The opening scenes of André Téchiné's "Strayed" operate with an almost brutal efficiency. The film begins in June 1940 with the retreat from Paris ahead of the Nazi advance. We see country roads clogged with people and autos and carts, all of them loaded down with possessions. It's not that different from what other dramatizations have shown us. But how Téchiné, his editor Martine Giordano and cinematographer Agnès Godard have chosen to show it to us is different.

Téchiné and Godard favor tight, close shots instead of sweeping ones. The advance of the Nazis didn't leave much time to stop and admire the view, so we're spared the usual panoramas of the lovely French countryside. Instead, we get a feel for what it's like to sit in an immobile car while an unending stream of people passes by the window, and for how open and unprotected this landscape is when German planes strafe refugees. As the wave of bullets advances, Godard's camera moves along a row of refugees as, one by one, they fall limply aside. When the planes return to drop bombs, we watch from ground level as the characters do. The planes seem close to touching the earth, and the bombs come down from just a few feet over our heads. Everything happens rapidly but with perfect clarity.

This no-nonsense, one-thing-after-another approach lifts the retreat from Paris out of the realm of historical myth, keeps it from becoming another period-film pageant and gives it the hard specificity of fact. We understand that events like the ones we're watching actually occurred, that people were murdered and that others barely escaped.

The immediacy of these scenes hooks you, obliterating the distance we often feel watching historical recreations. And then, as in almost every André Téchiné movie I've ever seen, an off-putting distance starts to take over.

Téchiné may be the most technically gifted of all contemporary French filmmakers. He works with a precision and a rigor that makes you feel everything he's showing us has been carefully selected and calibrated to contain an exact meaning. But with the exception of his 1994 "My Favorite Season," I'll be damned if I can figure out what those meanings are. Even when I've loved watching Téchiné 's movies, as I did the 1986 "Scene of the Crime," I've been perplexed by them. When a director shows the confidence that Téchiné does, you're apt to think you're dim if his movies leave you uncertain as to what the director wants you to feel. But as sophisticated as Téchiné's filmmaking is, his ability to sustain cohesive emotion and meaning over the course of a movie -- and to transmit those emotions and meanings to an audience -- feels cocooned. On some basic level, his meanings remain private ones, hanging just out of our reach.

"Strayed," adapted by Téchiné and Gilles Taurand from Gilles Perrault's novel "Le garçon aux yeux gris" ("The Boy With Grey Eyes"), tells the story of four people caught up in the retreat from Paris. Odile (Emmanuelle Béart), a widowed schoolteacher in her late 30s, survives a German bombing raid along with her teenage son, Philippe (Grégoire Leprince-Ringuet), and her young daughter, Cathy (Clémence Meyer). Their lives are saved thanks to Yvan (Gaspard Ulliel), a 17-year-old country boy who finds shelter for them in a large, comfortable house from which the owners have fled.

Odile at first balks at invading someone else's house. But with the surrounding villages evacuated and the German military police posting warnings that looters will be shot, and having lost all her own possessions, the house offers the only chance of providing shelter for her family. Yvan, who goes out daily to scavenge for fish and rabbits, keeps the family from going hungry.

"Strayed" is about how convictions that seem unassailable fall away in a time of war. Odile's strength has always come from the way she has managed the certainties of life. But the war obliterates everything she thought she knew, and she finds herself dependent on Yvan's cunning and survival instinct. His hunting isn't confined to rabbits and fish. At night he goes out scavenging the corpses of the war dead. Of course, it appalls Odile, and she balks when she sees her son starting to hero-worship him. But he represents the ugly reality of a war she is trying to hold at bay.

That's not at all a bad setup for a drama about how war transforms and deranges everyday life. The trouble is that it feels too elemental for the nuances and ambiguities Téchiné's method suggests. He doesn't have the purity or the intensity that would have made the story perfect for a great humanist filmmaker. You can imagine what Jean Renoir or Vittorio De Sica (or the Quebecois director Claude Jutra) would have done with this material. Téchiné roots around for psychological and moral complexity and in the process he defuses the emotional impact that a simpler telling of the tale would have.

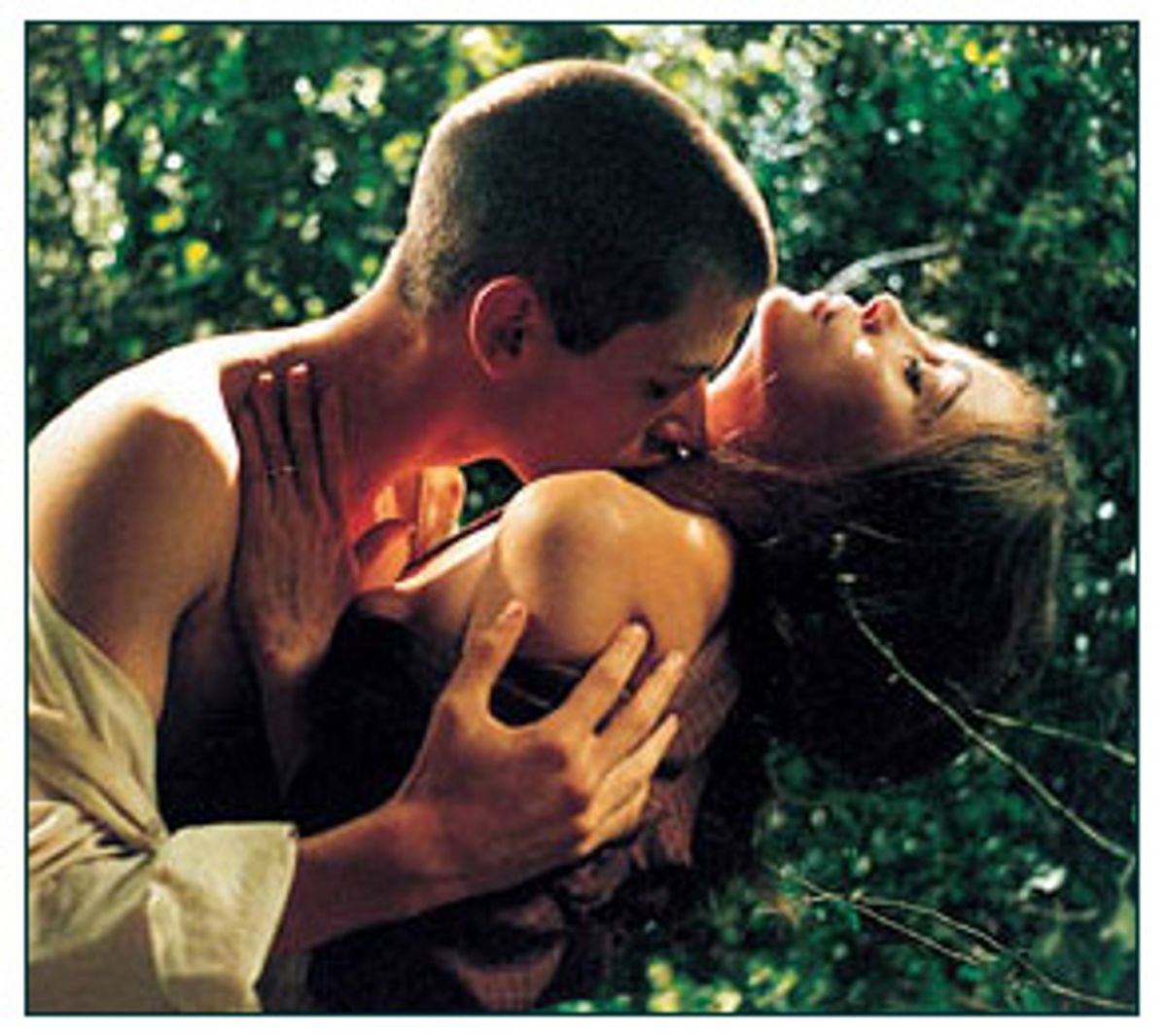

This is not an argument for simplemindedness over complexity. As intelligent as Téchiné is, something about his method feels worked-up here, not quite believable. Next to the French peasant boy played by the late nonactor Pierre Blaise in Louis Malle's 1974 "Lacombe, Lucien," the role of Yvan feels like a conceit, less a character than an embodiment of Man as Animal. And Emmanuelle Béart may be the perfect Téchiné actress, though this is less a compliment than it sounds. She's fitting here because her performance is both obvious and remote. There isn't a moment when she doesn't feel fully immersed in Odile, and yet that immersion results in a closed book. The meanings she finds, like the meanings Téchiné finds, feel private, not fully communicated. When Odile and Yvan's relationship takes a turn to the sexual, it seems contrived instead of having evolved out of what has passed between the two actors. Neither Béart or Ulliel have transmitted the hunger to make the scene work.

It's hard to know how to evaluate "Strayed" (which is dedicated to the memory of the novelist Monique Wittig). It's an impressive, intelligent, compact piece of filmmaking. (Not the least of its virtues is the cinematography of Agnès Godard, who continues to astonish. Her work here is more stately, more planned, than the exploratory character of the work she has done for Erick Zonca in "The Dreamlife of Angels" and for Claire Denis in "Beau Travail." But it escapes the static quality that can turn period movies into a catalog of production values. It's beautiful without being "pictorial.") But Téchiné might be one of those directors whose work is best appreciated by critics and other filmmakers. It's very hard to say to the general public that you should see "Strayed" because the technical rigor of Téchiné's work is so exciting -- though it is. Téchiné is sophisticated, but it's a lopsided sophistication. You can only hope that the emotional breakthrough that seemed promised by "My Favorite Year" will, one day, be sustained enough to equal his technical accomplishment.

Shares