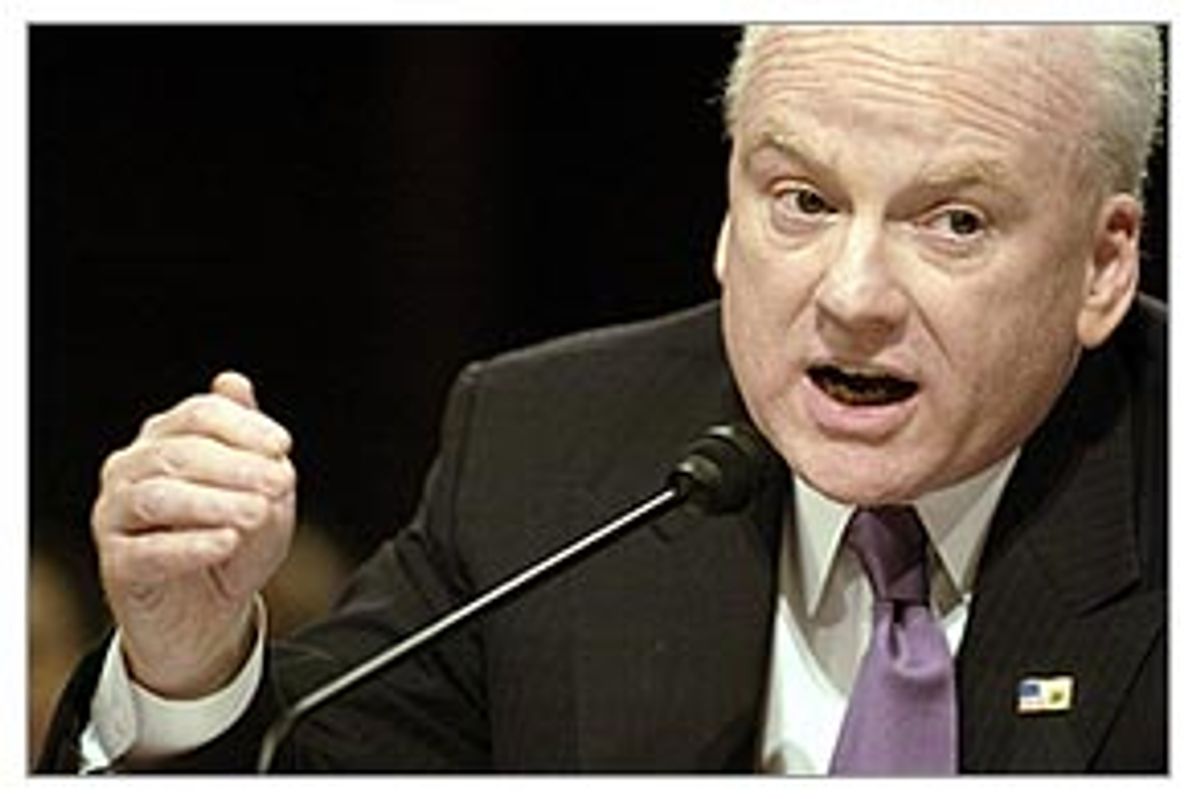

Within hours of former counterterrorism chief Richard A. Clarke's testimony before the 9/11 commission, where he discussed how resources spent on the Iraq war undermined the war on terrorism, President Bush acknowledged that his rationale for the war -- Saddam Hussein's presumed possession of weapons of mass destruction -- remained absent. Bush's admission took the form of a comic monologue before about 1,000 black-tied members of the Radio and TV Correspondents Association gathered for its annual dinner. The lights dimmed and Bush presented a slide show of photographs of himself peering out of windows and looking under furniture in the Oval Office. "Those weapons of mass destruction have got to be somewhere ... nope, no weapons over there ... maybe under here?"

With each gag line the press corps roared. Bush was acting as the college fraternity house president that he once was, and the journalists performing as pledges eager for acceptance by the Big Man on Campus. "I'm the commander -- see, I don't need to explain -- I do not need to explain why I say things," Bush told Bob Woodward in "Bush at War." "That's the interesting thing about being president."

Through its laughter the press corps didn't seem to grasp that the joke was on them. The problem is not that Bush's jest was inappropriate and tasteless -- the widow of David Bloom, the NBC reporter who died in Iraq, had tearfully preceded Bush on the platform. It is not that much of the media, including elements of the quality press, had been complicit in the carefully choreographed disinformation campaign in the rush to war stage-managed by Ahmad Chalabi and the Bush administration. Rather, it is that the press is accepting of Bush's radical undermining of the long-established arrangements of Washington, including the demotion of the press's own role, by breaking the off-the-record rule in order to have a weapon to use against Clarke.

The new rules of the game are that there are no rules of the game. In the preface of his book, "Against All Enemies," Clarke wrote that he expected an assault on his reputation from the "Bush White House leadership," who were "adept at revenge." Clarke had observed the politics of intimidation become standard operating procedure. Former ambassador Joseph C. Wilson, who, at the administration's behest, looked into the claim that Saddam was seeking uranium in Niger and concluded it was bogus, was subjected to a sustained attack that included outing the identity of his wife, a covert CIA operative, a federal felony now under investigation by a special prosecutor. Former Secretary of the Treasury Paul O'Neill had revealed that an invasion of Iraq was being pushed from the earliest days of the administration, and instantly he became the target for personal vituperation. Richard S. Foster, the chief actuary for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, was threatened that if he told the Congress the actual cost of Bush's Medicare bill while it was being considered he would be fired. So Clarke knew the new rules.

Throughout the long day that ended with the president's WMD joke, the White House directed strikes on Clarke's integrity. It declassified an off-the-record background briefing Clarke gave in 2002, when he had been ordered to put a "positive spin," as he put it, on Bush's pre-9/11 terrorism record in response to a critical report in Time magazine. The White House press secretary read portions of the briefing aloud and out of context. National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice, whose neglect of terrorism was among Clarke's revelations, summoned reporters to her office to point to the background briefing and call his story "scurrilous." While she was putting a stiletto into Clarke, the background briefing paper was shuffled by her press office to Fox News to broadcast as Clarke was testifying. Republican members of the 9/11 commission waved the paper at him, and much time was consumed by his explanation of how as a staffer he was acting properly, like a lawyer representing a client, and why his briefing was not at odds with his information now.

This selective declassification shattered the implicit agreement that permits officials to interpret to journalists with some candor. Clarke's scourging was a signal to professionals in government of what will happen if they ever in the future contradict the Bush line. Those who dare are treated as enemies of the state, as Clarke predicted he would be. Clarke's account of the failures of policymaking reflects his sense of duty. The breakdown in the credibility of Bush's presidency time and again has been defended by smear campaigns. But the press has reacted as though this event does not involve its status and craft. Not one news organization considered trying to uphold the old rule by threatening to reveal Bush administration officials who gave background briefings unless the White House repudiated its act against the accepted convention that makes informed journalism possible.

The Clarke episode is symptomatic of a systematic abuse of power. Reality is raw and dangerous -- better to laugh along.

Shares