There is no shortage of comparisons between our current military misadventures and Vietnam. But after watching "RFK," David Grubin's powerful new documentary on the life of Robert F. Kennedy set to air on PBS in October, I feel there is a more useful comparison -- not of the two wars but of two eras and two leaders.

John Kerry has said that he would one day like to write a book titled simply "1968." In fact, it was impossible to watch "RFK" and not be struck by the many historical parallels between 1968 and today, by how much the legacy of Bobby Kennedy animates John Kerry's run for the White House -- and how Kerry is in a unique position to complete Kennedy's unfinished mission of ending a misguided war, returning real compassion to our domestic agenda, and bringing us together as a nation.

"As a survivor of RFK's 1968 campaign," historian Arthur Schlesinger told me, "I see John Kerry in the JFK/RFK tradition -- a brave, intelligent and thoughtful man. I find many similarities between that campaign and this one, especially our entanglement in a hopeless war at the expense of urgent domestic woes."

In the film, former Sen. and RFK confidant Harris Wofford says that Kennedy told him that he was running for president "to save the soul of the country."

Kerry has already fueled his campaign with similar aspirations. "America is more than a piece of geography," he said in a speech earlier this month, "more than the name of a country. It is the most powerful idea in human history: freedom and equal opportunity for all ... I am running for president to renew that idea and spirit again."

And not a minute too soon. You know the idea and spirit of America are in desperate need of renewal when the most stirring rallying cry we can muster these days is, "At least we don't behead people!"

It should go without saying that we're better than that. Better than an imperial, unilateral foreign policy. Better than domestic policies driven by selfishness and greed. Better than Abu Ghraib. Better than 43 million uninsured. Better than 12 million children living in poverty. Better than millions of school kids left behind.

The 2004 election is our chance to prove to ourselves and to the world what America really stands for. This election is a referendum on our future: Are we a nation based on hope and promise, or a nation based on fear?

"People are selfish," Kennedy told speechwriter Richard Goodwin as he agonized over whether to seek the presidency, "but they can also be compassionate and generous, and they care about the country. But not when they feel threatened. That's why this is such a crucial time. We can go in either direction. But if we don't make a choice soon, it will be too late to turn things around. I think people are willing to make the right choice. But they need leadership. They're hungry for leadership."

In 2004, we're downright starving for it. Real leadership. From leaders who don't tell people what their pollsters tell them the people want to hear. Leaders who capture our imagination and challenge us. Leaders who can transform our country through hope instead of demeaning it through fear and division.

John Kerry can be that kind of leader -- as he's demonstrated in his recent calls for shared sacrifice and national service. "America needs you on the front lines," he recently told graduating seniors at New Orleans' Southern University. "We need you to give some of your time and energy to the great cause of reducing illiteracy, preserving our environment, providing after-school care, helping our seniors live in dignity, building new homes for those who need them -- and in all of this, building a nation that really is one America."

In fact, it was Kerry's ancestor, John Winthrop, who founded Massachusetts and coined the political ideal of a "shining city upon a hill" -- a vision that then became associated with the Kennedys and Camelot. John Kerry could lead us back to that noble ideal for American democracy.

So why then is Kerry still neck-and-neck in the polls with George Bush, whose idea of transformational leadership consists of turning his "base" -- very rich people -- into even richer people?

The problem is that Kerry is still only doling out his vision in drips and dribbles. He has not connected the dots with a bold narrative. He has not yet shown Americans how he will lead the country forward and fulfill the promise the Kennedys made to the nation.

The irony is that the Kerry narrative is one of the great narratives in the history of American politics -- a personal tale that links his life story to the history of our times, to his vision for the renewal of America. For starters, there is the fact that -- unlike so many of those hawkish deferment junkies in the Bush administration -- Kerry actually volunteered to serve his country, inspired in no small part by President Kennedy's call to national duty and his heroic service in World War II aboard PT-109.

Kerry's life shows the courage it takes to get America back on track, and to end our national detour into fear. The courage to stand up for what's right, and speak unpopular truth about what's wrong.

Kerry's political narrative starts on June 5, 1968 -- the night Bobby Kennedy was assassinated: John Kerry is on board the USS Gridley, returning home from Vietnam. He carries with him a dog-eared copy of RFK's political manifesto "To Seek a Newer World." During the last month, Kerry has been using the ship's radio to follow Kennedy's remarkable campaign run. But when he tunes in to hear the results of the California primary, the crackling radio delivers the horrifying news that Bobby has been gunned down -- news that rocks Kerry to his core. "It was strange," he says, "coming home from a place of violence to a place of violence ... a violence that shook our very sense of the order of things."

This was the beginning of his coming of age as a leader, which culminated three years later with his 1971 testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. With the help of former RFK speechwriter Adam Walinsky, Kerry crafted a compelling, unflinching speech filled with all the moral clarity, fearlessness and boldness our current times demand. "How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?" memorably asked Lt. Kerry -- wrenching words just as applicable to today's Iraq as they were to Vietnam in '71.

RFK's influence can also be seen in Kerry's willingness to dream big. His campaign speeches often consciously evoke Bobby's famous challenge to dream of things that never were and ask, "Why not?": "Why not give every working American access to high-quality, affordable healthcare? Why not have public schools where children set out on a lifetime of learning and possibility? Why not preserve our environment so our great-grandchildren can breathe clean air and drink clean water? Why not have a leadership committed to civil rights, equal rights and affirmative action? And why not have a foreign policy that strengthens our nation and our interests by advancing our values?"

The hallmark of Robert Kennedy's presidential campaign was the urgency he brought to the problems of race and poverty. And as Douglas Brinkley wrote in "Tour of Duty": "Like Robert F. Kennedy, for a young white man of privileged background, Kerry always displayed an uncommonly incongruous instinct for siding with the underdog."

Speaking this week in Topeka, Kan., on the 50th anniversary of the Supreme Court's landmark Brown school desegregation ruling, John Kerry echoed Kennedy's concerns:

"We have not met the promise of Brown when one-third of all African-American children are living in poverty. We have not met the promise of Brown when only 50 percent of African-American men in New York City have a job. We have not met the promise of Brown when nearly 20 million black and Hispanic Americans don't have basic health insurance. And we certainly have not met the promise of Brown when, in too many parts of our country, our school systems are not separate but equal -- but they are separate and unequal ... For America to be America for any of us, America must be America for all of us."

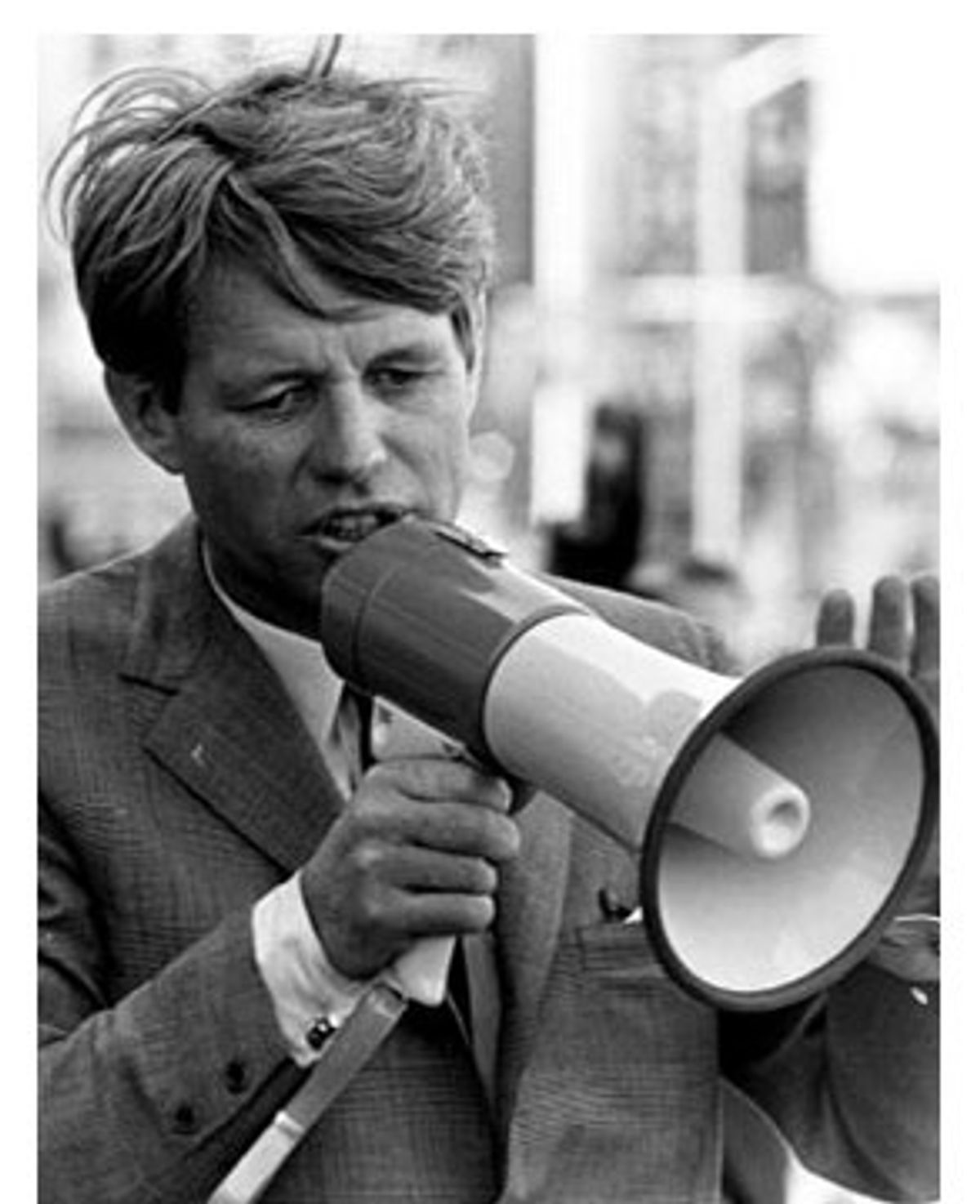

There is a memorable moment in the PBS documentary when Bobby Kennedy makes one of his first campaign appearances in the Midwest, at the University of Kansas, in front of a jampacked audience that responds to his call for abandoning "the bankrupt policies we're following at the present" with thunderous cheers.

A photographer for Life magazine traveling with Kennedy can't believe what he's seeing. Walinsky recounts how the man turned to him and yelled: "This is Kansas, fucking Kansas ... He's going all the fucking way!"

Kennedy's ability to move beyond divisions that threatened to tear our country apart and reach out to all Americans -- black and white, rich and poor, young and old, urban and rural -- meant that every place, even a bastion of conservatism like Kansas, was suddenly in play. Every state was a swing state.

Now, John Kerry has the opportunity to draw a clear line between the politics of hope and the politics of fear. If he does, and offers a bold vision forged by his unique personal narrative to connect with, inspire and empower voters all across the country, he too can catch fire and turn red states blue -- winning not in a tossup, but in a landslide.

Shares