When a friend of mine heard how, in "Man on Fire," Denzel Washington whacks off a guy's fingers one by one and then cauterizes the stumps with a car cigarette lighter (this is before he shoves a plug filled with explosives up another guy's rectum), he said, "So I assume he's not playing the hero, right?" Wrong.

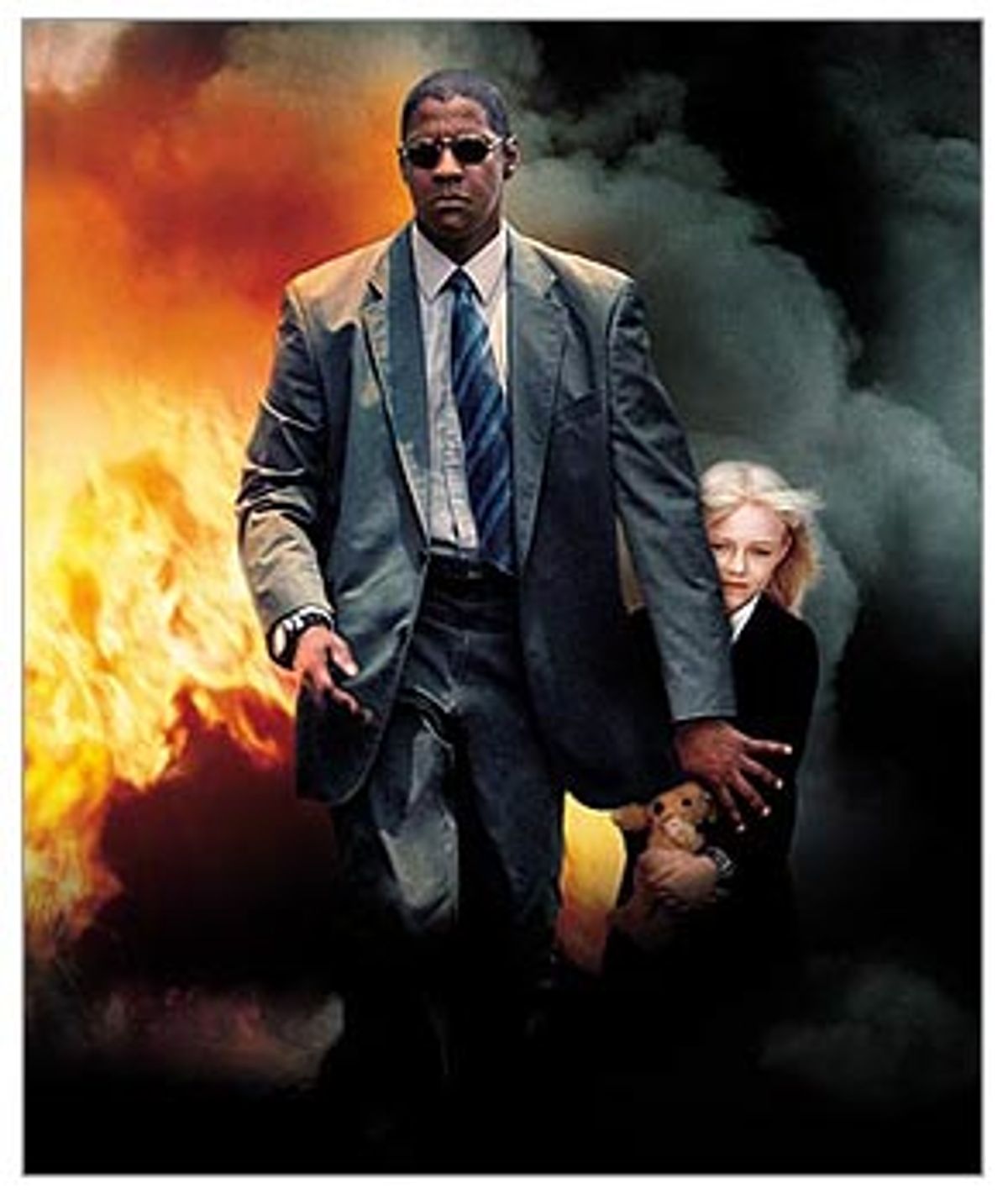

In Tony Scott's "Man on Fire," Washington plays Creasy, a bodyguard with a mysterious, troubled past that the movie never bothers to explain, and he is the hero, out to avenge the kidnapping of Pita (Dakota Fanning), the rich little squirt he's been hired to protect. All that whacking, cauterizing and shoving is happening to the bad guys. Justice is being served, which means that "Man on Fire" is, in Scott's eyes at least, a deeply moral movie.

"Man on Fire" opens with an alarming statistic about the rampancy of kidnapping in Latin America -- in other words, from the get-go it tries to fool us into thinking it's a serious movie. The picture is set, and was filmed, in Mexico City, which Scott and his crazy-legs cinematographer Paul Cameron depict as a seedy hotbed of ruthless crime and corruption.

But worse than that, it's moving around all the time: The streets jiggle, cars and people move in strange, jerky stop-motion, and everyone's faces loom alarmingly close -- Mexico City must be a very rude place, where no one respects anyone else's personal space! Or wait -- could it be the camerawork and editing? Whatever its real-life vices and virtures are, Mexico City is probably not the kind of city you want to piss off, which may explain why, at the end of "Man on Fire," just before the credits roll, the unctuously apologetic missive "A special thanks to Mexico City: A very special place" pops up. Book that honeymoon now!

But what about the rest of "Man on Fire"? This movie isn't just about a kidnapping; it is a kidnapping, and we're the hostages. The first third sets up the special friendship between the booze-sozzled, chronically depressed, suicidal Creasy and his sunny blond charge. She's a friendly tyke, and she asks him lots of questions he doesn't want to answer. When she prods him for the name of his very first girlfriend, he shoots back, a trace of humor showing beneath his rapidly melting protective exterior, "Nunya -- Nunya Business."

That's one of the best lines in "Man on Fire" (its script is by Brian Helgeland, of "Mystic River" fame, who adapted it from a novel by A.J. Quinnell), although that probably has something to do with the way Washington delivers it. His scenes with Fanning, an efficient little actress whose efficiency has been mistaken for talent, are at least relaxed and natural, which is more than you can say about the rest of the movie. Washington is a marvelous actor with slapdash taste when it comes to material: He's so much more enjoyable in pictures like the nicely crafted romantic thriller "Out of Time" (or in "Training Day," where he makes a terrifyingly believable heavy) than he is in this sadistic mess masquerading as a morality tale.

Scott may think he's made a movie about a man who fights (and tortures and kills) for what he believes is right. But he's really all about style, and style only. On the one hand, you want to write off a movie like "Man on Fire" quickly and scamper away as fast as you can: It's just another example of Hollywood excess designed to pack 'em in; maybe it'll be a hit, but it'll be gone soon enough, thank God; and so forth. But there's something particularly vicious and ugly about "Man on Fire," notably the way it sets up all that warm, fuzzy business between the disillusioned bodyguard and the effervescent little girl solely to justify its relentless second act, in which Scott does his damnedest to make vigilantism look like a fine and noble thing.

Scott uses the movie's violence to rev us up -- it serves no other purpose. Instead of shooting his action scenes clearly, so we can see what's going on (not that we'd necessarily want to), he relies on the editing (it's by Christian Wagner) to simulate excitement. "Man on Fire" is a Mexican jumping bean, animated by lots of visual noise including grainy processing, senseless jump cuts and, whenever a character is speaking Spanish, wriggly subtitles in a variety of typefaces, lest we get bored with a good, basic sans-serif. Scott is also damnably fond of the tight close-up. There are so many of them you can hear the actors' pores begging for mercy.

A few supporting performances open up small windows of relief here and there, dissipating some of the movie's noxious gas: Giancarlo Giannini, as a good-guy investigator, has the kind of jaunty, sexy swagger that only gets better with age. And Christopher Walken, as Creasy's wise old pal, nearly brings the house down with his brilliant, knowingly halting reading of the lines "Creasy's art is death. He's about to paint his masterpiece."

Then again, it's dispiriting to see good actors doing smart, solid work with so much unadulterated garbage swirling around them. Scott's art is also death, and we, the audience, are the ones he's jabbing at with his ruthless paintbrush. It's about time someone told him where to stick it.

Shares