In an early scene from a new documentary about his life, Billy Joe Shaver is dressed head-to-toe in denim and standing on the linoleum of his kitchen floor. He looks, as he always does, like he just came in off the ranch, and he takes a slug from a plastic gallon jug of water that he pulled from the refrigerator. "I usually just drink from this," he says to the camera. "Ain't nobody else here."

Shaver, the original country music outlaw, is alluding to the fact that his mother, wife and only son have recently died, leaving him, at age 64, almost entirely alone. The film, "The Portrait of Billy Joe," debuted in March at the South by Southwest Film Festival in Austin, Texas, where Shaver's reputation as a songwriter preceded him -- as did his Job-like biography of trials and tribulations. That the film, currently making the festival rounds across the country and overseas, was produced by Robert Duvall and directed by Duvall's girlfriend, Luciana Pedraza, added to the buzz around the sold-out screening.

The 57-minute film is affecting and surprisingly funny, largely because Pedraza chose her subject well. She allows Shaver to tell his story in long, self-effacing monologues without cuts to interviews of famous friends or music critics. Where the film occasionally falls short in providing context for Shaver's life and career, it compensates with remarkable intimacy.

Shaver admits in the film that his dreams of stardom died years ago, but the documentary is part of a growing recognition that Shaver has been overlooked for too long. In the liner notes to his posthumous box set, Johnny Cash writes that Shaver was his favorite songwriter, while Willie Nelson claims in a blurb accompanying the documentary that Shaver "may be the best songwriter alive today." The love-fest transcends generations: Longtime fan Kid Rock recently volunteered to produce Shaver's next album.

Still, you may be forgiven for wondering: Who the hell is Billy Joe Shaver?

I've spent a lifetime, making up my mind to be

More than the measure of what I thought others could see

Good luck and fast bucks are too far and too few between

There's Cadillac buyers and old five and dimers like me

-- From "Old Five and Dimers Like Me," 1973

Shaver lives in a tattered two-bedroom house outside of Waco, Texas, with a rusted wheelbarrow in the yard and a handwritten sign taped to the front door that reads: "Do Not Disturb: I Have Not Slept in Two Days." He wrote that sign three years ago after his only son and lead guitarist, Eddy, died of a heroin overdose, and every late-night honky-tonker in Central Texas felt the need to stop by and pay his condolences. He's kept it there ever since.

The house, a low-slung brick structure with a creaky front-porch swing, sits about 20 yards from Interstate 35 on the south side of town. Known these days as the breeding ground for apocalyptic cults and homicidal basketball players, Waco is actually a city of 100,000 or so working-class folks, where Sunday-morning piety is matched by reckless carousing in beer joints on Friday and Saturday nights. Shaver is not famous here: He says his neighbors don't even know that he is a musician -- or, if they do, they don't care to talk about it much.

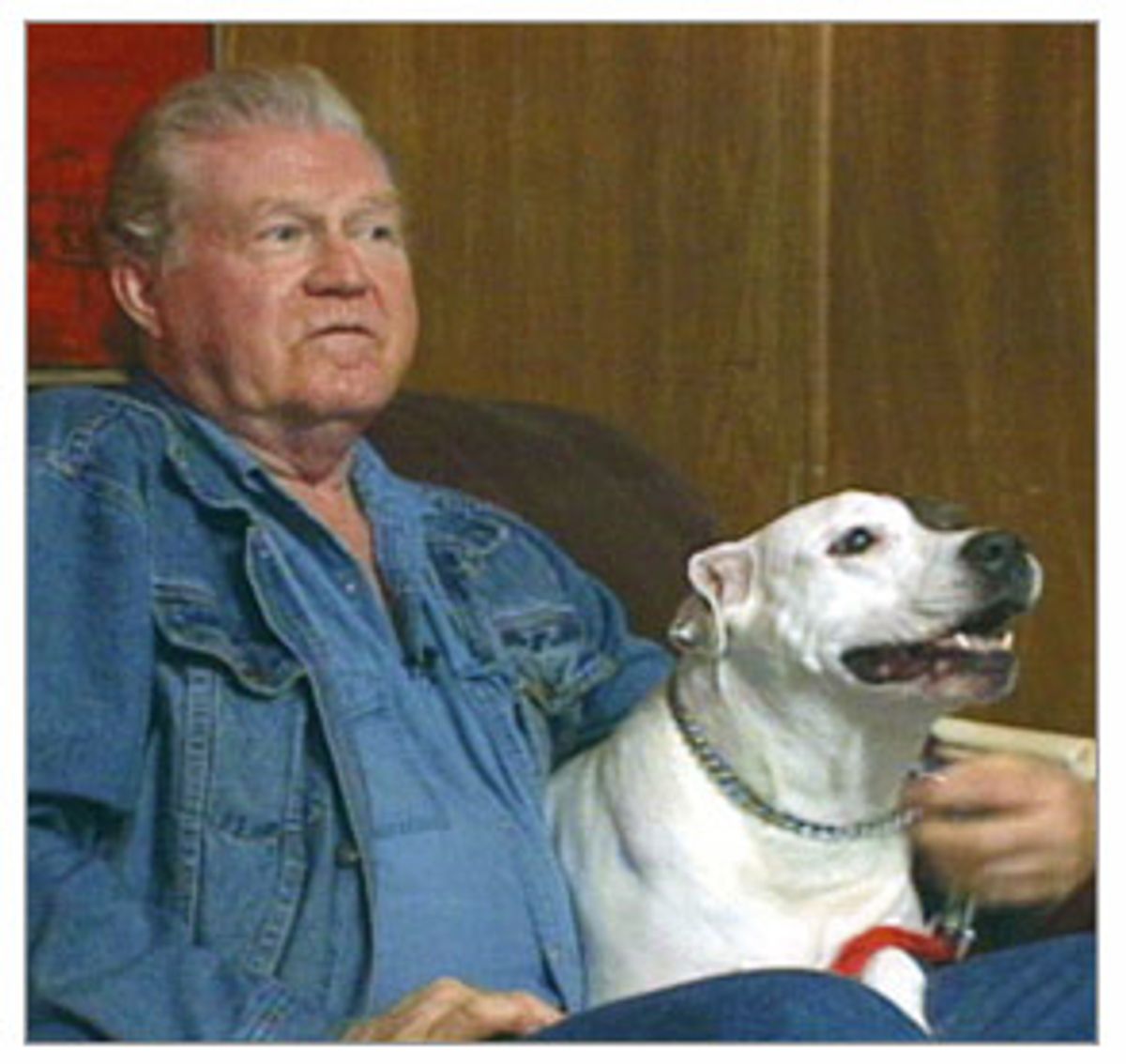

Shaver greets me at the front door with an explanation about the sign and a warning to avoid sudden movements around his two pit bulls. It's clear from the disarray in the living room that the dogs have been using the sofa and recliner as chew toys, and blood droplets on the floor mark the site of a recent tussle. To discourage this behavior, he reads to them from the Bible. "They say if you read the Bible out loud, it'll scare off all the bad spirits," he says, a grin spreading across his broad face as he rubs Shade, the younger and meaner of the two. "My dogs, they got some bad spirits in 'em."

Shaver's face, carved by years in sun-drenched fields and smoky bars, is drawn and tired -- he's been battling pneumonia -- but he laughs easily and often until the subject turns to his family. In 1999, the same year he lost his son, his wife and mother died of cancer. He stands before the mantel that holds their pictures and acknowledges that he has not yet recovered from the terrible trifecta of that year. He spends most holidays, including last Christmas, alone at home with his dogs.

"I'm lonesome, yeah," he says. "I don't do much of nothing around here really. I don't fish or hunt or anything anymore. I just write songs."

There are thousands of them, jotted down on notepads or sung into a microcassette and stuffed into a box in the back room. He's been writing since he was 8, and he'd be doing it even if the dogs were the sum total of his audience. The process is cathartic, as if by documenting his traumas they will somehow start to make sense. Dozens of artists, including Elvis, Johnny Cash and the Allman Brothers, have covered his songs even though they are unabashedly autobiographical. The lyrics, like the man, are entirely unvarnished. After a concert not long ago, a man approached Shaver and told him that he was John Steinbeck's son and that Steinbeck was a big fan. In retrospect, it seems unlikely -- Steinbeck died before Shaver released his first album -- but not inconceivable. Both writers share an affection for the dispossessed and forgotten, even if Shaver's temperament is significantly more rowdy.

In 1973, Waylon Jennings used nine Shaver songs to create "Honky Tonk Heroes," the seminal album that Country Music Television recently ranked as the second-best country album of all time. But Shaver's influence stems as much from his attitude as his music. "Without Billy Joe, there wouldn't have been a Waylon, at least not a Waylon as an outlaw," says Kinky Friedman, an acclaimed songwriter before he became a best-selling mystery novelist. He says Shaver "was the Che Guevara and Waylon was the Fidel Castro who got all the money and the power."

Indeed, thanks to a succession of bad contracts, bad choices and bad luck, Shaver is far from financially secure.

"I don't know what [record companies] do with that money, I really don't," he says. "Don't much care, really. Songs mean more to me than money. If I heard one of my songs on the radio and I didn't write it, I'd have a fit. I'd give everything I own just to have written that song. They're little time capsules, and when I sing 'em I almost feel like I'm there."

Taken together, those time capsules form an outline of his life: the hardscrabble childhood, the hard-living honky-tonking and the drama of recent years. It's all there -- sometimes explicitly, sometimes obscured in the verse. But when he tells his story over hamburgers and tater tots at a nearby greasy spoon, he goes even further back: "My father actually tried to kill me when I was inside my mother."

Put snow on the mountain, raised hell on the hill

Locked horns with the Devil himself

Been a rodeo bum, a son of a gun

And a hobo, with stars in my crown

-- From "Ride Me Down Easy," 1982

Shaver's father, Buddy Shaver, was a violent bootlegger who beat his wife and left her for dead in a backwoods pond. He thought she was running around on him even though she was seven months pregnant with Billy Joe at the time. She recovered from the beating, but refused to raise that man's son and left soon after Billy Joe was born. He was raised by his grandmother in Corsicana, Texas, a small town of about 20,000 about an hour southeast of Dallas.

As soon as he could understand, his grandmother steeled him to the reality of their situation: There is no Santa Claus, she told him, nor anyone else who is going to give you something for nothing. She would walk him down to the general store where the proprietor, with a wink, promised to give them groceries on credit if the boy would sing a few songs. And he would, standing on a cracker barrel believing he was literally singing for his supper.

His grandmother died when he was 12 and his mother, by then a honky-tonk waitress in Waco with a new husband, reluctantly took him back. As he grew into a man, he displayed a wild streak that would make his father proud. He dropped out of school after eighth grade, hitchhiked around the country working odd jobs, and eventually joined the Navy. Not surprisingly, his stint in the military was short-lived: He was kicked out for punching an off-duty officer, so he went back to Waco.

At 21, he met Brenda Tindell, who was 17 and pregnant when they married later that year. She was as headstrong as he was, if not more, and they made a rambunctious pair. Eventually, they would divorce twice, marry two more times, and break up and get back together more times than they could count.

Brenda's family owned a ranch, so Shaver worked there breaking horses, but also worked in a sawmill to support his young family. He played guitar and wrote, but a music career was nothing more than a distant dream. He was building a book of songs that he thought were better than what he heard on the radio but, by his mid-20s, he had yet to perform a single one of them in front of an audience. He spent most of his time in bars fighting with men who took a second glance at Brenda, and there were plenty of them.

Then, in 1966, at age 27, he mangled his right hand when it got caught under a blade at the sawmill. He drove himself to the doctor, where they took parts of three fingers and barely saved his arm. Shaver got divorced for the first time shortly thereafter, in part because Brenda thought he was an idiot for cutting his fingers off and in part because she thought his fantasy of becoming a big-time songwriter was one of the most ridiculous things she'd ever heard. He hopped a cantaloupe truck headed to Nashville, Tenn., and set out to prove her wrong.

The devil made me do it the first time

The second time I done it on my own

-- From "Black Rose," 1973

The late 1960s and early 1970s were the heyday of the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville. The music was heavily produced and overtly commercial, saccharine pop far removed from country music's origins in the blue-collar confessionals of Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Williams. Male singers wore sequined suits and kept their hair short, and their songs were thematically and politically conservative. A few iconoclasts, like Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson, chafed at the system but generally met with stiff resistance from label execs.

Shaver fared even worse. For his first several years in Nashville, he slept in his truck and washed dishes to make ends meet. Eventually he opted to make an impression with Harlan Howard, a prolific songwriter who wrote Patsy Cline's "I Fall to Pieces" and had 15 songs in the top 40 in 1961 alone. In 1968, Shaver drove a motorcycle onto Howard's front porch and announced, "My name's Billy Joe Shaver and I'm the greatest songwriter in the world!" Howard replied, "Hell, I thought I was," but after a quick listen, he sent Shaver over to Bobby Bare with a recommendation. Bare was an established songwriter and performer who collaborated with Shel Silverstein, among others, and had a reputation for appreciating unconventional talents. He gave Shaver a job writing songs for $50 per week.

For three more years, Shaver scraped to get by, living out of his truck and gobbling amphetamines so he could stay up all night writing. When he ran out of money, he'd drive back to Texas to work construction for a while and then head right back to Nashville when his pockets were full. He got several songs recorded -- Kristofferson put Shaver's "Good Christian Soldier" on his first album -- but after more than five years he was still looking for the proverbial big break.

It came in 1972, when Waylon Jennings overheard Shaver playing some songs in a trailer before a concert in Dripping Springs, Texas. (The show featured a mix of country, rock and folk performers in a field outside of Austin -- two years later, Willie Nelson adopted the concept as his annual Fourth of July picnic.) Impressed by what he heard, Jennings agreed on the spot to record a collection of Shaver's songs about restless cowboys and no-account boozers. But Jennings got wrapped up in other projects and, after six months of waiting, Shaver was desperate. He tracked Jennings to a Nashville studio, where he was partying with an assortment of groupies and bikers and ostensibly recording an album.

When Jennings heard Shaver was waiting, he sent a messenger out with a $100 bill. The message was clear: Take the money, small-timer, and quit bugging me. Shaver sent a message back: Shove your $100 up your ass.

When Jennings emerged from the booth accompanied by two bikers, Shaver pounced. "Waylon," he yelled, "I don't care if you do an album of my songs or not but you're going to listen to them now or I'm going to whip your ass in front of everybody."

The bikers started toward Shaver, relishing the idea of tearing this hayseed to shreds, before Jennings talked them down. He hustled Shaver into a nearby room, and said, "Hoss, don't ever do something like that again. You could've gotten killed."

Shaver pulled out his guitar and played three songs. Jennings was hooked. Over the objections of the RCA brass, he made those songs the centerpiece of his next album. The record was called "Honky Tonk Heroes," after the title of one of Shaver's songs. Of the 10 tracks on the album, Shaver wrote nine. Eventually selling more than 5 million copies, it became the touchstone of the Outlaw movement, which infused country music with a rock 'n' roll attitude and provided the blueprint for a series of performers to follow, including Jerry Jeff Walker, David Allan Coe and Hank Williams Jr. (The movement's next great record, Willie Nelson's "Red Headed Stranger," came out two years later.)

It also made Shaver a commodity. He reconciled with Brenda, who came to Nashville with their son, Eddy. Shaver recorded three solo albums in the 1970s, all of them critically acclaimed but commercially disappointing. It didn't help that he was with a different record company for each record, and each went out of business within a year of the record's release. Still, he was a sought-after performer and fans would stuff $100 bills in his shirt just for showing up at a club. Now that he could afford to, he spent most of his time drinking, snorting and brawling his way around Nashville, reinforcing his reputation as the wildest of the Texas outlaws.

"It was like the Old West," Shaver says. "It seemed like there was always somebody coming to town looking to prove they were tougher than me."

Other songwriters revered him, and worried about him. Tom T. Hall voiced his concern with a song, "Joe, Don't Let Your Music Kill You," and Kristofferson weighed in with "The Fighter," saying: We measured the space between Waylon and Willie/ And Willie and Waylon and me/ But there wasn't nothin' like Billy Joe Shaver/ Where Billy Joe Shaver should be.

By 1979, Willie, Waylon and Kris were well on their way to becoming legends, while Shaver was strung out and barely hanging on. He burned out for good when an angel appeared at his bedside after a long night of partying. It didn't say anything, he recalls, just sat there shaking its head. He wasn't sure if it was a hallucination or a vision, but he took the hint and drove off in his pickup. That night, while wandering the cliffs above the Narrows of the Harpeth River, he came up with the phrase, "I'm just an old chunk of coal, but I'm gonna be a diamond someday." That became the title of one of his most enduring songs. (John Anderson took it to No. 1 in 1981 and Johnny Cash later told Shaver that he sang it to himself each morning during a stint in rehab. It is also featured in the powerful closing scene of Pedraza's documentary.)

Shaver moved back to Texas the next day, quit drinking and confused the hell out of the music establishment. "It hurt me professionally, but I most likely would have died if I'd stayed. I had to walk away from it," he says now.

Shaver spent the next decade cleaning up and reordering his life. With little fanfare, he released three more solo albums and played around Texas with his son, Eddy, who had learned his guitar chops from Allman Brother Dickey Betts. Father and son formed an indelible bond. They called themselves Shaver, and Eddy's wailing solos gave the band's tunes a jolt of energy.

In 1993, the duo produced a rollicking roadhouse album, "Tramp on Your Street," that earned critical raves. They released two more albums in quick succession -- one of which, "Unshaven: Shaver Live at Smith's Olde Bar," was produced by Brendan O'Brien, who had worked with Pearl Jam and Stone Temple Pilots -- and a whole new generation of fans was turned on to Shaver's tunes. He was sober and playing music with his son.

That seems a lifetime ago now, the days before Brenda got sick and everything fell apart.

I went up on the mountain and looked down upon my life

I had squandered all my money, and lost my son and wife

-- From "Try and Try Again," 1998

It was 1997, and Shaver was in Louisiana, acting like a movie star. Duvall, who first met him in the late '80s while shooting "Lonesome Dove" around Austin, gave him a speaking part in "The Apostle." It's easy to see why Duvall is drawn to Shaver. Take Duvall's character in "The Apostle" and merge it with the self-destructive country singer he played in "Tender Mercies" and you've got a decent rendering of Shaver.

Duvall set him up in a suite, so Shaver invited Brenda to come stay with him. They were divorced for the second time, but he'd heard she was not doing well. When she showed up overweight and grumpy, he forced her to go to the doctor: She had advanced rectal cancer, which required multiple surgeries. Shortly thereafter, when her diagnosis became terminal, they married for the third time. Shaver put his career on hold and stayed with her, cleaning out the wound in her side and holding her hand as she slowly died.

"It was rough, man, but I was glad to do it," he says. "I loved her, you know? We both realized we loved each other, after all that time of bouncing back and forth." (Other times, Shaver says he wonders if Brenda truly loved him, a doubt exacerbated by a cache of letters he found after she died. He says he asked her before she died, and she merely smiled at him.)

At the same time, Shaver's mother, who lived across town in Waco, was also suffering from cancer. Within a month, Brenda died at the age of 54 and Shaver's mother, Victory, died at 80. As hard as the loss was for Shaver, it was harder for Eddy, who was already outpacing his father's hard-living footsteps. After his mother died, Eddy started shooting heroin. One stint in rehab didn't take. Shaver says he wanted to enroll Eddy in a new treatment center, but Eddy's new wife wouldn't allow it.

In late December of 1999, Eddy signed a contract with an Austin-based label to record a solo album. On New Year's Eve, while celebrating his new deal, Eddy overdosed and died in a Waco motel room. He was 38.

That night, Shaver was scheduled to play with Eddy at Poodie's Hilltop, a bar outside of Austin owned by Willie Nelson's road manager. Nelson, who'd lost a son to suicide on Christmas Eve several years before, filled in on guitar. When I ask Nelson about it, he chooses his words slowly, careful to protect a private moment between friends. "It was as sad as you can imagine," he says.

When our time has ended

And our race is over, run

We will melt into the likeness of our own beloved ones

-- From "Son of Calvary," 1998

Roseanne Cash, who knows of such things, once wrote that "at the heart of real country music lies family." It's certainly the heart of Shaver's music today. His recent songs are consumed with his performance as a father, husband and son. His last album, "Freedom's Child," features a song, "Day by Day," that might be his most personal to date. It tells the story of his family in nine verses, and it's so personal that Shaver has yet to perform it live. When I reach him by phone at his home in Hawaii, Kristofferson says it is the best exposition of family grief he's ever heard. And then he recites the lyrics from memory: There's many a moonbeam got lost in the forest/ And many a forest got burned to the ground/ The son went with Jesus to be with his mother/ The father just fell to his knees on the ground.

"The simple eloquence of that thing is just heartbreaking," Kristofferson says.

Shaver's continued brilliance as a songwriter, when most of his peers are retired or simply singing the same old hits night after night, is drawing notice. In 2002, in Nashville, he received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Americana Music Association, and stunned the assembled audience by announcing that it was the first award he'd ever received for his music.

Though he considered retiring after Eddy died, he eventually turned the other way and now works more than ever. He's on the road more than 200 days this year, despite suffering a heart attack onstage several years ago that culminated in a quadruple bypass. "I'm happiest when I'm playing," he explains. "It's a departure from the ordinary, I guess."

He is working on the songs for his next album with Houston-based Compadre Records, and plans to go into the studio with Kid Rock later this year.

Pedraza, an Argentina native, met Shaver eight years ago on the set of "The Apostle." She says she was captivated by the songs he played for the cast and crew, even though she does not consider herself a country music fan. "His music really moved something inside me," she says. "I just had to know: Who was this man who writes these amazing songs?"

The message of the film, she says, is the lesson of Shaver's life: perseverance and survival.

"You have to keep trying in life. The challenge is what you do with what you have. I find him a very humble guy, without bitterness, when he has every right to be bitter. His life could be so much more tragic. He takes it for granted but you have to have a lot of strength to come through all that."

Shaver is becoming something of a Hollywood favorite. Luke Wilson cast him in his upcoming film "The Wendell Baker Story" and has become a regular at Shaver's shows, frequently with other celebs in tow. Wilson didn't show for the after-party for the documentary at an Austin restaurant, but Duvall and Pedraza welcomed Dennis Hopper, Janine Turner and a crowd of about 100 other friends.

Despite a voice sore from four days of traveling around the state promoting the film, Shaver played an energetic 90-minute set with his band, dancing and waving his chocolate-brown cowboy hat in the air. Those who know him well agreed that he was in better spirits than he'd been in some time. "I want to thank Robert and Luciana for everything they've done for me," he said during his final encore. "I feel like a new man. I don't know if it's a better one, but at least it's a new one."

Shares