Former Army Capt. Jennifer Machmer was sexually assaulted three times before she left the military in early 2004. She was first molested in 2001, by a serviceman when she was a platoon leader in Poland; she reported the assailant and, as his superior, had him transferred. The second incident was in May 2002, when she was assaulted by a military chaplain she'd turned to for counseling for her failing marriage. Rather than complain, Machmer steeled herself to move on and forget the incident. Then, a month into her tour in Kuwait in 2003, she was raped by a master sergeant she knew well. "There was no way I could file away another sexual violation to myself, so I reported it within a half-hour," Machmer told the Women's Caucus congressional hearing on women in the military more than a month ago. "The aftermath of reporting has been terrifying." Terrifying because authorities questioned whether the assault should be considered rape; terrifying because she had no immediate counseling and had to continue to work in the same area with the assailant -- who was never prosecuted. Against her will, she received a medical discharge citing post-traumatic stress disorder, and had to argue for a good disability package during a formal hearing. In the end, it was Machmer, and not her assailant, who had to leave the military.

Cases like Machmer's, along with scores of other sexual assault scandals within the military, compelled the Pentagon to release a 99-page report last Thursday ("The Department of Defense Task Force Report on Care for Victims of Sexual Assault"), ordered in February by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, detailing how the U.S. military has mishandled sexual assault cases within the ranks. At the same time the Pentagon is being slammed for leadership failures in the Abu Ghraib prison abuse controversy, advocates for women in the military are railing against the Pentagon for releasing a report that neglects to make concrete recommendations on the problems of sexual assault within the military and, instead, asks for further summits to discuss the problem. Amnesty International released a response to the report last Friday: "While the review was an important step, years of sweeping this problem under the carpet and systematic silencing of its victims cannot be erased with yet another report."

The recently released report is hardly the whistle-blower that exposes the military's sexual abuse scandals. Since 1986, there have been dozens of other official reports on sexual harassment in the military -- with few major changes implemented in the services. "The military has set up a task force to study the issue and it's come to the same conclusions," says Rep. Louise Slaughter, D-N.Y., co-chair of the Congressional Caucus for Women's Issues. "It's almost as if they think that if they can throw out enough information, things would be different -- but they're not."

Kate Summers, director of services for the Miles Foundation, an advocacy organization for military women who have been assaulted by fellow troops, says that the Defense Department's report "has substantiated the information available to this office, such as the military's failings to provide timely services, and substantiates the surveys that veterans have made, and the anecdotal evidence made by victims for decades. But as far as recommendations, it asks for meetings. Meetings and conferences do not constitute a plan of action."

Researched by an eight-member task force over a 90-day period, the Defense Department's current report concludes that there were more than 1,000 cases of reported sexual misconduct in the military in 2003, and 900 in 2002. (These figures are assumed to represent only a small fraction of the assaults, because of many victims' reluctance to come forward for fear of being stigmatized by their fellow soldiers.) According to the report, protective measures for victims are "inconsistent and incomplete"; the report calls for more education and programs to deal with sexual assault cases. Advocates argue that the report barely addresses how to implement the major reforms needed to transform the military into a safer environment for integrated troops -- like hiring a program manager to oversee sexual abuse cases, staffing victim advocates and establishing a chain of command for ensuring victims' privacy.

Irene Weiser, director of the advocacy group Stop Family Violence, compares the violations against servicewomen to the Abu Ghraib scandal. "Women service members are being brutally assaulted in ways that are every bit as dehumanizing and agonizing as the assaults on prisoners in Abu Ghraib," she says.

The report found that there are no standardized programs to prevent sexual violence against women, nor is there a senior-level person at the helm to deal with the issue. The military doesn't even have a uniform definition of what constitutes sexual assault, sexual trauma or harassment -- which, the report states, has created challenges when trying to report statistics and evaluate programs. (With more than 40 previous reports, one would think a definition would have been established.) The military's response to victims is severely deficient as well, according to the report -- failing to provide even basic medical care, such as testing for HIV, rape evidence kits and proper counseling for victims. Other troubling findings include a lack of confidentiality for victims and a failure to sufficiently prosecute attackers, allowing them not only to walk free but to work in the same environs as their victims. This is especially so in combat, the report says, where there are "heavy investigative workloads and insufficient on the ground resources." The task force does address the lack of confidentiality, but advocates say that immediate provisions must be made so victims' privacy will be safeguarded and other troop members who have been sexually violated will feel comfortable enough to come forward.

"If a woman reports, it's the peers who get her in trouble. It's never a stranger who commits sexual assault -- it's always someone they know, someone who they've been drinking with. It's usually the peers who say, 'Shut up and don't get him into trouble,'" says Lory Manning, who directs the Women in the Military Project at the Women's Research and Education Institute.

Prosecutions must be expedited as well, so that the accused attacker is immediately removed from the victim's surroundings, argue advocates. "They have to immediately remove the sexual perpetrator from the scene. One woman said that every day she had to salute the man who raped her," says Slaughter.

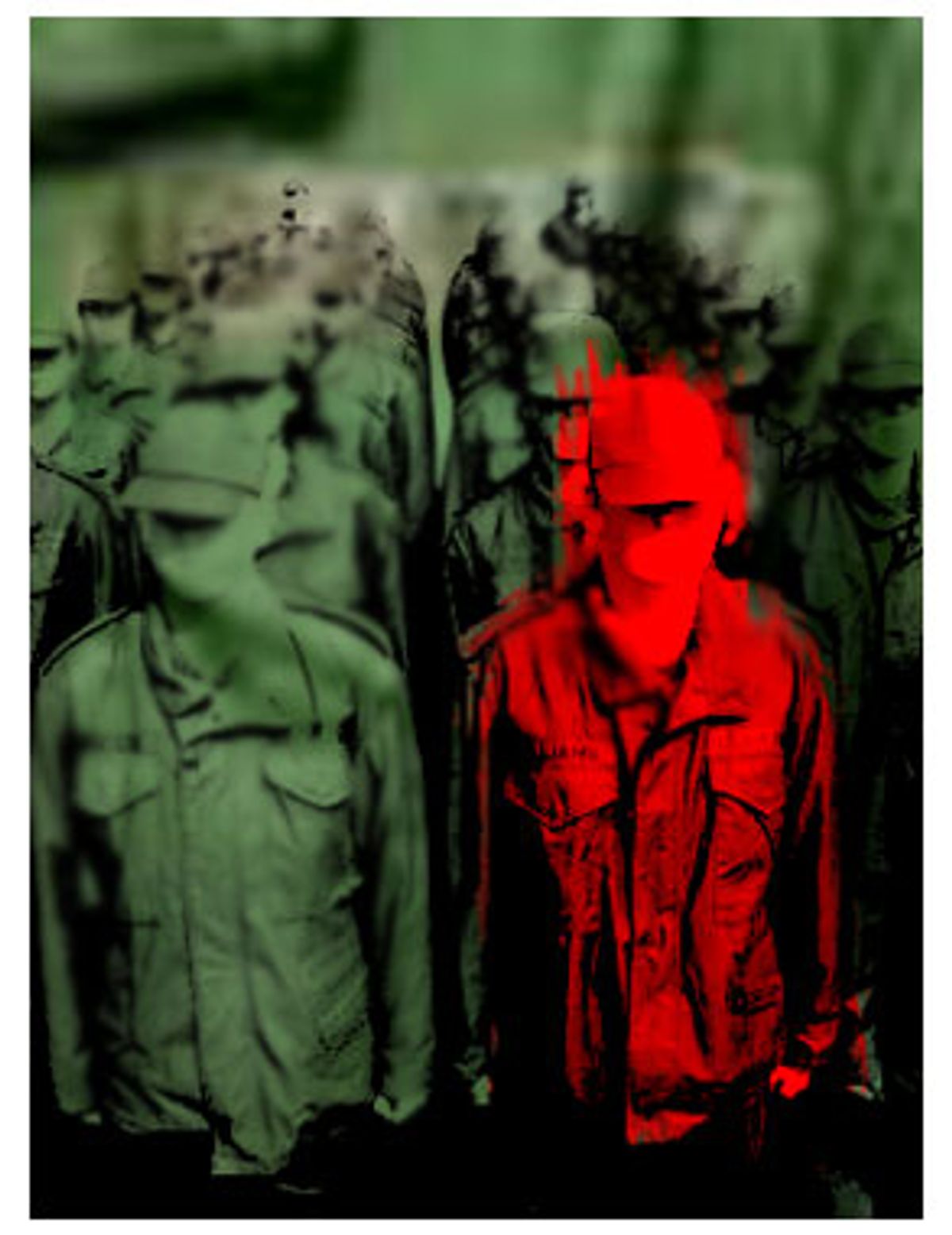

Ever since Bill Clinton opened up 90 percent of military jobs to women in 1994, over 15 percent of troops in Iraq are women. That means more than 212,000 females are currently serving in the military. Despite this, the "boys will be boys" mentality that allows for sexually abusive behavior to go unpunished is still very much intact in the military. According to Duke University law professor Madeline Morris' 1998 essay "By Force of Arms," published in the Duke Law Journal, the crime with the highest rate in the military is rape. "The ratio of military rape rates to civilian rape rates is substantially larger than the ratio of military rates to civilian rates of other violent crime," writes Morris. "Masculinist elements of the military culture should be replaced by an ungendered vision ... integrated units would have to be carefully shaped as a band of brothers and sisters," writes Morris.

Slaughter, who says Congress is researching a bill to implement more direct changes in the military, agrees that it's the culture that needs overhauling: "It's a culture of competition. We heard from many women who say that's the issue -- one way to put an uppity woman in her place is to sexually assault her, humiliate her."

The tortures in Abu Ghraib and the sexual abuse against servicewomen within the ranks may be connected because it stems from a military culture that allows for sexualized abuse. Says Kate Summers, "There are definitely intersections between the sexual assault in Abu Ghraib and the abuse against women -- which is the gendered violence, as well as the issue of leadership response."

But advocate Weiser is careful to separate the issues, noting that the sexual assault against servicewomen was a failure in leadership, whereas Abu Ghraib was an issue of leadership encouraging and authorizing that kind of abuse. Still, she retorts, "Maybe after 15 years of reports that go nowhere, the first action that is needed is to send our women service members digital cameras."

Shares