As long as the topic is the Christian right, it's easy for those of us on the left to insist on the separation between church and state. But there's at least one example that makes mush of our certainty that religion should never play a role in politics: the civil rights movement. A liberal who argues that religion should always stay out of politics is basically arguing that America could have gone for years without a civil rights act, a voting rights act, a fair housing act: There is no reason to believe any of those gains, nor dozens more, would have happened when they did without the influence and organizational power of the black church.

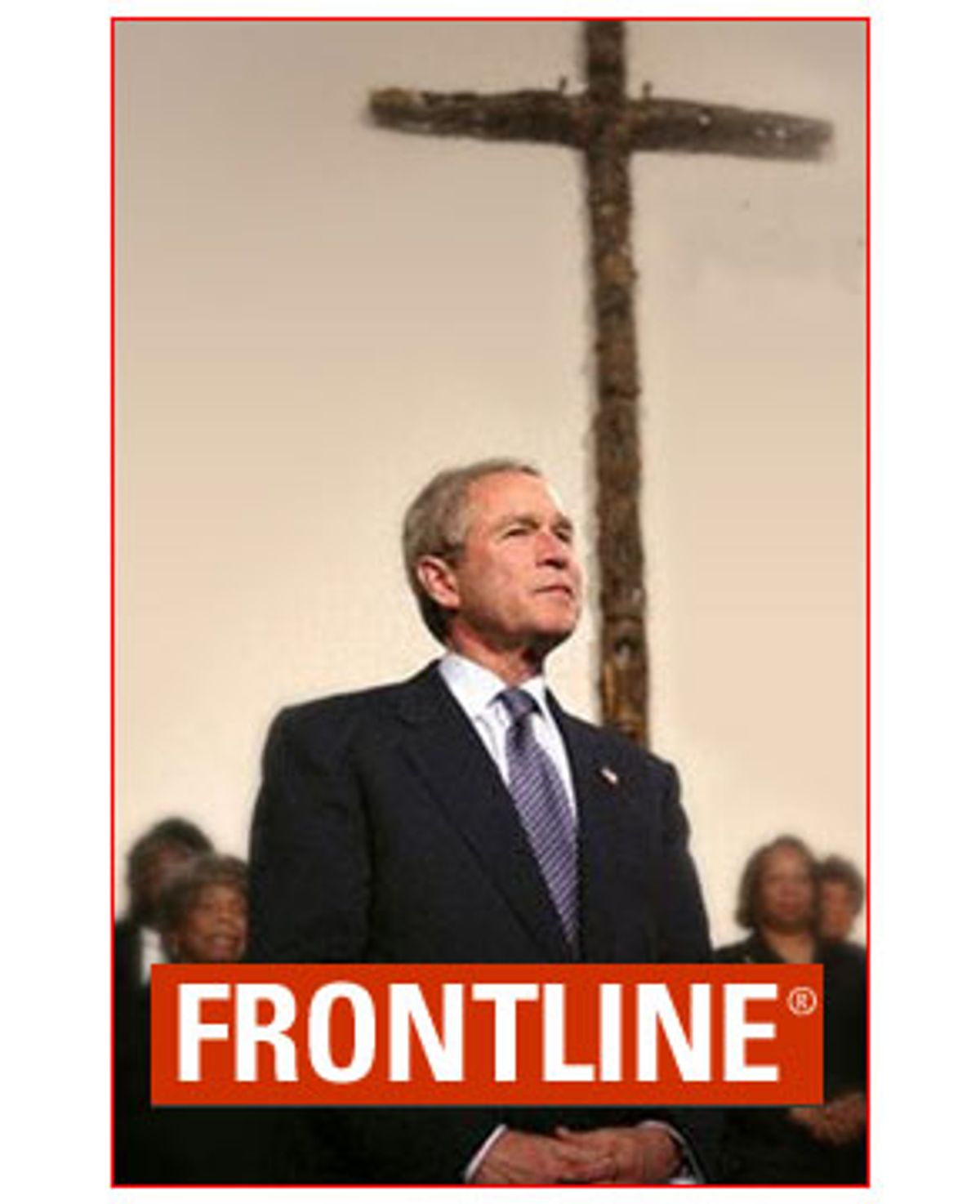

Given that, how does a liberal agnostic who's convinced that more than a fair share of what's wrong with the world has to do with religion watch "The Jesus Factor," the PBS "Frontline" documentary about the part religion plays in the life and politics of George W. Bush? (The "Frontline" Web site says the full program will be available for viewing online starting Saturday, May 1.) For me, the answer is ... uneasily. "The Jesus Factor," which was written, produced and directed by Raney Aronson, makes a compelling case that Bush's born-again Christianity is sincere. Which is not to say that he doesn't know how to use it for political purposes. Doug Wead, who served on George H.W. Bush's 1988 campaign as a liaison to the evangelical community, says at one point in the documentary that Bush's religion is absolutely calculated and absolutely sincere and even Bush himself can't tell which impulse is which.

In the unexciting, earnest and worthy way that's par for the course with "Frontline," "The Jesus Factor" takes the viewer through Bush's conversion. He was raised an Episcopalian and switched to Methodism when he married; by the mid-'80s he was an alcoholic failed businessman and failed congressional candidate on the verge of losing his marriage and his family. A conversation with Bush family friend Billy Graham (which Bush describes here in a typically illiterate Bushism: "One day I spent a weekend with the great Billy Graham") ignited a passion for religion that took hold after Bush joined a men's Bible study group in Midland, Texas. Shortly after, Bush stopped drinking and began to put his life together.

"The Jesus Factor" does an excellent job of explaining the political repercussions of Bush's born-again conversion. With the help of Doug Wead, Bush was able to bring his father's 1988 presidential campaign the support of evangelicals. As Wead notes, the senior Bush's campaign lost the black, Latino, Jewish, even the Catholic vote. This, he says, was "the first modern presidency to win an election, and it was a landslide, and lose the Catholic vote. You could win the White House with nothing but evangelicals if you get 'em all." And remember, this was a victory for a man who had come behind the two Pats, Robertson and Buchanan, in the 1992 Iowa primary.

The mistake that's often made by people who don't like a particular candidate, and certainly made by those who don't like Bush, is to assume that that candidate's positions are cynically convenient instead of sincere. "The Jesus Factor" makes a pretty good case that Bush means what he says. Certainly, you can't imagine a president stupid enough to say, in public, that what's needed in the American judiciary are "commonsense judges who understand that our rights were derived from God" if he didn't really believe it.

At one point, we see Bush criticizing the way the government has traditionally made religious organizations that take federal money change their board of directors to resemble a broader range of the populace. What's absolutely chilling about this moment is that Bush is saying this to an all-black audience. Essentially he's getting them to applaud the same mentality that kept blacks and women and Jews off boards of directors for years. (And we also find out that of the millions handed out to religious groups from the faith-based initiative in the Department of Health and Human Services, none has gone to any Jewish, Muslim or non-Christian group.)

"The Jesus Factor" suggests that "Frontline's" dull, reasoned approach has its virtues. This is one of the few documentaries I've seen that didn't present conservative evangelicals as yahoos and rubes. You can find some or even all of what they have to say appalling, and yet Aronson does them the simple decency of allowing them to present themselves, and the audience the essential courtesy of allowing us to make up our own minds about them. And though I despise George Bush as much as I have despised any White House occupant since Nixon, sometimes his critics make dumb mistakes. Jim Wallis of the liberal evangelical magazine Sojourners is understandably bothered by Bush's "righteous empire" rhetoric. He may be right, as well, that it is theologically unsound for Bush to talk of ridding the world of evil (he quotes the scripture about noticing the sty in your neighbor's eye and not the log in your own). But if Wallis cannot see evil in the planned murder of 3,000 of his fellow citizens, I'm glad Bush can.

But the irony of "The Jesus Factor" is that the man it calls the most openly religious president in recent memory comes across as a man who embodies the separation of church and state for the simple reason that, in him, both institutions cancel each other out. The strongest impression of George W. Bush in "The Jesus Factor" is of a man trying to serve two masters simultaneously and failing to serve either. As someone points out here, you cannot take a pledge to preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States and then make a statement that our rights are derived from God. You cannot, as Wallis notes, misquote lines from the Gospel of John, as Bush did, to make the light of Christ into the light of America. (If John Lennon took guff for saying the Beatles were bigger than Jesus, shouldn't Bush take his lumps for saying America was bigger than Jesus?) But, conversely, you cannot claim to be a Christian and hear, as Bush apparently does, the Gospel's instruction to "succor the poor" as "sucker the poor." You cannot claim to be a Christian and strip away environmental protection from the land that, surely any Christian believes, is God's handiwork.

What's so horrendous about George W. Bush isn't that, despite his assurances to the contrary, his religion informs his policy decisions. It's that Bush embodies the politicians that the political scientist Stephen L. Newman describes in the current issue of Dissent, those who do not understand that it's vital "that the ends of policy be truly public." Newman is arguing against the position taken by the late philosopher John Rawls -- and many liberals -- that the reasons for state action must never invoke religious language. There is nothing wrong, Newman argues, when religious reasons are used to serve a legitimate civil interest. (The civil rights movement is the greatest example; a more unlikely one, the conservative Christian governor of Alabama, Bob Riley, attempting to change the state tax code so that the rich and corporations paid more than the poor because, as Riley said, the other way round was un-Christian.)

But when Bush sponsors a constitutional amendment banning gay marriage, when he opposes stem-cell research (which, as even Nancy Reagan has pointed out, could very well have benefited her husband, a hero to conservative Christians), when in the face of AIDS in Africa or teen pregnancy in America, he ties sex education funding to abstinence programs, he is using private reasoning for ends that may please a portion of the community but do not serve a majority.

At one point in "The Jesus Factor," Wayne Slater of the Dallas Morning News, who has covered Bush for years, points out that the term "compassionate conservative" really means nothing, designed as it is to mean all things to all people, allowing people to hear what they want -- compassion or conservatism. It's a phrase where meaning cancels itself out. The radical notion beneath the measured, reasonable tones of "The Jesus Factor" is that Bush's politics and religion do the same -- they add up to zilch. The horror of that notion is that that emptiness doesn't diminish Bush's ability to spend the next four years throwing the lions to the Christians.

Shares