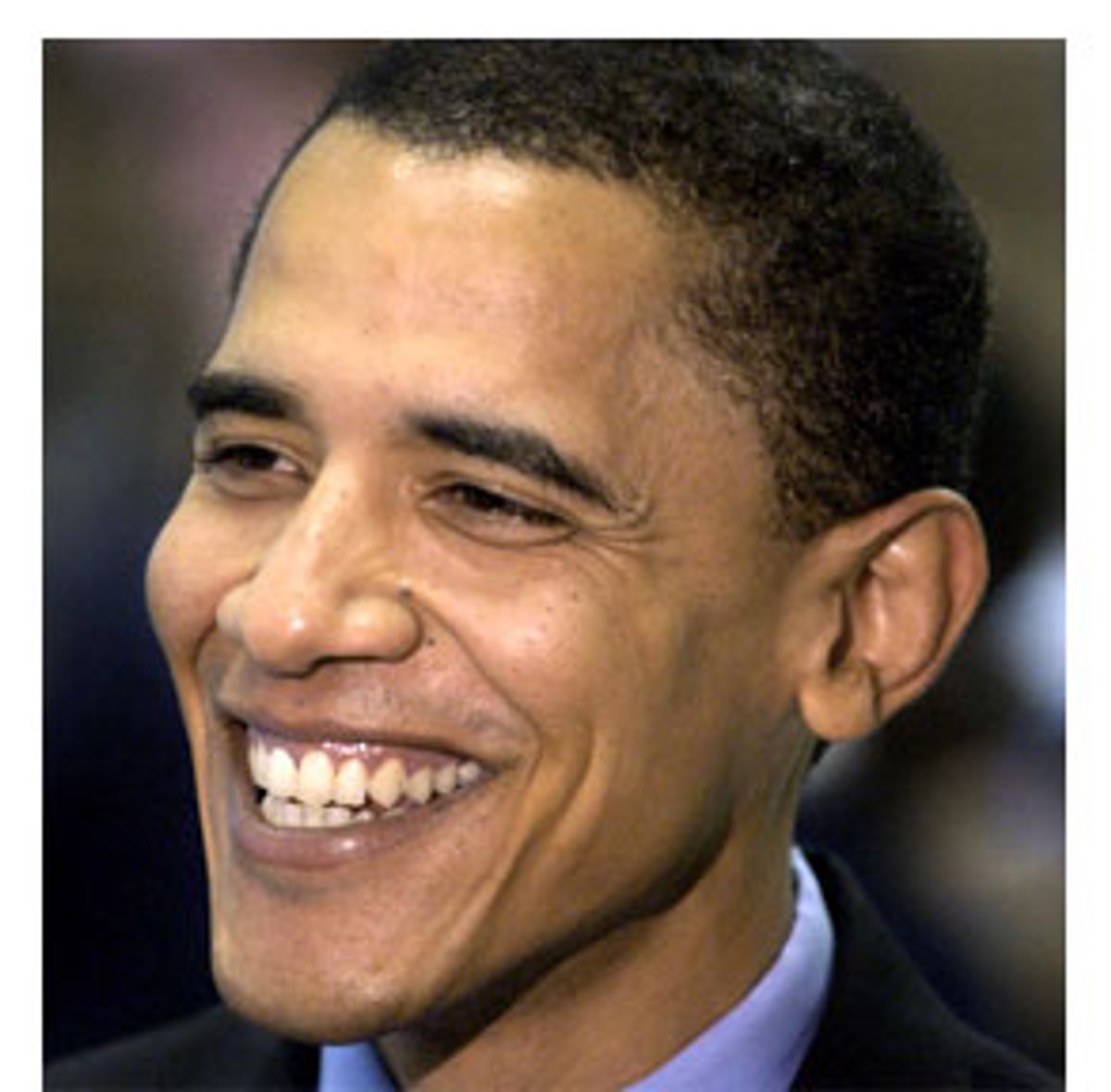

Barack Obama now becomes the national flag-bearer for Democratic hopes to retake the U.S. Senate, which the Republicans hold by one vote. He is hoping to win the seat being vacated by Republican Peter Fitzgerald, whose quixotic maneuvers in the Senate left him bereft of support at the end of one term. Handsome, poised, intelligent, Obama has already begun to attract national attention, as he moves toward becoming only the third African-American elected to the Senate in more than a century.

Having known Obama since the inception of his political career, I have watched his rise closely. We are hardly intimates, but we are certainly warm with each other, and I have been a political contributor and supporter of his. No one in these circumstances would regard himself as unbiased (except perhaps Justice Antonin Scalia). That said, I have many friends whose company I savor whom I would not commend for service in the U.S. Senate. Obama, though, has matured in plain view. He has gone from someone impatient with the legislative process to an effective and respected leader in the Illinois Senate, and from a candidate who once seemed to be getting ahead of himself politically, and whose base in the black community was shaky, to a figure who appeals to voters of all hues.

Obama is the early favorite in the race. Illinois has trended decidedly Democratic in recent years: Gore carried the state handily in 2000, and in 2002, when the Republicans scored elsewhere, the Democrats swept in Illinois, reelecting our senior U.S. senator, Richard Durbin (another rising Democratic star), capturing both houses of the General Assembly, and electing Rod Blagojevich as the state's first Democratic governor in 30 years. There is no sign of a turnaround. More than twice as many Democrats as Republicans voted in the primary elections on March 16, even though the Republicans ran a seven-person race for the Senate nomination that was highlighted by a barrage of TV advertising as a group of multimillionaires squared off against one another. If Obama capitalizes on these advantages and wins, he will become the highest-ranking African-American elected official in the country.

Obama's biography is both intriguing and inspiring, an American story for the 21st century. The résumé detail that initially caught wide attention was his election in 1990 as the first African-American president (that is, editor in chief) of the Harvard Law Review, the premier legal academic publication in the United States. Banish any lurking thought of an affirmative-action wind at his back. Exams at Harvard Law School are graded blind, and Obama graduated magna cum laude (also unlike me.) He has taught for many years at the University of Chicago Law School, along with many of the country's preeminent legal scholars.

But academic excellence is only one part of his story. "Dreams From My Father" is a beautifully crafted book, moving and candid, and it belongs on the shelf beside works like James McBride's "The Color of Water" and Greg Williams' "Life on the Color Line" as a tale of living astride America's racial categories. No other figure on the American political scene can claim such broad roots within the human community. Obama is the very face of American diversity.

His parents met as college students in 1960. His father, also named Barack Obama, was from Kenya's Luo tribe, the first African exchange student at the University of Hawaii. His mother, Anna, had gone to Hawaii from Kansas with her parents. Even in Hawaii's polyglot culture a black and white couple remained at best an oddity in 1961, when Obama was born; at the time miscegenation was still a crime in many states. Nor was Obama Sr.'s marriage welcomed in Kenya. Under those pressures, Obama's father departed when Barack was 2 to pursue his Ph.D. at Harvard, leaving his son with mother and grandparents. When Obama was 6, Anna remarried. Her new husband was Lolo, an Indonesian oil company manager, and the new family moved to Djakarta, where Obama's sister Maya was born. (Obama describes her looks as those "of a Latin queen.")

After two years in a Muslim school, then two more in a Catholic school, Obama was sent by his mother back to her parents' home so that he could attend Hawaii's esteemed Punahou Academy. Living with two middle-aged, middle-class white people (his grandfather was a salesman, his grandmother a bank employee trapped by a glass ceiling), Obama struggled as an adolescent with the realities of being African-American, an identity that was in part imposed by others, and yet one he also embraced as the legacy of a father for whom he yearned but with whom he enjoyed only sporadic contact. He attended California's Occidental College, then Columbia. After graduation he moved to Chicago, where he worked for a number of years as a community organizer on the city's South Side, employed by a consortium of church and community groups that hoped to save manufacturing jobs.

Obama's father died in a traffic accident in Nairobi in 1982, but while Obama was working in Chicago, he met his Kenyan sister, Auma, a linguist educated in Germany who was visiting the United States. When she returned to Kenya in 1986 to teach for a year at the University of Nairobi, Obama finally made the trip to his father's homeland he had long promised himself. There, he managed to fully embrace a heritage and a family he'd never fully known and come to terms with his father, whom he'd long regarded as an august foreign prince, but now realized was a human being burdened by his own illusions and vulnerabilities. With that, Obama began to feel more accepting of himself. Harvard, law practice, teaching and politics followed.

As a legislator and politician, Obama has had both missteps and triumphs. During his first year or two in the Illinois Legislature, he sometimes found it hard to connect with colleagues who occasionally seemed put off by his credentials, and even harder to get anything done. In 1999, after only three years as a state senator, Obama decided to challenge Bobby Rush, the longtime congressional representative, who had begun his public life as a leader of the local Black Panther Party. More than one veteran Democrat claims to have told Obama it was too soon to move on to another office, but he was eager to take on Rush, whose rhetorical victories have often outpaced his achievements as a representative. But Rush thrashed Obama in the 2000 Democratic primary, leading political insiders to speculate that Obama, with his Ivy League manner, was "not black enough" to make Chicago's large African-American community his political base.

The same period also produced Obama's most substantive political gaffe. Richard M. Daley, Chicago's Democratic mayor, had forged an alliance with the Republican governor, George Ryan, to promote a gun-control bill fiercely opposed by the National Rifle Association and the Republican majority leader of the state Senate. Intense pressure was mounted by both sides, and as final consideration approached at year's end in 1999, the nose-counting indicated that a few votes one way or the other would control the bill's fate. Despite being committed to the measure, Obama reportedly ignored entreaties to return from Hawaii, where he was visiting his family. The gun-control measure went down to defeat, and Obama's subsequent explanation for his absence, saying that his younger daughter had fallen seriously ill, did not play well either with the press -- the Chicago Tribune blasted him as "gutless" -- or his fellow politicians, who'd left plenty of sickbeds and vacations in their time for the sake of public duty.

In retrospect, that walk through the political shadows proved a turning point in Obama's career. He recommitted himself to the Illinois Senate, where his intelligence and his growing savvy about the legislative process were combining to make him increasingly formidable. When Democrats took over the chamber in 2003, Obama won General Assembly approval of 26 bills, including legislation to expand healthcare benefits for uninsured children and adults, an earned income tax credit for low earners, and major criminal justice reforms.

The latter measures were of particular interest to me. In the summer of 2002, Obama had called me to get together to talk about death-penalty reform. For more than two years, I had sat as one of the 14 members of the Commission on Capital Punishment, a body that Gov. Ryan had appointed in 2000, after declaring a moratorium on executions in Illinois because of a growing record of mistakes in the capital process, most notably the death sentences of 13 individuals who were subsequently exonerated. In April 2002, the commission issued its report, including 85 recommendations for reform of Illinois' laws.

Despite Ryan's support for our recommendations, resistance to the measures ran deep in the General Assembly, due in large part to the barely tempered rage that had been been expressed by many Illinois prosecutors. After appearing at legislative hearings that spring, I grew skeptical that any of the proposals would become law. When I met Obama the following summer, he went through the recommendations with me, analyzing which proposed reforms had a chance of passing and which did not. I was impressed not only by the shrewdness of his analysis but also by his lack of rancor about those who disagreed with him and, most of all, by his refusal to bow to conventional wisdom about what was possible. There were a couple of provisions that had essentially been pronounced DOA, where I remember Obama saying, We might be able to do something there.

At the end of the conversation, we talked about his political future. I had heard he was thinking of tossing his hat into the ring against Peter Fitzgerald, who had not yet announced that he would not seek reelection. At that time, Barack was still trying to assess how he would play among his potential Democratic opponents. By the next January, he had decided he was going to run.

In spite of our friendship, I remained on the fence about whether to support him, leading to several good-natured but frank exchanges between us. Barack's loss to Rush had made me skeptical about his chances of winning and his ability to take on an even larger campaign. I was concerned that if he lost again he'd damage his long-term prospects, and I also did not want to see the Democratic primary develop into an ugly internecine struggle, especially one with racial overtones that might threaten the Democrats' chances to beat Fitzgerald, whom everyone perceived as vulnerable. Nonetheless, watching Obama for a few months, and speaking with him periodically, convinced me that this was his time.

For one thing, he had scored a legislative success I regarded as little short of astounding, bringing prosecutors and the police to the table and passing a bill embodying one of the Capital Punishment Commission's most pressing reform proposals: a requirement that police electronically record all phases of the interrogation of homicide suspects. The measure was likely to significantly reduce the number of coerced and false confessions in murder cases. Obama had worked hard and eventually persuaded the law-enforcement community that the change would also enhance the prosecution's chances in the vast majority of cases where confessions are genuine.

Obama also convinced me, over time, that he knew how to run a winning campaign. Notwithstanding Rush, whose opposition was vehement but predictable, Obama was able to solidify his standing in the African-American community. He worked the black churches and won the support of the Illinois Senate leader, Emil Jones, one of the state's most commanding and effective African-American politicians. Obama also got the backing of Jesse Jackson and Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr. In a multi-candidate primary, bringing out a large African-American vote might have been sufficient for Obama to obtain the nomination. But to win in November, Obama knew he had to be more than "the black candidate." Accordingly, he courted the liberal Democratic constituencies along Chicago's Lake Shore, from Hyde Park all the way north to the suburbs where I live. From the start, he tapped into the same energy that Howard Dean was finding, the abiding anger of so many Democrats with both George W. Bush's policies and with those Democratic politicians who seemed intent on reinforcing Bush's supposed popularity by venturing no criticisms of him. Obama blasted Bush's tax cuts for the wealthy as reductions "nobody needed and nobody asked for," and he also spoke out prominently against the war in Iraq even before he had entered the Senate race.

Last summer, my wife Annette and I held an event for Barack in our home to introduce him to friends. He was poised, conversant with the issues, and disarmingly candid. He correctly predicted that evening that if he won the primary, he would emerge as a candidate whose unique credentials would attract support from across the country. That night, he did what every successful politician must do: He persuaded virtually everyone in that room that he could win and, even more important, that he deserved to.

Obama continued to run a sure-footed, disciplined campaign. He can sound like a policy wonk in the Clinton mold when that's called for, but he knows better than to show off, and he sticks to short answers. His casually straightforward manner is especially well-suited to TV, where I thought he became increasingly effective as the months wore on. (I interviewed him as a supporter on a local access channel, and despite my years of TV appearances as author and lawyer, was dazzled by how much more relaxed and articulate he was than I seemed to be.) When we met about six weeks before the primary, he confessed that he was beginning to be concerned about Blair Hull's massive financial advantage. But even then, Obama was clearly clicking with a broad cross-section of Illinois voters. At the endorsement session of my local Democratic organization, where both Hynes and Obama had spoken, all of the local elected leaders in the area took to the floor to back Hynes. The rank and file ignored them. Obama got the endorsement with 78 percent of the vote. In the weeks that followed, as Hull faltered, it was clear that Obama was surging. All three major papers in the Chicago area and many others throughout the state ended up supporting him.

Although those same papers have now dubbed Obama the early favorite in the general election, he has plenty of work cut out for him. In 1992, Illinois sent Carol Moseley-Braun to the Senate, and she undoubtedly extinguished any inclination Illinoisans might ever have had to cast a vote as symbolic blow for racial equality. Although Moseley-Braun is a person of substance, often eloquent and blessed with a million-megawatt smile, she was recklessly indifferent to details in her personal and political life throughout her time in the Senate and left many who'd supported her with the taste of ashes. In an America inclined to racial stereotyping, many Illinoisans can be expected to cast a wary eye on Obama as he seeks the same seat Moseley-Braun lost.

Moreover, Obama's Republican opponent, Jack Ryan, has his own star power. Ryan is very rich (a former partner at Goldman Sachs), very glamorous (formerly married to "Boston Public" TV star Jeri Ryan) and very smart -- he too went to Harvard Law School, and to Harvard Business School as well. But Ryan has exposed flanks. He lacks experience in public life. And he will have to deal with the fallout of his divorce from Jeri. Records of the Ryans' child-custody proceedings are sealed at the moment. Rumors abound that they contain ugly details, an impression reinforced when the judge in the case initially rebuffed a request to seal the file, stating that the move appeared intended only to protect Ryan's political ambitions. The Chicago Tribune has sued to gain access, and Ryan's steadfast insistence on keeping the records private cut deep into his lead in the waning days of the Republican primary campaign.

More telling in the end will probably be Ryan's extreme conservativism in a state where the far right has seldom prevailed. Durbin, for example, voted against Bush's tax cuts, returned to Washington to vote against the Iraq War resolution in the midst of his reelection campaign in 2002, and captured more than 60 percent of the vote against an able Republican opponent. Jack Ryan is ardently pro-life and pro-gun, favors even lower taxes, and disapproves not only of gay marriage but even of domestic-partner benefits. And then there's the practical problem that Jack Ryan bears the same last name as George, whose estimable courage as Illinois governor did nothing to abate the enormous public revulsion with him, which stemmed from a corruption scandal during Ryan's prior tenure as the Illinois secretary of state and has now led to his federal indictment. The Republican gubernatorial candidate who lost to Blagojevich was also a Ryan, and he found his last name such a millstone that he spent thousands trying to become the political equivalent of Prince, advertising himself as just plain Jim. The "Jack" on the campaign posters of this year's Ryan is already gigantic, but the fact that the Republicans have done this to themselves yet again has to tickle many Democrats who thought their party alone was visited by the impulse for self-destruction.

Adding it all up, the smart money has to be on Barack Obama to win in November and thereby to become a pivotal American leader. To be young, black and brilliant has always appeared to me to be one of the more extraordinary burdens in American life. Much is offered; even more is expected. You are like a walking Statue of Liberty, holding up the torch 24 hours a day. Yet Barack Obama, who spent his early years coming to terms with his heritage, is in every sense comfortable in his own skin and committed to a political vision far broader than racial categories.

Because they work for George W. Bush, and therefore cannot be regarded as influential political figures in the African-American community, Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice may be the first blacks in government whose race is an afterthought in the public mind. If he wins, Barack Obama will also answer to a constituency that is principally white. As a result, he may become the first black Democrat able to rise above race in the fashion of Powell and Rice, and in doing so become the embodiment of one of America's most enduring dreams.

Shares