When Reena, 24, worked at a customer service call center, she found herself hawking magazines to Americans in the middle of the night -- Americans none too happy to hear from her.

"I had one who said, 'Go back to your own country,' because she thought I was in the U.S.," Reena remembers. "I said, 'Ma'am, I am in my own country."

She quit after eight months.

Her friend, Deepa, 23, worked in a call center for just a few weeks. The verbal abuse from angry customers was too much: "If you had been a god, you could take any shit. But you are a human being. How long can you take it?"

The same monotony that people working the phones in the United States complain about afflicts their counterparts on the other side of the world, too: "In a call center, you can survive just a year or two and not find it boring," says Deepa.

There are other hidden costs to the Indian telemarketer grind. "You work in shifts. When you are awake, your family is sleeping, and when your family is awake, you are sleeping. You have money, but you can't actually enjoy that money," says Reena.

"Say I have spoken to 10 irate customers," adds Dwpa. "I'm definitely going to be in a very bad mood. And that same bad mood, I'm going to take it home. And it's going to come out at my loved ones. So, what's the use of that much money?"

In Mumbai (a city that everyone still calls Bombay) 10,000 to 12,000 rupees a month -- about $230 to $275 U.S. dollars -- is an attractive lure for recent college graduates in this mega-metropolis, home to the glamour and lucre of the Bollywood film industry as well as the largest slums in Asia. To put that sum in context, a freshly minted MBA starting out in an insurance company makes about 14,000 rupees a month.

But despite the big bucks that call centers offer, by the industry's own conservative estimates, annual attrition for such jobs in India is 30 to 40 percent, according to the National Association of Software and Service Companies. Some turnover can be explained by experienced "agents" job-hopping from one firm to another to increase their wages; the sector continues to grow at a rate of more than 20 percent annually.

Today Reena and Deepa are programmers for an I.T. (information technology) services firm called Webodrome. Their office occupies part of a hall on the ninth floor of a 14-story office building in Mumbai's Nairman Point district. A swath of the Arabian Sea is visible from the window of the small meeting room where engineers often eat lunch.

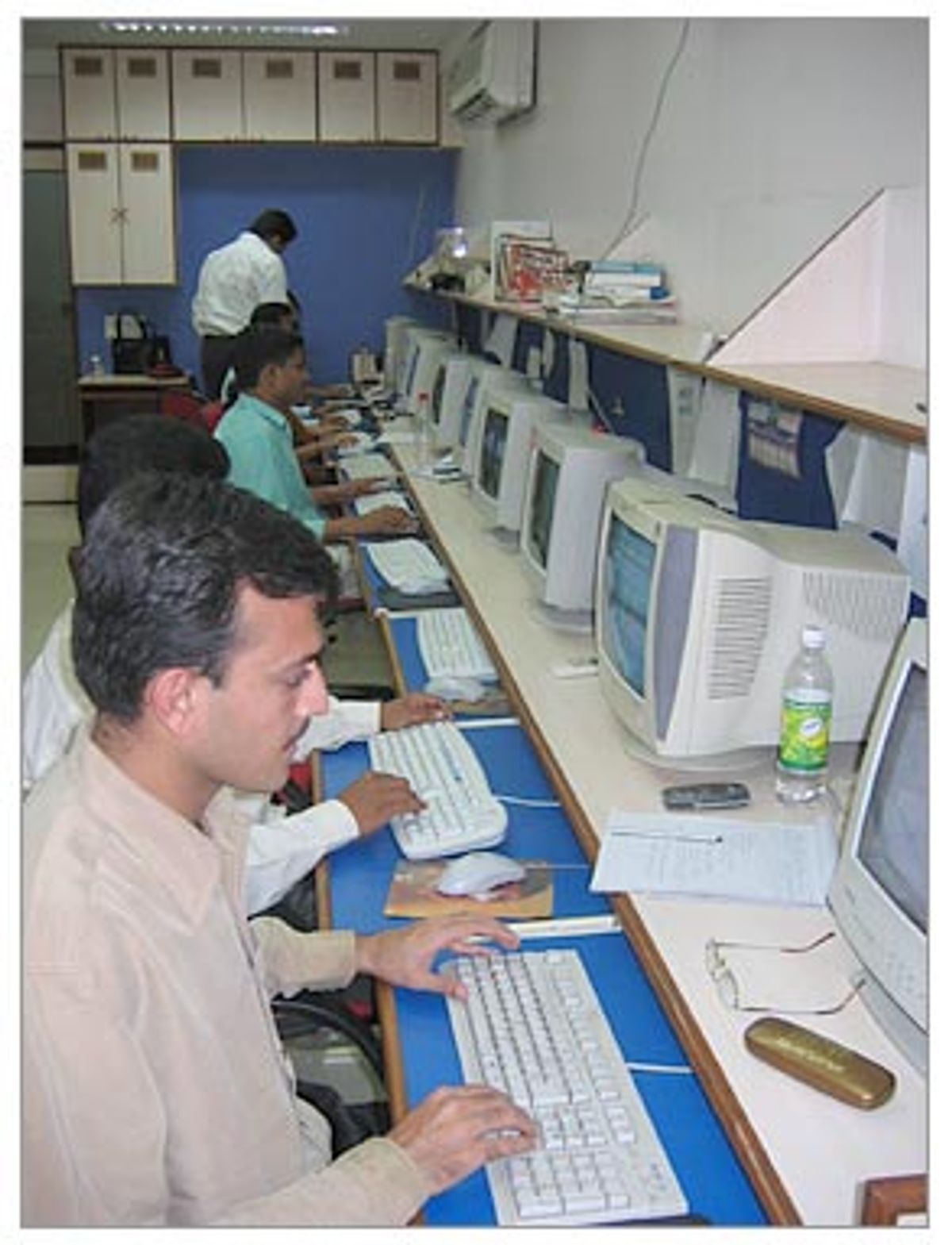

Around 30 people work in Deepa's crowded office, writing code in ASP, Java, VB.Net, PHP and many other technical lingua francas. They spend about nine hours a day coding for American, European and Canadian companies -- projects outsourced to India at costs of about half of what first-world programmers would charge. The starting salary at Webodrome can be as little as half of what the call centers dangle, but Deepa and Reena are here for the promise of a better career -- and more money -- in the longer term.

I came to this small firm because one of its co-founders, Amit Doshi, read a story titled "White-collar Sweatshops" I had written last July. In the story, I had focused on the increasingly angry reactions expressed by American programmers on the topic of the globalization of the tech job market. Doshi bluntly informed me that I understood nothing about what outsourcing means to his employees. He wrote: "First, right off the bat, I take a great deal of offense when you call what I do for a living running a sweatshop."

True, his company's offices look crowded by Western standards, but they don't exude the atmosphere of piecework oppression that rows of women hunched over sewing machines do. The programmers certainly are not complaining -- coming to work, they told me, is an exercise in "total freedom." They have their own ideas about what makes a job good or a bad, what exploitation is, and what's simply beneath their dignity. Phanindra, 24, another Webodrome engineer who is also pursuing an MBA, says he, for one, would never work in a call center: "I'd be a hawker on the roadside before I would do that," he says, drawing laughs from his coder colleagues. "Self-esteem is something you should possess."

Nairman Point is a once ritzy commercial address that's seen better days.

Years ago, office real estate in this neighborhood of Mumbai was some of the most expensive in the world, selling for about 25,000 rupees a square foot,

"If you were in corporate, you had to be here. You had no other choice. Now, there are quite a few other places," says Minesh Shah, 29, Doshi's co-founder. As the infrastructure in Mumbai has improved, newer, sleeker offices have opened up farther away from the city's center.

Real estate prices have now fallen to about 7,000 rupees a square foot, and those faded fortunes show in the smudged hallways scrawled with incongruous "Jesus loves you" graffiti on the ninth floor.

When Doshi and Shah started the company in 1999, they had to fib to the local bureaucrat that Webodrome was the name of a university in the United States they'd both attended, since made-up names are not allowed as official company names. When they moved into this building, they had to bribe the phone and electricity guys to get those services installed.

While Doshi and Shah live within a few minutes' drive of the office, and party in the tony Colaba district, many of the 30 engineers who work for them travel every day by train from far-flung suburbs for more than an hour and a half. They represent India's educated middle class; their parents work in a range of businesses, including shoe manufacturing, wholesaling and retailing, or the garment biz. For some, programming is no new fad: one Webodrome engineer's father used to make his living programming in COBOL.

The programmers travel by commuter rail cars so crowded that local newspapers condemn them as "inhumane." That's not just an instance of the giddy hyperbole the Indian press is famous for: The trains are so ruthlessly packed that in early March a commuter fell from one, dying from head contusions suffered in the fall.

By the time these trains reach Churchgate station in Mumbai at rush hour, arriving once every three minutes, passengers are literally hanging out the doors. Women ride in "ladies only" cars up front, but they're hardly as genteel as that turn of phrase sounds -- a crush of brightly colored fabrics, the packed bodies of hundreds of commuters, bulge from cars designed to hold a fraction of the number of occupants forcing themselves in.

Don't even think about sitting down or reading or talking on your cellphone. Breathing is hard enough. "It's much too crowded," says Sandeep, 28, a programmer at Webodrome, who travels two hours on these trains both to and from work. The programmers joke that the trains are so packed that buttons pop off passengers' clothes.

But "there is no point in grumbling," says Piyush, 28, another programmer here whose rail commute is even longer -- two hours and 15 minutes, both morning and night.

"We are tolerant. We are the sons of Gandhi," explains Phanindra, drawing a big laugh from his colleagues. He travels a comparatively brief one-and-a-half hours each way.

Doshi explains that some of his programmers had to travel so far to get to work that the company helped them rent a one-bedroom apartment across the street from the office. Four young men -- three of them Webodrome employees -- now live there, sharing the 10,000-rupee-a-month rent.

After one hears how they get here, their office looks, even feels, less crowded. How do they describe the workplace atmosphere?

"Total freedom," Sandeep says.

"There are no restrictions," adds Reena.

"No politics, no hierarchy, basically," adds Deepa. "It's like a second home. I love to come to my workplace."

Because the firm is relatively small, the programmers interact directly with both their bosses and the clients, chatting with them on MSN Messenger. Working via instant messaging makes it easy to keep a record of what has been discussed, and isn't anywhere near as expensive as an international phone call.

The three bosses here, Doshi, Shah and Ariz Kohli, 30, solicit business on the Web, sending out e-mails to potential customers that boast "Our offshore development center in India enables us to offer very competitive pricing." When the clients tell them what they want, the programmers estimate how many hours it will take, and the projects are priced by the hour. Clients pay $10 an hour for basic Web design, $15 for database programming, and $20 for more advanced coding, like cellphone or .Net work, for projects ranging from $2,000 to $20,000 or $30,000. That allows the programmers to be billed out at an average of $3,000 a month, Doshi explains.

The programmers work from about 10:30 or 11 a.m. to 8:30 or 9 p.m., to accommodate both their commute and the time difference with clients. Everyone gets Saturdays off, unlike other firms that require every other Saturday or every-Saturday hours. And the atmosphere is more casual, they say, than a typical firm in Mumbai. You'll find programmers listening to music on headphones at their desks and occasionally chatting with friends via instant messaging.

But they'll code all night to meet a big deadline. "Last Friday night, we had three people here until 5 a.m. in the morning. They had a big deadline, and they had to finish, and they spent the night here," says Shah, adding, "They're not going to come to me this morning, and say: 'I worked three extra hours. I want overtime.' They know it's part of their job."

Doshi says it's a two-way street: "If you need to get something done, it's your job to get it done. And if you don't have that much work to do, then we're not going to make you sit in the office in front of the computer for nothing."

And they're getting valuable experience; colleagues of theirs have recently been hired away, doubling their salaries by moving to huge firms like Tata Consulting Services and British Telecom.

When Webodrome places a 10-centimeter ad in the Times of India, advertising for programmers, the company will receive about 300 or 400 responses, 200 of which will be recent college graduates, Doshi says. Technical colleges send their students as unpaid interns to Webodrome to get trained for credit.

The surplus of recent college grads looking to get their foot in the door is often exploited by unscrupulous companies. Some small firms pay only 1,000 or 2,000 rupees a month, even after a six-month tryout. Other firms require a deposit of tens of thousands of rupees before they will hire you, which is repayable according to a contract, only after two years of service, says Dwpa. You cannot leave the company during that contract period, or you forfeit the deposit.

And some just demand really long hours -- 12 hours a day, not including the commute: "There are many companies that are doing this," says Deepa."That's the level of exploitation. If you're going home at 9 p.m. at night, they still expect you to come in sharp on time. Whether you reach your house at 12 at night, they do not care." She says when they work late at Webodrome, the managers aren't watching the clock the next day.

"In our jobs, when we get back home, our family is there. We can sit with them for an hour or two," says Reena. "We can have dinner with them and we can spend our weekends together, so that matters a lot."

Most evenings, the programmers take the long train rides home to their families, but on an occasional Friday night, they'll go out to dinner after work together, grabbing a bit at a Chinese, South Indian or fast-food joint: "any happening hangout."

Shah and Doshi enjoy a different sort of nightlife.

Shah spent three years studaying and working in the United States, receiving his MBA at Clark University in Worcester, Mass. Afterward, he says, he didn't want to stay, in part because he found the American lifestyle too lonely. Now, after work, he gets together with friends from school every single day, sometimes for dinner or a movie, but often just to hang out for an hour at the local Barista -- India's chain-store answer to Starbucks.

The half dozen guys, who include the entrepreneur behind a Web match-making site, don't actually go into the Barista. They stand outside to smoke and chat. A cigarette hawker who does business from a small table on the cracked street in front of the cafe sells them individual smokes and mints. The nightly boys' club convenes at 8:30 for about an hour and takes place in sight of Mumbai's World Trade Center, a much shorter version of what used to stand in New York City.

Doshi's father was a COBOL programmer who went to the United States to study technology. Doshi is an American citizen but returned to India at age 8 with his mother after his father died, then went back to the U.S. at age 17 for college, returning again to India six years later.

On a typical night out, you'll find him meeting friends, such as an editor at Elle India and the scion of a Mumbai jewelry dynasty at the upscale bar-restaurant Indigo, where techno blares while dinner is still being served at 1:30 a.m. Chelsea Clinton recently went for brunch here, and the stalls in the bathroom even feature Go Card advertisements disguised as postcards, familiar to bar hoppers back in the U.S.

Doshi, who eats a Subway sandwich for lunch, uses a Logitech mouse, drinks Coke, and chooses between Bollywood hits like "Kal Ho Naa Ho" and Hollywood's latest when he goes out to the movies, isn't worried about the West changing the local culture: "The way I see it, it's 5,000 years old. It's not going away," he says.

The programmers who work for him have big aspirations. "I'd like to be the manager in a big company," says Sandeep.

"I'd like to compete with Bill Gates," kids Piyush, drawing approving giggles from his colleagues.

And Deepa and Reena say almost in unison: "Have our own company!" clasping hands.

As for the fears of American workers who look at companies like Webodrome and wonder what they mean for their own job security, Doshi relates a new development: In the early days of Webodrome, 90 percent of their clients were American, but now the firm gets a lot of work from Canada and Europe. In other words, other countries are catching on. "I don't see how they could possibly go about putting in any protectionist measures. It will kill their companies."

Shares