It's late, after 10 p.m. on a day that began almost 20 hours earlier three time zones away, and Sen. John Kerry is standing in the rain on the tarmac at Seattle's Boeing Field. He's right behind the left wing of his new campaign plane, and he's got an employee from the air charter company out there with him. Kerry is gesturing toward the fuselage of the 757, as if he's painting the plane with an imaginary brush.

The red, white and blue jetliner is already emblazoned with the words "John Kerry" and "President," and there's an array of stars shining down from the tail. But what the plane doesn't have yet is a big American flag, and Kerry wants one -- so much so that he's out here in the rain, making his exhausted aides, a battalion of Secret Service agents and a busload of reporters wait while he decides exactly where that flag should go.

It would be easy to write off Kerry's paint-job obsession as some kind of Jimmy Carter, scheduling-the-White-House-tennis-courts, control-freak episode. There may be an element of that, but that's not all of it. After shoring up his support on the antiwar left -- in recent weeks, Kerry charmed Ralph Nader, campaigned with Howard Dean and received Al Gore's public permission to tread a little lightly on Iraq -- Kerry is pushing himself hard as a tough-on-defense leader who rejects the Democrats' traditional second-fiddle role on issues of foreign policy and national defense.

"I'm not going to let the Republicans pretend that they're doing something better or have the better ability to do that," Kerry told Salon Thursday night. "I think these guys have made America less safe, and I think I have a plan to make us stronger."

The problem for Kerry, of course, is Iraq. Kerry laid out a general plan for Iraq in a speech in Missouri last month, but he has said little about how the U.S. should navigate the war since then. In the big national security speech Kerry delivered in Seattle Thursday, Iraq's future was all but an afterthought; Kerry spent a lot of time criticizing Bush for getting the U.S. -- and Iraq -- into the current predicament, but he devoted very little of his speech to what should happen next.

In one sense, it may not matter. Gore said this week that Kerry needn't be more specific about his Iraq plans: "Kerry should not tie his own hands by offering overly specific, detailed proposals concerning a situation that is rapidly changing and, unfortunately, rapidly deteriorating," Gore said. Rather, in words that invoked Watergate, the former vice president said Kerry should "preserve his, and our country's, options to retrieve our national honor as soon as this long national nightmare is over."

It's a view shared by many who support Kerry. A Kerry aide familiar with the deliberations that led to Kerry's national security address Thursday said that there was no point in Kerry repeating the plan he set forth last month. And Sandy Berger, the former national security advisor who is now advising Kerry, said that the presumptive Democratic nominee "doesn't feel the need to jump into the news cycle" and comment every time something goes wrong in Iraq.

To the extent that the Kerry audience is the Democratic base, that conclusion is probably right. While Dennis Kucinich and others on the far left have called for the U.S. to withdraw from Iraq immediately, many Democrats view that as an unlikely and unreasonable course of action, at least for now. And many more are so troubled by the Bush administration's failings in Iraq that they're ready to sign on with Kerry's plan, even if they don't know what it is.

Waiting outside a fundraiser in Seattle Wednesday night, a 20-something computer programmer hinted that Kerry hadn't been his first choice for the Democratic ticket and said he hoped to hear more from Kerry about how to improve the situation in Iraq. "But I've got to be honest with you," he said. "It doesn't matter. I mean, the guy could get up there and dance naked on the stage, and I'd still vote for him because he's so much better than the alternative."

Amy Keiter, a 47-year-old state worker from Oregon who happened to be visiting Seattle when Kerry was in town, said she too was willing to give Kerry a pass on articulating a well-defined alternative to Bush's Iraq plan. "Right now, it's such an 'anybody but Bush thing' for me," said Keiter, the mother of a 16-year-old boy who worries what the war might mean for her son. "I mean, I don't even know what Kerry's plan is to extricate us from Iraq. Does he have one?"

Oddly, it's the more conservative Democrats -- plus swing voters and Republicans thinking of crossing over -- who may need to hear more of Kerry's Iraq alternative. Beverly Weyenberg, a retiree who turned out to see Kerry in Green Bay Thursday night, saw the candidate on TV about six months ago and knew instantly that he'd be her choice. "I felt it so strongly that I wrote it down on my calendar," she says, adding that she "felt the same way about John F. Kennedy." Still, she gets a little teary when she starts to thinking about those "kids" dying in Iraq, and she wants to know Kerry's plan for bringing them home soon.

So, too, does a Republican shuttle-bus driver in Green Bay who voted for Bush in 2000 but is having second thoughts now. He can't help thinking that the war was really about oil, that Donald Rumsfeld is hiding something. He trusts Bush because he trusts Colin Powell, but with Powell on the outs he's worried. He's thinking about Kerry, he said, but he's worried that Kerry won't be able to get out of Iraq, either.

But even if Kerry had done a better job getting his plan before the public, it's hard to imagine that it would have provided much comfort for those seeking a specific exit plan for the U.S. in Iraq. Kerry wants more international involvement, more help from NATO, more humility from the president and the appointment of a U.N. high commissioner.

In his Seattle speech Thursday, Kerry called on Bush to press hard for international help at the upcoming G-8 summit in Sea Island, Ga., and the NATO summit in Istanbul. "There will be speeches and handshakes and ceremonies," Kerry said of the summits. "But will our allies promise to send more troops to Iraq? Will they pledge a real effort to aid the transformation of the Middle East? That is what we need. But the day is short, and the situation in Iraq is grim."

With nothing more specific to say, Kerry will be left trying to persuade voters that he is a tough leader, the kind of guy who promises, as he did in Seattle this week, to "destroy" terrorists and respond to attacks with "overwhelming and devastating force."

He will reassure swing voters and others wary of wimpy Democrats with rhetoric that wraps his policy positions in respect for the military; in speeches, Kerry focuses less on the Bush administration's disregard for the U.N. and much more on the way it "disrespected" the military officers who tried to warn it off of the Iraq folly.

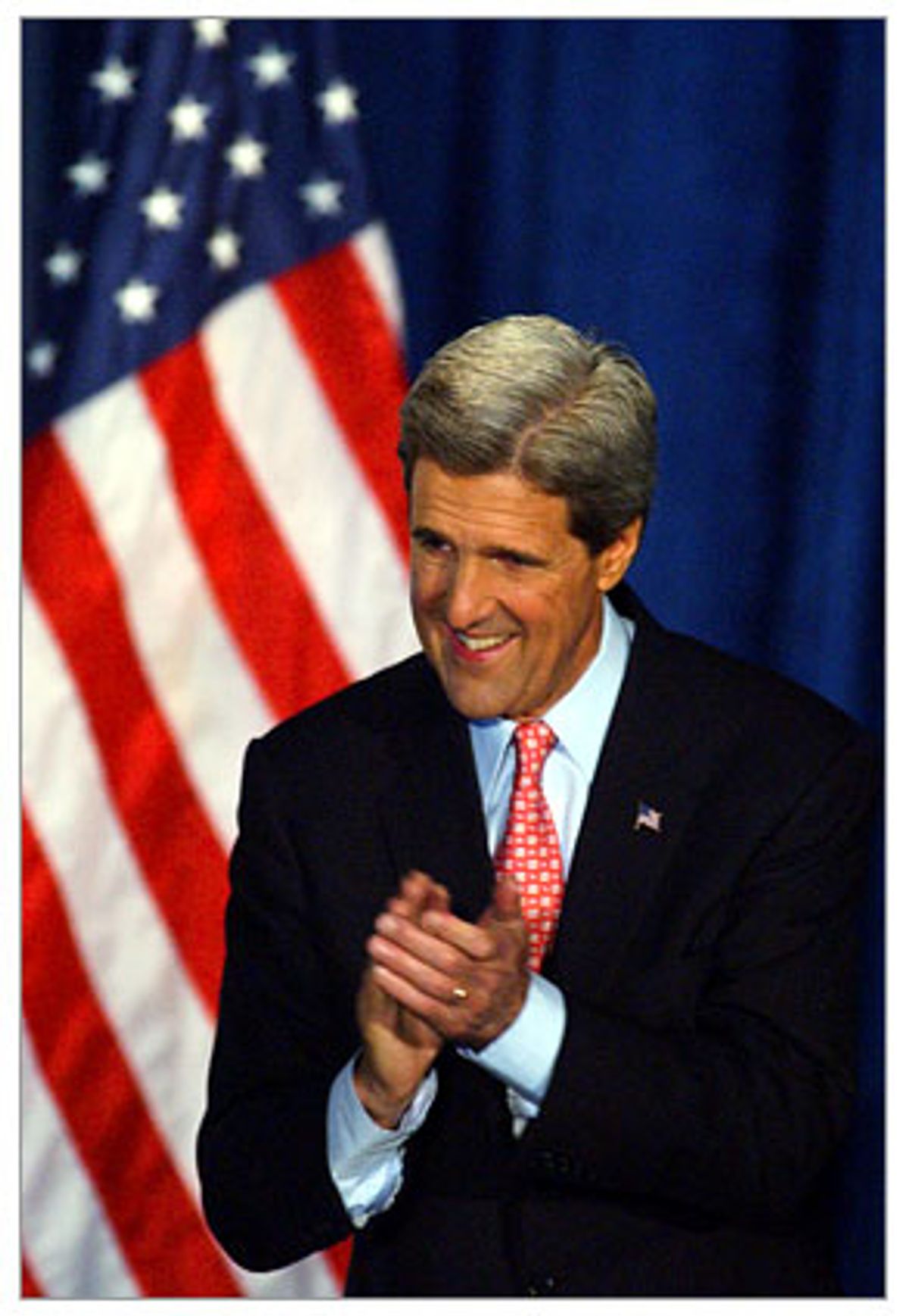

Kerry will run a campaign that positions him strongly as a military man, hoping to attract Republicans fed up with Bush's misadventures. That means that one of the swift-boat veterans who served with Kerry in Vietnam travels with him now from state to state. It means veterans frequently get a special seating area near the front of the stage. It means that events often begin with the Pledge of Allegiance. And it means that American flags dot Kerry's necktie, hover over him when he speaks and will soon grace his plane when he flies.

For liberal Democrats, it all takes a little getting used to. Conditioned over the last four years to associate the flag with Bush-Cheney bumper stickers on SUVs and the Pledge with the folks who shout out the "under God" clause, Democrats at Kerry events -- even those who support his approach to Iraq -- may find themselves in an uncomfortable embrace with the trappings of patriotism.

As a veteran who fought in Vietnam and then against it, Kerry gives them cover. In Seattle Thursday, Kerry reminded the veterans and graduate students invited to hear his national security speech that "patriotism doesn't belong to one party or one president." Thursday night in Green Bay, Wis., he told a crowd of Democratic partisans that the flag is a "symbol of our strength, and our strength comes from our ability to speak out and make America stronger."

While Kerry could probably be stronger if he weren't constrained by his own record -- and the lack of easy answers -- on Iraq, as he traveled through the Northwest and back again this week, it was hard not to feel the momentum building behind him anyway. Although some polls still show Kerry and Bush running neck-and-neck, the latest CBS poll shows Kerry leading by 8 points. Perhaps more encouraging for Kerry is a new poll showing rising favorable impressions among voters where it matters, in 20 key battleground states. And on Friday, his increasingly confident campaign announced that Kerry would even challenge the president in Republican-leaning Virginia, a state where Bush beat Gore in 2000 by a solid 8 points.

Democrats have fretted that Kerry hasn't defined himself yet, but that process is now in high gear. With the primary season behind him, Kerry suddenly begins to come off not as one of eight guys on a stage with Al Sharpton, but rather as someone who looks and acts like a president. He's so in demand by the TV news that his campaign staffers run him through five or six or seven or eight satellite interviews a day, one after another in rapid succession, with just enough time in between for a press aide to tell Kerry which city is next and remind him of a few salient facts about it.

And when Kerry rolls into a town -- his plane landing at the airport, his motorcade racing through streets, waves of Secret Service agents sweeping through the restaurants where he eats and the hotels where he stays -- it looks to all the world like a presidential visit. In Portland Tuesday evening, people spilled out of bars to wave and cheer as Kerry's motorcade rumbled past. In downtown Seattle Wednesday morning, thousands of supporters lined the streets in the rain for a chance to see the candidate and to hear him speak. And in Green Bay Thursday night, the Kerry campaign rolled into a roaring, confetti-coated rally overflowing with all the raucous joy of a Packers victory party.

In an arena across the way from the Packers' legendary Lambeau Field, a certain green-and-gold color theme was probably inevitable. But when the local newspaper ran a photo of Kerry on the front page Friday morning, the campaign had what it wanted: a shot of the candidate, veterans arrayed behind him, and a big American flag overhead.

Shares