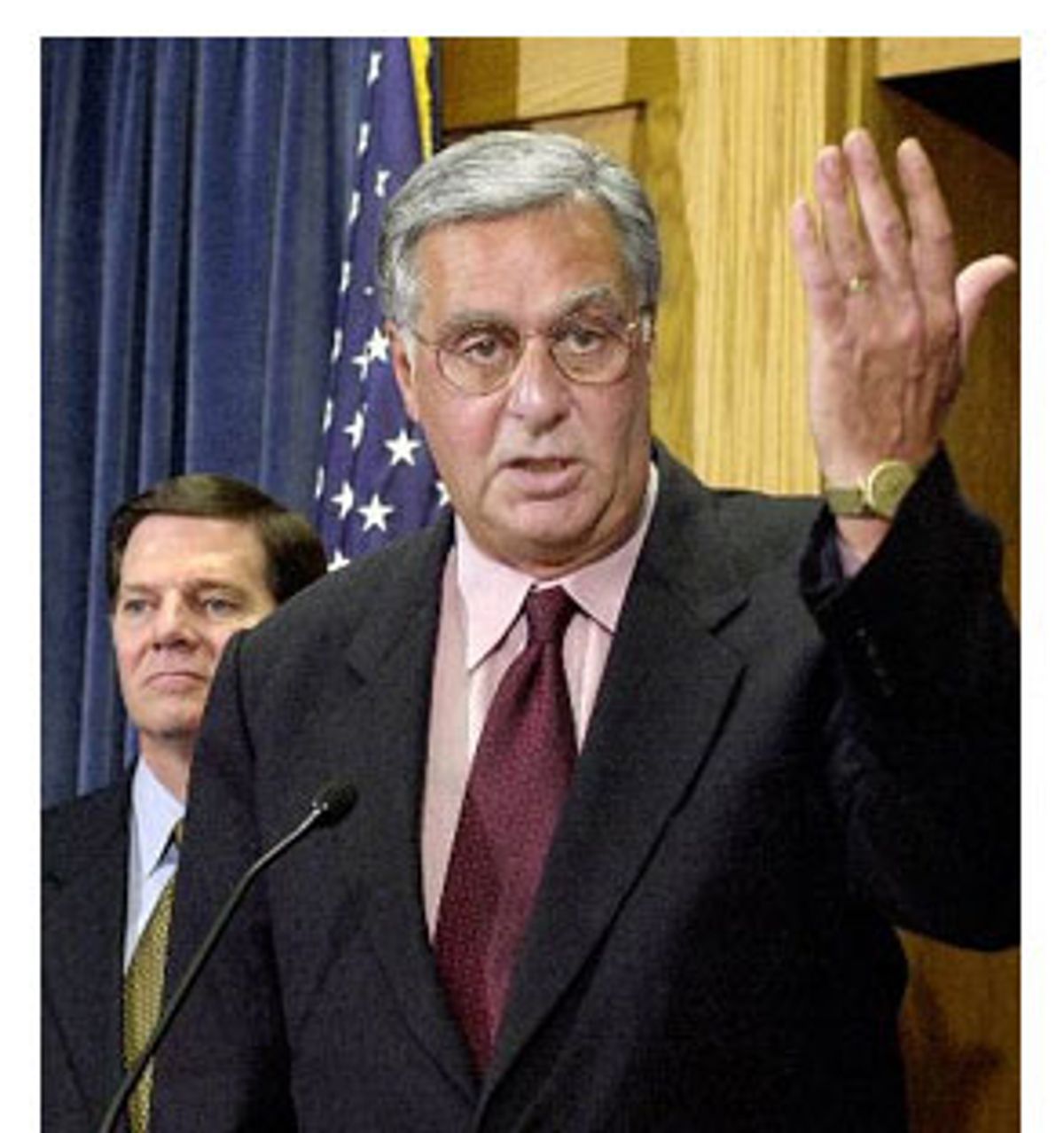

When former House Republican Majority Leader Dick Armey's official portrait was unveiled at a reception in the Capitol's Statuary Hall last month, Speaker Dennis Hastert delivered a praiseworthy little speech, as did Armey's longtime policy nemesis, former House Democratic Leader Dick Gephardt of Missouri. "I was tickled with Dick Gephardt's generosity," Armey said in an interview with Salon. "He was very nice. He said he couldn't resist being there to hang me."

But one dignitary was conspicuously absent: House Majority Leader Tom DeLay. "I asked that he speak," Armey said. "Who'd be the most natural guy after the speaker? He is the guy that I came in with -- we were part of the celebrated 'Texas Six-Pack' of 1984. He is the most senior member of the House from Texas, and he is my successor. He was invited, and he declined."

Once good friends, the two Texas Republicans -- whose relationship was badly strained by the fallout from a botched 1997 coup attempt against then Speaker Newt Gingrich -- have now dropped all pretense of collegiality. Because they were leaders of the House GOP during its headiest days, their enmity is more than a personal drama; it is a metaphor for the troubled legacy, 10 years later, of the 1994 Republican "revolution" that brought them into power.

For the first time since the Eisenhower administration, Republicans control all of Washington, from the White House to both chambers of Congress. Yet the party of limited government has, under President Bush, instead presided over a massive expansion of government spending. New spending on defense and security was inevitable after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, Armey conceded. But there is no justification, he said, for the budget-busting Medicare prescription drug program, the largest new entitlement since Lyndon Johnson's Great Society, which will saddle the government with $8.1 trillion in unfunded liabilities over the next 75 years. Record deficits threaten the cherished Bush tax cuts, he added. Even the corporate-welfare farm subsidies that Armey, as a free-market conservative, had fought to kill are back. The moves all have one thing in common, he asserted: They are designed to secure votes.

"We're letting the political hacks overrule the policy wonks in this town," Armey lamented to me. Republican principles are being sacrificed in the pursuit of short-term political goals, he complained. And the irony, he added, is that all the maneuvering for votes may instead end up costing Republicans at the polls this year if disgusted fiscal conservatives simply stay home. A spokesman for DeLay declined to comment for this story.

Armey's stature as a former House leader lends his critique special weight. But most remarkable is that he is willing to make it at all. While many House conservatives say privately that they feel helpless in sticking up for their principles in the face of ruthless intimidation from the Bush White House and DeLay, few have dared to speak as boldly as Armey has. DeLay, who is known as "The Hammer" for his ability to pound Republicans into supporting the party line, doesn't just discourage dissent, he beats it to a pulp. And the "with us or against us" mentality, once directed only toward terrorists and Democrats, is increasingly targeting conservative dissenters as well.

During last fall's battle over Medicare prescription drug benefits, for example, DeLay engaged Stuart Butler, a vice president of the conservative Heritage Foundation, in an oddly personal debate at a meeting of the Republican Study Committee, a group of 50 House conservatives. DeLay ridiculed the venerable think tank's research as uninformed. (Its insistence that the Bush administration was low-balling the bill's costs turned out to be correct.) His attacks were so aggressive -- "name-calling," as one attendee described it -- that many Republicans left muttering that DeLay had crossed a line.

And in March, at a meeting of all the House Republicans, DeLay slammed Armey for having said publicly that high deficits will make it harder to make the Bush tax cuts permanent. "It would seem to me that I stated the obvious, but it was apparently something that offended him deeply," Armey said.

Although he is out of Congress and the GOP leadership, Armey makes his comments at some personal risk; he is now a lobbyist on Washington's fabled K Street, which is ruthlessly patrolled by DeLay and his key ally, Americans for Tax Reform president Grover Norquist. For years, Norquist and DeLay have worked to purge the nation's corporate lobby shops of Democrats, and companies that fill GOP campaign coffers with money are rewarded with access to lawmakers. Enemies don't get their calls returned, and without access, they lose clients. Access is coordinated by the White House, often through the office of another powerful Texan, political strategist Karl Rove.

For two years, the assistant who answered Rove's phone was a woman who had previously worked for lobbyist Jack Abramoff, a close friend of Norquist's and a top DeLay fundraiser. One Republican lobbyist, who asked not to be named because DeLay and Rove have the power to ruin his livelihood, said the way Rove's office worked was this: "Susan took a message for Rove, and then called Grover to ask if she should put the caller through to Rove. If Grover didn't approve, your call didn't go through."

Observers of Washington's lobbying scene who know how DeLay plays the money game wonder if the majority leader had a hand in a recent decision by the state of Texas to cancel a $180,000-a-year contract with Armey's law firm, Piper Rudnick. Texas' stated reason for the pullout was that Piper Rudnick had created a conflict of interest by agreeing also to represent the state of Florida. However, the Florida contract is for lobbying to prevent military base closures; the contract with Texas specifically excluded work on base closings.

Texas is also represented in Washington by the Federalist Group, which employs a former DeLay aide. A spokesman for DeLay said the majority leader had nothing to do with Texas' decision to drop the Piper Rudnick contract. Armey declined to comment on the matter, saying only that DeLay doesn't scare him. "There's only one person in this town who won't take my calls, and I wouldn't call him anyway. You can't hurt a man who don't give a damn."

Armey was an economics professor at the University of North Texas when, after watching Congress on C-Span, he decided to run for the House of Representatives in 1984. Armey "got into Congress not because he wanted to become a political figure, but because he saw it as the best way to achieve his strongly felt policy goals," said congressional analyst Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute. Armey subsequently built a dedicated following for his unwavering conservative economics: free markets, less government regulation and a simplified "flat tax." And Armey was not above hurling insults at the most despised liberals. He once called Rep. Barney Frank, D-Mass., "Barney Fag" (Armey insists that he misspoke) and former first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton a "Marxist."

DeLay, who owned a pest control business in Sugar Land, Texas, before his election to Congress, was never one of the conservative movement's intellectual lights. He excelled at the mechanics of politics: cutting deals, counting votes, raising money. And although the two friends shared a deep opposition to abortion rights and gay rights, religious-right issues were never Armey's passion. DeLay once declaimed from a church pulpit that God was using him to advance a "biblical worldview," and that he had pursued the impeachment of President Clinton because he had the "wrong worldview." Armey generally left God out of his public pronouncements, quoting not the Bible but Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson.

In 1994 Gingrich put Armey in charge of drafting the "Contract With America," the Republican campaign manifesto that unexpectedly helped propel the minority GOP to power that November. Gingrich found himself speaker, Armey ran unopposed for majority leader and DeLay fought his way into their circle by winning a three-way race for House whip, prevailing over Gingrich's closest friend in the House, Rep. Bob Walker, R-Pa.

By 1997, however, things were falling apart. Egged on by fiscal militants, Gingrich had pursued an unpopular partial shutdown of the federal government in the winter of 1995-1996 rather than approve President Clinton's budget. Gingrich's leadership became increasingly autocratic and erratic, and DeLay and then Rep. Bill Paxon, R-N.Y., hatched a failed plot to oust him. Armey's role in the plot remains murky. He insists he was not part of the coup and instead tried to warn Gingrich. But many rank-and-file Republicans did not believe him. At the time, Armey was also under assault from conservatives for cutting deals with the Clinton administration as majority leader, and after the coup craziness, Armey's support eroded. With the position of speaker out of his grasp, he retired from Congress in January 2003 after nine terms.

Now, in addition to his lobbying work, Armey is chairman of Citizens for a Sound Economy, a conservative, grass-roots, free-market advocacy organization. During travels last fall to promote his new book, "Armey's Axioms: 40 Hard-Earned Truths From Politics, Faith, and Life," the former majority leader said he found conservatives in the heartland to be discouraged by the enormous expansion of public spending and record budget deficits. "Wherever I went," Armey said, "I had people who were the natural constituency of the Republican Party say, 'Oh, the heck with it. I'll just stay home.'"

In a close presidential election, such GOP disaffection could prove decisive, he argued, a bigger factor undermining Bush than Ralph Nader might be for John Kerry. "You've got the Kerry people worried sick about the possibility that Nader might take 3 percent of their vote. But I think the Bush folks need to say, 'Well, how do we survive if 3 or 4 or 5 percent of our foundation base just decides to sit out the election?"

Echoing Armey, pollster John Zogby said he has heard the same anecdotal evidence of Republican disenchantment. "Today I'm in Austin, Texas," Zogby said in a phone interview, "and my driver said, 'I've been a Republican all my life, but I can't support him [Bush].'"

Polling data is beginning to reflect the souring mood, he said. In a survey of likely voters taken May 10-13, Zogby found that President Bush had the support of 71 percent of self-described conservatives, but 19 percent were for John Kerry. "That's really intriguing to me because the president and the administration have spent the last four years shoring up their conservative base," Zogby said. "But the tide may be going back out for them."

In Armey's view, hardball players like Rove and DeLay have lost perspective in their single-minded pursuit of power. The signal case is Medicare, he said. Desperate to co-opt one of the Democrats' strongest campaign issues, the White House made passage of Medicare prescription drug benefits one of its top priorities. But the seniors whom the bill was meant to win over are in revolt, perplexed by the program's complexity and worried that it will encourage employers to drop private drug coverage from retirement benefits. Kerry holds a 20-point advantage over Bush in key battleground states on the question of who would better handle the rising costs of prescription drugs, according to a joint poll conducted last month by the Republican Tarrance Group and the Democratic firm of Lake, Snell and Perry.

On the day the prescription drug bill came before the House for final passage last November, Armey published an Op-Ed in the Wall Street Journal urging lawmakers to vote against it. "I believe that good policy is good politics," he wrote. "This is a case where bad politics has produced a bad policy proposal. Conservatives would be smart, and right, to reject it." Armey's breaking ranks incensed DeLay and Speaker Hastert, who were straining to ram the bill through.

Armey's encouragement of a mutiny may well have contributed to the extraordinary events on the floor of the House. Fiscal conservatives resisted "The Hammer," prompting Republican leaders to hold open a 15-minute vote for an unprecedented three hours, from 3 a.m. to dawn, as DeLay and other leaders pounded the holdouts. "There was a lot of heavy-handed, mean-spirited whipping going on," Armey said. In the end, the bill squeaked through.

Afterward, Hastert told Armey he was furious at his meddling, but the two made up. "It's always a healthier thing when two people who have a disappointing experience between them meet to say, 'Hey, my good friend, I know I let you down,'" Armey said. But there was no reconciliation with his fellow Texan. "Tom DeLay somehow saw it as a betrayal on my part, and he's not so quick to patch things up," Armey said.

In the long run, Armey says, Republicans will be stronger if they allow genuine internal debate. But that is hardly the trend in the House, where DeLay "has taken every norm the Legislature has operated on and shredded it," the AEI's Ornstein said. Once, Republicans lambasted Democrats, when they were in the majority, for denying them the opportunity to amend bills on the House floor. Today, congressional leaders have gone even further by barring Democrats from participating in key conference committees, where final deals on legislation are worked out. In Texas, DeLay engineered a mid-decade redistricting of congressional seats designed to oust incumbent Democrats, breaking the tradition of realigning only after a 10-year census. "On a scale of 1 to 10, Democrats abused their majority status at about a level 5 or 6," Ornstein observed. "Republicans today have moved it to about an 11."

And in a symbolic obliteration of Armey's influence, DeLay took over a Web site Armey had used to promote his prized flat-tax proposal when he was in Congress. The URL -- www.freedom.gov -- remains the same. But now the site contains propaganda about the "Victory in Iraq."

Armey opposed the invasion. In August 2002, he met separately with Bush and Vice President Cheney in an attempt to talk them out of it. "I said, 'This has the potential to be an albatross at election time.' I was so desperate that I quoted Shakespeare instead of Jimmy Buffett," he said. "I don't know the exact quote. Something like, 'Our fears betray us,' or 'Our fears make cowards of us all.'"

While he believed that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction and links to terrorist organizations, Armey did not agree with the administration's assessment of a dire and imminent threat. He said he told Bush and Cheney that it was "against the character of our nation" to strike a country that had not attacked first. Liberating the Iraqi people was the more resonant argument, Armey said, because it was in keeping with American principles. But that, of course, was not the stated reason for the war; had it been, it's unlikely Americans would have supported the invasion.

Similarly, Armey said Congress probably would not have approved the Medicare bill had all relevant information been known before the vote last fall. Medicare's chief actuary, Richard Foster, revealed after the vote that the Bush administration had threatened to fire him if he informed Congress of his true, higher cost estimate: not $400 billion but as much as $600 billion over 10 years.

If, by speaking out, Armey hopes to embolden his former colleagues to stand up to DeLay's bullying, it's not clear he will succeed. In interviews last week, several of the conservatives who voted against the Medicare bill were reluctant to say anything that might draw DeLay's wrath. And Armey's critiques do not sit well with others among his former Republican colleagues, some of whom view him as a hypocrite. "What did Armey do when he was in office to restrain the growth of government?" asked Rep. Ray LaHood, R-Ill. "He led the floor debate to create the Department of Homeland Security. I would say he contributed to the growth of government."

Unlike DeLay, Armey, who now demands simon-pure conservatism, voted for final passage of the No Child Left Behind Act, the Bush-backed education reform much reviled by many on the right as meddling by the federal government in state and local matters.

To his critics, Armey says that's precisely why he left his job as majority leader. He was having to make even more serious compromises on policy under a Republican president than he did under Clinton, and he no longer wanted to have to take party positions contrary to his philosophy.

"There's a marvelous song by John Denver," he said, paraphrasing the lyrics. "It goes: 'Some days are diamonds, some days are stones. There's a face I see in the mirror, more and more is a stranger to me, more and more is the danger of becoming what I thought I'd never be.'"

"When you wake up and see that stranger in the mirror," he said, "that's when you know it's time to go."

Shares