Ahmed Chalabi is gone from the Pentagon's hall of heroes at last. But John Negroponte is still on track to become the Bush administration's viceroy as U.S. ambassador to Iraq come the transfer of sovereignty scheduled for June 30. What sort of diplomatic post is it going to be? Recent history provides some very strong pointers. And they suggest that the abuses exposed at Abu Ghraib prison could be, rather than an aberration, a warm-up for fun and games yet to come.

The same veteran cold warriors who provided a respectable political shield for the armies of Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala in their slaughter of thousands of Maya Indians 20 years ago have been painstakingly put into place to provide acceptable cover for the "pacification" of Iraq following the June 30 transition to supposedly democratic rule.

The previous careers of some of the key Bush officials appointed to oversee policy in Iraq leave little doubt about how far they are willing to go. In the past they have gone that far and beyond, without limit. They have countenanced, covered up, excused and turned a blind eye to the killing of hundreds, even thousands, including the indiscriminate murder of women and children. It is an indisputable matter of public record.

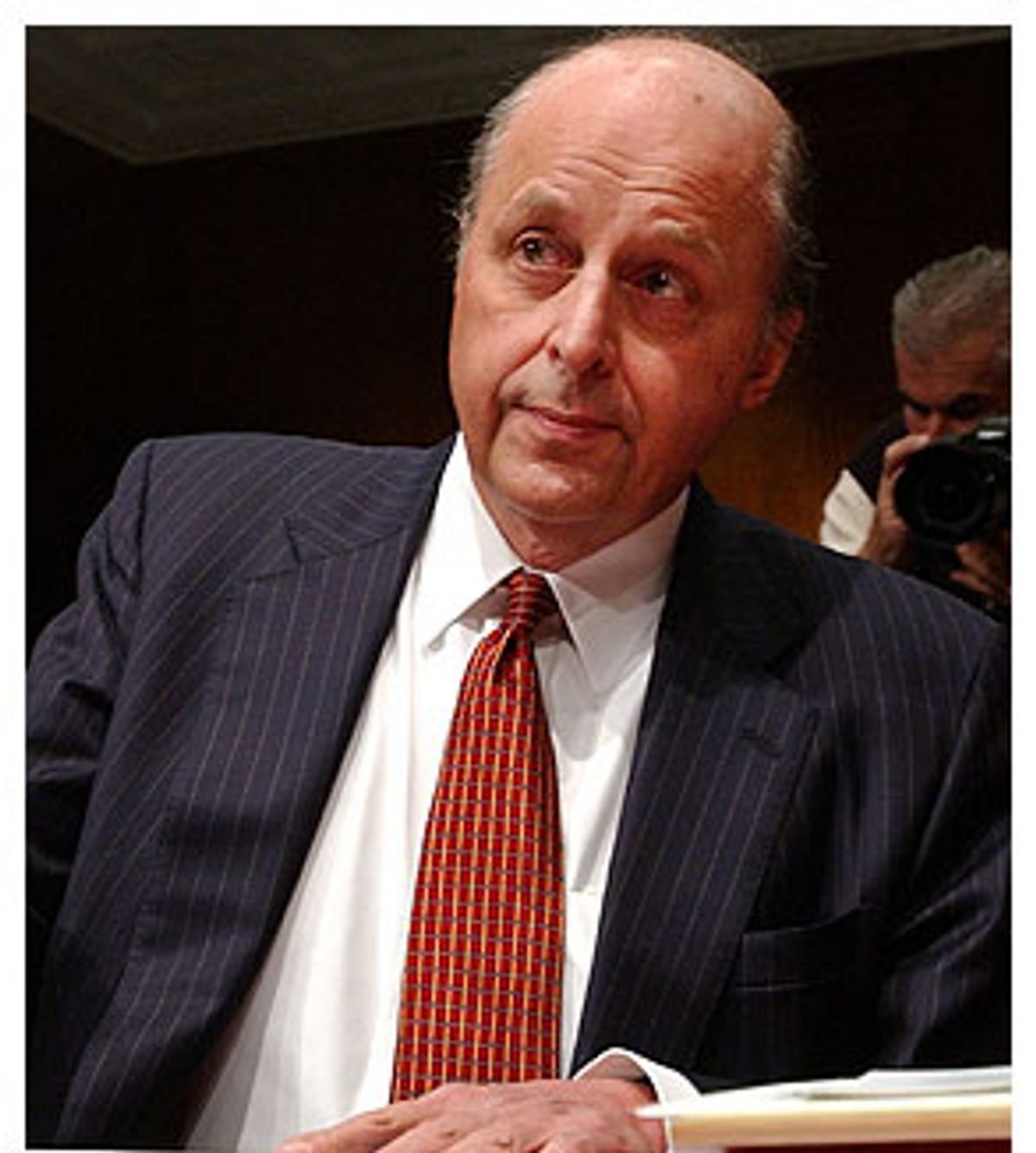

The selection of Negroponte, most recently the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, has been presented in the U.S. media as a triumph of moderation and internationalism in the Bush administration's quavering policy toward Iraq. Negroponte's key qualification for his new assignment is supposedly his success in working with diplomats from other nations at the U.N.

But Negroponte above all else is an old Central America hand from the darkest chapter of the Reagan administration's policy of confronting, containing and eventually rolling back left-wing guerrilla movements in the 1980s. He was U.S. ambassador to Honduras from 1981 to 1985 and oversaw the growth of U.S. military aid to the viciously repressive military government from $4 million a year to $77.4 million a year. Flouting an act of Congress, he created a covert scheme to funnel money to the Nicaraguan Contras through Honduras. Speaking of Negroponte and other U.S. officials working with him, a former Honduran congressman said, "Their attitude was one of tolerance and silence. They needed Honduras to loan its territory more than they were concerned about innocent people being killed."

Negroponte supervised the construction of the El Aguacate air base, the Abu Ghraib prison of its time, which critics charged was being used as a secret torture and murder center. It is also where Contra rebels were trained to fight Nicaragua's Marxist Sandinista government. In August 2001, excavations confirmed that the supposedly wild and paranoid rumors about torture at that prison were true. The remains of at least 185 people, including two Americans, were discovered there.

It is also a matter of record that Negroponte took no action to rein in, let alone expose, the activities of the Honduran armed forces' own special intelligence unit, Battalion 3-16. Indeed, he helped conceal its murderous activities, reportedly including the killing of U.S. missionaries, from Congress. Battalion 3-16 was trained by advisors from the CIA and the Argentine junta.

In 1981, 32 Salvadoran nuns and other women who fled to Honduras after the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero were "disappeared" while Negroponte was ambassador. He asserted he knew nothing about it. But in 1996 Jack Binns, President Carter's ambassador to Honduras, told the Baltimore Sun that the women were tortured and thrown from helicopters to their deaths by the Honduran secret police. Rick Chidester, a U.S. Foreign Service officer serving in the embassy under Negroponte who submitted the 1982 report to the State Department on the human rights situation in Honduras, said that he was ordered to remove all mention of torture and executions before it was sent to Foggy Bottom.

In 1982, the State Department's annual human rights report on Honduras, prepared by Negroponte, found "no evidence of systematic violation of judicial procedures" and praised the country's dictator, Gen. Gustavo Alvarez. The next year's report was even more positive, observing that there are "no political prisoners in Honduras." In 1988, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights reported that "there were many kidnappings and disappearances in Honduras from 1981 to 1984 and that those acts were attributable to the Armed Forces of Honduras." The CIA inspector general's heavily classified 1988 report said "the Honduran military [had] committed hundreds of human rights abuses since 1980, many of which were politically motivated and officially sanctioned." It noted that Negroponte actively discouraged U.S. Embassy officers from reporting these abuses.

When Negroponte was nominated by President Bush to be ambassador to the United Nations, Sen. Christopher Dodd, D-Conn., the most knowledgeable member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Latin American affairs, said: "Based upon the Committee's review of State Department and CIA documents, it would seem that Ambassador Negroponte knew far more about government-perpetuated human rights abuses than he chose to share with the committee in 1989 or in Embassy contributions at the time to annual State Department Human Rights reports."

Clearly, such a U.S. ambassador in Baghdad would not turn squeamish if either Chalabi, the Rumsfeld team's former favorite, or some lucky future "strongman" -- yet to be plucked from obscurity -- took such hard actions to stabilize Iraq.

Ironically, there are striking parallels between the background of Negroponte, who has devoted his life to rolling back the scourges of Central American rebels and now extremist Islamists, and the background of Chalabi, the convicted super-bank swindler who faces 22 years of hard labor if he ever makes the mistake of setting foot again in Jordan, where he was convicted of looting the Petra Bank.

Negroponte, like Chalabi, is the product of a sophisticated and cosmopolitan world of wealthy Mediterranean wheeler-dealers who made it big in Reagan-era Washington by promoting ruthless crusades in Third World countries that had suddenly become hot pawns for would-be master strategists.

Chalabi came from an elite Iraqi family that grew immensely wealthy under the sham democracy fostered by Britain in Iraq from the 1920s to the military coup of 1958. His family's fortune and his own intellectual brilliance got him into MIT, where he did very well.

Negroponte's father was a shipping tycoon from Greece. John was born in London, and the family migrated to the United States. Their wealth and Negroponte's own gifts propelled him to Exeter and Yale. He rose like a rocket in the Republican sphere of Washington in the 1970s and 1980s. As an aide to Henry Kissinger, who was President Nixon's national security advisor, Negroponte proved his bona fides as a tough guy of the right by attacking Kissinger as too soft on the North Vietnamese during the Paris peace talks.

Another man turns out to be the political and bureaucratic mentor and enabler of both Negroponte and Chalabi: the man who directed and protected the anything-goes counterinsurgency policies in Latin America in the 1980s, and who was rapidly advanced by the team of Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz to play a similar role for Iraq 20 years later -- our old friend Elliott Abrams, now senior director for Near East, Southwest Asian and North African affairs on the National Security Council.

Abrams, in the classic neocon style, is a "phony tough," to use the term coined by late, great columnist Stewart Alsop about the inept Watergate plotters led by Nixon. In Iraq as in Latin America, such people eagerly boast of their "realism" and "ruthlessness" -- the latter of which is only too apparent in their willingness to condone or provide political cover for human rights abuses.

For ideologues like Abrams, operators like Negroponte and Chalabi are essential. They can actually do the dirty work of dealing with tyrants and torturers face to face. The Negropontes of the world, of course, are not torturers themselves; they do not have to be. Their history is to protect and reassure with respectable political cover the people who are.

Abrams at first glance would appear to have zero qualifications for his latest assignment on the NSC. He has never even pretended to be a Middle East expert. But like Negroponte, Abrams turned a blind eye to human rights violations and the Geneva Conventions and chose to ignore, even deliberately mislead, Congress in his drive to cover for U.S. allies that did the dirty work of torturing and slaughtering to pacify key regions of Central America two decades ago. In the Iran-Contra scandal, Abrams pleaded guilty to two counts of lying to Congress, and was pardoned by President George H.W. Bush.

In his years as assistant secretary of state dealing with Latin America in the Reagan administration, as David Corn wrote in the Nation in 2001, "One Abrams specialty was massacre denial. During a 'Nightline' appearance in 1985, he was asked about reports that the US-funded Salvadoran military had slaughtered civilians at two sites the previous summer. Abrams maintained that no such events had occurred." In fact, as Corn continued, in 1993 a U.N. truth commission "examined 22,000 atrocities that occurred during the twelve-year civil war in El Salvador" and "attributed 85 percent of the abuses to the Reagan-assisted right-wing military and its death-squad allies."

Why has the notorious Central America A-team been reassembled 20 years later to oversee the pacification and supposed transfer of sovereignty in Iraq? Before the revelations of the abuses in Abu Ghraib prison, no one in the mainstream U.S. media would have dared raise -- and most would not even have dreamed of -- the possibility that behind the rhetoric of turning Iraq into a shining city on a hill for the rest of the Middle East, some U.S. policymakers and their think-tank acolytes might be prepared to unleash policies that would not be for the squeamish, to put it mildly.

No doubt it shocked the old Central America hands when the Abu Ghraib prison abuses blew up into a national political scandal that catalyzed the plummeting of President Bush's approval ratings. The well-documented torture and massacres in Central America, on a vastly greater scale, never came close to setting off a fraction of this furor. Nor did they occur after an immensely controversial war in which hundreds of Americans have died, or involve ordinary U.S. enlisted soldiers, G.I. Janes as well as G.I. Joes. And the unfortunate Maya Indians did not have al-Jazeera and other TV networks beaming their sufferings straight to the wider world.

Had Abu Ghraib never been exposed, and had Ahmed Chalabi managed to avoid finally exhausting the patience of his indulgent Pentagon protectors, he might eventually have taken over as prime minister of a supposedly democratic Iraq and imposed, to his heart's content, all the "tough but necessary" measures he advocated in his Aug. 31, 2003, Washington Post Outlook section article. Chalabi urged a crackdown: "Coalition forces need to move quickly to arrest and question thousands of people" (the names of whom his Iraqi National Congress would provide).

"Some of these steps will cause disruption to innocent people and will spawn some short-term resentment towards the coalition, but they must be taken," Chalabi wrote. Then, presumably, Ambassador Negroponte in Baghdad, backed by the National Security Council's Abrams in Washington, would have heard no evil and seen no evil.

Even now, it is probably a safe bet that Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz and others are still hoping to come up with some plausible and presentable strongman for Iraq, convinced that if he is given a free hand to do the dirty work he deems necessary, the tidal waves of Sunni and Shiite rage alike will soon be made to go away.

There is one important difference between today's Iraq and Middle East and Central America 20 years ago. It was one thing for a handful of U.S. intelligence operatives and special operations officers and troops bred to discretion and secrecy to work in the shadows with our allies then. It is quite another thing when entirely decent U.S. soldiers -- we still don't know how many -- are encouraged or ordered to carry out such abhorrent activities on a major scale themselves.

The dirty war of Abu Ghraib is out of the bottle, and Abrams and Negroponte will not be able to provide the kind of politically acceptable cover for tough measures they specialized in long ago, which the practitioners of the Central American model were confident would also pacify Iraq. Negroponte will head to Baghdad come July as an enabler without, for once, having a strongman to enable -- and without the reliable Honduran Army to do the dirty work. But those methods could only work in the shadows, not in unrelenting light. He arrives at his post in Baghdad with the whole world watching.

Shares