Studios are so busy grabbing at the bunched-up dollars of teenage moviegoers that they've failed to realize that the most promising market for teen comedies may be grown-ups. No one ever forgets what it's like to be a teenager; it's a subject that's much more satisfying to revisit than to live through. I doubt many adults are flocking to see Lizzie McGuire vehicles of their own accord. But if they were suddenly faced with the modern equivalent of "Fast Times at Ridgemont High" -- or even something as subversively intelligent as "American Pie" -- I suspect they'd fork over their weekly movie allowance in a heartbeat.

Mark Waters' "Mean Girls" doesn't have as much depth or resonance as "Fast Times" or "American Pie." But there's a sly intelligence at work here -- in the writing, the filmmaking and the acting -- that makes it deeply pleasurable to watch. "Saturday Night Live's" Tina Fey, the screenwriter, may have been inspired to write "Mean Girls" after reading Rosalind Wiseman's "Queen Bees and Wannabes: Helping Your Daughter Survive Cliques, Gossip, Boyfriends and Other Realities of Adolescence," but the movie doesn't scan like a grad student's sociology project. (If that's what you're after, check out last year's parentsploitation fest "Thirteen," which suggested, "Reefer Madness"-style, that it's a short road from belly-button piercing to prostitution.)

And yet "Mean Girls," even as it keeps us laughing, treads into some painfully realistic territory, perhaps because the teenage turf it's treading hasn't changed all that much in the past 50 years. There have always been, and probably always will be, social hierarchies in high school. "Mean Girls" reminds us, mischievously, how little those anthill social divisions mean in the grand scheme of adult life, even as it brings back how much "fitting in" matters when you're a teenager.

Lindsay Lohan is Cady, who has been home-schooled for years not because her parents are religious freaks but because they're zoologists (they're played, with generous dollops of good-liberal-parent earnestness, by Anna Gasteyer and Neil Flynn). For the first 15 years of her life, Cady has lived with her parents in Africa, which means that in her case, the notion of high school as intimidating foreign territory isn't just a metaphor -- it's piercingly literal. Friendly, open and trusting, Cady is lost in a place where neither the administrative rules nor the unwritten social ones make any sense. She doesn't realize, for example, that she needs a hall pass to use the bathroom; she has no idea where to sit in the cafeteria at mealtime, which means she eats her lunch crouched in a lavatory stall, alone.

But two fellow misfits, the gentle, lumbering, almost-openly-gay Damien (Daniel Franzese) and tough-but-sensitive Janis Ian (played by Lizzy Caplan -- her character's name is the picture's most obvious acknowledgment that grown-ups are actually the ideal audience for teen movies), quickly take Cady under their wing. Their first act of kindness is to present her with a map of the lunchroom, so she'll know which tables have been staked out by which cliques, among them the Preps, the JV Jocks, the Asian Nerds, the Cool Asians and the Sexually Active Band Geeks (the last of whom are shown pawing, groping and sucking at one another with oblivious abandon).

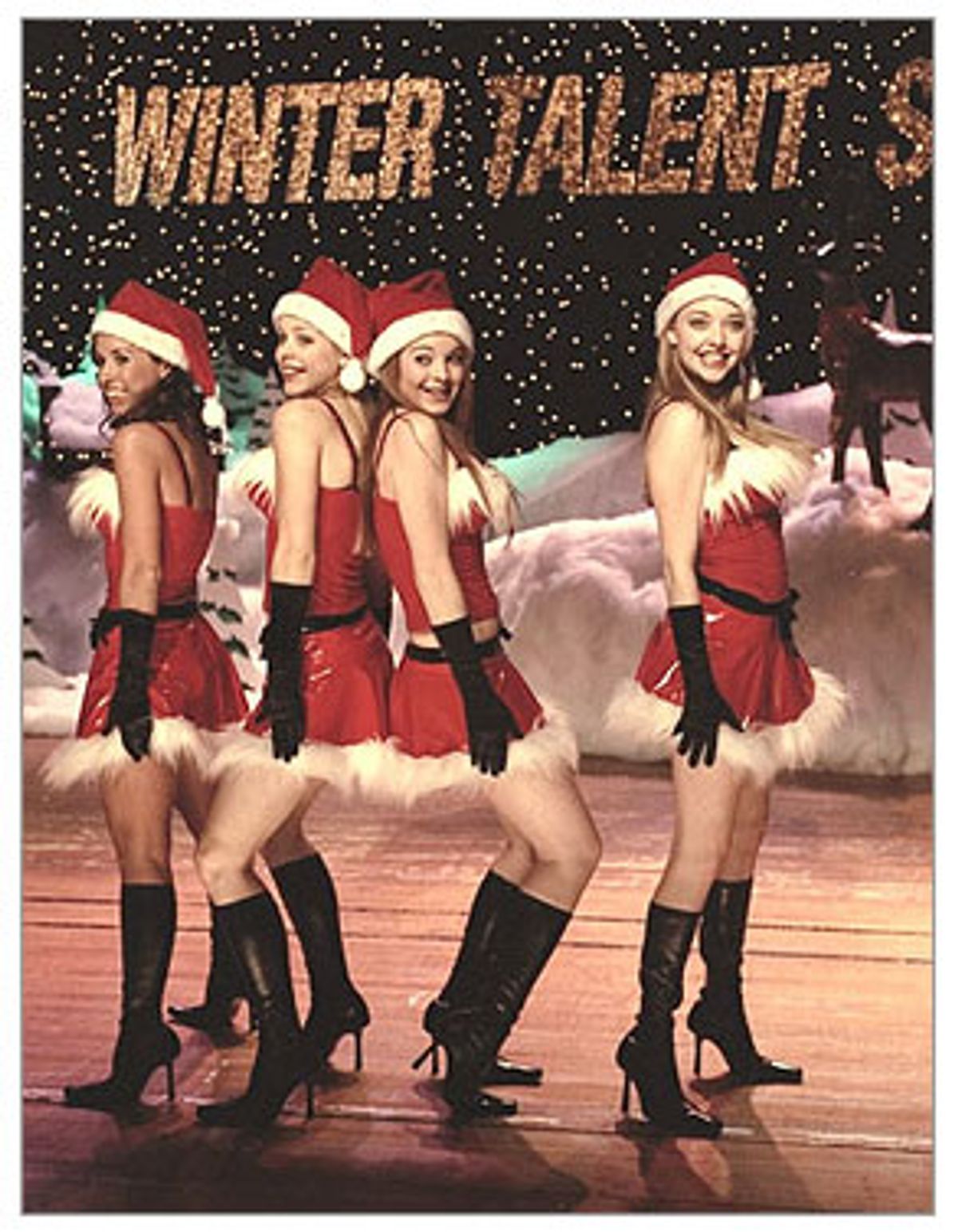

But the most elite table is the one presided over by the school's royalty, also known as the Plastics: Gretchen (Lacey Chabert) is the one who gleans the juiciest gossip about her classmates and wields it like a pink-fur-covered club; Karen (Amanda Seyfried) is the ditzy one who looks adorable and follows the group's rules unquestioningly; and Regina (Rachel McAdams) is the group's (and the school's) Queen Bee, the blond bitch-goddess whom everyone looks up to, emulates and fears.

The Plastics express curiosity about Cady early on, only because she seems like a good target for their cruel scrutiny. (Regina gushingly "admires," with unvarnished disgust, the handmade leather-and-shell bracelet Cady wears.) But Cady amuses and intrigues them, and they decide to initiate her into the fold, but only after they've laid out some very specific rules: On Wednesdays all the Plastics wear pink, and no one must wear a tank top two days in a row. Cady doesn't really want to be a Plastic, but Janis and Damien urge her to infiltrate the group's inner sanctum and report her findings back to them; they hope to sabotage the Plastics by finding out what makes them tick.

That should be simple enough, but then, in high school, nothing is ever simple: Cady falls for the boyfriend Regina has dumped earlier (Jonathan Bennett), not realizing that he's off limits because Regina still considers him her property. Worse yet, Cady drifts all too easily into the rhythm of being a Plastic: The group's power is intoxicating. Worst of all, even though Cady is a good student who's brilliant in math, she dumbs herself down -- refusing, for instance, to join "the Mathletes," an elite group of numbers geeks -- all the better to fit in.

As canny as "Mean Girls" is about the hidden minefields of high-school hierarchies, it's only glancingly homiletic: Cady and her classmates ultimately learn how damaging it is to spread rumors and talk about people behind their backs, but Waters (who directed last year's smart, sprightly "Freaky Friday") and Fey don't deny us the biting pleasure of watching the girls engage in all this nastiness in the first place. "Mean Girls" doesn't turn a blind eye toward the suffering that gossipy girls (or boys) can inflict. But the cruelties inflicted by the Plastics are intelligently stylized: These girls are immediately recognizable as archetypes, which frees us to enjoy the Tilt-a-Whirl of their bad behavior. "Mean Girls" is at its heart a moral movie, even though, for the most part, it keeps a lid on the uppity moralizing. Waters and Fey trust us to grasp the movie's subtexts on our own; they realize that the best way to get the movie's meaning across is to concentrate on keeping the action fleet and funny.

It doesn't hurt that all the actors seem to be having a great time. Lohan pulls off the tricky job of playing the straightforward nice girl without ever seeming stiff or bland. Fey appears as a likably no-nonsense math teacher -- it's a good example of how a performer can shape a small comic role into a character rather than a mere caricature. She's joined by some of her "Saturday Night Live" colleagues, including a few who haven't gotten the exposure they deserve: In addition to Gasteyer, Amy Poehler shows off her trademark comic dementia as Regina's silicone-inflated, valium-addled mom. And Tim Meadows plays a dry-as-dust school principal who's funny precisely because you can't imagine anything ever shocking him.

But the most marvelous performer of all may be Seyfried, as the loopy, innocent Karen. Seyfried (in her movie debut) carries on the proud and unfairly maligned comic tradition of the dumb blond. She acknowledges to Cady that, yes, she may not be all that bright, but she does have her special gifts: She taps her forehead, opens her blinking-doll's eyes wide, and asserts in her wispy voice, "I have a fifth sense!" In case she hasn't made her point, she elaborates: "It's like I have ESPN or something." Seyfried makes playing dumb seem easy, even though it requires an especially meticulous sense of timing: The space between lines is wavier, and it's measured not in beats, or even half-beats, but eighths and sixteenths. Hit the wrong one, and you can make a joke thuddingly obvious. Seyfried gets every note right, riding the dippy waves of her role like an expert surfer.

"Mean Girls" isn't a particularly deep picture, but it does have some weight and ballast: Unlike many contemporary comedies, it doesn't just glide by like a forgettable, overdecorated parade float. It has an appealing prickliness, a quality that intensifies, subtly, both its good humor and its innate sense of right and wrong.

"Mean Girls" may do well with teenagers, but I think grown-ups are its truest audience. Getting through high school is rough for most of us. By the time we've made it through the battle zone, we deserve a lifetime's worth of good movies on the subject. We've earned the right to look back on it all and laugh -- even if that laughter comes with a sting.

Shares