In his 2003 book, "Blinded by the Right: The Conscience of an Ex-Conservative," former self-described "right-wing hit man" David Brock chronicled his flight of disillusionment from the conservative movement. Now, with his new book, "The Republican Noise Machine: Right-Wing Media and How It Corrupts Democracy," about to be published and the launching of his Web-based research and information center, Media Matters for America, Brock sees himself engaged in a 24/7 political war of images and ideas. It's a war, as Brock details in his new book, that conservatives have been waging, often brilliantly and effectively, for more than 30 years.

The right-wing media warfare naturally is most visible during presidential election years. "I've been saying for six months, no matter who was running for office this year, the right has a system in place to caricature that person," says Brock. "This is what I realized after 2000 -- that what happened to the Clintons during the '90s really had very little to do with the Clintons because the same thing happened to Gore in 2000. And then it happened to [Sen. Tom] Daschle when the Senate changed hands in 2001, and it happened to the mourners of [the late Sen.] Paul Wellstone in 2002. It goes on and on." After witnessing how this Republican "noise machine" again worked so well in shaping the caustic and undermining press coverage of Al Gore's presidential campaign in 2000, Brock is trying to awaken the public from slumber about these techniques.

Media Matters is a "not-for-profit progressive ... center dedicated to comprehensively monitoring, analyzing, and correcting conservative misinformation in the U.S. media." In its first few days of operation, the site caught conservative columnist and Fox News contributor Linda Chavez calling John Kerry "a communist apologist" and then denying it when she was asked about the accusation on television. (Pressed on Al Franken's Air America radio show days later, Chavez conceded she "misspoke.")

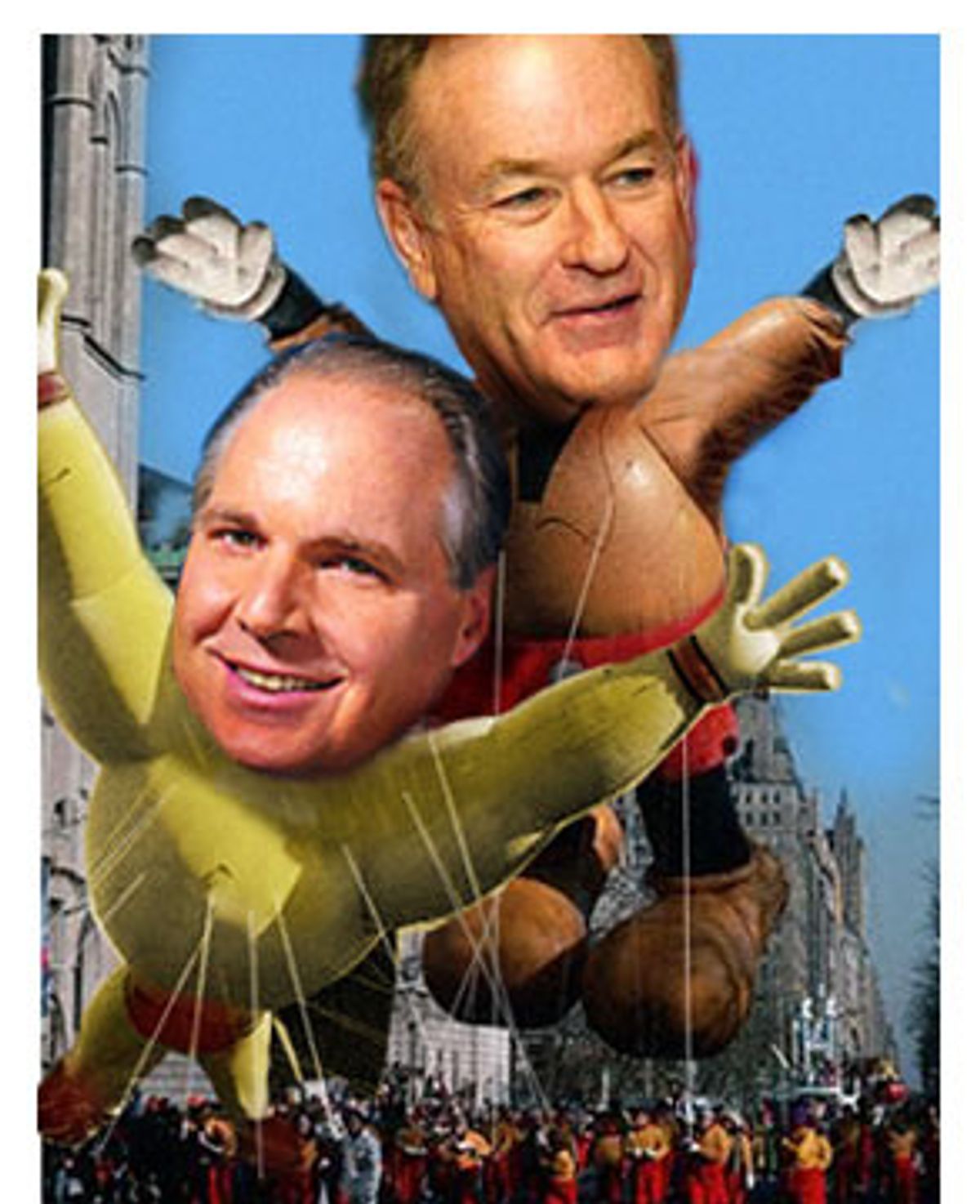

Catching Rush Limbaugh or contributors to Fox News spreading misinformation may sound like "shooting fish in a barrel," but Brock says the right-wing noise machine's effect on the mainstream press poses a large danger to rational debate and coverage of issues. Too often, he says, what the right concocts ends up -- often within hours -- percolating in mainstream press outlets, which, rather than debunk the Republican spin, uncritically adopt it as their own. "If the mainstream media were doing their job, Media Matters would not have to exist," Brock told Salon.

At what point did you decide you wanted do something beyond the book, like the Media Matters Web site?

Shortly after publishing "Blinded by the Right," I got involved in conversations with a lot of different progressive leaders, and there was an ongoing conversation about what responses to the right might be fashioned in terms of building institutions. I really believe that a permanent response is required that goes beyond campaigns -- that a communications infrastructure needed to be built. I met with people and tried to educate them about my experience and the two basic things I learned.

And what are those?

One is communications and the other is strategic philanthropy, which is how the right wing funds all of its enterprises.

So then I started working on "The Republican Noise Machine" in the fall of 2002, and a few things occurred to me. I had done extensive research on the conservative organizations that police and monitor the media, tracing back to the establishment of Accuracy in Media in 1969. I concluded that monitoring was a foundation piece of the entire conservative communications apparatus. Those groups had monopolized the conversation about the media so that all one ever hears is "liberal bias, liberal bias, liberal bias." There hadn't really been an institution with research capacity to engage that issue from the left. I certainly read Eric Alterman's book ["What Liberal Media?"] and Al Franken's book ["Lies and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them"], and I realized there was an active conversation going on and maybe the time was right.

You were able to raise $2 million for Media Matters. Was that easier than you thought or harder than you thought? What was the environment when you were looking for backers?

It was very receptive -- partly, I think, because there are other institutions being created and people have begun to understand that what the conservatives call the war of ideas doesn't go away after an election is won or lost. That's a critical thing in terms of donor awareness. Again, because of the education others were doing, people were beginning to understand at least what had happened to Gore in 2000.

With your book and with Media Matters, the Center for American Progress and the Air America radio network getting started, is the good news that the progressive media infrastructure is being laid in place, and the bad news that that puts the left where the right was in about 1972 in terms of trying to shape the media debate?

Not exactly, because information moves much, much faster today. Reed Irvine [at Accuracy in Media] used to write letters to the editor, and when they weren't published he would take out little ads. Today, there's a much more sophisticated system in place, so that you can, with proper funding and good research, drive the message much more quickly. But it's true that progressives are behind the curve. In addition, I come out of a conservative culture where there's a lot of patient capital. [Members of the right] invested in the idea of school vouchers for, like, 19 years before they got any political traction on it. So, yes, it is the beginning, but it might not take $1 billion, which [is how much] the right has spent on just 50 think tanks. It's going to take some strategic philanthropy, and it's going to take attention to sustainability.

You mention the proliferation of conservative think tanks. Why did the left mostly ignore the think tank game?

One aspect is that the conservative organizations were themselves organized in response to what they saw as threats from various liberal movements, like the consumer movement and the women's movement. But all those liberal movements were organized as single issue; there really wasn't an effort to bring them together into a broader ideological stance in the way the right has done. What John Podesta is doing [at the Center for American Progress] is a broad-based and multi-issue organization. There are very few of those. Conservative organizations like the Heritage Foundation (I worked at Heritage) have very slick marketing savvy, with a high amount of their budgets going to promotion and public relations. I imagine there's an intellectual resistance to doing that [on the left] on the basis of its being gimmickry, or too slick: If our ideas are good, why do we have to sell them?

You write about the conservative cradle-to-grave jobs network that goes along with the think tanks, opinion journals, magazines, radio shows and syndicated columns, and book deals and speaking fees. It sounds pretty cushy.

It is. There's every financial incentive in the world to stay in the conservative movement forever. That [network] allows the conservatives the freedom and the confidence to devote their attention to influencing the mainstream without actually becoming a part of it. It also means that when young people are trained they can stay -- it's not an up-or-out situation. You have very senior people editing magazines who can have families. And, again, it's sustained support. Editors of conservative magazines aren't out trying to raise money. The money is there; the cash reserves are in the bank.

You write in the book about the Nixon administration and Spiro Agnew's famous 1969 speech attacking the elitist press corps. You say: "It would take years of work by the Republican right to undermine and subvert journalism by painting it, essentially, as an un-American force." How long did it actually take, in your opinion? When did the right effectively accomplish that?

Well, let me use personal landmarks. In 1986 I was working at a sister publication of the Washington Times, Insight magazine, and I then became an editorial writer at the Washington Times. And I don't think it had happened during that period because the paper had the same circulation it has today, about 100,000 readers, and it was considered to be a suspect, unreliable right-wing publication. It had, from the inside, very little impact in getting its message off the page; its stories didn't really go anywhere. But then a few things happened: Limbaugh went to national syndication in '88, and then you had the proliferation of cable, and then you had the Internet. So today, 16 years later, someone writes something in the Washington Times that may be unreliable, but it resonates because Limbaugh could read it on the air, or [Matt] Drudge could post it, or the author could go on Bill O'Reilly's show. So it's a completely different climate. During the '90s the flow of misinformation was established.

What's your take on how the press has covered President Bush?

There's no question in my mind that a similar record with a different president would have resulted in different media treatment.

How do you think the press has treated John Kerry over the past few months?

Clearly there's already some evidence of a phenomenon I describe in the book of the ability of the right-wing media to project a caricature. For instance, [Media Matters noted] that Drudge wrote an item about a hairstylist being flown in for Kerry before his appearance on "Meet the Press." There was no sourcing, so one didn't know what to make of it. Then I believe the [next step in the] chain was that Jay Leno mentioned it in a joke, which is fine. Then the AP and Reuters reported the Leno joke. Then Linda Vester on Fox the next day claimed that Fox News had independently confirmed the story, but her story didn't provide any sourcing, so we didn't know what to make of that. And then [Fox anchor] Brit Hume asserted the same thing later in the day.

So this is the kind of problem we are already seeing for Kerry -- that's the climate a candidate has to live in. The right can distort anything it wants. The playing field is so unlevel; there's a systematic disadvantage.

Meanwhile, the Wall street Journal last Thursday had a Page 1 piece on its latest polling, and not until the 14th paragraph on the jump page did it report that Bush's approval rating had "slipped to 47%, the lowest of his presidency ... By a 50%-to-33% margin, voters say the nation is headed in the wrong direction." The press seems to be almost embarrassed -- or thinks it's impolite -- to report that Bush may be in serious trouble or that he often tells lies. How does the Republican noise machine fit into that dynamic?

The Republican noise machine has an echo effect. It sets a climate and helps set parameters and helps form impressions -- and because there is so much noise coming out, there's no way that doesn't seep in. The absence of a liberal noise machine pushing back in an accurate way has to have some effect in there somewhere.

Here's another important point. Every day, there actually are important stories that appear in places like the New York Times and the Washington Post, but they don't leave the page. Someone living in Dallas who reads the Dallas Morning News and is stuck in their car with very little choice on the radio, and then goes home and watches cable, never learns about some of the really good reporting that exists. So when [there is] something accurate that would be quite damaging to the administration, how do you get people to hear that? How does it enter their consciousness when there's no echo and now way to actually deliver [the information]? That's a huge problem.

You mentioned the Gore campaign coverage, which now has become almost a case study in bias and how the mainstream press essentially adopted the Republican National Committee's talking points. Looking back, it's amazing to note the deafening silence with which that phenomenon was greeted even by the so-called liberal mainstream press. People who knew what was going on -- columnists and so forth -- sat on their hands and did nothing. Why do you think so many progressive columnists and media people didn't do anything then?

I'm not quite sure. I'm an expert in the conservative media. I've never worked at the New York Times, so it's hard for me to say, and I don't like to attribute motive.

Well, do you think this could ever happen again on that scale, that the right would be able to dictate campaign coverage to the mainstream media? Or is the hope with the new infrastructure to be able to make a fuss when misinformation starts to flow?

The hope is to do that. And part of it is providing the factual information in a reasonably quick time -- and through the creation of institutions to give [the media] some backbone so people don't feel out on a limb by themselves.

Do you think Gore felt that way during the 2000 campaign, wondering when people in the press were going to come forward and correct the media misinformation? I got the sense the campaign didn't want to start arguing about newspaper columns because it would seem petty.

Right. And perhaps there was not an understanding of what was happening, or people just kind of laughed it off.

One significant problem is that people [on the left] are in denial about the impact of conservatives in the press. They dismiss something as one story and don't think it will snowball. Liberals don't think these people matter; they think they're crackpots. They may well be crackpots, but they matter. There may be a slow learning curve about understanding that.

Are folks on the left sadly mistaken if they think the Al Hunts and the Margaret Carlsons of the D.C. press corps are going to stand up to the noise machine? As you mention in your book, they don't see that as their job.

I think there's just more genuine independence among columnists and pundits who might be considered liberal. But then there is also that more moderate establishment that doesn't see its job as defending the Democratic Party -- which is not meant to be critical of the people who don't want to engage in that fight. But who else will do it?

Those moderates are certainly presented on the "Crossfire"-type shows as the counterbalance to the Republican noise machine.

I've been carrying around this ad from a few months ago for the MSNBC lineup for what I believe was a debate night. It had Chris Matthews in the middle and then Norah O'Donnell, an MSNBC journalist, and then Keith Olbermann, who is a neutral MSNBC host, and then [former Republican speechwriter] Peggy Noonan and [former Republican speechwriter] Pat Buchanan and [former Republican congressman] Joe Scarborough. What is that? Forget about pundits who write columns that may be moderate to liberal. The worst of it is that TV producers position journalists and reporters against these right-wingers. Not only is it not a fair fight -- because the journalist isn't going to engage in a partisan debate -- but it reinforces the notion that the press is advocating a liberal agenda. It happens all across cable television.

Shares